Fundamentals

The sensation of profound fatigue or a subtle decline in vitality often prompts a search for answers that lie deeper than surface-level explanations. You may feel that your body is no longer functioning with the same efficiency it once did, a feeling that is both valid and biologically significant.

This experience is frequently connected to changes within your body’s core regulatory systems. One of the most central of these systems involves a type of fat you cannot see or touch, known as visceral fat. This is the fat stored deep within your abdominal cavity, surrounding crucial organs like your liver, pancreas, and intestines.

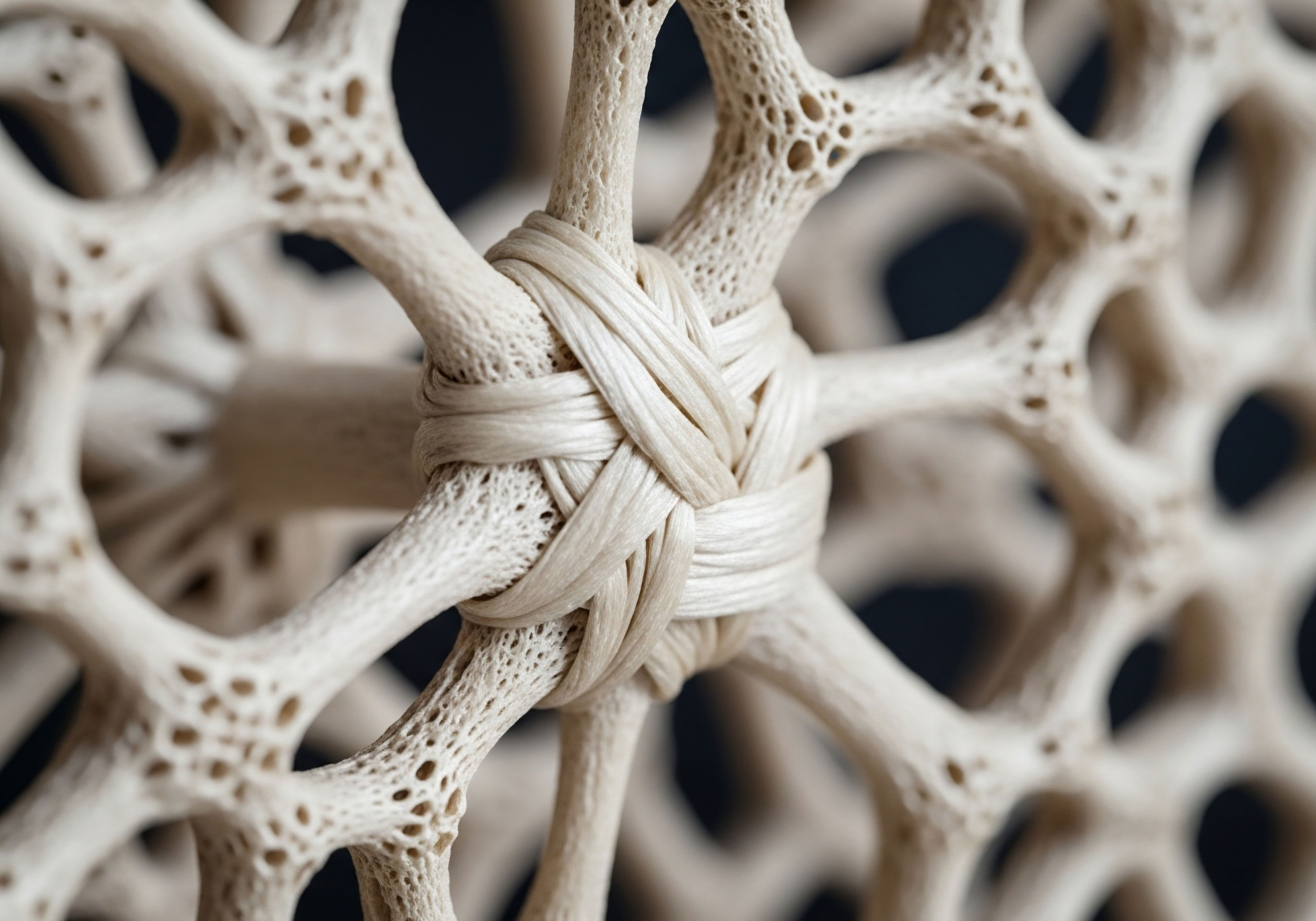

Visceral adipose tissue functions as a dynamic, active endocrine organ. It is a sophisticated factory for producing and releasing a host of signaling molecules that communicate with every system in your body. When this internal fat deposit is minimal, it performs its duties quietly and effectively, supporting metabolic balance.

An accumulation of excess visceral fat, however, alters its function. It begins to transmit disruptive signals, creating a state of internal imbalance that directly affects your long-term health, particularly the resilience and function of your cardiovascular system.

The Body’s Internal Communication Network

Consider your hormonal system as the body’s internal messaging service, a complex network of signals that regulate everything from energy levels to mood and metabolic rate. Hormones are the chemical messengers, and their receptors on cells are the receiving stations. Visceral fat directly participates in this communication network.

It secretes substances called adipokines, which are a class of hormones and inflammatory molecules that have powerful effects throughout the body. In healthy amounts, these signals are beneficial. When visceral fat becomes excessive, the volume and nature of these signals change, overwhelming the system with disruptive information.

This disruption is a primary driver of systemic inflammation. An overabundance of visceral fat leads to a state of chronic, low-grade inflammation, a persistent activation of the immune system that underpins many age-related health challenges. This inflammatory state is not an abstract concept; it has tangible effects on your blood vessels, heart, and metabolic health.

Reducing visceral fat is therefore a process of recalibrating this internal communication system, quieting the inflammatory signals, and restoring a state of biological equilibrium that is essential for longevity.

Reducing visceral fat quiets the inflammatory signals that disrupt cardiovascular function and metabolic balance.

From Organ Cushion to Endocrine Disruptor

Visceral fat serves a protective purpose in small quantities, cushioning your internal organs. Its transformation into a source of metabolic disruption is a gradual process, often linked to hormonal shifts and lifestyle factors. The accumulation of this deep abdominal fat is a physical manifestation of underlying metabolic and endocrine dysregulation. Its presence is a reliable indicator of an internal environment that is becoming less efficient at managing energy, regulating blood sugar, and maintaining vascular health.

The direct impact on heart health originates from the unique circulatory connection of visceral fat. The blood that flows from visceral adipose tissue drains directly into the liver via the portal vein. This means that the inflammatory molecules and fatty acids released by this fat depot have immediate and concentrated access to the liver, where they can disrupt cholesterol production and impair insulin sensitivity.

This direct biological link is what makes visceral fat a particularly potent contributor to cardiovascular risk. Addressing it is a foundational step in any personalized wellness protocol aimed at preserving long-term vitality.

Intermediate

Understanding the connection between visceral fat and cardiovascular health requires moving beyond the general concept of inflammation and into the specific biochemical messengers involved. Visceral adipose tissue (VAT) is a primary source of several potent adipokines that directly influence vascular biology and metabolic function. The reduction of VAT fundamentally alters the balance of these signals, shifting the body from a pro-inflammatory, pro-thrombotic state to one that supports cardiovascular resilience.

Two of the most critical adipokines in this context are adiponectin and leptin. Adiponectin is a protein hormone that is almost exclusively secreted by fat cells. It has powerful anti-inflammatory and insulin-sensitizing effects. Adiponectin enhances the ability of muscle and liver cells to use glucose, protects the lining of blood vessels (the endothelium), and reduces the inflammatory processes that lead to atherosclerosis.

Paradoxically, as visceral fat mass increases, adiponectin secretion decreases. This reduction in a key protective molecule leaves the cardiovascular system more vulnerable.

Leptin, on the other hand, is primarily known for its role in regulating appetite and energy balance. In a healthy system, leptin signals to the brain that energy stores are sufficient. With excessive VAT, leptin levels become chronically elevated. The brain becomes resistant to its signal, a condition known as leptin resistance.

This state is associated with increased sympathetic nervous system activity, which can raise blood pressure, and it also promotes inflammatory responses within blood vessels. Reducing visceral fat helps to lower circulating leptin levels and restore sensitivity to its signals, thereby decreasing a key driver of hypertension and vascular inflammation.

The Inflammatory Cascade of Visceral Adipose Tissue

Excessive VAT becomes infiltrated by immune cells, particularly macrophages, which further amplify the production of inflammatory cytokines. This creates a self-perpetuating cycle of inflammation. The table below outlines some of the key molecules released by hypertrophied visceral adipocytes and their direct impact on cardiovascular health.

| Secreted Molecule | Primary Cardiovascular Impact |

|---|---|

| Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) | Promotes insulin resistance in muscle and liver cells, increases the production of other inflammatory markers, and contributes to endothelial dysfunction. |

| Interleukin-6 (IL-6) | Stimulates the liver to produce C-reactive protein (CRP), a primary clinical marker of systemic inflammation. High levels of IL-6 are directly linked to increased cardiovascular event risk. |

| Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) | This protein inhibits the breakdown of blood clots. Elevated levels, strongly correlated with visceral adiposity, create a pro-thrombotic state that increases the risk of heart attack and stroke. |

| Angiotensinogen | As a precursor to angiotensin II, this molecule contributes to vasoconstriction and increases blood pressure. VAT is a significant extra-renal source of angiotensinogen. |

Reducing visceral fat directly lessens the secretion of these harmful molecules. This is a primary mechanism by which cardiovascular risk is lowered. The decrease in TNF-α and IL-6 reduces the overall inflammatory burden on the vascular system, while the reduction in PAI-1 restores a healthier balance in the body’s clotting system. The entire cardiovascular environment becomes less reactive and more stable.

A reduction in visceral fat directly lowers the circulating levels of specific proteins that promote blood clotting and vascular inflammation.

How Does Visceral Fat Reduction Improve Endothelial Function?

The endothelium is the thin layer of cells lining the inside of your blood vessels. Its health is paramount for cardiovascular longevity. A healthy endothelium produces nitric oxide, a molecule that allows blood vessels to relax and widen, ensuring smooth blood flow.

The inflammatory state created by excess visceral fat impairs the endothelium’s ability to produce nitric oxide, a condition known as endothelial dysfunction. This is a critical early step in the development of atherosclerosis, the process of plaque buildup in the arteries.

When visceral fat is reduced, the inflammatory assault on the endothelium ceases. The decrease in circulating TNF-α and other cytokines allows the endothelial cells to function properly again. They can resume adequate production of nitric oxide, which has several protective effects:

- Improved Vasodilation ∞ Blood vessels can relax and expand appropriately, which helps to regulate blood pressure.

- Reduced Platelet Aggregation ∞ The “stickiness” of platelets is reduced, making it less likely for unwanted clots to form on the vessel wall.

- Decreased Monocyte Adhesion ∞ Inflammatory white blood cells are less likely to stick to the vessel lining, a key step in the formation of atherosclerotic plaques.

This restoration of endothelial function is one of the most direct and impactful benefits of visceral fat reduction on long-term heart health. It is a fundamental repair process at the cellular level of the cardiovascular system.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of visceral adiposity’s impact on cardiovascular health requires a systems-biology perspective, examining the tissue’s role as a nexus of endocrine, metabolic, and inflammatory signaling. The detrimental effects of visceral adipose tissue (VAT) extend far beyond simple mass effect; VAT actively secretes a complex milieu of adipokines and free fatty acids (FFAs) that directly instigates the pathophysiology of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).

The portal circulation theory provides a critical framework for this understanding ∞ because VAT’s venous drainage flows directly to the liver, the hepatocytes are exposed to a high concentration of these bioactive molecules, initiating a cascade of metabolic dysregulation.

High portal concentrations of FFAs released from lipolytically active visceral adipocytes lead to hepatic insulin resistance. This impairs the liver’s ability to suppress glucose production and increases the synthesis of very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL), contributing to the characteristic atherogenic dyslipidemia seen in metabolic syndrome ∞ elevated triglycerides, reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and an increase in small, dense low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles. This lipid profile is profoundly pro-atherogenic.

The Pathophysiological Link between Adipokines and Atherogenesis

The progression from endothelial dysfunction to a stable atherosclerotic plaque is a multi-step process orchestrated in large part by the inflammatory cytokines secreted from VAT. Interleukin-6 and TNF-α, for instance, promote a pro-inflammatory phenotype in endothelial cells. This results in the upregulation of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1). These molecules facilitate the adhesion of circulating monocytes to the endothelium.

Once adhered, these monocytes migrate into the subendothelial space, or intima, where they differentiate into macrophages. Simultaneously, the pro-inflammatory environment promotes the oxidation of LDL particles that have also entered the intima. Macrophages express scavenger receptors that recognize and internalize these oxidized LDL particles, becoming engorged with lipids and transforming into foam cells.

The accumulation of these foam cells constitutes the fatty streak, the earliest visible lesion of atherosclerosis. The reduction of VAT directly attenuates this foundational process by lowering the systemic and portal concentrations of the cytokines that initiate it.

What Is the Role of Perivascular Adipose Tissue?

Perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT), the fat depot surrounding most blood vessels, adds another layer of complexity. Under physiological conditions, PVAT exerts an anti-contractile, vasodilatory effect on the underlying vessel, mediated by the secretion of protective factors like adiponectin and nitric oxide. In states of obesity and high visceral adiposity, PVAT itself becomes inflamed and dysfunctional.

It switches from a protective to a pro-inflammatory secretome, releasing vasoconstrictive and pro-inflammatory factors directly onto the vessel wall. This localized paracrine signaling accelerates the atherosclerotic process within that specific vascular bed.

The reduction of visceral fat helps restore the protective, anti-inflammatory function of the fat tissue immediately surrounding blood vessels.

The table below details the functional shift in perivascular adipose tissue.

| Characteristic | Physiological PVAT (Lean State) | Pathological PVAT (Visceral Obesity) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Secretions | Adiponectin, Nitric Oxide, Hydrogen Sulfide | TNF-α, IL-6, MCP-1, Leptin, Angiotensinogen |

| Effect on Vessel Tone | Anti-contractile, promotes vasodilation | Promotes vasoconstriction and vascular stiffness |

| Immune Cell Profile | Anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages, regulatory T cells | Pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages, cytotoxic T cells |

| Overall Vascular Impact | Atheroprotective | Pro-atherogenic, promotes plaque instability |

Hormonal Axis Dysregulation and Cardiometabolic Feedback Loops

The chronic inflammatory state driven by VAT has profound implications for the body’s central hormonal regulatory systems, including the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. Systemic inflammation can suppress the pulsatile release of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus. This, in turn, reduces the secretion of Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) from the pituitary.

In men, this can lead to secondary hypogonadism, characterized by low testosterone levels. Low testosterone itself promotes the accumulation of visceral fat, creating a deleterious feedback loop.

In women, particularly during the peri- and post-menopausal transition, the decline in estrogen is associated with a redistribution of fat storage, favoring visceral deposition. This VAT then becomes a significant source of inflammation, further exacerbating metabolic dysfunction. Therefore, therapeutic interventions must consider this bidirectional relationship.

Protocols involving Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) in men or hormonal optimization in women can help break this cycle by altering body composition and reducing VAT accumulation. This hormonal support, combined with lifestyle interventions, addresses both the cause and the effect, leading to a more robust improvement in the cardiometabolic risk profile.

- Visceral Fat Accumulation ∞ Leads to increased secretion of IL-6 and TNF-α.

- Systemic Inflammation ∞ These cytokines disrupt hypothalamic GnRH pulsatility.

- HPG Axis Suppression ∞ Results in decreased LH/FSH output and lower gonadal steroid production (testosterone/estrogen).

- Hormonal Deficiency ∞ Low testosterone or estrogen further promotes the preferential storage of visceral fat.

- Cycle Reinforcement ∞ The newly accumulated VAT secretes more inflammatory cytokines, perpetuating the cycle.

Reducing visceral fat is a direct intervention in this cycle. It lowers the inflammatory load, allowing for the potential normalization of HPG axis function. This demonstrates that managing body composition is a critical component of endocrine health, just as optimizing endocrine health is a critical component of managing body composition and cardiovascular longevity.

References

- Fain, J. N. “Release of inflammatory mediators by human adipose tissue is enhanced in obesity and primarily by the nonfat cells.” Vitam Horm, vol. 80, 2009, pp. 445-56.

- Fantuzzi, G. “Adipose tissue, adipokines, and inflammation.” Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, vol. 115, no. 5, 2005, pp. 911-9.

- Fontana, L. et al. “Visceral fat adipokine secretion is associated with systemic inflammation in obese humans.” Diabetes, vol. 56, no. 4, 2007, pp. 1010-3.

- Kershaw, E. E. and J. S. Flier. “Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 89, no. 6, 2004, pp. 2548-56.

- Van der Zijl, N. J. et al. “The role of visceral versus subcutaneous fat in the metabolic syndrome.” Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America, vol. 37, no. 3, 2008, pp. 687-706.

- Wajchenberg, B. L. “Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue ∞ their relation to the metabolic syndrome.” Endocrine Reviews, vol. 21, no. 6, 2000, pp. 697-738.

- Almhaini, S. et al. “Visceral adipose tissue and residual cardiovascular risk ∞ a pathological link and new therapeutic options.” Cardiovascular Diabetology, vol. 22, no. 1, 2023, p. 199.

- Klöting, N. and M. Blüher. “Adipocyte dysfunction, inflammation and metabolic syndrome.” Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders, vol. 15, no. 4, 2014, pp. 277-87.

- Mathieu, P. et al. “Visceral obesity and the heart.” International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, vol. 42, no. 9, 2010, pp. 1431-5.

- Tchernof, A. and J. P. Després. “Pathophysiology of visceral obesity.” Clinical in Plastic Surgery, vol. 34, no. 1, 2007, pp. 1-12.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a biological and chemical blueprint for understanding how your body’s internal environment influences its long-term function. You have seen how a specific type of internal fat acts as a powerful signaling hub, capable of either supporting or disrupting the systems that govern your health.

This knowledge shifts the perspective from a general goal of “weight loss” to a precise, targeted objective of recalibrating your body’s internal chemistry. The journey toward optimal function begins with understanding these intricate connections within your own physiology.

This clinical science is the foundation, the map that illustrates the territory. Your personal experience, the way you feel day-to-day, is the starting point on that map. The path forward involves aligning your biological reality with your wellness goals. Consider how these systems might be operating within you.

This self-awareness, informed by an understanding of the underlying mechanisms, is the first and most critical step in taking deliberate, effective action toward reclaiming a state of vitality that is not just remembered, but actively experienced.

Glossary

visceral fat

visceral adipose tissue

endocrine organ

adipokines

systemic inflammation

adipose tissue

adiponectin

leptin resistance

nitric oxide

endothelial dysfunction

cardiovascular disease

insulin resistance

metabolic syndrome

interleukin-6

perivascular adipose tissue