Fundamentals

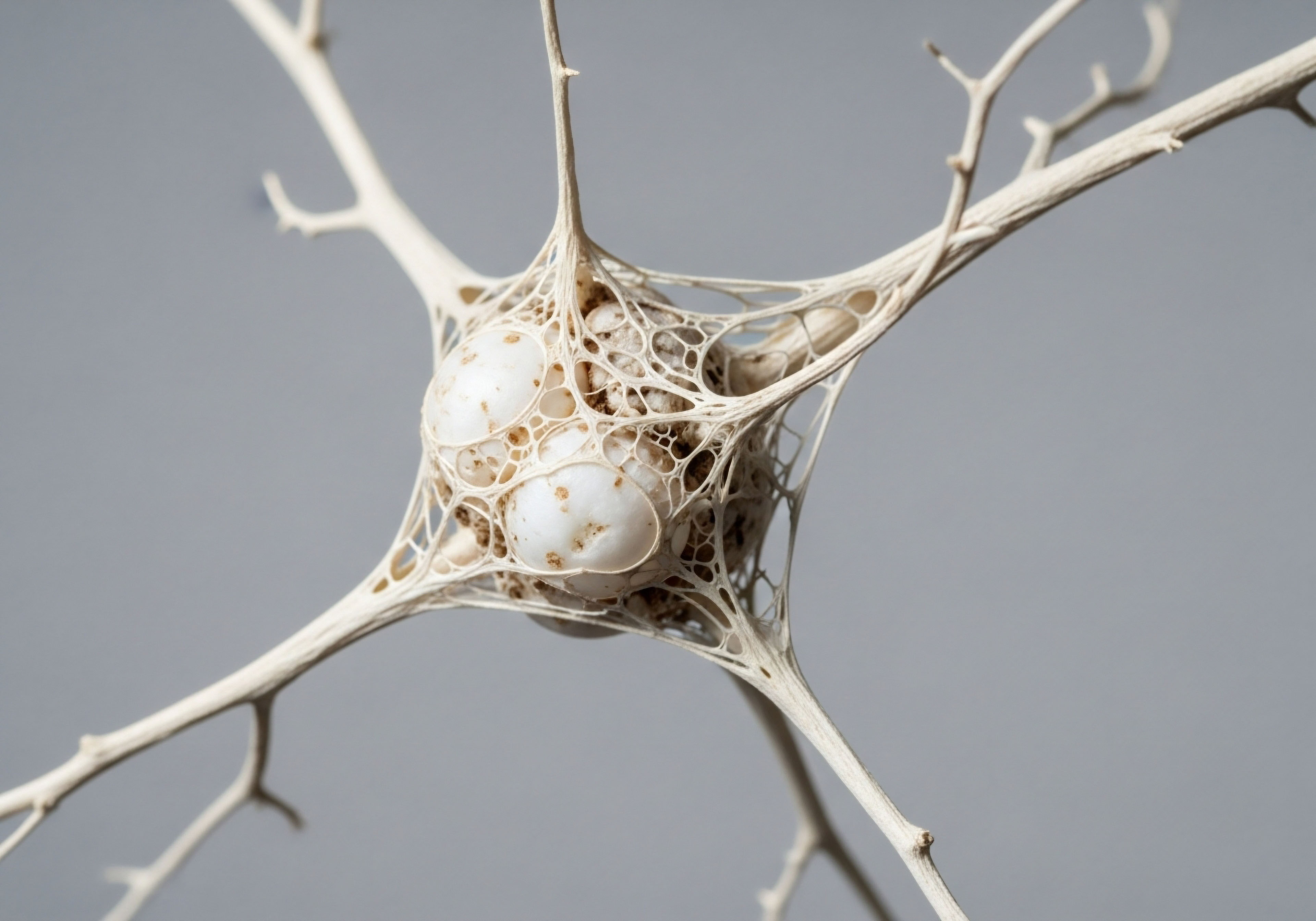

Your health is a deeply personal affair. It is a complex, dynamic system of information flowing through your body, a conversation between your genes and your environment. When an employer offers a wellness program, it asks to be let into that conversation.

It seeks access to your personal health information with the stated goal of helping you improve your well-being. This invitation brings with it a web of legal and ethical considerations, governed by a trio of federal laws ∞ the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA), and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Understanding these laws is the first step in navigating the landscape of corporate wellness with confidence and clarity.

Imagine you are an employee, and your company introduces a new, voluntary wellness initiative. The program offers a discount on your health insurance premiums if you complete a Health Risk Assessment (HRA) and undergo biometric screening. Your decision to participate involves more than a simple cost-benefit analysis; it requires an understanding of your rights. Each of these laws provides a distinct layer of protection, forming a shield to protect your most sensitive data.

The Americans with Disabilities Act a Foundation of Equal Opportunity

The Americans with Disabilities Act is a landmark civil rights law. Its core purpose is to prohibit discrimination against individuals with disabilities in all areas of public life, including employment. In the context of a wellness program, the ADA’s protections are triggered the moment a program asks questions about your health or requires a medical examination, such as a blood draw or blood pressure screening. These are known as “disability-related inquiries” and “medical examinations.”

The law generally forbids employers from making such inquiries unless they are job-related and consistent with business necessity. There is a specific exception for voluntary employee health programs. The term “voluntary” is the key. For a program to be considered voluntary under the ADA, your employer cannot require you to participate.

They cannot deny you health coverage or take any adverse employment action if you choose not to answer the health questions or take the medical exam. The law seeks to ensure that your participation is a genuine choice, free from coercion or undue pressure. This principle of voluntary participation is the ADA’s primary contribution to the wellness program framework, ensuring that access to health benefits is available to all qualified employees, regardless of disability.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act a Guardian of Privacy

HIPAA is most widely known for its Privacy Rule, which establishes national standards to protect individuals’ medical records and other identifiable health information. This information is referred to as Protected Health Information (PHI). HIPAA’s rules apply to “covered entities,” which include health plans, health care clearinghouses, and most health care providers.

A critical point of understanding is that HIPAA’s direct authority over an employer is limited. The law primarily governs how health plans, including the one your employer sponsors, can use and disclose your health information.

If your company’s wellness program is part of its group health plan, HIPAA’s regulations apply directly. The law allows for the creation of wellness programs and even permits incentives for participation. It establishes two categories of wellness programs:

- Participatory Programs ∞ These programs reward participation alone, without requiring an individual to meet a specific health standard. An example is a program that offers a reward for simply completing a Health Risk Assessment.

- Health-Contingent Programs ∞ These programs require individuals to meet a specific health-related goal to obtain a reward. This could involve achieving a certain cholesterol level or quitting smoking. These programs are subject to stricter rules to prevent discrimination.

HIPAA’s main function within this legal triad is to secure your data. It dictates that personally identifiable health information sent to a health plan or its vendors cannot be shared with your employer for discriminatory purposes, such as in hiring or firing decisions. Information provided to the employer must be in an aggregated format that does not identify individuals.

The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act a Shield for Your Blueprint

GINA is the most targeted of the three laws. It was enacted to address concerns that the advancements in genetics could be used by employers and insurers to discriminate against individuals based on their genetic predispositions to disease. The law has two main parts, Title I, which applies to health insurers, and Title II, which applies to employers.

The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act protects individuals from discrimination based on their genetic makeup in both health insurance and employment contexts.

Genetic information is defined broadly under GINA. It includes information about an individual’s genetic tests, the genetic tests of family members, and the manifestation of a disease or disorder in family members (i.e. your family medical history). A wellness program that asks you to complete an HRA and includes questions about your family’s health history is requesting genetic information, thereby activating GINA’s protections.

Similar to the ADA, GINA prohibits employers from requesting, requiring, or purchasing genetic information. It also contains an exception for voluntary wellness programs. For the collection of genetic information to be permissible, you must provide prior, knowing, and written authorization. A crucial stipulation is that any financial incentive offered cannot be conditioned on you providing this genetic information.

Your employer can reward you for completing the HRA, but they cannot offer a greater reward to employees who also provide their family medical history. This provision ensures that you are not financially pressured into revealing information that could be used to predict your future health risks.

Intermediate

The relationship between the ADA, GINA, and HIPAA is one of overlapping jurisdiction and, at times, regulatory tension. These laws were not written as a single, cohesive code. They were enacted at different times to address distinct concerns, yet they converge on the modern workplace wellness program. The result is a complex regulatory environment where compliance requires navigating the subtle interplay of their different standards, particularly concerning the definition of “voluntary” participation and the limits on financial incentives.

The central conflict has historically revolved around the size of the incentive an employer can offer. A large enough incentive can be perceived as coercive, rendering a program involuntary in practice, even if it is labeled otherwise.

The government agencies responsible for enforcing these laws, primarily the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) for the ADA and GINA, and the Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and the Treasury for HIPAA, have worked to harmonize these rules, though this process has been fraught with legal challenges and shifting standards.

How Do the Incentive Limits Interact and Conflict?

The crux of the interaction lies in the incentive structures. HIPAA, as amended by the Affordable Care Act (ACA), set a clear financial boundary. It permitted wellness program incentives of up to 30% of the total cost of self-only health coverage (or 50% for programs designed to prevent or reduce tobacco use). From the perspective of the ACA, the goal was to encourage wellness participation, and a significant incentive was seen as an effective tool for achieving that goal.

The EEOC, however, approached the issue from a different vantage point. The agency’s mission is to prevent discrimination. It raised concerns that a 30% incentive, which could amount to thousands of dollars, might be so high as to be coercive for lower-wage workers.

An employee who cannot afford to lose that discount might feel compelled to disclose sensitive health information, thus undermining the ADA’s “voluntary” requirement. This led to a period of regulatory dissonance. In 2016, the EEOC issued rules under the ADA and GINA that also adopted the 30% incentive limit, seemingly creating a unified standard.

The core tension between these federal laws arises from their differing views on financial incentives, balancing health promotion goals against the risk of coercive data collection.

This alignment was short-lived. A lawsuit filed by the AARP (AARP v. EEOC) challenged the EEOC’s 2016 rules, arguing that the 30% limit was still too high to ensure true voluntariness. A federal court agreed, finding that the EEOC had not provided a reasoned explanation for how it determined that a 30% incentive did not act as a coercive penalty.

The court vacated the incentive limit portion of the rules, effective January 1, 2019. This decision threw the regulatory landscape back into a state of uncertainty, leaving employers without a clear, unified standard for incentive limits under all three laws.

The Current State of Voluntariness and Incentives

Following the court’s decision, employers have been navigating a more ambiguous environment. While the HIPAA incentive limits remain in place, the ADA and GINA components are less defined. In early 2021, the EEOC issued new proposed rules that signaled a significant shift in its thinking.

These proposed rules suggested that for a wellness program that is merely participatory (i.e. asks for health information but does not require meeting a health goal), only “de minimis” incentives could be offered. A de minimis incentive is a very small one, like a water bottle or a gift card of modest value.

This proposal marked a clear divergence from the HIPAA framework. The table below illustrates the differing standards under the 2016 rules and the subsequent proposed changes, highlighting the areas of convergence and divergence.

| Legal Framework | Incentive Limit for Health-Contingent Programs | Incentive Limit for Participatory Programs (with medical inquiries) | Incentive for Spousal/Family Information (GINA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIPAA/ACA | Up to 30% of cost of self-only coverage (50% for tobacco cessation) | No limit specified (as these are less regulated under HIPAA) | N/A (HIPAA does not directly govern this) |

| ADA/GINA (2016 Rules – Vacated) | Up to 30% of cost of self-only coverage | Up to 30% of cost of self-only coverage | Up to 30% of cost of self-only coverage for spousal participation |

| ADA/GINA (2021 Proposed Rules) | Up to 30% of cost of self-only coverage (aligning with HIPAA) | “De minimis” only (e.g. a water bottle) | “De minimis” only for information from family members |

Navigating the Practical Application

For an organization designing a wellness program, this complex legal environment requires a careful, multi-step analysis. The structure of the program dictates which rules are most prominent.

- Is the program part of a group health plan? If yes, HIPAA’s nondiscrimination rules and incentive limits for health-contingent programs apply from the outset.

- Does the program involve medical inquiries or exams? If yes, the ADA is triggered, and the program must be voluntary. The level of incentive offered will be a key factor in determining voluntariness.

- Does the program request genetic information (including family medical history)? If yes, GINA applies. The employer must obtain written authorization, and it cannot condition an incentive on the provision of this specific information.

Consider a program offering a premium discount for completing both a biometric screening (ADA trigger) and an HRA that asks about family history (GINA trigger). The employer must ensure that an employee who completes the screening but declines to answer the family history questions receives the same discount as an employee who completes both.

The incentive is tied to participation in the wellness activity, not to the disclosure of protected genetic information. Furthermore, the employer must provide reasonable accommodations for individuals with disabilities who may be unable to participate in the same way as other employees, such as offering an alternative way to earn the incentive.

Academic

The confluence of the ADA, GINA, and HIPAA around employer wellness programs represents a microcosm of a larger societal dialectic ∞ the tension between public health objectives and individual civil liberties. An academic analysis of this legal intersection moves beyond mere compliance to probe the jurisprudential and ethical foundations of these regulations.

The central question evolves from “What are the rules?” to “What principles do these rules seek to uphold, and how effectively do they function in a technologically advancing and data-centric economy?” The legal battles over incentive levels are a proxy for a deeper debate about the nature of consent, economic coercion, and the changing definition of privacy in the 21st century.

The Jurisprudence of Voluntariness Economic Coercion and the Reasonable Person

The legal concept of “voluntariness” is the axis upon which the entire ADA/GINA wellness framework pivots. The ADA statute provides an exception for “voluntary medical examinations. which are part of an employee health program.” The statute, however, does not define “voluntary.” This ambiguity has been the source of extensive regulatory action and litigation.

The court’s decision in AARP v. EEOC was pivotal because it rejected the EEOC’s attempt at a bright-line rule (the 30% threshold) without sufficient economic or philosophical justification. The court essentially forced the agency to confront the question ∞ at what point does a financial incentive become economically coercive, thereby rendering an employee’s choice illusory?

An analysis from a law and economics perspective suggests that the coerciveness of an incentive is not uniform. It is acutely sensitive to an employee’s income. A $1,500 premium reduction may be a modest inducement for a high-earning executive, but it can be a powerful, arguably coercive, penalty for a low-wage worker.

This raises profound questions of equity. A wellness program that is facially neutral may have a disparate impact on different segments of the workforce, creating a system where lower-income employees are disproportionately pressured into surrendering their health privacy. The EEOC’s 2021 “de minimis” proposal for participatory programs can be seen as a direct response to this critique, an attempt to sever the link between basic health data disclosure and significant financial reward.

What Is the Safe Harbor Provision and Why Does It Matter?

A deeper layer of legal complexity is introduced by the ADA’s “bona fide benefit plan safe harbor.” This provision states that the ADA’s prohibitions do not restrict an employer from establishing or observing the terms of a bona fide benefit plan, so long as the plan is not a “subterfuge” to evade the purposes of the Act.

Some employers have argued that this safe harbor allows them to design wellness programs with significant penalties for non-participation, provided the program is part of their health plan. This interpretation would effectively bypass the “voluntary” requirement for wellness programs that are integrated with insurance benefits.

The EEOC has consistently rejected this broad interpretation, arguing that the voluntary program exception is the controlling provision for wellness programs that include disability-related inquiries. The legal tension between these two statutory exceptions remains a point of contention.

A broad reading of the safe harbor could potentially swallow the voluntary rule, allowing for highly punitive wellness programs that effectively mandate health data disclosure as a condition of receiving affordable health coverage. The resolution of this issue has significant implications for the future of employee health privacy, determining whether wellness programs remain a choice or become a gatekeeper to benefits.

The unresolved legal tension between the ADA’s ‘voluntary program’ exception and its ‘bona fide benefit plan safe harbor’ is a critical fault line in employee health privacy law.

The following table outlines the competing interpretations of these key ADA provisions:

| Statutory Provision | EEOC Interpretation (Employee-Protective) | Alternative Employer Interpretation (Broad Latitude) |

|---|---|---|

| Voluntary Employee Health Program Exception | This is the primary and controlling exception for all wellness programs involving medical inquiries. The term “voluntary” must be given meaningful effect, limiting the use of large incentives. | This exception applies, but “voluntary” can be satisfied even with significant incentives, consistent with HIPAA/ACA limits. |

| Bona Fide Benefit Plan Safe Harbor | This provision is narrow. It allows for risk classification in insurance underwriting but does not permit employers to penalize employees for refusing to provide medical information to a wellness program. | This provision provides broad authority. If a wellness program is part of a health plan, its terms (including penalties) are permissible as long as they are based on underwriting risks and not intended as a subterfuge to discriminate. |

Datafication of Health and the Limits of a Siloed Legal Framework

The existing legal structure, with its three separate statutes, was designed for a world of discrete data transactions ∞ a doctor’s visit, a lab test, an insurance claim. It is increasingly ill-suited for the era of “datafication,” where continuous streams of health and wellness data are generated by wearable devices, health apps, and online platforms. These technologies blur the lines between medical data, wellness data, and lifestyle data, creating novel challenges for the ADA, GINA, and HIPAA.

For instance, can data from a smartwatch that tracks sleep patterns and heart rate variability be considered a “medical examination” under the ADA? Does an algorithm that analyzes lifestyle data to predict future health risks constitute a request for “genetic information” in a functional sense, even if it does not analyze DNA?

HIPAA’s protections may not even apply if the data is collected by a wellness vendor that is not a covered entity or a business associate of one. These technologies are creating gaps in the regulatory fabric. The siloed nature of the laws, each with its own definitions and triggers, means that vast quantities of sensitive health-adjacent information may fall outside their protective scope, leaving employees with little control over how their data is collected, used, and monetized.

The future of regulation in this area will require a more integrated approach. It may involve either a legislative overhaul that creates a unified framework for all health-related information in the employment context or a judicial expansion of existing definitions to encompass new forms of data collection and analysis. Without such an evolution, the foundational privacy and nondiscrimination principles of the ADA, GINA, and HIPAA risk becoming obsolete, artifacts of a bygone technological era.

References

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. “Final Rule on Employer Wellness Programs and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act.” Federal Register, vol. 81, no. 95, 17 May 2016, pp. 31143-31156.

- Schilling, Brian. “What do HIPAA, ADA, and GINA Say About Wellness Programs and Incentives?” Rutgers Institute for Health, Health Care Policy and Aging Research, 2013.

- Lawley Insurance. “EEOC Issues Final Rules Under ADA and GINA on Wellness Programs.” 21 Nov. 2019.

- Koresko, T. K. and D. S. Fleder. “EEOC Releases Much-Anticipated Proposed ADA and GINA Wellness Rules.” The Wagner Law Group, 29 Jan. 2021.

- Guttman, Barbara. “GINA, the Americans with Disabilities Act, and Wellness Programs.” The American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 99, no. 5, 2016, pp. 1013-1015.

- Hyman, Mark A. “The Blood Sugar Solution ∞ The UltraHealthy Program for Losing Weight, Preventing Disease, and Feeling Great Now!” Little, Brown and Company, 2012.

- Attia, Peter. “Outlive ∞ The Science and Art of Longevity.” Harmony Books, 2023.

- Mukherjee, Siddhartha. “The Gene ∞ An Intimate History.” Scribner, 2016.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. “Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule.” Office for Civil Rights, 2013.

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. “Questions and Answers ∞ The Americans with Disabilities Act and an Employer’s Ability to Require Medical Examinations as Part of a Wellness Program.” 2016.

Reflection

The architecture of these laws provides a framework for your rights, a blueprint for the protection of your personal health narrative. You have seen how the ADA stands for equal access, how HIPAA guards your data’s privacy, and how GINA protects your very genetic potential.

This knowledge is more than an academic exercise; it is a tool for self-advocacy. When you encounter a wellness program, you are now equipped to ask incisive questions. You can look beyond the promised premium discount and see the underlying data transaction.

This understanding is the starting point of a deeper inquiry into your own health. The conversation about wellness programs is a prompt to consider the boundaries of your own privacy and the value you place on your health information. What data are you comfortable sharing, and under what conditions?

How do you define well-being for yourself, separate from any corporate metric or benchmark? The ultimate goal is to reclaim the narrative of your own biology, to be an active, informed participant in your health journey. The legal framework is the guardrail, but you are the one driving the path forward, making conscious decisions that align with your personal vision of a healthy, vital life.

Glossary

wellness program

genetic information nondiscrimination act

americans with disabilities act

health risk assessment

health insurance

employee health

voluntary participation

protected health information

health information

wellness programs

health plan

family medical history

genetic information

financial incentives

equal employment opportunity commission

ada and gina

incentive limit

aarp v. eeoc

incentive limits

de minimis incentive

economic coercion

bona fide benefit plan