Fundamentals

You feel it as a subtle shift in your body’s internal landscape. The energy that once carried you through the day now seems to wane, a persistent fatigue settles in, and perhaps you notice changes in your body composition that feel disconnected from your daily habits.

These experiences are valid, and they often point toward a fundamental process within your endocrine system ∞ a change in how your cells listen to the hormone insulin. This is the starting point for understanding your own biology, a journey toward reclaiming vitality by recalibrating your body’s intricate communication network.

The question of how long it takes for lifestyle changes to improve insulin sensitivity is a deeply personal one, as the timeline is written in the language of your unique physiology. The process is one of cellular reawakening.

Your cells, having become accustomed to a high volume of insulin ∞ a state known as insulin resistance ∞ begin to regain their ability to respond to its signals. This is not a simple on-off switch but a gradual process of restoring a delicate conversation between the hormone and its receptors. The initial changes can be surprisingly swift, with measurable improvements in how your body manages blood sugar occurring within days of implementing consistent, targeted lifestyle modifications.

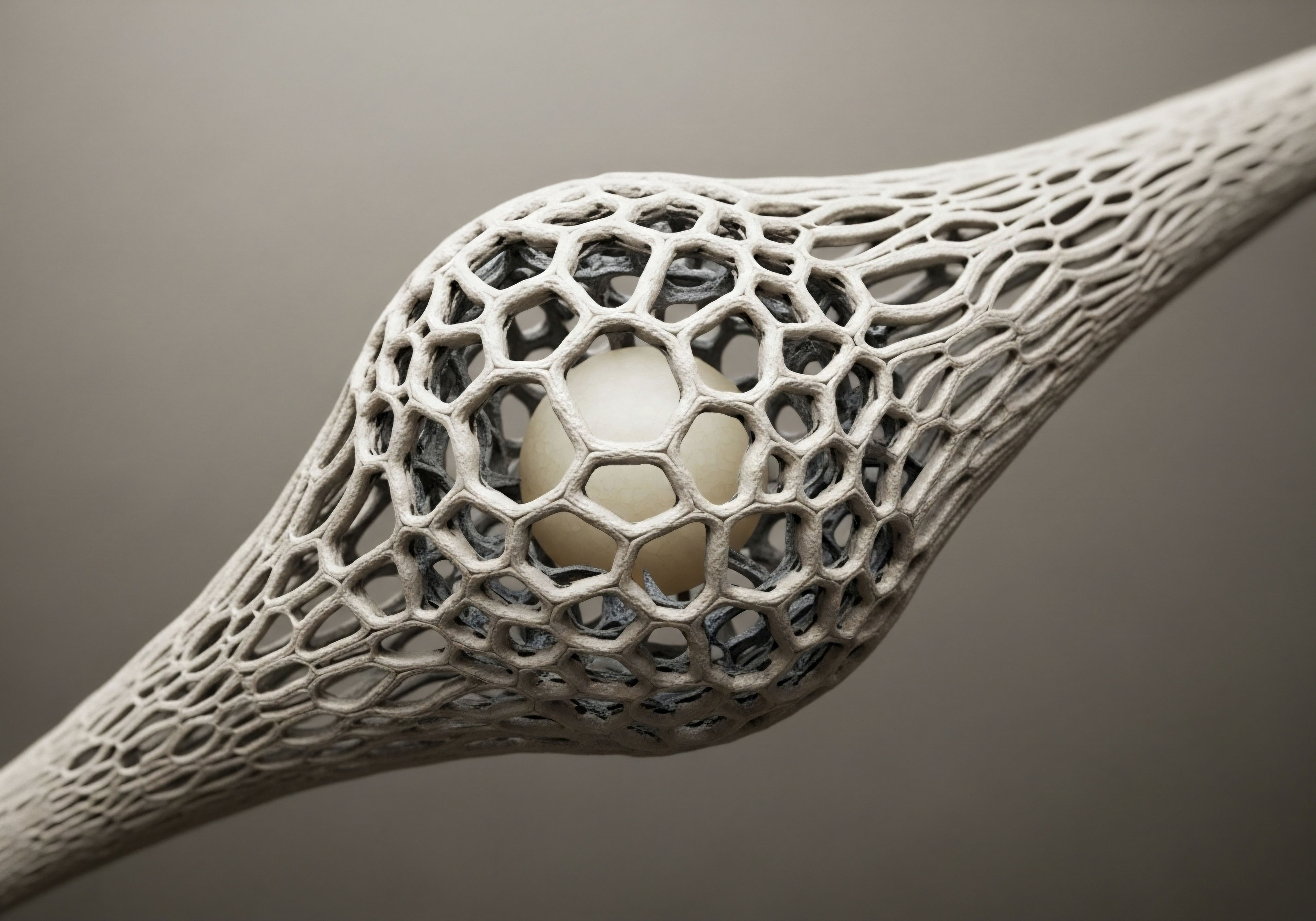

Think of your cells as having tiny doorways, and insulin as the key that unlocks them to allow glucose, your body’s primary fuel, to enter. When insulin resistance develops, these doorways become less responsive to the key. Lifestyle changes, particularly in nutrition and physical activity, act as a master locksmith, cleaning the locks and recutting the keys.

Within the first two weeks of consistent effort, the most significant initial improvements are often observed. This is because your body begins to deplete stored glucose and your muscles, when active, can take up glucose without relying as heavily on insulin. This provides immediate relief to the pancreas, which has been working overtime to produce more and more insulin to compensate for the resistance.

As you continue these new habits, the adaptations become more profound. Over a period of one to three months, your body initiates more substantial changes. The fat cells, particularly those around your organs, may begin to shrink, reducing the inflammatory signals that interfere with insulin’s function.

Your liver becomes more efficient at managing glucose production, and the number and sensitivity of insulin receptors on your cells can increase. This period is when the new lifestyle patterns start to feel less like a temporary intervention and more like a new, sustainable way of being.

Your energy levels may stabilize, mental clarity can improve, and the physical changes become more apparent. The journey is one of continuous adaptation, with your body responding to the consistent signals of nourishment and movement you provide.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the initial, rapid improvements in insulin sensitivity requires a deeper understanding of the physiological mechanisms at play. The timeline for sustained improvement is governed by the interplay of several biological systems, each responding to lifestyle interventions at a different pace.

While the first few weeks are characterized by functional changes in glucose uptake, the period from three to six months is where we see more significant structural and systemic adaptations. This phase is about reinforcing the initial gains and embedding them into your body’s long-term operational patterns.

The Role of Adipose Tissue Remodeling

One of the central processes in this intermediate phase is the remodeling of adipose tissue, or body fat. Adipose tissue is an active endocrine organ, secreting hormones and inflammatory molecules that directly impact insulin sensitivity.

When you consistently incorporate lifestyle changes, particularly those that lead to a modest reduction in weight, you are not just losing mass; you are changing the behavior of your fat cells. Visceral fat, the fat stored around your internal organs, is particularly detrimental to insulin sensitivity.

As this fat is reduced, the production of inflammatory cytokines decreases, and the secretion of adiponectin, a hormone that improves insulin sensitivity, increases. This process of adipose tissue remodeling is a gradual one, with significant changes occurring over several months of consistent effort.

Sustained lifestyle changes over three to six months can lead to significant remodeling of adipose tissue, reducing inflammation and improving insulin sensitivity.

Cellular Mechanisms of Improved Insulin Signaling

Within the cells themselves, a cascade of events is unfolding. Chronic insulin resistance leads to a downregulation of insulin receptors and a disruption of the downstream signaling pathways. Consistent exercise and a nutrient-dense diet work to reverse these changes. Here is a breakdown of the key cellular adaptations:

- Increased GLUT4 Translocation Physical activity, especially a combination of resistance training and cardiovascular exercise, stimulates the movement of glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) to the cell membrane. This allows glucose to enter the cell from the bloodstream, a process that can occur independently of insulin. This effect is immediate and contributes to the rapid improvements seen in the first few weeks.

- Enhanced Insulin Receptor Sensitivity Over time, as the constant demand for high levels of insulin decreases, the insulin receptors on your cells can regain their sensitivity. This is a process of cellular recalibration, where the cells become more responsive to smaller amounts of insulin.

- Reduced Lipotoxicity When fat accumulates in non-adipose tissues like the liver and muscles, a condition known as lipotoxicity, it can interfere with insulin signaling. Lifestyle changes that promote fat loss help to clear these lipid deposits, allowing for more efficient glucose metabolism.

The Hormonal Axis and Insulin Sensitivity

The endocrine system is a web of interconnected pathways, and insulin sensitivity is influenced by a host of other hormones. For men, testosterone plays a role in maintaining lean muscle mass and promoting healthy fat distribution, both of which are beneficial for insulin sensitivity. In women, the fluctuations of estrogen and progesterone during the perimenopausal and post-menopausal periods can impact insulin resistance. Hormonal optimization protocols, when clinically indicated, can support the improvements in insulin sensitivity achieved through lifestyle changes.

The table below outlines the general timeline for improvements in insulin sensitivity with consistent lifestyle modifications:

| Timeframe | Physiological Changes | Expected Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| 1-2 Weeks | Increased muscle glucose uptake, reduced liver glucose output. | More stable blood sugar levels, reduced post-meal energy crashes. |

| 1-3 Months | Initial reduction in visceral fat, improved insulin receptor function. | Noticeable improvements in energy, modest weight loss. |

| 3-6 Months | Significant adipose tissue remodeling, reduced inflammation. | Sustained improvements in lab markers (fasting insulin, HbA1c), improved body composition. |

| 6+ Months | Long-term cellular adaptations, establishment of new metabolic baseline. | Maintenance of insulin sensitivity, reduced risk of chronic disease. |

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of the timeline for improving insulin sensitivity necessitates a move beyond generalized observations and into the realm of molecular biology and endocrinology. The process is a multi-system phenomenon, with distinct yet overlapping phases of adaptation occurring in skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, and the liver. The rate and extent of these adaptations are dictated by the specific nature of the lifestyle interventions, as well as the individual’s genetic predispositions and baseline metabolic health.

Immediate and Short Term Adaptations in Skeletal Muscle

Skeletal muscle is the primary site for insulin-mediated glucose disposal, accounting for approximately 80% of glucose uptake in the postprandial state. The most immediate improvements in insulin sensitivity are observed here. A single bout of exercise can increase glucose uptake for up to 48 hours, a phenomenon mediated by the insulin-independent translocation of GLUT4 to the cell surface.

This is driven by the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), an energy sensor within the cell. With consistent training over several weeks, there is an increase in the expression of key proteins involved in the insulin signaling cascade, including the insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) and Akt, also known as protein kinase B. These adaptations enhance the cell’s ability to respond to insulin, leading to more efficient glucose uptake and storage as glycogen.

How Does Adipose Tissue Inflammation Affect Insulin Signaling?

The link between excess adiposity and insulin resistance is well-established, with chronic, low-grade inflammation being a key mechanistic link. Hypertrophied adipocytes in visceral fat depots release a variety of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6).

These cytokines can directly impair insulin signaling in peripheral tissues through the activation of inflammatory pathways, such as the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and IκB kinase (IKK) pathways. These pathways can phosphorylate IRS-1 at serine residues, which inhibits its normal function and disrupts the downstream insulin signaling cascade.

Lifestyle interventions that lead to a reduction in visceral fat mass, a process that typically takes several months, result in a decrease in the circulating levels of these inflammatory cytokines. This reduction in inflammatory tone is a critical step in restoring systemic insulin sensitivity.

Reducing visceral adipose tissue through sustained lifestyle changes can decrease systemic inflammation, a key driver of insulin resistance.

Hepatic Insulin Resistance and Its Reversal

The liver plays a central role in maintaining glucose homeostasis by regulating endogenous glucose production. In a state of insulin resistance, the liver fails to suppress gluconeogenesis, the production of glucose from non-carbohydrate sources, leading to elevated fasting blood glucose levels.

This is often associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), where the accumulation of ectopic fat in the liver impairs insulin signaling. Lifestyle interventions, particularly dietary modifications that reduce the intake of refined carbohydrates and saturated fats, can have a profound impact on hepatic insulin sensitivity.

Studies have shown that a reduction in liver fat can be achieved within a matter of weeks with a calorie-controlled diet, leading to a rapid improvement in the liver’s ability to respond to insulin. The table below details the impact of specific lifestyle interventions on key metabolic markers.

| Intervention | Primary Mechanism | Timeline for Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| Resistance Training | Increased muscle mass, enhanced GLUT4 translocation. | 2-4 weeks for initial changes, 3-6 months for significant muscle hypertrophy. |

| Cardiovascular Exercise | Improved mitochondrial function, increased capillary density in muscle. | 4-8 weeks for measurable improvements in VO2 max and mitochondrial biogenesis. |

| Caloric Deficit | Reduction in visceral and hepatic fat. | 2-12 weeks for significant reduction in liver fat, 3-6 months for substantial visceral fat loss. |

| Reduced Sugar Intake | Decreased de novo lipogenesis in the liver. | 1-2 weeks for reduced hepatic fat synthesis. |

The long-term restoration of insulin sensitivity is a complex process that involves the coordinated adaptation of multiple organ systems. While the initial improvements can be rapid, the more profound and lasting changes are the result of consistent, sustained lifestyle modifications over a period of several months to a year. These changes are not merely a reversal of the disease process but a fundamental rebuilding of metabolic health at the cellular and systemic levels.

References

- Malin, S. K. & Kullman, E. L. (2020). The role of exercise in the treatment of insulin resistance. Current Diabetes Reports, 20 (9), 1-9.

- Petersen, M. C. & Shulman, G. I. (2018). Mechanisms of insulin action and insulin resistance. Physiological reviews, 98 (4), 2133-2223.

- Goodpaster, B. H. & Sparks, L. M. (2017). Metabolic flexibility in health and disease. Cell metabolism, 25 (5), 1027-1036.

- Kahn, S. E. Hull, R. L. & Utzschneider, K. M. (2006). Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature, 444 (7121), 840-846.

- Toledo, F. G. & Goodpaster, B. H. (2013). The role of weight loss and exercise in correcting skeletal muscle mitochondrial dysfunction in obesity. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care, 16 (6), 666-672.

Reflection

The information presented here offers a clinical roadmap, a scientific explanation for the changes you may be feeling within your own body. This knowledge is a powerful tool, yet it is only the first step. Your personal health journey is unique, a complex interplay of your genetics, your history, and your daily life.

The timelines and mechanisms discussed provide a framework, but the true path to reclaiming your vitality is one of self-discovery and personalized action. Consider this a starting point for a deeper conversation with your own body, a conversation that may be guided and informed by clinical expertise but is ultimately yours to lead. The potential for profound change lies within your daily choices, and the journey toward metabolic health is one of continuous learning and adaptation.

Glossary

endocrine system

insulin sensitivity

lifestyle changes

insulin resistance

lifestyle interventions

glucose uptake

adipose tissue

visceral fat

adipose tissue remodeling

glut4 translocation

cellular recalibration

glucose metabolism

insulin signaling

metabolic health