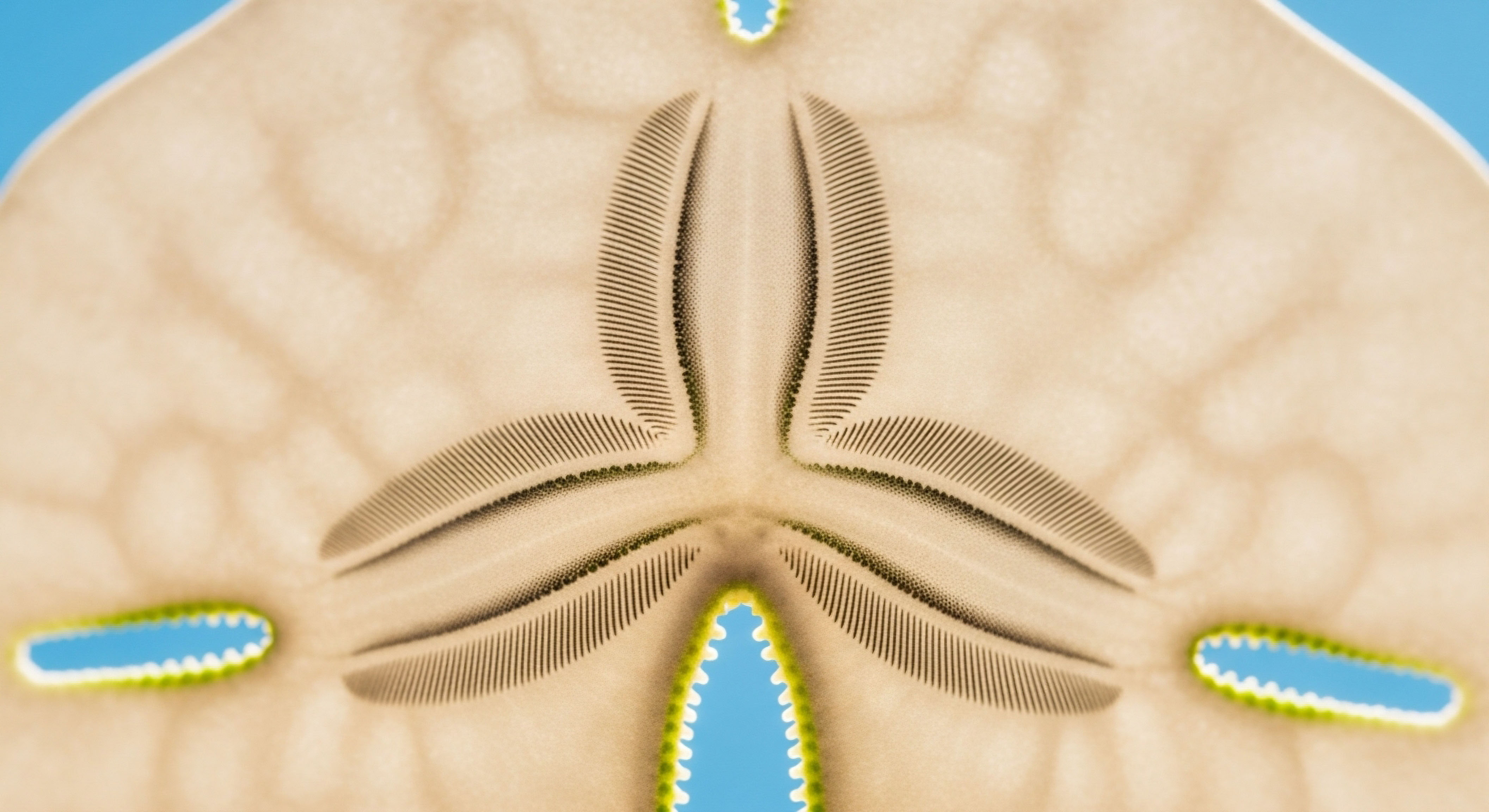

Fundamentals

Your Autonomy in Corporate Wellness

The concept of a “voluntary” wellness program, particularly when tied to financial incentives, touches upon the very core of your personal health autonomy. Your decision to share personal health information or participate in a medical screening is a significant one. It involves a level of trust and personal disclosure that should be entirely within your control.

When your employer offers a financial reward for participation ∞ or a penalty for non-participation ∞ the line between encouragement and coercion can become blurred. The central question from a physiological and legal standpoint is this ∞ at what point does a financial incentive become so significant that it overrides your ability to make a truly free choice about your own body and health data?

This is not merely a legal distinction; it is a biological one. A substantial financial pressure can initiate a physiological stress response, influencing decision-making processes. Understanding the legal framework is the first step in protecting your agency in this dynamic.

Federal regulations exist to create a boundary, ensuring that such programs serve their intended purpose of promoting health without infringing upon your rights. The law attempts to balance an employer’s interest in fostering a healthy workforce with your fundamental right to privacy and freedom from discrimination.

The legal definition of “voluntary” is constructed through a dialogue between several key pieces of legislation. These laws collectively create a set of rules that dictate how wellness programs can be designed and implemented, especially when they ask for sensitive health information or require medical examinations.

The legal framework aims to ensure that your participation in a wellness program is a genuine choice, not a financially compelled mandate.

The Core Legal Pillars

To appreciate the nuances of “voluntary” participation, it is helpful to recognize the primary laws that govern these programs. Each law addresses the issue from a different angle, together forming a complex regulatory environment. Think of these as different specialists contributing to a single patient’s care plan, each with a unique perspective.

- The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) ∞ This act is fundamental. The ADA generally prohibits employers from asking employees for health information or requiring them to undergo medical exams. An exception is made for “voluntary” employee health programs. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), which enforces the ADA, has provided guidance stating that a program is voluntary if the employer does not require participation or penalize employees who choose not to participate. The debate centers on whether a large financial incentive is, in effect, a penalty for non-participation.

- The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) ∞ This law protects you from discrimination based on your genetic information. GINA is particularly relevant when wellness programs ask for family medical history, which is considered genetic information. Like the ADA, it allows for the collection of this information only as part of a voluntary program.

- The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) ∞ As part of its nondiscrimination provisions, HIPAA permits group health plans to offer premium discounts or other rewards for participation in wellness programs. It sets specific standards for how these programs must be designed, particularly for those that are health-contingent (meaning you must achieve a health goal to get the reward).

- The Affordable Care Act (ACA) ∞ The ACA expanded on HIPAA’s wellness program provisions, most notably by increasing the maximum permissible financial incentive. It allows for incentives of up to 30% of the total cost of self-only health coverage, and potentially up to 50% for programs designed to prevent or reduce tobacco use. This increase intensified the debate over what constitutes a truly voluntary program.

These laws do not operate in isolation. Their overlapping and sometimes conflicting standards have created a complex legal landscape that employers must navigate. For you, the employee, the key takeaway is that there are established legal protections designed to keep your participation voluntary. The financial incentives, while permissible, are subject to limits and conditions to prevent them from becoming coercive.

Intermediate

The Incentive Threshold and Coercion

The transition from a simple, educational wellness initiative to one involving significant financial incentives marks a critical shift in the dynamic between employer and employee. This is where the legal definition of “voluntary” is most rigorously tested.

The core of the issue lies in determining the threshold at which an incentive ceases to be a mere encouragement and becomes a form of economic coercion. From a clinical perspective, this is akin to understanding a dose-response relationship in medicine.

A low dose of a medication may be beneficial, while a high dose can become toxic. Similarly, a small incentive, like a gift card or a t-shirt, is unlikely to unduly influence your decision. However, when the incentive represents a substantial portion of your health insurance premium, the pressure to participate can feel immense, potentially compromising the voluntary nature of your choice.

The law attempts to quantify this threshold. Under the ACA, the incentive limit was set at 30% of the total cost of self-only health coverage. For example, if the total annual premium for your health plan is $6,000, the maximum incentive your employer can offer is $1,800.

This can be structured as either a reward for participating or a penalty (in the form of a higher premium) for not participating. The EEOC, in its 2016 guidance that was later vacated, adopted this same 30% threshold for programs that require medical examinations or ask disability-related questions under the ADA.

The reasoning was to create a consistent standard across the different regulations. The central premise is that this 30% cap is significant enough to encourage participation but not so large as to be effectively mandatory for the average worker.

The law quantifies the boundary of voluntariness by setting a percentage-based limit on financial incentives, aiming to prevent economic coercion.

How Are Different Program Types Regulated?

The level of legal scrutiny applied to a wellness program depends heavily on its design. The law makes a key distinction between two categories of programs, based on what is required to earn the incentive. Understanding this distinction is vital to understanding your rights.

- Participatory Wellness Programs ∞ These programs do not require you to meet a health-related standard to earn a reward. Participation is the only requirement. Examples include attending a series of health education seminars, completing a health risk assessment (HRA) without any requirement for results, or certifying that you have had an annual physical. Because these programs are less intrusive and do not penalize individuals based on their health status, they are subject to fewer regulations under HIPAA and the ACA. However, if a participatory program includes a disability-related inquiry or a medical exam (like an HRA or biometric screening), it must still comply with the ADA’s voluntariness requirement.

-

Health-Contingent Wellness Programs ∞ These programs require you to satisfy a standard related to a health factor to obtain a reward. They are more heavily regulated because of the potential for discrimination based on health status. There are two sub-types:

- Activity-Only Programs ∞ These require you to perform a specific activity related to a health factor, but do not require you to achieve a specific outcome. Examples include walking programs or exercise challenges.

- Outcome-Based Programs ∞ These require you to attain or maintain a specific health outcome to get the reward. Examples include achieving a certain BMI, cholesterol level, or blood pressure reading. These programs must always offer a “reasonable alternative standard” for individuals for whom it is medically inadvisable or unreasonably difficult to meet the primary standard.

The “reasonably Designed” Standard

Beyond the financial incentive limits, the ADA and HIPAA introduce another crucial concept ∞ the program must be “reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease.” This standard ensures that the wellness program is a genuine health initiative and not simply a way to shift costs to employees with health problems or to unlawfully gather medical data.

A program is considered reasonably designed if it has a reasonable chance of improving health or preventing disease, is not overly burdensome, and is not a subterfuge for discrimination. For instance, a program that consists solely of a health risk assessment with no follow-up information or support would likely not be considered reasonably designed.

It must provide feedback, resources, or counseling to help employees act on the information they receive. This requirement acts as a safeguard, ensuring that if you are incentivized to provide your health data, it is for a legitimate, health-promoting purpose.

| Feature | Participatory Programs | Health-Contingent Programs |

|---|---|---|

| Requirement | Participation in an activity | Meeting a health-related standard |

| Incentive Limit (ACA/HIPAA) | Generally not subject to the 30% limit unless part of a group health plan | 30% of total cost of self-only coverage (50% for tobacco programs) |

| ADA Voluntariness | Applies if medical questions are asked or exams required (30% incentive limit under former EEOC rule) | Applies if medical questions are asked or exams required (30% incentive limit under former EEOC rule) |

| Reasonable Alternative Standard | Not required | Required for outcome-based programs |

Academic

The Jurisprudence of Voluntariness after AARP V EEOC

The legal architecture governing wellness program incentives is a product of tension between distinct legislative mandates. The ACA sought to leverage financial incentives to promote public health objectives, codifying a 30% incentive limit as a primary tool.

Concurrently, the ADA and GINA, as enforced by the EEOC, are oriented toward protecting individuals from discriminatory practices and ensuring that any disclosure of health information is genuinely voluntary. This tension culminated in the legal challenge AARP v. EEOC (2017), which vacated the EEOC’s 2016 regulations that had aligned the ADA’s incentive limit with the ACA’s 30% threshold.

The D.C. District Court’s decision was a critical inflection point, finding that the EEOC had failed to provide a reasoned explanation for why a 30% incentive level did not render a program involuntary under the ADA. The court reasoned that the agency had not supplied sufficient evidence or analysis to justify its conclusion that such a substantial incentive would not be coercive for many employees.

The vacatur of the EEOC’s rules has created a state of significant legal uncertainty. Employers are left to navigate a landscape where the ACA explicitly permits a 30% incentive for health-contingent programs tied to a health plan, while the ADA’s definition of “voluntary” for programs involving medical inquiries lacks a clear, quantified safe harbor.

This legal vacuum forces a more fundamental, qualitative analysis of voluntariness. The inquiry shifts from a simple percentage-based calculation to a more nuanced, fact-specific assessment of whether the program, in its totality, is coercive. Factors such as the size of the incentive relative to employee income, the nature of the information being requested, and the availability of reasonable alternatives become paramount.

This situation underscores a deep philosophical divide in regulatory approaches ∞ one based on population-level behavioral economics (the ACA) and another centered on individual rights and the prevention of undue influence (the ADA).

What Is the True Meaning of a Reasonably Designed Program?

The requirement that a wellness program be “reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease” serves as a critical, albeit ambiguous, bulwark against discriminatory program design. This standard demands that the program is more than a data-extraction mechanism or a cost-shifting tool.

From a systems-biology perspective, a truly “reasonably designed” program would acknowledge the heterogeneity of human physiology. It would move beyond simplistic, population-based metrics (like BMI) that may be clinically inappropriate for certain individuals due to endocrine disorders, metabolic conditions, or genetic predispositions.

For example, an outcome-based program focused on weight loss could be physiologically detrimental for an individual with hypothyroidism or polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), making the incentive to participate in such a program inherently coercive from a clinical standpoint.

A sophisticated interpretation of the “reasonably designed” standard would necessitate a personalized approach. This could involve offering a wider array of reasonable alternative standards, providing access to clinical guidance to help employees choose appropriate goals, and ensuring robust privacy protections for the sensitive data collected.

The legal standard, therefore, can be seen as implicitly advocating for a more clinically-informed and ethically sound program architecture. It pushes beyond a mere checklist of activities and toward a model that respects individual biological variance and promotes health in a meaningful, non-punitive manner.

A program’s design must be clinically valid and non-coercive to meet the legal standard of being “reasonably designed.”

| Action | Year | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| HIPAA Final Rules | 2006 | Established initial framework for wellness programs and a 20% incentive limit. |

| Affordable Care Act (ACA) | 2010 | Increased the maximum incentive to 30% (50% for tobacco) for health-contingent programs. |

| EEOC Final Rules (ADA & GINA) | 2016 | Aligned ADA/GINA incentive limits with the ACA’s 30% cap for programs with medical inquiries. |

| AARP v. EEOC | 2017 | Vacated the EEOC’s 2016 rules, removing the 30% safe harbor under the ADA and creating legal uncertainty. |

The Intersection of Privacy and Autonomy

The collection of employee health data through wellness programs raises profound questions at the intersection of privacy, autonomy, and data ethics. While HIPAA provides a robust framework for protecting identifiable health information within the healthcare system, the protections for data collected by employer-sponsored wellness programs can be less clear, particularly for programs administered by third-party vendors.

The voluntariness of participation is inextricably linked to an employee’s understanding of how their data will be used, stored, and protected. An incentive might persuade an employee to share information they would otherwise keep private. This exchange is only truly voluntary if the employee can provide informed consent, which requires transparent communication about the program’s data privacy and security practices.

The legal framework, therefore, must be understood not just as a set of rules about financial incentives, but as a system that attempts to preserve the conditions necessary for autonomous decision-making in an environment of inherent power imbalance.

The ongoing legal and regulatory debate reflects a societal effort to define the appropriate boundaries of corporate involvement in employee health in an era of big data. The ultimate resolution will likely require a more integrated approach that harmonizes the behavioral economic goals of the ACA with the individual rights protections of the ADA, ensuring that programs are not only “reasonably designed” from a clinical perspective but also from a data privacy and ethical standpoint.

References

- “Workplace Wellness Programs Characteristics and Requirements.” KFF, 19 May 2016.

- “Guide to Understanding Wellness Programs and their Legal Requirements.” Acadia Benefits, May 2016.

- “What do HIPAA, ADA, and GINA Say About Wellness Programs and Incentives?” WellSteps.

- “EEOC Proposes Rule Related to Employer Wellness Programs.” CDF Labor Law LLP, 20 Apr. 2015.

- “2024 Newfront Wellness Program Guide.” Newfront.

Reflection

Reclaiming Your Health Narrative

The knowledge of these legal frameworks serves a purpose far beyond academic understanding. It is a tool for self-advocacy. Your health journey is a deeply personal narrative, shaped by your unique biology, experiences, and choices. When external pressures, such as financial incentives, enter that narrative, it is essential to have a clear understanding of the boundaries that exist to protect your autonomy.

The information presented here is designed to be a starting point for your own introspection. How do you define voluntary participation in your own life? What level of incentive feels like a genuine choice, and at what point does it feel like a mandate?

Contemplating these questions empowers you to engage with workplace wellness initiatives from a position of strength and awareness. Your health is your greatest asset, and the decisions you make about it should be yours alone, guided by credible information and your own internal compass.