Fundamentals

You feel it before you can name it. A subtle shift in your internal rhythm, a change in energy, or a new pattern in your monthly cycle. This experience, your lived reality, is the most important data point you possess. It is the first signal that the intricate communication network within your body is adapting.

The question of how long it takes for lifestyle changes to affect estrogen levels begins not with a stopwatch, but with this recognition of your own biological feedback. Your body is constantly speaking through the language of hormones, and learning to listen is the foundational step in guiding its conversation toward health and vitality.

Estrogen is a primary dialect in this internal language. It is a family of steroid hormones, with the three most significant members being estrone (E1), estradiol (E2), and estriol (E3). Estradiol is the most potent form, profoundly influencing the reproductive system, bone density, cardiovascular health, and even cognitive function.

These molecules are chemical messengers, produced primarily in the ovaries under the direction of a sophisticated command and control system known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. Think of the hypothalamus in your brain as the mission commander, sending timed signals to the pituitary gland, which in turn directs the ovaries to produce estrogen in a rhythmic, cyclical pattern. This elegant system is the source of the menstrual cycle, a monthly testament to its precision.

The body’s hormonal balance is a dynamic system of communication, where lifestyle choices act as direct inputs influencing estrogen levels.

The Power of Lifestyle as Information

Your daily choices are powerful inputs into this HPG axis. The food you eat, the way you move your body, the quality of your sleep, and your management of stress are all pieces of information that your endocrine system receives and processes.

These are not merely suggestions; they are direct instructions that can modulate the production, circulation, and metabolism of estrogen. A diet high in processed foods and refined sugars sends a very different signal than one rich in fiber and phytonutrients. Similarly, a sedentary day provides different instructions to your cells than a day that includes purposeful movement.

Understanding this principle is empowering because it reframes “healthy habits” as acts of biological communication. You are actively participating in the regulation of your own physiology. The timeline for these changes to manifest is layered. Some effects are immediate, while others require sustained consistency to recalibrate the entire system.

- Weeks 1-4 You may first notice improvements in non-hormonal markers that are influenced by estrogen. This includes more stable energy levels, improved mood, and better sleep quality. These are often the result of stabilized blood sugar and reduced inflammation, which are precursors to hormonal shifts.

- Months 1-3 With consistent changes, more direct hormonal effects begin to appear. For women with menstrual cycles, this could manifest as more regular timing, a reduction in premenstrual symptoms, or changes in flow. These are signs that the HPG axis is responding to the new, healthier inputs. Measurable changes in blood markers like Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) may become apparent in lab testing.

- Months 3+ Lasting changes in body composition, such as a reduction in visceral fat, further reinforce hormonal balance. At this stage, the new lifestyle patterns have helped to establish a more resilient and stable hormonal environment. For women in perimenopause, consistent lifestyle efforts can help buffer the natural fluctuations of this transition, potentially lessening the severity of symptoms like hot flashes.

How Does the Body Adjust to New Estrogen Levels?

The body’s adaptation to new estrogen levels is a gradual process of recalibration. When lifestyle changes begin to influence estrogen production and metabolism, cellular receptors and feedback loops adjust accordingly. For instance, if changes in diet and exercise lead to a healthier body composition, the amount of estrogen produced in fat tissue via aromatization decreases.

The body then adapts to this new, lower baseline. This process involves adjustments within the HPG axis, where the hypothalamus and pituitary gland modify their signaling to align with the new state of the body. It is a testament to the body’s inherent drive to maintain equilibrium, a state known as homeostasis.

Intermediate

To appreciate the timeline of hormonal change, we must look deeper into the biochemical machinery that governs estrogen. Your lifestyle choices are the raw materials and operational commands for this machinery. The speed and efficacy of hormonal recalibration depend on how effectively these new inputs modify three core processes ∞ estrogen production, circulation, and detoxification.

The initial feelings of wellness after a few weeks of change are real and significant; they are the surface ripples of a deeper current of metabolic and endocrine adjustment that builds over months.

Dietary Architecture and Estrogen Metabolism

Food is a primary modulator of estrogen levels, influencing the hormone from its creation to its elimination. This biochemical influence is precise and multifaceted.

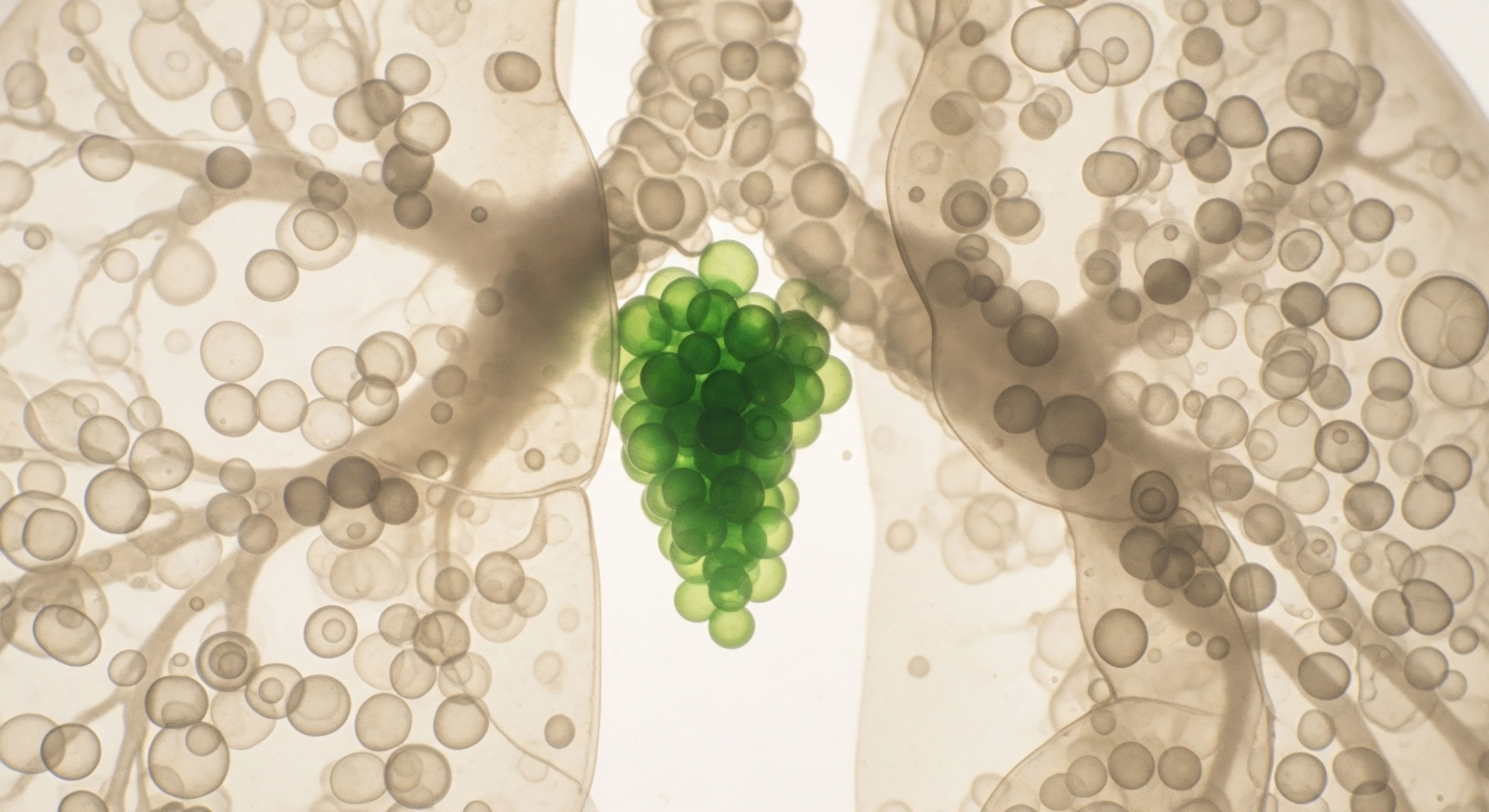

The Gut Estrobolome

Your gut contains a specific collection of bacteria, collectively termed the “estrobolome,” that plays a critical role in regulating circulating estrogen. After the liver processes estrogen for elimination, it is sent to the gut. Certain gut bacteria produce an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase, which can “reactivate” this estrogen, allowing it to re-enter circulation.

A diet low in fiber and high in processed foods can alter the estrobolome, leading to increased beta-glucuronidase activity and, consequently, higher levels of circulating estrogen. Conversely, a diet rich in soluble and insoluble fiber from vegetables, fruits, and legumes supports a healthy microbiome that promotes the efficient excretion of estrogen.

This dietary shift can begin to alter the gut microbiome within days, but establishing a new, stable estrobolome that consistently influences hormone levels can take several months of dedicated eating patterns.

Adipose Tissue the Other Endocrine Gland

Body fat, particularly visceral fat around the organs, is a significant site of estrogen production in both men and women. An enzyme called aromatase, which is abundant in fat cells, converts androgens (like testosterone) into estrogen. Higher levels of body fat create a larger factory for this conversion, contributing to a state of estrogen excess relative to other hormones like progesterone.

Lifestyle changes that promote fat loss, especially a combination of strength training and metabolically healthy nutrition, directly reduce the body’s aromatase activity. This is a slower adaptation. While metabolic markers like insulin sensitivity can improve within weeks, significant changes in body composition typically require two to six months of consistent effort. This reduction in peripheral estrogen production is a key mechanism for restoring balance, particularly during perimenopause and for men seeking to optimize their testosterone-to-estrogen ratio.

Changes in body composition through diet and exercise directly impact hormonal balance by reducing the peripheral production of estrogen in fat tissue.

The following table outlines a more detailed timeline of expected physiological responses to sustained lifestyle interventions aimed at modulating estrogen.

| Timeframe | Physiological Response & Mechanisms | Observable Experience |

|---|---|---|

| Week 1-4 | Improved insulin sensitivity from reduced sugar intake and increased movement. Decreased acute inflammation. Initial shifts in the gut microbiome composition. | More stable energy, reduced cravings, improved mood, better sleep, less bloating. |

| Month 1-3 | Increased production of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) in response to exercise and a lower-glycemic diet. Measurable changes in inflammatory markers (e.g. C-reactive protein). More stable estrobolome function. | More regular menstrual cycles, reduced PMS, clearer skin. For men, potential reduction in estrogen-related side effects. |

| Month 3-6 | Significant changes in body composition (reduced adipose tissue). Reduced aromatase activity. Improved cortisol rhythm from better sleep and stress management. | Sustained improvements in cycle regularity, reduced menopausal symptoms (e.g. hot flashes), and optimized metabolic health. |

| Month 6+ | Establishment of a new homeostatic set point for the HPG axis. Enhanced resilience of the endocrine system to stressors. Maintained bone density support. | A new baseline of well-being and predictable physiological function. Long-term risk reduction for hormone-sensitive conditions. |

Exercise as an Endocrine Signal

Physical activity is a potent hormonal regulator. The type, intensity, and consistency of exercise send distinct signals to the endocrine system.

- Strength Training Building lean muscle mass increases the body’s metabolic rate and improves insulin sensitivity. This helps manage body composition, thereby reducing the aromatase activity discussed earlier. These effects build progressively over months of consistent training.

- High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) Short bursts of intense effort have been shown to improve how efficiently the body uses insulin and can positively influence SHBG levels. Changes can be seen within a few months of incorporating HIIT 1-3 times per week.

- Consistent Moderate Activity Activities like brisk walking help regulate the stress hormone cortisol. Chronically elevated cortisol can suppress the HPG axis, disrupting the regular production of estrogen. Daily moderate exercise helps to buffer this stress response, with benefits to sleep and mood often felt within weeks.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of the timeline for hormonal change requires a systems-biology perspective, viewing the endocrine system as an integrated network where the gut microbiome, circadian rhythms, and metabolic health are deeply intertwined.

The question evolves from a simple “how long” to a more precise inquiry ∞ “What is the cascade of events, from cellular signaling to systemic hormonal expression, initiated by lifestyle interventions, and what is its temporal progression?” The most profound and durable changes to estrogen levels are achieved by modulating the intricate relationship between the gut-liver axis and the master clock of the hypothalamus.

The Estrobolome and Hepatic Conjugation a Primary Control Point

The regulation of estrogen is not solely dependent on its production (biosynthesis) but is heavily influenced by its metabolism and elimination. The liver conjugates, or packages, estrogens for excretion via a process called glucuronidation. These conjugated estrogens are then transported to the bile and released into the intestinal tract. Here, the estrobolome ∞ the aggregate of enteric bacterial genes capable of metabolizing estrogens ∞ becomes the critical gatekeeper.

Specific bacterial species produce the enzyme β-glucuronidase. This enzyme deconjugates estrogen, severing the package applied by the liver and releasing free, biologically active estrogen back into circulation (enterohepatic recirculation). A dysbiotic microbiome, often characterized by low phylogenetic diversity and an over-representation of Firmicutes, can exhibit high β-glucuronidase activity.

This leads to a greater recirculation of estrogen, elevating the body’s total exposure. Lifestyle interventions targeting the microbiome, such as the introduction of high-fiber foods (prebiotics) and fermented foods (probiotics), can begin to shift the microbial population and its enzymatic output within 72 hours. However, a stable and resilient shift in the estrobolome’s functional capacity, sufficient to durably alter serum estrogen levels, is a process that unfolds over 3 to 6 months of consistent dietary architecture.

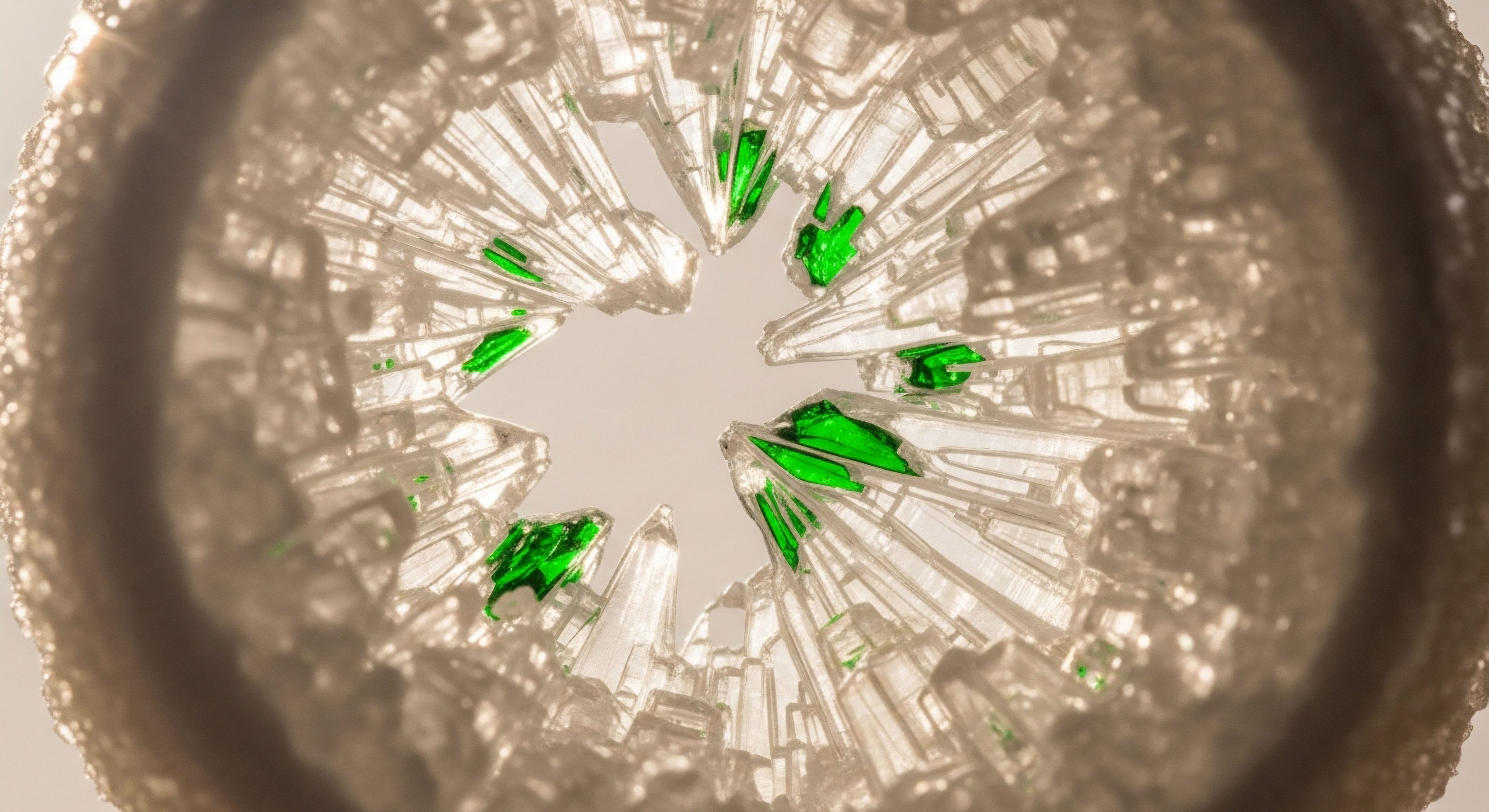

What Is the Role of Circadian Biology in Hormonal Regulation?

The HPG axis is fundamentally governed by circadian biology. The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus, the body’s master clock, dictates the pulsatile release of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH). This GnRH pulse frequency and amplitude, in turn, governs the pituitary’s release of Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH), which ultimately control ovarian estrogen synthesis.

Modern lifestyle patterns, such as exposure to blue light at night, erratic sleep schedules, and late-night eating, create a state of circadian disruption. This desynchronizes the SCN’s master clock from peripheral clocks in organs like the liver and ovaries. The result is a chaotic GnRH signal, leading to irregular or suboptimal estrogen production. Correcting this requires more than just adequate sleep duration; it demands circadian alignment.

The following interventions are key:

- Morning Light Exposure Anchoring the circadian rhythm by exposing the eyes to natural sunlight within the first hour of waking.

- Time-Restricted Feeding Aligning the eating window with the daylight hours, which supports the liver’s metabolic clock and improves insulin sensitivity, a key factor in hormonal health.

- Blue Light Mitigation Ceasing the use of screens and bright overhead lights 2-3 hours before bedtime to allow for the natural rise of melatonin, which has a protective role for the ovaries.

The initial effects of circadian realignment, such as improved sleep quality and reduced cortisol, can be felt within one to two weeks. The recalibration of the HPG axis, however, follows a longer trajectory. Restoring a regular, robust GnRH pulse generator can take two to four menstrual cycles (approximately 2-4 months) of rigorous circadian hygiene.

The interplay between the gut’s estrobolome and the brain’s circadian clock forms a powerful regulatory axis over estrogen levels.

The table below details specific interventions and their impact on measurable biomarkers related to estrogen metabolism, drawing from clinical research.

| Intervention | Target Mechanism | Key Biomarkers Affected | Approximate Timeline for Biomarker Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Fiber Diet (35g+/day) | Modulation of the estrobolome; reduction of β-glucuronidase activity. | Urinary/fecal estrogen metabolites; serum estrogen levels. | 2-4 months for stable change. |

| Cruciferous Vegetable Intake | Supports Phase I & II liver detoxification pathways (e.g. via Indole-3-carbinol). | Ratio of 2-hydroxyestrone to 16-alpha-hydroxyestrone in urine. | 1-3 months. |

| Consistent Strength Training | Increased lean muscle mass; improved insulin sensitivity; reduced aromatase substrate. | Serum SHBG; HOMA-IR; body composition. | 3-6 months for significant shifts. |

| Strict Circadian Hygiene | Synchronization of the SCN and peripheral clocks; optimized GnRH pulsatility. | Salivary cortisol curve; serum LH/FSH; melatonin onset. | 1-3 months for hormonal rhythm stabilization. |

The Systemic Impact on Clinical Protocols

This deep understanding of the gut-brain-hormone axis has profound implications for clinical practice. For individuals considering or undergoing hormonal replacement therapy (HRT), optimizing these foundational lifestyle-driven pathways is a prerequisite for success. Initiating HRT in the context of a dysbiotic gut, high inflammation, and circadian disruption means the exogenous hormones are entering a chaotic system.

This can lead to suboptimal outcomes and a greater need for dose adjustments or ancillary medications like aromatase inhibitors. By first dedicating three to six months to targeted lifestyle interventions, a patient can create a stable physiological canvas upon which hormonal therapies can act more predictably and effectively, often allowing for lower, more physiological dosing to achieve the desired clinical effect.

References

- Cleveland Clinic. “Estrogen ∞ Hormone, Function, Levels & Imbalances.” Cleveland Clinic, 8 Feb. 2022.

- Christmas, Monica. “Why am I gaining weight so fast during menopause? And will hormone therapy help?” UChicago Medicine, 25 Apr. 2023.

- Rutledge, Brandon, et al. “Estradiol Replacement Timing and Obesogenic Diet Effects on Body Composition and Metabolism in Postmenopausal Macaques.” Endocrinology, vol. 160, no. 4, 1 Apr. 2019, pp. 915-927.

- Malin, Steven K. et al. “Timing of Meals and Exercise Affects Hormonal Control of Glucoregulation, Insulin Resistance, Substrate Metabolism, and Gastrointestinal Hormones, but Has Little Effect on Appetite in Postmenopausal Women.” Nutrients, vol. 13, no. 12, 1 Dec. 2021, p. 4348.

- WebMD. “Menopause ∞ When It Begins, Symptoms, Stages, Treatment.” WebMD, 23 Nov. 2024.

- Baker, J.M. et al. “Estrogen-gut microbiome axis ∞ Physiological and clinical implications.” Maturitas, vol. 103, 2017, pp. 45-53.

- Touvier, M. et al. “Dietary fiber and postmenopausal breast cancer risk in the SU.VI.MAX cohort.” American Journal of Epidemiology, vol. 165, no. 5, 2007, pp. 524-32.

- McTiernan, A. et al. “Relation of diet and physical activity to inflammatory markers in postmenopausal women.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 83, no. 5, 2006, pp. 1189-97.

Reflection

The information presented here offers a map of the biological terrain, detailing how the paths of diet, movement, and rest lead to the destination of hormonal balance. This knowledge is a powerful tool, shifting your perspective from being a passenger in your own body to becoming an active navigator of your health.

The timelines and mechanisms provide a framework, yet your personal journey is unique. Your body’s responses, your feelings of well-being, and your symptomatic shifts are the most important feedback. This process is one of self-discovery, an opportunity to rebuild the connection between your choices and your physiological state.

Consider this knowledge the beginning of a new dialogue with your body, one where you can listen with understanding and respond with intention, steering yourself toward a future of sustained vitality.

Glossary

lifestyle changes

estrogen levels

endocrine system

hpg axis

sex hormone-binding globulin

body composition

hormonal balance

estrogen production

estrobolome

the estrobolome

insulin sensitivity

aromatase activity

lifestyle interventions

circadian rhythm