Fundamentals

You may be following a meticulous diet and a consistent exercise regimen, yet the feeling of persistent fatigue remains. The numbers on the scale may refuse to move, and a pervasive sense of coldness might be your constant companion.

This experience, a profound disconnect between your efforts and your body’s response, often has its roots in the silent, powerful regulator of your physiology ∞ the thyroid gland. Understanding its role is the first step toward recalibrating your body’s internal economy and reclaiming your vitality.

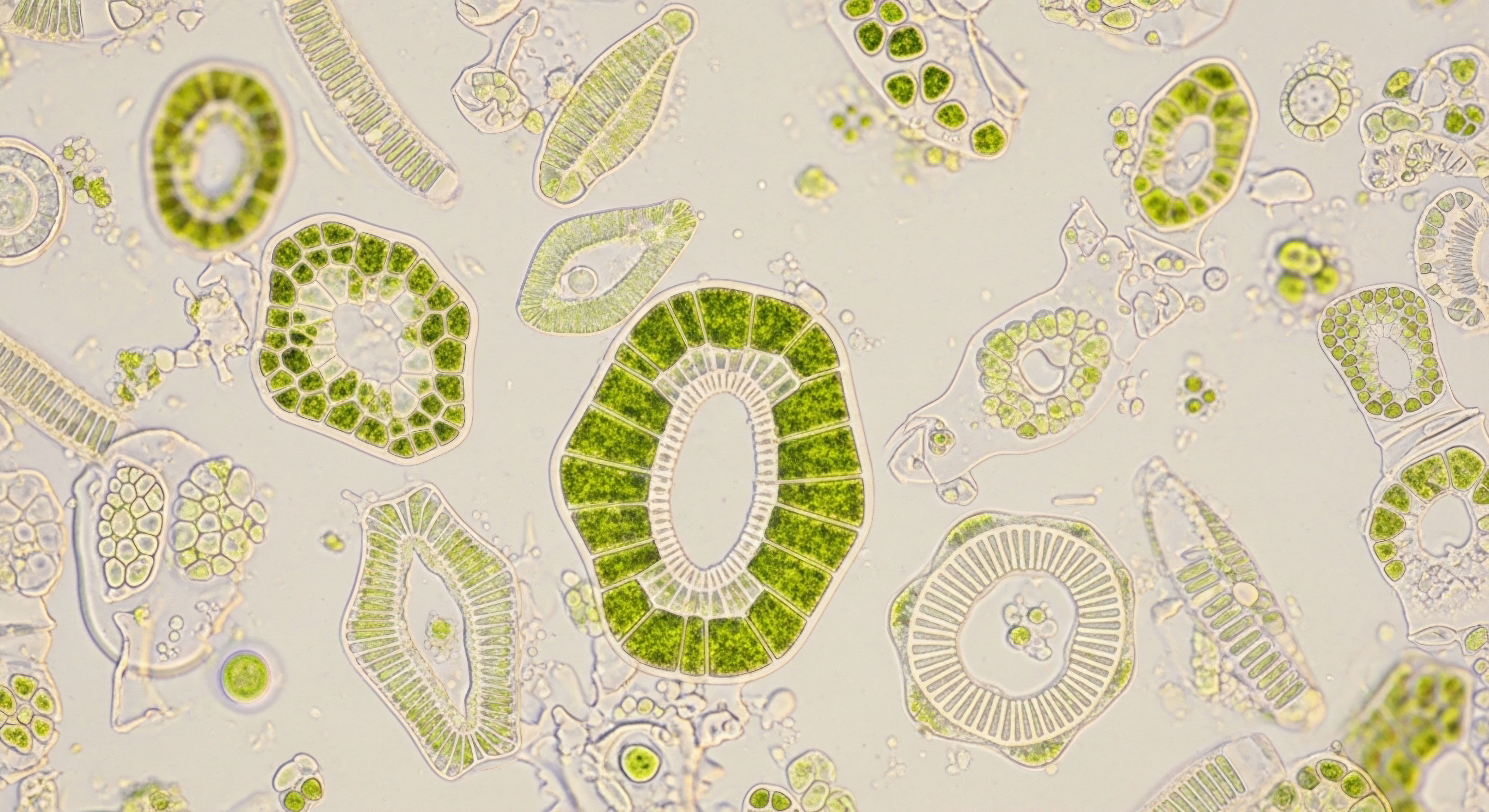

Your thyroid gland, a small butterfly-shaped organ at the base of your neck, functions as the master controller of your metabolic rate. It dictates the pace at which every cell in your body converts fuel from food into energy. This process is governed by two primary hormones ∞ thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3).

Think of T4 as the stable, abundant raw material produced by the thyroid. T3 is the potent, biologically active form of the hormone that directly interfaces with your cells. The majority of T3 is produced not in the thyroid itself, but in peripheral tissues like the liver and muscles, through a conversion process from T4.

The Cellular Power Grid

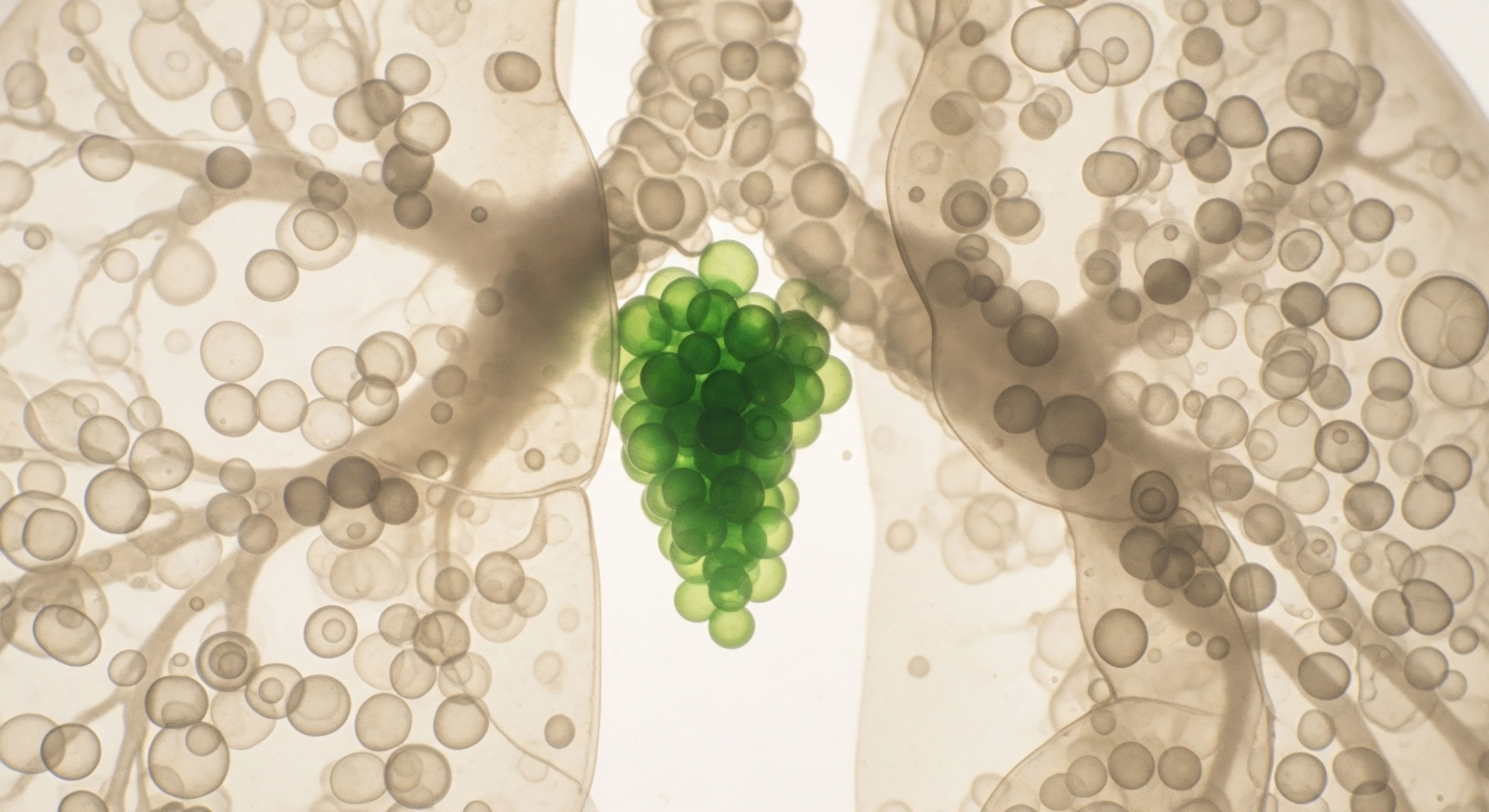

At the heart of this energy transaction are the mitochondria, the microscopic power plants within your cells. T3 is the signal that instructs these organelles on how much energy to produce. When T3 levels are optimal, your mitochondria operate efficiently, burning calories to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the energy currency that powers every heartbeat, every thought, and every movement.

This process also generates heat, which is why a healthy metabolism maintains a stable body temperature. When thyroid signaling falters, mitochondrial function slows down. The result is a system-wide energy deficit, manifesting as the very symptoms that disrupt your life ∞ fatigue, weight gain, brain fog, and cold intolerance.

Optimal thyroid function provides the essential instructions for cellular mitochondria to efficiently convert food into usable energy and heat.

A common scenario in clinical practice is subclinical hypothyroidism. In this state, your primary thyroid lab marker, Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH), is elevated, signaling that your brain is working harder to stimulate a sluggish thyroid. Your T4 levels might still fall within the standard laboratory range, yet you experience the full spectrum of hypothyroid symptoms. This condition represents an early stage of thyroid dysfunction, a subtle yet meaningful decline in metabolic efficiency that warrants careful investigation.

What Are the Signs of a Slowing Metabolism?

The symptoms associated with suboptimal thyroid function are systemic, reflecting the hormone’s widespread influence. Recognizing these signs is a key step in understanding your body’s needs.

| Category | Common Symptoms of Suboptimal Thyroid Function |

|---|---|

| Metabolic & Systemic | Unexplained weight gain or difficulty losing weight, persistent fatigue, increased sensitivity to cold, constipation, and a puffy face. |

| Skin & Hair | Dry skin, coarse or thinning hair, hair loss (including from the outer third of the eyebrows), and brittle nails. |

| Neurological & Mood | Depression, memory problems, difficulty concentrating (brain fog), and muscle weakness or aches. |

| Reproductive Health | Irregular or heavier menstrual cycles in women and decreased libido in both men and women. |

Intermediate

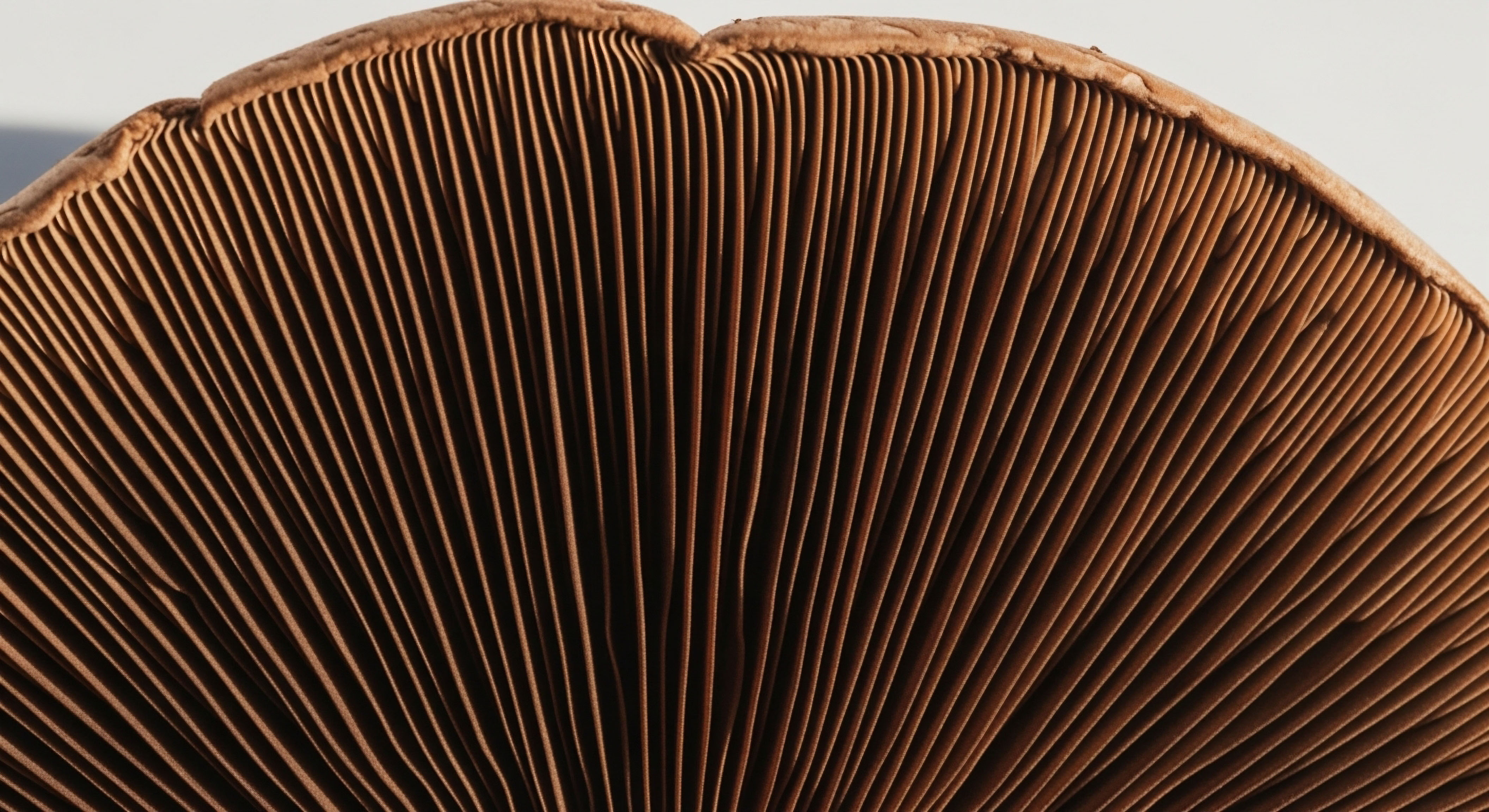

Achieving metabolic efficiency extends beyond the simple production of thyroid hormone. It hinges on a delicate and dynamic process of hormonal activation that occurs throughout the body. The conversion of the relatively inactive T4 prohormone into the powerful T3 active hormone is the true rate-limiting step for cellular energy production. This biochemical transformation is managed by a family of specialized enzymes called deiodinases, which act as the gatekeepers of your metabolic potential.

The Deiodinase System the Architects of Activation

Your body’s ability to fine-tune its metabolic rate at the tissue level is controlled by three primary deiodinase enzymes. Each has a distinct role and location, working in concert to maintain homeostasis.

- Deiodinase Type 1 (D1) ∞ Found predominantly in the liver and kidneys, D1 is responsible for contributing a significant portion of the circulating T3 in your bloodstream. Its function can be suppressed by factors like chronic stress and inflammation, reducing the overall availability of active thyroid hormone.

- Deiodinase Type 2 (D2) ∞ This enzyme is a master regulator of local T3 levels within specific tissues, including the brain, pituitary gland, and skeletal muscle. D2 is incredibly efficient at converting T4 to T3, ensuring these critical areas get the energy they need. Its activity increases during periods of physiological stress, attempting to compensate for systemic slowdowns.

- Deiodinase Type 3 (D3) ∞ Functioning as a metabolic brake, D3 is the primary inactivating enzyme. It converts T4 into an inert metabolite known as reverse T3 (rT3) and also degrades active T3. During times of significant stress, illness, or prolonged calorie restriction, D3 activity increases, effectively putting a hold on metabolic activity to conserve energy.

The balance between the activity of these enzymes determines your true thyroid status. A high level of reverse T3, for instance, can competitively block T3 receptors on your cells, leading to symptoms of hypothyroidism even when circulating T3 and T4 levels appear normal. This is why a comprehensive thyroid panel, one that measures TSH, free T4, free T3, and reverse T3, provides a much clearer picture of your metabolic health.

The conversion of T4 to T3 by deiodinase enzymes is the critical step that determines the amount of active thyroid hormone available to power cellular metabolism.

Why Does Thyroid Conversion Slow Down?

Several physiological and lifestyle factors can disrupt the delicate balance of deiodinase activity, shifting the system towards conservation and away from efficient energy expenditure. Understanding these impediments is foundational to any optimization protocol.

Chronic stress is a primary disruptor. The persistent elevation of the stress hormone cortisol suppresses D1 activity and promotes the conversion of T4 to inactive rT3 via the D3 enzyme. This is a protective adaptation designed for short-term survival, but in the context of modern chronic stress, it results in a sustained metabolic downturn.

Likewise, nutrient insufficiencies can cripple the conversion process. The deiodinase enzymes are selenium-dependent proteins, meaning they require adequate selenium to function. Other micronutrients, including zinc and iron, also play integral roles in hormone synthesis and conversion.

| Factor | Mechanism of Impairment | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic Stress (High Cortisol) | Suppresses D1 activity and upregulates D3, increasing the production of inactive reverse T3. | Leads to fatigue and weight gain despite “normal” T4 levels. A primary target for lifestyle and adaptogenic interventions. |

| Caloric Restriction | The body perceives severe dieting as a famine state, increasing rT3 to conserve energy and lower the metabolic rate. | Explains why extreme diets often lead to weight loss plateaus and subsequent rebound weight gain. |

| Systemic Inflammation | Inflammatory cytokines interfere with deiodinase function, particularly D1 and D2, impairing T3 production. | Chronic infections, autoimmune conditions like Hashimoto’s, and gut dysbiosis can all drive thyroid resistance. |

| Nutrient Deficiencies | Deiodinase enzymes require selenium. Iron is needed for thyroid peroxidase (TPO) function. Zinc supports T3 receptor sensitivity. | Targeted nutritional support is a cornerstone of improving thyroid hormone conversion and overall metabolic health. |

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of metabolic efficiency requires moving beyond a singular focus on the thyroid gland and examining its intricate connections within the broader neuroendocrine system. Metabolic optimization is achieved through the coordinated function of multiple hormonal axes, principally the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) axis, the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, and the pathways governing insulin sensitivity. Dysfunction in one system inevitably perturbs the others, creating a cascade of metabolic dysregulation that defines many modern chronic conditions.

The HPA-HPT Axis Crosstalk a Mechanism for Survival

The body’s response to stress, mediated by the HPA axis and its primary effector hormone, cortisol, has a profound and direct impact on thyroid physiology. In an acute stress scenario, this interaction is adaptive. In the context of chronic psychological, inflammatory, or metabolic stress, it becomes deeply maladaptive.

Chronically elevated cortisol exerts suppressive effects at multiple levels of the HPT axis. It can reduce the hypothalamic release of Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone (TRH) and blunt the pituitary’s sensitivity to it, leading to a decrease in Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH) secretion.

More significantly, cortisol directly modulates peripheral thyroid hormone metabolism. It inhibits the activity of the D1 and D2 deiodinase enzymes, thereby reducing the systemic and intracellular conversion of T4 to active T3. Concurrently, it upregulates the D3 enzyme, shunting T4 toward the production of inactive reverse T3 (rT3).

This coordinated response effectively lowers the body’s metabolic thermostat, a physiological strategy designed to conserve energy during a perceived crisis. When the crisis becomes chronic, the result is a state of cellular or functional hypothyroidism, characterized by symptoms of a slowed metabolism despite potentially normal TSH and T4 readings.

Chronic activation of the HPA axis suppresses the HPT axis, leading to impaired T4-to-T3 conversion and a systemic decrease in metabolic rate as a protective, energy-conserving measure.

Thyroid Function and Insulin Resistance a Bidirectional Relationship

The interplay between thyroid hormones and insulin is another critical determinant of metabolic efficiency. Thyroid hormones are essential for proper glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity. T3 enhances insulin-mediated glucose uptake in peripheral tissues like skeletal muscle and adipose tissue. It also supports pancreatic beta-cell function, the cells responsible for insulin secretion.

Consequently, even subclinical hypothyroidism can contribute to the development of insulin resistance. A reduced metabolic rate leads to decreased glucose utilization by cells, which can elevate blood glucose levels and necessitate higher insulin output. Over time, this can lead to cellular desensitization to insulin’s signal.

The relationship is bidirectional; insulin resistance itself places significant metabolic stress on the body, which can further suppress thyroid function through inflammatory pathways and by contributing to HPA axis dysregulation. This creates a self-perpetuating cycle where poor thyroid function worsens insulin sensitivity, and poor insulin sensitivity further impairs thyroid hormone conversion and action, ultimately crippling metabolic efficiency.

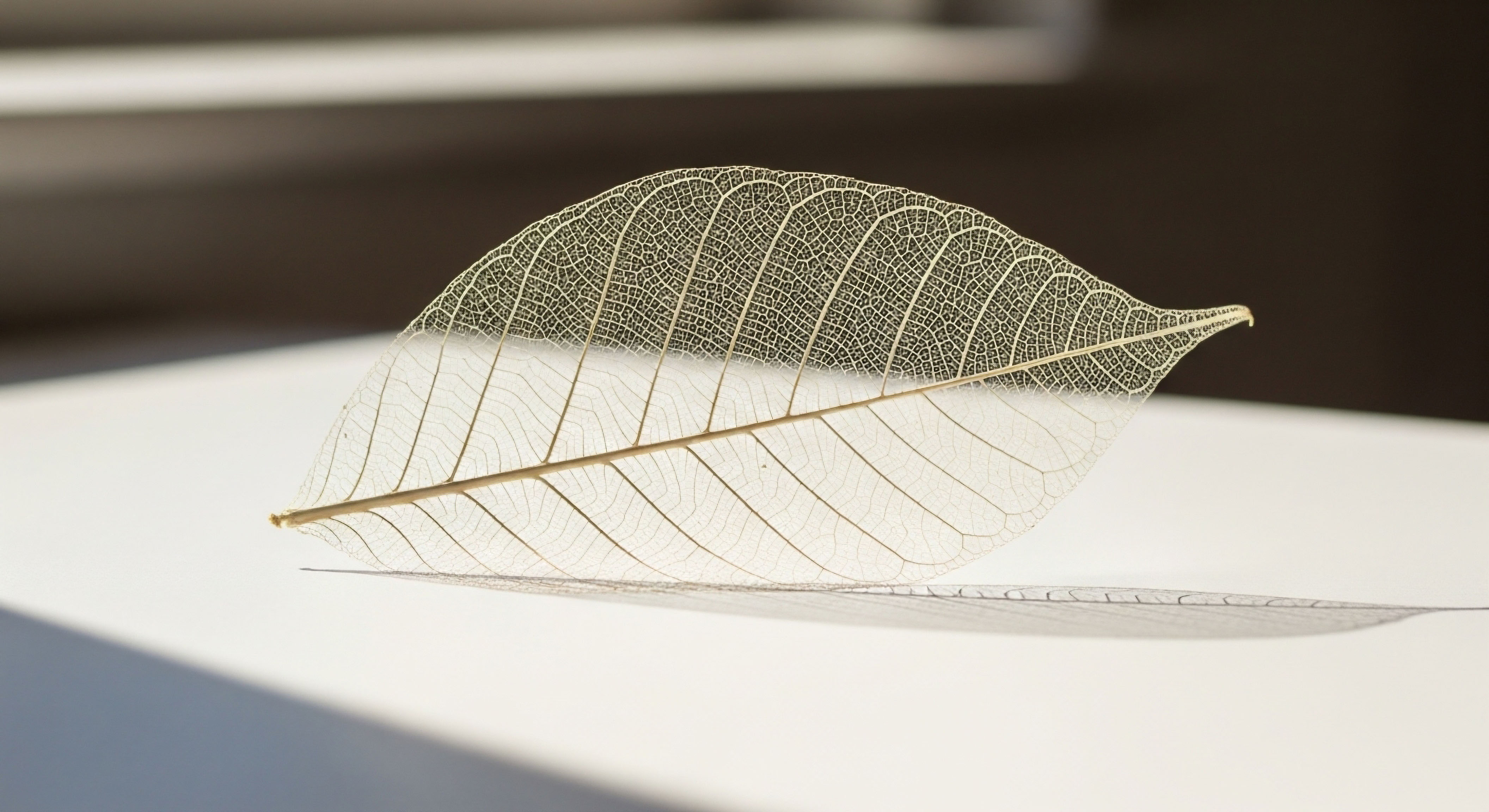

Thermogenesis the Engine of Metabolic Rate

The most direct expression of metabolic rate is thermogenesis, the production of heat. Thyroid hormones are primary drivers of this process, acting on specialized tissues to dissipate energy. A key mechanism is the induction of Uncoupling Protein 1 (UCP1) in brown adipose tissue (BAT).

UCP1 creates a “proton leak” across the inner mitochondrial membrane, uncoupling the process of oxidative phosphorylation from ATP synthesis. Instead of producing chemical energy (ATP), the energy from fuel oxidation is released directly as heat. This metabolically “inefficient” process is a primary way homeotherms maintain body temperature and a major contributor to total daily energy expenditure.

Optimal T3 levels are required for both the expression of UCP1 and the sympathetic nervous system activation that stimulates BAT thermogenesis, making thyroid function a direct controller of this energy-burning pathway.

References

- Lombardi, A. et al. “Mitochondrial Actions of Thyroid Hormone.” Comprehensive Physiology, vol. 6, no. 4, 2016, pp. 1591-1607.

- Bianco, A. C. et al. “Metabolism of Thyroid Hormone.” Endotext, edited by K. R. Feingold et al. MDText.com, Inc. 2017.

- Mullur, R. et al. “Thyroid Hormone Regulation of Metabolism.” Physiological Reviews, vol. 94, no. 2, 2014, pp. 355-382.

- Silva, J. E. “Thyroid hormone control of thermogenesis and energy balance.” Thyroid, vol. 5, no. 6, 1995, pp. 481-92.

- Harper, M. E. and E. L. Seifert. “Thyroid hormone effects on mitochondrial energetics.” Thyroid, vol. 18, no. 2, 2008, pp. 145-56.

- Biondi, B. and D. S. Cooper. “The clinical significance of subclinical thyroid dysfunction.” Endocrine Reviews, vol. 29, no. 1, 2008, pp. 76-131.

- Gereben, B. et al. “Cellular and molecular basis of deiodinase-regulated thyroid hormone signaling.” Endocrine Reviews, vol. 29, no. 7, 2008, pp. 898-938.

- Oetting, A. and J. D. Yen. “Thyroid hormone and thermogenesis.” Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity, vol. 14, no. 5, 2007, pp. 347-52.

- Walter, K. N. et al. “The role of cortisol in the clinical expression of subclinical hypothyroidism.” Thyroid, vol. 22, no. 11, 2012, pp. 1094-100.

- Roos, A. et al. “Thyroid function is associated with components of the metabolic syndrome in euthyroid subjects.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 92, no. 2, 2007, pp. 491-6.

Reflection

A New Framework for Your Health

The information presented here provides a biological blueprint, connecting symptoms that may have felt random and disconnected to a unified, logical system. This knowledge shifts the perspective from one of frustration with a body that seems to be failing, to one of curiosity about a body that is communicating its needs.

Your lived experience of fatigue, of weight that resists your best efforts, is valid. It is a subjective manifestation of an objective, measurable physiological state. The feelings are real because the biology is real.

This understanding is the starting point. It equips you to ask more precise questions and to seek a more comprehensive evaluation of your health. It forms the basis for a collaborative partnership with a clinician who recognizes that optimizing complex systems requires a personalized approach.

Your journey forward involves looking at your own data, understanding your unique stressors, and identifying the specific factors that may be impeding your metabolic machinery. This is how you begin to move from a state of surviving to one of functioning at your full biological potential.

Glossary

metabolic rate

weight gain

subclinical hypothyroidism

metabolic efficiency

thyroid function

thyroid hormone

deiodinase enzymes

chronic stress

reverse t3

cortisol

insulin sensitivity

hpa axis

thyroid hormones

insulin resistance