Fundamentals

You have arrived here seeking clarity on a complex subject, likely because you are navigating the world of corporate wellness programs and feeling a sense of unease. You may be asking yourself what your employer can and cannot ask of you, what information is being collected, and for what purpose.

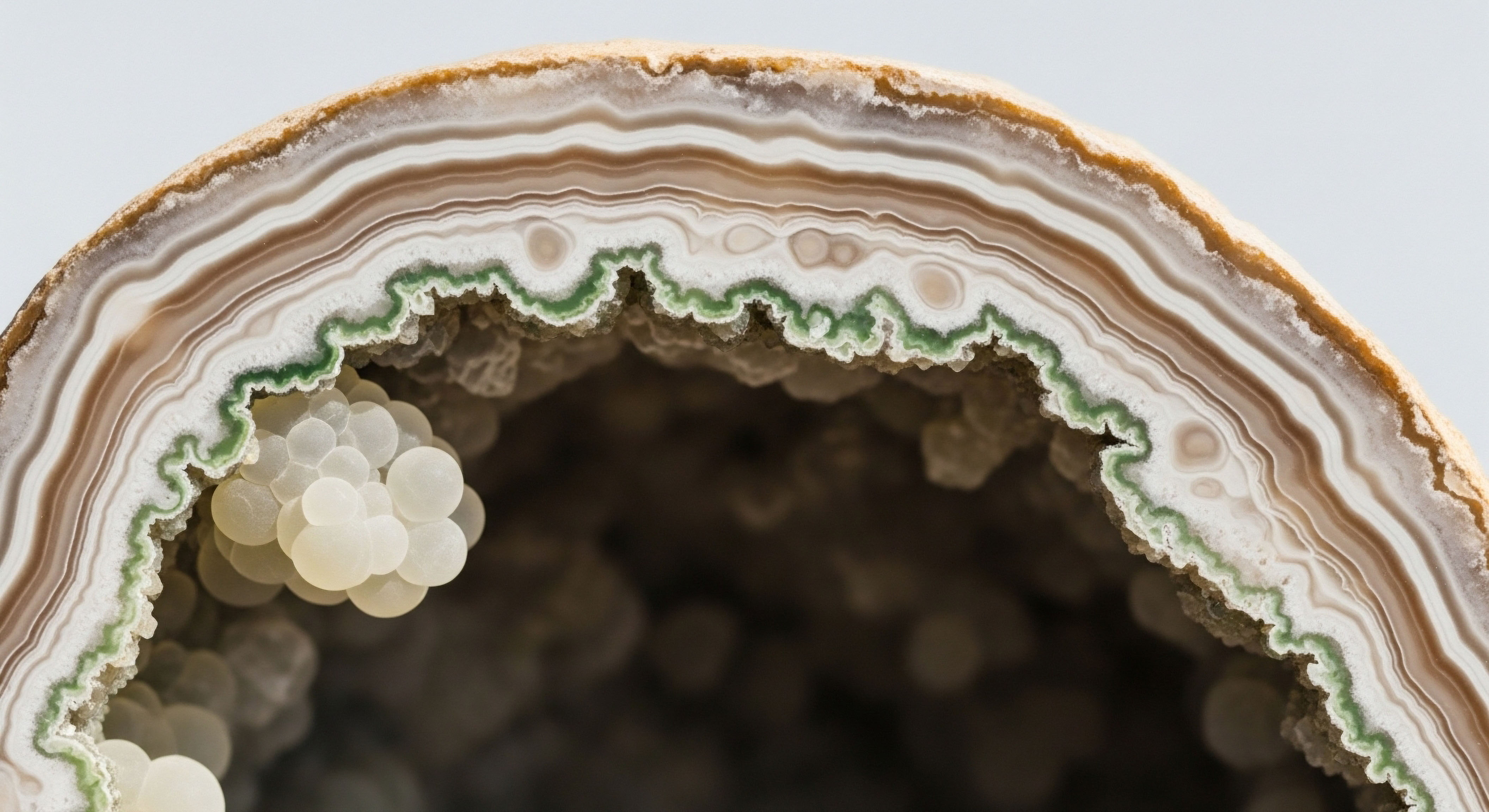

This is a valid and important line of inquiry. Your health data is profoundly personal, a blueprint of your internal world. Understanding the rules that govern its use is the first step toward reclaiming agency in your own wellness journey. We will explore the distinctions between the HIPAA Safe Harbor and the ADA’s rules for wellness incentives, and in doing so, we will begin a much larger and more significant exploration of your own biology.

The journey into your own health is a personal one. It begins with data. Your symptoms, your energy levels, your sleep quality ∞ these are all data points. A wellness program, with its biometric screenings and health risk assessments, can provide additional data.

The legal frameworks of HIPAA and the ADA are designed to create a protected space for this data collection. They are the guardrails intended to ensure that your participation in a wellness program is a choice, not a mandate, and that the information you share is used to support your health, not to penalize you.

What Is the Core Purpose of These Regulations?

At their heart, both HIPAA and the ADA are civil rights laws. They are designed to protect you from discrimination. HIPAA, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, is broadly concerned with the privacy and security of your protected health information (PHI). It establishes national standards to prevent the unauthorized disclosure of your health data.

The HIPAA Safe Harbor for wellness programs is a specific provision within this larger framework. It allows employers to offer financial incentives for participation in wellness programs without violating HIPAA’s nondiscrimination rules. This safe harbor is what permits your employer to offer a discount on your health insurance premiums for completing a health risk assessment, for example.

The Americans with Disabilities Act, or ADA, has a different primary focus. It prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities in all areas of public life, including employment. In the context of wellness programs, the ADA is concerned with ensuring that these programs are voluntary and do not discriminate against employees with disabilities.

This is particularly relevant when a wellness program includes medical examinations or asks questions about your health history, which could reveal a disability. The ADA’s rules for wellness incentives are designed to ensure that the financial incentives are not so large as to be coercive, effectively forcing employees to disclose their health information.

Understanding these regulations is the first step toward using wellness programs as a tool for personal health discovery, rather than seeing them as an intrusive employer requirement.

The tension between these two laws arises from their different approaches to incentive limits. HIPAA, as amended by the Affordable Care Act (ACA), allows for more substantial incentives, particularly for programs that target specific health outcomes like smoking cessation.

The ADA, as interpreted by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), has historically favored lower incentive limits to ensure that participation remains truly voluntary. This is where the confusion often lies for both employers and employees. The legal landscape is a patchwork of overlapping regulations, and navigating it requires a clear understanding of the intent behind each law.

From a clinical perspective, the data collected by these programs can be the start of a conversation with your own body. The numbers on a biometric screening ∞ your blood pressure, your cholesterol levels, your blood sugar ∞ are clues to the state of your internal environment.

They can point to underlying imbalances in your endocrine system, the intricate network of glands and hormones that governs everything from your metabolism to your mood. By understanding the legal protections in place, you can approach these programs with a sense of empowerment, knowing that you are in control of your data and can use it to begin a journey of profound self-knowledge and healing.

Intermediate

As we move beyond the foundational principles of HIPAA and the ADA, we begin to see how their differences manifest in the design of workplace wellness programs. The distinction between “participatory” and “health-contingent” programs is central to this understanding.

This is where the legal framework directly intersects with your personal health journey, as the type of program your employer offers will determine the nature of your engagement and the data you are asked to provide. A participatory program is one in which you are rewarded simply for participating, without any requirement to achieve a specific health outcome.

An example would be receiving an incentive for completing a health risk assessment or attending a seminar on nutrition. These programs are generally subject to fewer regulations under HIPAA.

Health-contingent programs, on the other hand, require you to meet a specific health-related standard to earn an incentive. These programs are further divided into two categories ∞ activity-only and outcome-based. An activity-only program requires you to perform a specific activity, such as walking a certain number of steps per day, but you do not have to achieve a specific health outcome.

An outcome-based program requires you to achieve a specific health outcome, such as lowering your cholesterol or blood pressure to a certain level. It is in the realm of health-contingent programs that the differences between the HIPAA Safe Harbor and the ADA’s rules become most apparent.

How Do Incentive Limits Differ in Practice?

The HIPAA Safe Harbor, as expanded by the ACA, provides clear guidelines for the maximum incentive that can be offered for health-contingent wellness programs. Generally, the total incentive is limited to 30% of the total cost of employee-only health coverage. This limit can be increased to 50% for programs designed to prevent or reduce tobacco use.

The rationale behind these limits is to encourage participation in programs that can lead to improved health outcomes and lower healthcare costs, while still providing a degree of protection against overly coercive incentives. From a clinical standpoint, this is a recognition that lifestyle modifications, such as quitting smoking or improving metabolic markers, can have a profound impact on long-term health.

The ADA’s rules on wellness incentives have been a source of considerable debate and legal challenges. The EEOC, the agency responsible for enforcing the ADA, has expressed concern that large incentives could make participation in a wellness program involuntary for many employees, effectively forcing them to disclose disability-related information.

While the ADA itself has a “safe harbor” for bona fide benefit plans, the EEOC has historically argued that this safe harbor does not apply to most employer wellness programs. This has led to a situation where a wellness program could be in compliance with HIPAA’s incentive limits but potentially in violation of the ADA.

The EEOC’s position has been that any medical inquiries or examinations in a wellness program must be part of a “voluntary” program, and the size of the incentive is a key factor in determining voluntariness.

The practical result of these differing regulations is a complex compliance landscape for employers and a source of potential confusion for employees seeking to understand their rights.

To navigate this complexity, it is helpful to understand the concept of “reasonable alternatives.” Both HIPAA and the ADA require that health-contingent wellness programs offer a reasonable alternative standard for individuals for whom it is medically inadvisable or unreasonably difficult to meet the initial standard.

For example, if a program rewards employees for achieving a certain BMI, an individual with a medical condition that makes weight loss difficult must be offered an alternative way to earn the reward, such as participating in a nutrition counseling program.

This requirement is a crucial protection, as it acknowledges that health is not a one-size-fits-all proposition. From a physiological perspective, this is a nod to the reality of bio-individuality. Your unique genetic makeup, your hormonal profile, and your life circumstances all play a role in your health outcomes.

The following table provides a simplified comparison of the key provisions of the HIPAA Safe Harbor and the ADA’s rules for wellness incentives:

| Feature | HIPAA Safe Harbor (as per ACA) | ADA Rules (as per EEOC Interpretation) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Nondiscrimination in health coverage based on health factors. | Nondiscrimination against individuals with disabilities. |

| Incentive Limit (General) | Up to 30% of the cost of employee-only health coverage. | Historically, the EEOC has favored lower limits to ensure voluntariness, but recent proposed rules have moved toward harmonization with HIPAA. |

| Incentive Limit (Tobacco Cessation) | Up to 50% of the cost of employee-only health coverage. | The 30% limit may still apply if the program requires a medical test for nicotine. |

| Application of “Safe Harbor” | The HIPAA Safe Harbor specifically applies to wellness programs that meet its criteria. | The EEOC has historically rejected the application of the ADA’s “bona fide benefit plan” safe harbor to most wellness programs. |

| Requirement for Reasonable Alternatives | Required for all health-contingent wellness programs. | Required to provide a reasonable accommodation for individuals with disabilities. |

This legal framework, while complex, provides a starting point for a deeper inquiry into your own health. If a wellness program screening reveals that your blood sugar is elevated, for example, this is an opportunity to look beyond the number and explore the underlying metabolic processes.

This could lead you to investigate the role of insulin, the impact of chronic stress on cortisol levels, and the intricate dance of hormones that regulates your energy and metabolism. The law provides the container; your curiosity and desire for well-being provide the content.

Academic

The intersection of the HIPAA Safe Harbor and the ADA’s regulations for wellness programs creates a fascinating case study in the challenges of applying legal frameworks to the dynamic and deeply personal domain of human health. A particularly compelling area of inquiry is the ADA’s “subterfuge” clause.

The ADA’s safe harbor provision for bona fide benefit plans states that the safe harbor cannot be used as a “subterfuge to evade the purposes of this chapter.” This raises a profound question ∞ could a wellness program that is technically compliant with incentive limits still be considered a subterfuge if its design is fundamentally at odds with established principles of endocrinology and metabolic health? This is where a “Clinical Translator” perspective becomes essential to bridge the gap between legal theory and biological reality.

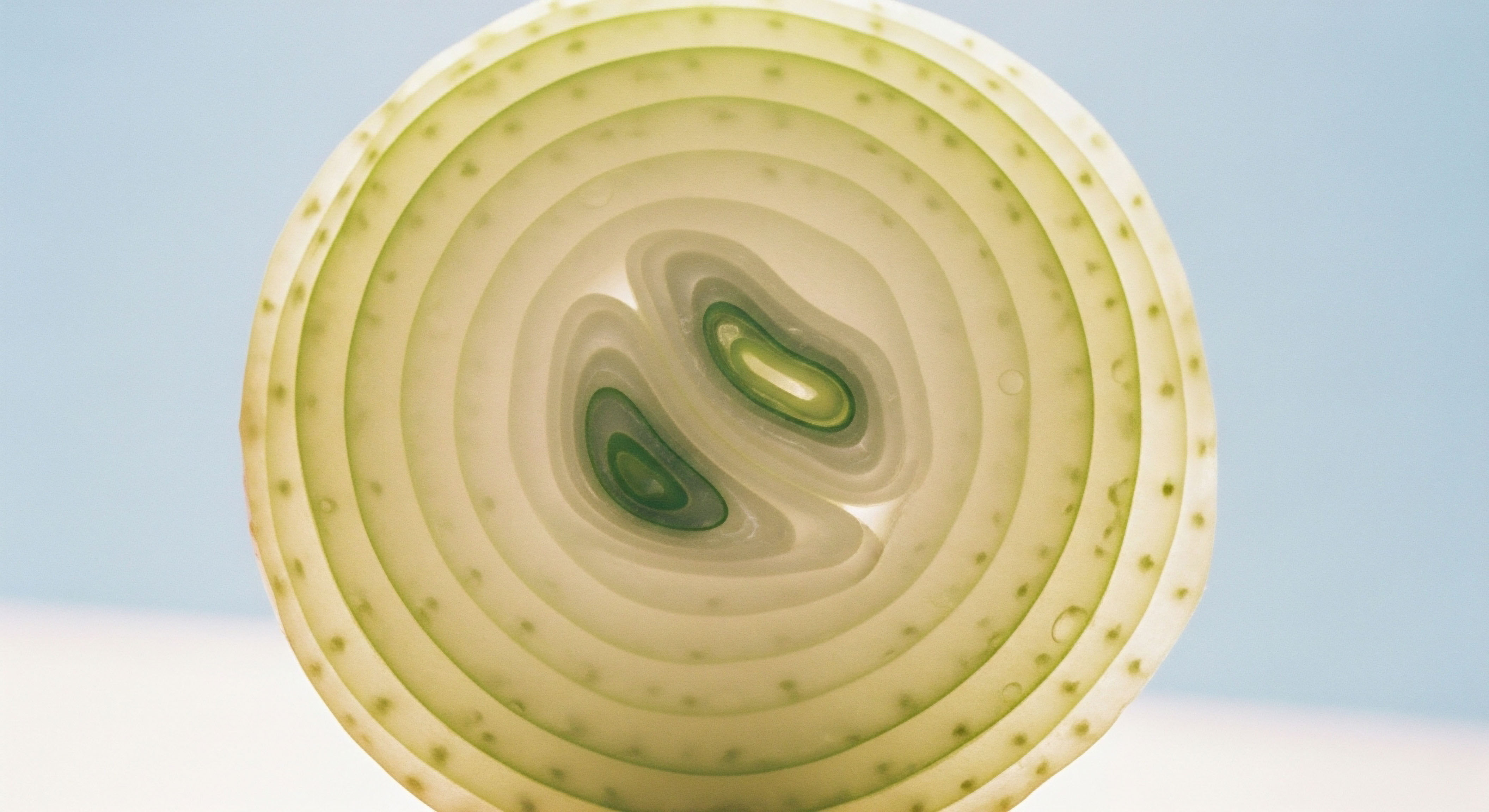

Consider a common feature of many wellness programs ∞ a focus on Body Mass Index (BMI) as a key metric for health. An outcome-based program might offer a significant financial incentive to employees who achieve a BMI within the “normal” range. On the surface, this may seem like a reasonable, data-driven approach to promoting health.

However, from a sophisticated clinical perspective, a rigid focus on BMI is a crude and often misleading measure of health. BMI is a simple calculation of weight to height, and it fails to account for body composition. An individual with a high degree of muscle mass and low body fat could be classified as “overweight” or “obese” by BMI standards.

Conversely, an individual with a “normal” BMI could have a high percentage of visceral fat, the metabolically active fat that surrounds the organs and is a significant driver of inflammation and insulin resistance. This condition, often referred to as “normal weight obesity,” is a serious health risk that is completely invisible to a BMI-based screening.

Can a Wellness Program’s Design Constitute a Form of Discrimination?

Herein lies the potential for subterfuge. A wellness program that penalizes an individual for having a high BMI, without offering a more sophisticated analysis of body composition or considering the individual’s underlying hormonal profile, could be seen as a form of discrimination disguised as a health initiative.

This is particularly true for individuals with certain endocrine disorders. For example, individuals with hypothyroidism or Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) often experience significant challenges with weight management that are directly related to their hormonal imbalances.

To penalize such an individual for failing to meet a generic BMI target, without providing a reasonable and clinically relevant alternative, could be argued as a violation of the spirit, if not the letter, of the ADA. The program, in this case, would be using a flawed metric to create a barrier to reward, a barrier that disproportionately affects individuals with certain medical conditions, which may qualify as disabilities under the ADA.

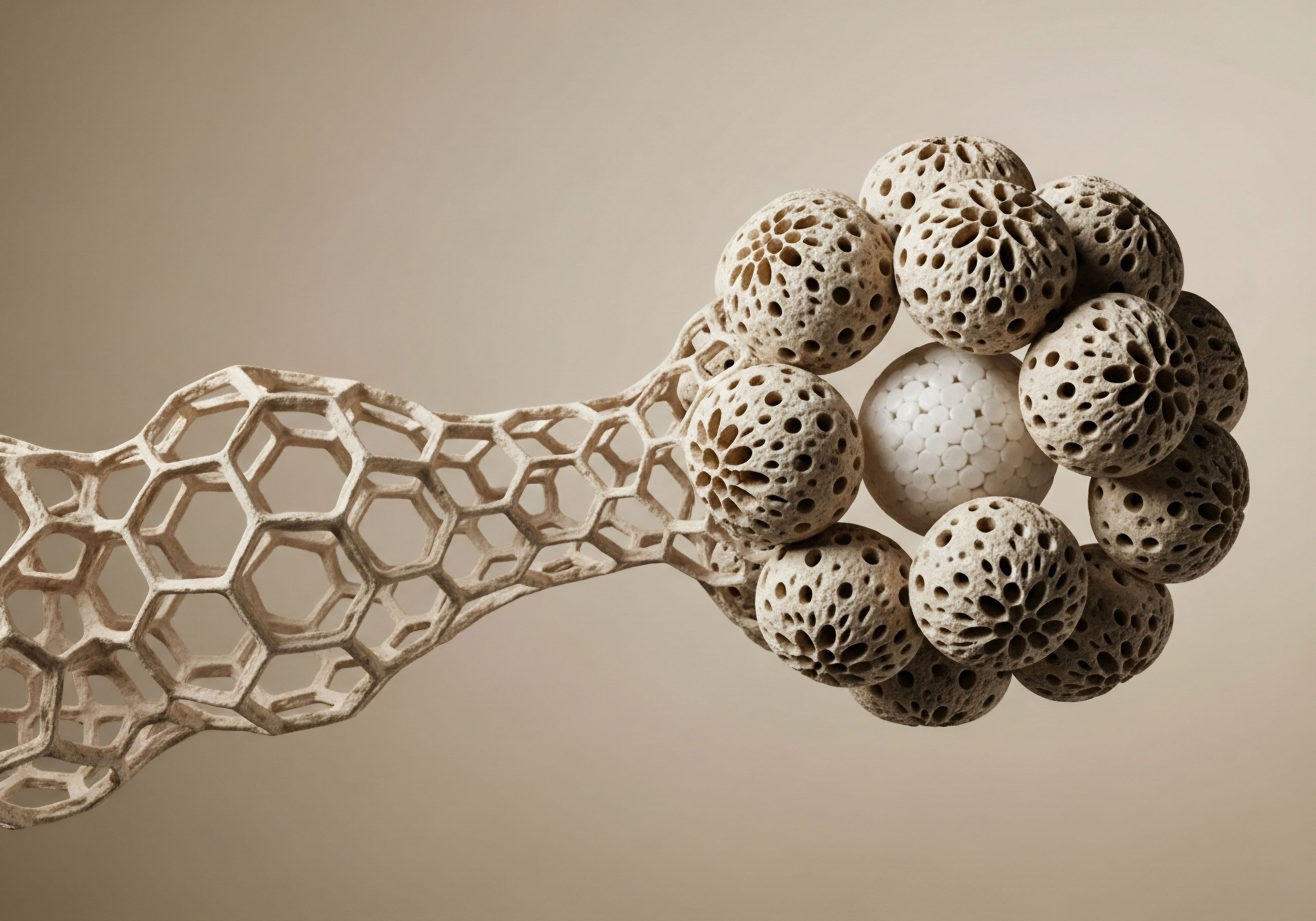

The concept of “risk assessment,” which is central to the ADA’s safe harbor, also merits a deeper, more critical examination. The purpose of the safe harbor is to permit the “underwriting, classifying, or administering of risks.” A simplistic wellness program might classify risk based on a handful of biometric data points.

A more sophisticated, clinically-informed approach to risk assessment would recognize that an individual’s health risk is a complex and dynamic interplay of genetics, lifestyle, and environment. It would look beyond simple biomarkers to understand the functioning of the body’s key regulatory systems, such as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis.

A truly effective wellness program would move beyond simplistic metrics and embrace a more personalized, systems-based approach to health, one that acknowledges the profound influence of the endocrine system.

The HPA axis, for example, is the body’s central stress response system. Chronic stress, a common feature of modern life and many work environments, can lead to HPA axis dysregulation, resulting in chronically elevated cortisol levels. This, in turn, can contribute to a host of health problems, including insulin resistance, visceral fat accumulation, hypertension, and immune suppression.

A wellness program that fails to account for the impact of stress on health, or worse, that adds to an employee’s stress by imposing unrealistic health targets, is not engaging in a legitimate form of risk assessment. It is, in effect, ignoring a key driver of disease and potentially exacerbating the very problems it claims to be addressing.

The following table outlines some of the key differences between a simplistic, potentially discriminatory wellness program and a more sophisticated, clinically-informed model:

| Feature | Simplistic Wellness Program | Clinically-Informed Wellness Program |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Metric | Body Mass Index (BMI) | Body composition analysis, waist-to-hip ratio, and a panel of metabolic markers. |

| Risk Assessment | Based on a few isolated biometric data points. | Holistic assessment that considers the interplay of hormonal systems (HPA, HPG, thyroid), lifestyle factors, and genetics. |

| Approach to “Unhealthy” Markers | Penalizes failure to meet generic targets. | Uses data as a starting point for further investigation and personalized intervention. |

| Reasonable Alternatives | Offers generic alternatives, such as attending a class. | Offers clinically relevant alternatives, such as advanced hormonal testing, consultation with an endocrinologist, or personalized nutrition and exercise plans based on individual physiology. |

Ultimately, a wellness program that is truly designed to “promote health or prevent disease,” as the ADA requires, must be built on a foundation of sound scientific principles. It must recognize the complexity and individuality of human biology.

A program that relies on outdated or overly simplistic metrics, and that fails to provide meaningful and accessible pathways for individuals to address the root causes of their health issues, runs the risk of becoming a tool of discrimination rather than an instrument of well-being.

The ongoing dialogue between the courts, the EEOC, and public health advocates about the proper application of the ADA to wellness programs is a reflection of this fundamental tension. It is a debate about whether these programs will be designed to truly support the diverse and complex health needs of all employees, or whether they will become another form of subterfuge, a way of shifting costs and responsibilities under the guise of promoting health.

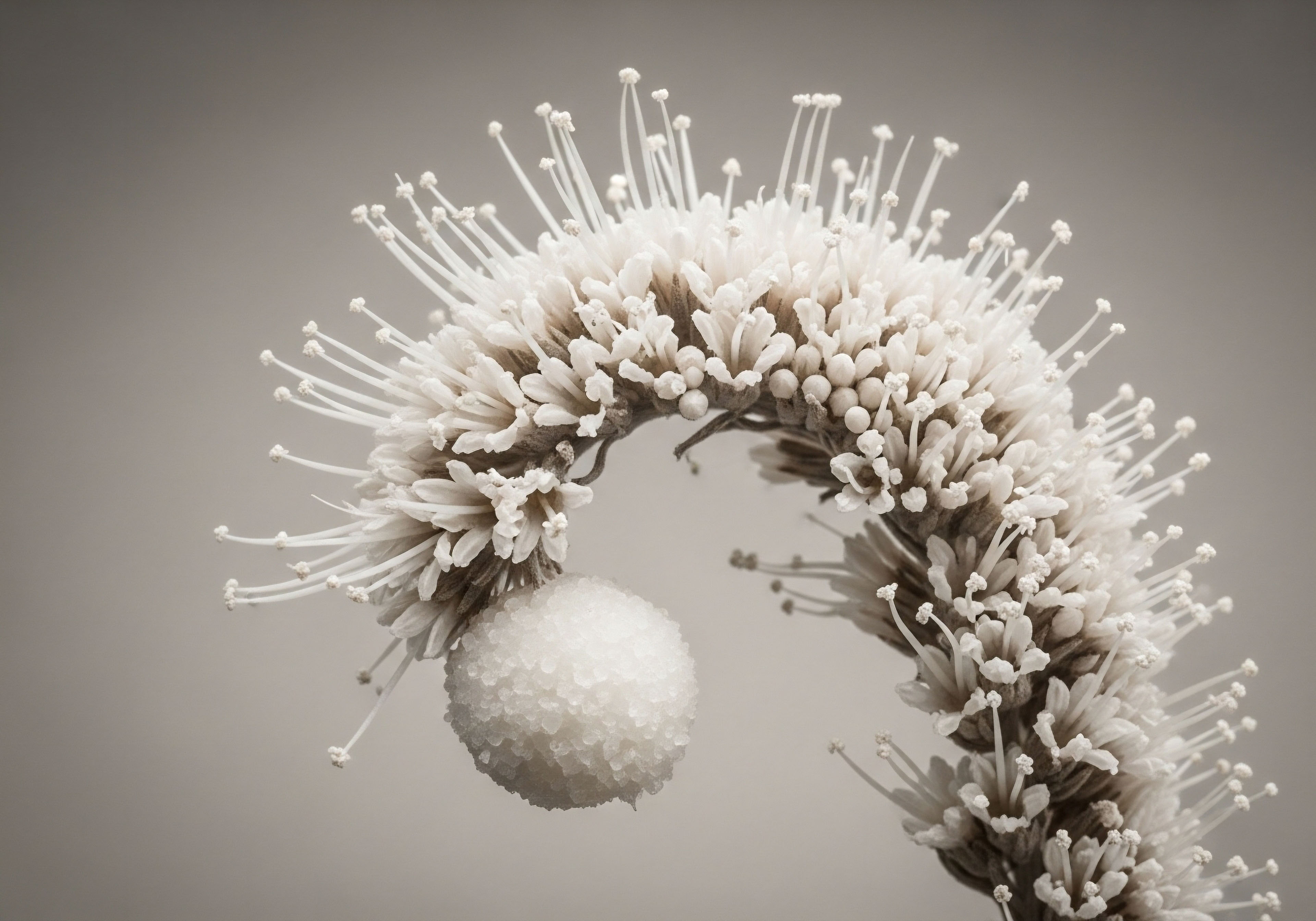

- Hormonal Context ∞ The regulations must be interpreted through the lens of endocrinology. A person’s ability to meet a wellness program’s targets is profoundly influenced by their hormonal status. For example, insulin resistance, a key driver of metabolic disease, is a hormonal condition. A program that ignores this reality is not truly “reasonably designed.”

- The Role of Genetics ∞ The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) adds another layer of complexity. It prohibits discrimination based on genetic information in both health insurance and employment. As our understanding of the genetic basis of disease grows, wellness programs will need to be carefully designed to avoid using genetic information in a discriminatory manner. For example, a program that screens for genetic markers associated with a higher risk of certain diseases and then uses that information to set health targets could be in violation of GINA.

- Personalized Medicine as the Future ∞ The limitations of the current wellness program model point to the need for a more personalized approach to health. The future of wellness is not in one-size-fits-all programs, but in individualized protocols based on a deep understanding of a person’s unique biology. This is where advanced diagnostics, such as comprehensive hormonal panels, genetic testing, and continuous glucose monitoring, can play a transformative role. These tools, which are central to the practice of personalized and longevity medicine, provide a much richer and more accurate picture of an individual’s health than a simple biometric screening.

The legal frameworks of HIPAA and the ADA will need to evolve to keep pace with these scientific advancements. The challenge will be to create a regulatory environment that both protects individuals from discrimination and encourages the responsible use of new technologies to promote genuine health and well-being.

For the individual, the journey begins with the recognition that you are the foremost expert on your own body. The data from a wellness program, the guidance of a knowledgeable clinician, and the legal protections afforded by laws like HIPAA and the ADA are all tools to be used in the service of your own health optimization.

References

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. “Proposed Rule on Wellness Programs.” Federal Register, vol. 86, no. 10, 15 Jan. 2021, pp. 3961-3985.

- “Final Rule on Employer Wellness Programs and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act.” Federal Register, vol. 81, no. 95, 17 May 2016, pp. 31143-31156.

- Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, 42 U.S.C. § 12201(c).

- “Final Rules for Nondiscrimination in Health Coverage in the Group Market.” Federal Register, vol. 78, no. 106, 3 June 2013, pp. 33158-33209.

- Seff v. Broward County, 691 F.3d 1221 (11th Cir. 2012).

- Black & Decker Disability Plan v. Nord, 538 U.S. 822 (2003).

- Guyton, A.C. & Hall, J.E. (2020). Textbook of Medical Physiology. 14th ed. Elsevier.

- Boron, W.F. & Boulpaep, E.L. (2016). Medical Physiology. 3rd ed. Elsevier.

- Rosen, C.J. (2020). “The 2019 Endocrine Society Practice Guideline on Pharmacological Management of Osteoporosis in Postmenopausal Women ∞ A Review.” JAMA, 323(12), pp.1184-1187.

- Bhasin, S. et al. (2018). “Testosterone Therapy in Men With Hypogonadism ∞ An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 103(5), pp. 1715-1744.

Reflection

You began this exploration seeking to understand the boundaries drawn by laws and regulations. You now possess a map of that complex terrain. Yet, the most significant territory remains to be explored, the one that lies within you.

The true value of this knowledge is not in understanding the limits of what an employer can ask, but in recognizing the limitless potential of what you can ask of yourself. The data points from a wellness screening, the numbers on a lab report, these are not judgments. They are signposts, pointing toward a deeper conversation with your own physiology.

What if you were to view every piece of health information not as a score to be judged, but as a message to be decoded? What if the fatigue you feel is not a personal failing, but a signal from your adrenal glands?

What if the difficulty in maintaining a healthy weight is not a lack of willpower, but a complex hormonal conversation involving your thyroid, insulin, and leptin? The journey from feeling unwell to reclaiming your vitality begins with this shift in perspective. It begins with the courage to ask “why” and the determination to seek out answers that resonate with your unique biology.

The path forward is a personal one. It is a process of assembling your own team of trusted advisors, of seeking out knowledge from sources that honor the complexity of the human body, and of learning to listen to the subtle whispers of your own internal systems before they become screams.

The information you have gained here is a tool, a powerful one, but a tool nonetheless. The true work, the deeply rewarding work of building a life of vibrant health, is now in your hands. What will you build?

Glossary

wellness programs

wellness incentives

hipaa safe harbor

wellness program

protected health information

risk assessment

safe harbor

against individuals with disabilities

americans with disabilities act

health information

incentive limits

equal employment opportunity commission

endocrine system

specific health outcome

health-contingent wellness programs

employee-only health coverage

bona fide benefit plans

health-contingent wellness

wellness program that

bona fide benefit

hpa axis

genetic information nondiscrimination act