Fundamentals

Your personal health journey is a process of learning the unique language of your own body. When you experience shifts in energy, mood, or metabolism, it is your system communicating its internal state. Understanding the conversation between different hormonal pathways is fundamental to interpreting these signals.

The relationship between estrogen therapy and thyroid function is a primary example of this intricate biological dialogue. Many individuals notice that initiating a hormonal protocol coincides with unexpected changes in their sense of well-being, and this experience points directly to the interconnectedness of our endocrine architecture.

The way your body processes estrogen is entirely dependent on the method of delivery. This distinction is central to understanding its downstream effects on other hormonal systems, particularly the thyroid. Your thyroid gland acts as the primary regulator of your body’s metabolic rate, influencing everything from body temperature to heart rate to the speed at which you burn calories. It achieves this by producing hormones, principally thyroxine (T4), which travel through the bloodstream to act on cells throughout the body.

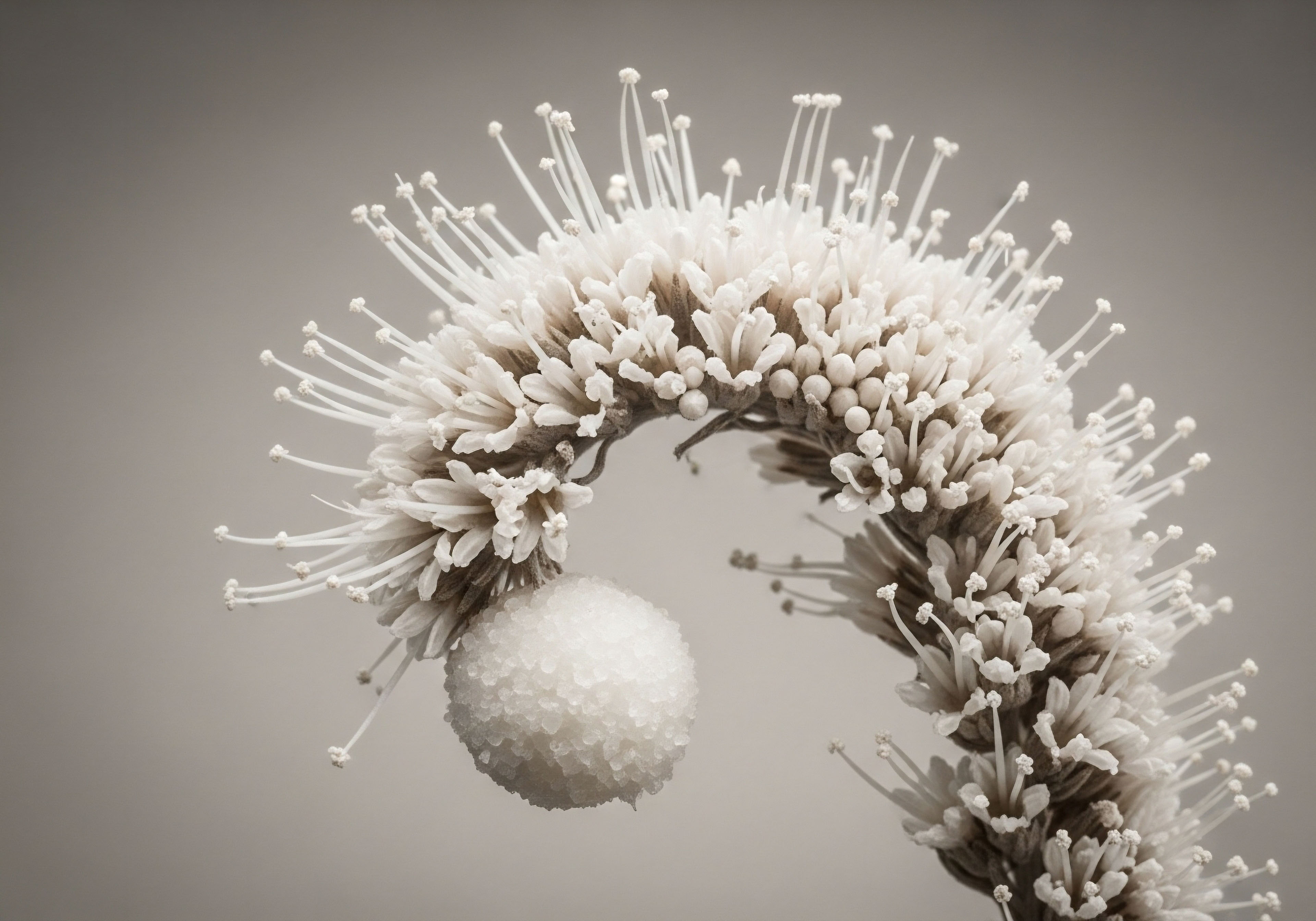

Thyroid hormones must be unbound and free in the bloodstream to be biologically active and regulate metabolism.

Thyroid Hormones Free and Bound

The concept of “free” versus “bound” hormones is essential. Think of the bloodstream as a transport system. Thyroid hormones are the passengers, but they cannot travel alone. They are escorted by specific proteins, the most important of which is Thyroxine-Binding Globulin (TBG).

When a thyroid hormone molecule is attached to TBG, it is “bound” and inactive, safely in transit. For the hormone to perform its function, it must be released from TBG and become “free.” Only this free hormone can enter cells and exert its metabolic effects. Your body maintains a careful equilibrium between bound and free thyroid hormone to ensure a steady, consistent supply of metabolic messaging.

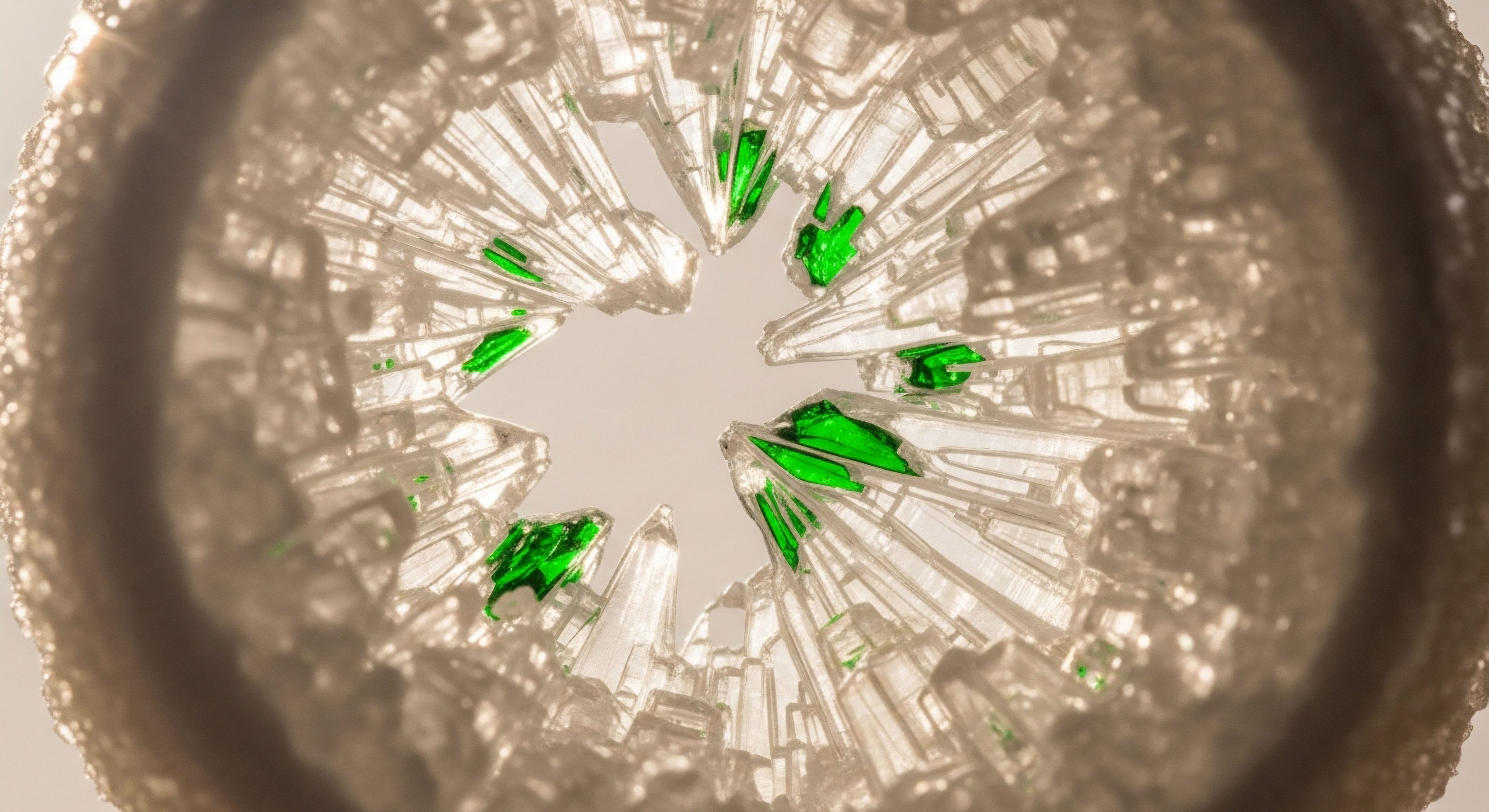

The Liver’s Role as a Processing Hub

The route a hormone takes into your body determines its interaction with the liver. When you take a medication orally, it is absorbed through the digestive tract and travels directly to the liver for processing before it ever enters general circulation. This is known as the hepatic first-pass effect.

The liver acts as a sophisticated biochemical checkpoint, metabolizing substances and, in the case of oral estrogen, responding to its presence by altering the production of various proteins. Transdermal estrogen, delivered through the skin via a patch or gel, enters the bloodstream directly. This route bypasses the initial, high-concentration exposure to the liver, leading to a profoundly different systemic outcome.

Intermediate

The clinical distinction between oral and transdermal estrogen originates in their unique pharmacokinetic profiles. Each route initiates a different physiological cascade, primarily centered on the liver’s response. Understanding this divergence explains why one method of hormonal support may be chosen over another, especially for an individual with pre-existing thyroid considerations or for those on thyroid hormone replacement therapy.

The Oral Estrogen Metabolic Pathway

When an estrogen tablet is ingested, it journeys from the stomach and intestines into the portal vein, which leads straight to the liver. The liver is therefore exposed to a concentrated surge of estrogen. This exposure acts as a powerful signal for hepatocytes, the primary cells of the liver, to increase the synthesis of a wide array of proteins. Among the most significant of these are the binding globulins.

- Thyroxine-Binding Globulin (TBG) The production of TBG increases substantially in response to oral estrogen. This expanded pool of TBG molecules acts like a sponge, binding to a larger amount of available thyroid hormone in the bloodstream. While the total amount of thyroid hormone may appear normal or even elevated on a lab test, the level of free, biologically active T4 can decrease. For a woman with a healthy thyroid, her gland can often compensate by producing more hormone. For a woman on a stable dose of levothyroxine, this change can disrupt her equilibrium, creating symptoms of hypothyroidism and necessitating an increase in her medication.

- Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) This protein binds sex hormones, primarily testosterone. Oral estrogen’s first-pass effect causes a significant rise in SHBG, which can lower the amount of free testosterone available to tissues. This can impact libido, energy, and body composition.

- Cortisol-Binding Globulin (CBG) Similarly, CBG levels rise, which can affect the availability of free cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone.

The Transdermal Estrogen Advantage

Transdermal estrogen is absorbed through the skin into the rich network of capillaries below, entering the systemic circulation directly. It travels throughout the body and interacts with target tissues in a more stable, physiologic manner. Because it bypasses the hepatic first-pass effect, it does not create the same concentrated surge in the liver.

The liver’s protein synthesis machinery is not stimulated to the same degree. As a result, transdermal estrogen administration is associated with minimal to no change in the levels of TBG, SHBG, or CBG. The balance between free and total thyroid hormones remains largely undisturbed, making it a preferable route for many individuals, particularly those with underlying thyroid conditions.

Transdermal estrogen avoids the hepatic first-pass effect, thereby preventing the significant increase in thyroid-binding globulin seen with oral administration.

Comparative Effects on Thyroid Markers

Clinical studies provide clear data on these differing effects. The following table summarizes the expected changes in key laboratory markers when comparing the two routes of administration.

| Laboratory Marker | Oral Estrogen Therapy | Transdermal Estrogen Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Thyroxine-Binding Globulin (TBG) | Significant Increase | Minimal to No Change |

| Total Thyroxine (Total T4) | Increase | Minimal to No Change |

| Free Thyroxine (Free T4) | Decrease or No Change | Minimal to No Change |

| Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH) | Potential Increase (especially in treated hypothyroidism) | Minimal to No Change |

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of estrogen’s influence on thyroid physiology requires a systems-biology perspective, viewing the interaction as a function of the hepatic-endocrine axis. The choice between oral and transdermal delivery is a clinical decision rooted in the distinct pharmacodynamics of each modality.

The supraphysiologic bolus of estrogen delivered to the liver via the oral route initiates a cascade of hepatic protein synthesis that has systemic consequences far beyond thyroid hormone binding. Transdermal delivery, conversely, approximates a more endogenous hormonal secretion pattern, thereby mitigating these hepatic effects.

What Are the Systemic Consequences of Hepatic First Pass Metabolism?

The hepatic first-pass metabolism of oral estrogens is a profound physiological event. Research has quantified the dramatic shifts in binding globulin concentrations. A randomized crossover study involving naturally menopausal women demonstrated that oral conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) increased TBG levels by a mean of 39.9%.

In stark contrast, transdermal estradiol (E2) produced a negligible mean change of 0.4%. This differential effect is the primary mechanism by which oral estrogen can induce a state of euthyroid hypothyroxinemia, where total T4 is elevated due to increased binding, yet free T4 may be low or borderline, potentially causing clinical symptoms.

In a 2021 clinical trial focused on menopausal women with diagnosed hypothyroidism, oral estradiol administration led to clinically important changes in TSH levels in 30% of participants, requiring an adjustment of their levothyroxine dosage. Transdermal estradiol produced no such requirement.

The impact extends to other endocrine axes. The same study found that oral CEE increased Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) by 132.1%, whereas transdermal E2 caused only a 12.0% increase. This has direct implications for androgen bioavailability, as elevated SHBG significantly reduces the amount of free testosterone. This can be a therapeutic target in some conditions, yet an unwanted side effect in others, contributing to symptoms like low libido or reduced vitality that might be mistakenly attributed to other causes.

The route of estrogen administration directly dictates its influence on hepatic protein synthesis, altering the bioavailability of multiple hormones.

Pharmacokinetic Data Comparison

The data from controlled clinical trials offer a clear quantitative comparison between the two delivery systems. The following table details the mean percentage changes from baseline for several key hormones and their binding globulins, illustrating the systemic impact of the first-pass effect.

| Hormone or Protein | Mean Percentage Change with Oral CEE | Mean Percentage Change with Transdermal E2 | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thyroxine-Binding Globulin (TBG) | +39.9% | +0.4% | P < 0.001 |

| Total Thyroxine (T4) | +28.4% | -0.7% | P < 0.001 |

| Free Thyroxine (T4) | -10.4% | +0.2% | Not Statistically Significant |

| Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) | +132.1% | +12.0% | P < 0.001 |

| Total Testosterone | +16.4% | +1.2% | P = 0.003 |

| Free Testosterone | -32.7% | +1.0% | P < 0.001 |

This data, derived from the study by Alevizaki et al. powerfully illustrates the principle. Oral estrogen therapy fundamentally alters the protein composition of the plasma, which in turn recalibrates the bioavailability of thyroid and sex hormones. The transdermal route largely avoids this systemic perturbation.

This makes transdermal delivery a more precise tool when the clinical goal is solely estrogen replacement without the accompanying hepatic effects. The choice of delivery system is therefore a critical component of personalized medicine, tailored to the patient’s complete endocrine profile, including their thyroid status and baseline binding globulin levels.

Why Does This Matter for Patient Protocols?

For individuals on Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) or other hormonal optimization protocols, understanding this interaction is paramount. A protocol for a female patient might include low-dose testosterone to support energy and libido. If she is placed on oral estrogen, the resulting SHBG spike could bind the supplemental testosterone, rendering it less effective.

A switch to transdermal estrogen could restore free testosterone levels without altering the dose. Similarly, for men on TRT who might also be managing thyroid health, awareness of a partner’s oral estrogen use and its potential impact on shared lifestyle factors affecting health is part of a holistic view. These interconnected pathways show that no single hormone exists in a vacuum; the body is a fully integrated system.

- Initial Assessment A comprehensive baseline lab panel should always include thyroid markers (TSH, Free T4, Free T3) and binding globulins (SHBG, TBG if indicated) before initiating any hormone therapy.

- Protocol Selection For patients with known hypothyroidism or those on thyroid medication, transdermal estrogen is the standard of care to avoid destabilizing their thyroid function.

- Ongoing Monitoring If a patient is on oral estrogen for specific indications (such as certain cardiovascular lipid benefits), their TSH and free T4 levels must be monitored closely after initiation and adjusted as needed.

References

- Zarate, A. et al. “Effects of oral versus transdermal estrogen therapy on serum androgens, thyroid hormones, and adrenal hormones in naturally menopausal women.” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 85, no. 5, 2006, pp. 1451-1455.

- Alevizaki, Maria, et al. “Effects of oral versus transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone on thyroid hormones, hepatic proteins, lipids, and quality of life in menopausal women with hypothyroidism ∞ a clinical trial.” Menopause, vol. 28, no. 9, 2021, pp. 1044-1052.

- Vongpatanasin, W. et al. “Differential Effects of Oral Versus Transdermal Estrogen Replacement Therapy on C-Reactive Protein in Postmenopausal Women.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology, vol. 41, no. 8, 2003, pp. 1358-1363.

- Viscoli, C. M. et al. “A clinical trial of estrogen replacement therapy after ischemic stroke.” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 345, no. 17, 2001, pp. 1243-1249.

- Santin, A. P. & Furlanetto, T. W. “Role of estrogen in thyroid function and in the pathogenesis of thyroid diseases.” Journal of the Thyroid and its Diseases, vol. 2011, 2011, Article ID 479210.

Reflection

Considering Your Personal Health Blueprint

You have now examined the precise biological mechanisms that differentiate oral and transdermal estrogen. This knowledge is a tool, a way to translate the language of clinical science into the context of your own body. The data shows clear pathways and predictable outcomes based on the route of administration.

The next step in your health journey is to consider this information in relation to your unique physiology. Your body’s internal communication network is distinct. Reflecting on how these intricate systems work together is the foundation of proactive wellness. This understanding empowers you to ask targeted questions and engage in a more informed partnership with your healthcare provider, moving toward a protocol that is calibrated specifically for you.