Fundamentals

You have likely encountered a communication from your employer detailing a new wellness initiative. These programs arrive with promises of improved health, vitality, and sometimes, financial incentives. They invite you to track your steps, measure your blood pressure, or complete a health risk assessment.

Your personal health journey, however, is a deeply individual process, governed by a complex and elegant internal communication system. This system, your endocrine network, dictates your metabolic rate, your response to stress, your energy levels, and your body’s unique physiological signature.

The way your body functions at a cellular level determines your capacity to engage with and benefit from any standardized health protocol. It is this profound biological individuality that stands at the center of a critical legal and human question. The Americans with Disabilities Act, or ADA, provides a protective framework in this context, establishing that workplace wellness Meaning ∞ Workplace Wellness refers to the structured initiatives and environmental supports implemented within a professional setting to optimize the physical, mental, and social health of employees. initiatives must honor and accommodate the unique physiological realities of every employee.

The core principle of the ADA in this arena is the concept of voluntary participation. For a wellness program Meaning ∞ A Wellness Program represents a structured, proactive intervention designed to support individuals in achieving and maintaining optimal physiological and psychological health states. that includes medical questions or examinations ∞ such as a biometric screening Meaning ∞ Biometric screening is a standardized health assessment that quantifies specific physiological measurements and physical attributes to evaluate an individual’s current health status and identify potential risks for chronic diseases. that measures cholesterol or blood glucose ∞ your involvement must be a matter of genuine choice.

This legal standard acknowledges a fundamental biological truth ∞ a person’s health metrics are the output of an intricate system, one that may be operating under the influence of a chronic condition or a disability. A “disability” under the ADA’s protective scope includes a vast range of physiological conditions, many of which are rooted in endocrine and metabolic function.

Conditions like thyroid disorders, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), or diabetes mellitus are manifestations of a dysregulated internal environment. Therefore, a wellness program’s design must be sophisticated enough to account for these realities. It must be a tool for promoting health, a resource offered without coercion, recognizing that each person’s path to wellness is distinct.

What Is a “reasonably Designed” Program?

The ADA requires that a wellness program be “reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease.” This standard provides that the program is more than a simple data collection exercise. A program that harvests your personal health information Meaning ∞ Health Information refers to any data, factual or subjective, pertaining to an individual’s medical status, treatments received, and outcomes observed over time, forming a comprehensive record of their physiological and clinical state. without providing tailored feedback, educational resources, or confidential support from health professionals fails this test.

The design must have a legitimate chance of improving health for those who participate. For instance, a program that uses aggregate, anonymized data to offer targeted workshops on stress reduction or nutrition addresses a collective need. A program that screens for high blood pressure Meaning ∞ Blood pressure quantifies the force blood exerts against arterial walls. and then provides resources for managing it is a supportive intervention.

The structure of the program itself must be health-promoting. It cannot be unduly burdensome, requiring excessive time commitments, or involve invasive procedures that carry their own risks. This principle ensures that the “wellness” label is substantiated by the program’s actual function and intent, aligning the employer’s initiative with the genuine health interests of the employee.

A program’s design must substantively promote health, extending beyond mere data collection to offer genuine support and resources.

This concept of a reasonable design also acts as a safeguard. It prevents a wellness program from becoming a subterfuge, a disguised method for uncovering health information to be used for discriminatory purposes. The ADA’s framework is built on a foundation of trust and confidentiality.

Your personal medical data, whether it pertains to your hormonal status, your metabolic markers, or a diagnosed condition, is protected. An employer cannot require you to waive these confidentiality protections as a condition of participation. The information you share within the confines of a voluntary wellness program is to be used for one purpose ∞ to support your health journey.

This legal boundary is absolute, creating a secure space for you to engage with health resources while preserving your privacy and protecting you from potential bias in the workplace.

How Does the ADA Define a Disability?

To appreciate the full scope of the ADA’s application, one must understand its definition of disability. The Act protects individuals who have a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities. This definition is broad and inclusive.

Major life activities encompass a wide range of functions, including the operation of major bodily systems. The endocrine system Meaning ∞ The endocrine system is a network of specialized glands that produce and secrete hormones directly into the bloodstream. is explicitly listed as a major bodily system. This has profound implications for wellness programs. An individual with hypothyroidism, for example, has a condition affecting the endocrine system that can substantially limit metabolic function, energy levels, and even cognitive processes.

Similarly, an individual with Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes has a disability affecting the endocrine and digestive systems. These are not temporary states of ill health; they are chronic physiological conditions that require careful management and medical oversight.

The ADA’s protection extends to individuals with a record of such an impairment or those who are “regarded as” having an impairment. This comprehensive definition ensures that the protections are not limited to only the most visible or obvious conditions. Many metabolic and hormonal disorders are invisible.

You cannot see that a person’s pancreas is producing insufficient insulin or that their thyroid gland is underactive. Yet, these internal states have a powerful impact on the individual’s life and their ability to meet standardized health metrics.

A wellness program that penalizes an employee for having a high body mass index (BMI) or elevated blood sugar levels may be inadvertently discriminating against someone whose metabolic state is a direct consequence of a protected disability. The ADA compels a more nuanced and accommodating approach, one that looks beyond the raw data point to the person and their unique biological context.

Intermediate

The architecture of employer wellness Meaning ∞ Employer wellness represents a structured organizational initiative designed to support and enhance the physiological and psychological well-being of a workforce, aiming to mitigate health risks and optimize individual and collective health status. programs, when viewed through the lens of the Americans with Disabilities Act, reveals a complex interplay between legal standards and human physiology. The central pillar of this interaction is the requirement of “voluntariness,” a concept that the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Meaning ∞ The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, EEOC, functions as a key regulatory organ within the societal framework, enforcing civil rights laws against workplace discrimination. (EEOC) has sought to clarify through evolving guidance.

A program’s voluntary nature is assessed by examining the degree of pressure, financial or otherwise, placed upon an employee to participate. This is particularly relevant for programs that go beyond simple participation and are instead “health-contingent,” meaning they require an individual to achieve a specific health outcome to earn an incentive.

It is at this juncture that a person’s unique endocrine and metabolic function becomes a critical variable. A health goal that is readily achievable for one person may be a clinical impossibility for another, due to an underlying physiological condition that constitutes a disability under the ADA.

The regulatory framework distinguishes between two primary categories of wellness programs. Understanding this distinction is essential to analyzing how the ADA applies. The first type is the “participatory” program, where the incentive is provided simply for taking part in an activity. The second is the “health-contingent” program, which demands more.

These are further divided into activity-only and outcome-based programs. An activity-only program might require an employee to walk a certain number of steps per day. An outcome-based program ties the incentive to a specific physiological result, such as reaching a target cholesterol level.

The ADA’s scrutiny intensifies as a program moves from simple participation to requiring the achievement of specific health metrics, because the latter has a greater potential to penalize individuals based on factors related to a disability.

Participatory versus Health Contingent Programs

The two main structures of wellness programs Meaning ∞ Wellness programs are structured, proactive interventions designed to optimize an individual’s physiological function and mitigate the risk of chronic conditions by addressing modifiable lifestyle determinants of health. have different implications under the law. A participatory program is generally viewed as less coercive because the reward is disconnected from any specific health outcome. The focus is on engagement rather than achievement.

- Participatory Programs ∞ These programs reward an employee for completing an action, irrespective of the results. Examples include completing a Health Risk Assessment (HRA), attending a nutritional seminar, or undergoing a biometric screening. The incentive is given for the act of participation itself. From an ADA perspective, these are often less problematic, provided the incentive is not so large as to be considered coercive, effectively making participation non-voluntary.

- Health-Contingent Programs ∞ These programs require an individual to satisfy a standard related to a health factor to obtain a reward. An activity-only program is a subset where an individual must perform a specific activity (e.g. adhere to a walking program) but does not need to achieve a specific outcome. An outcome-based program requires an individual to attain a particular result (e.g. maintain a blood pressure below 120/80 mmHg). It is these outcome-based programs that receive the most rigorous examination under the ADA.

The reason for this heightened scrutiny is clear. An individual with a diagnosed thyroid condition (hypothyroidism) may have a slower metabolism that makes weight loss exceedingly difficult, even with diligent effort. An individual with familial hypercholesterolemia, a genetic disorder, may be unable to lower their LDL cholesterol to a specified target through diet and exercise alone.

In these cases, a program that penalizes the employee for not reaching the target is penalizing them for the manifestation of a disability. This is where the ADA’s requirement for a reasonable accommodation Meaning ∞ Reasonable accommodation refers to the necessary modifications or adjustments implemented to enable an individual with a health condition to achieve optimal physiological function and participate effectively in their environment. becomes paramount.

The Critical Role of Reasonable Accommodation

What is a reasonable accommodation in a wellness program? A reasonable accommodation is a modification or adjustment that enables an employee with a disability to participate in the program and have an equal opportunity to earn the associated rewards. The ADA mandates that employers provide such accommodations, unless doing so would cause an “undue hardship” for the employer.

This is a proactive and interactive process. The employer and employee are expected to engage in a dialogue to identify an effective accommodation. For outcome-based wellness programs, this often means providing an alternative standard or a waiver of the standard altogether.

Reasonable accommodation ensures that an individual’s opportunity to earn a wellness incentive is based on effort, not on a physiological state beyond their control.

Consider an employee with Type 2 diabetes, a condition recognized as a disability. The company’s wellness program offers a significant insurance premium discount to employees who maintain a fasting blood glucose level below 100 mg/dL. For this particular employee, despite strict adherence to their medical treatment plan, their blood sugar levels may consistently run higher.

A reasonable accommodation would be to provide an alternative path to earning the discount. This could involve demonstrating that they are following their doctor’s recommendations, attending regular check-ups, or completing a diabetes education course. The accommodation shifts the focus from achieving a specific biometric marker, which may be unattainable due to their disability, to actively managing their health, which is the ultimate goal of any well-designed program.

The table below illustrates potential reasonable accommodations for common health-contingent standards, linking them to underlying endocrine or metabolic conditions.

| Wellness Program Standard | Associated Medical Condition (Disability) | Example of a Reasonable Accommodation |

|---|---|---|

| Achieve a Body Mass Index (BMI) below 25 | Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), Hypothyroidism | Provide a physician’s note confirming the condition and adherence to a treatment plan. Offer an alternative standard, such as completing a certain number of workouts per month. |

| Lower LDL Cholesterol to below 100 mg/dL | Familial Hypercholesterolemia | Waive the biometric requirement and grant the reward based on evidence of compliance with a prescribed medication regimen (e.g. statins). |

| Maintain Blood Pressure below 120/80 mmHg | Chronic Kidney Disease, Adrenal Disorders | Allow the employee to work with their own physician to set an alternative, medically appropriate blood pressure target and provide documentation of their efforts to reach it. |

Incentives and the Question of Coercion

The value of the incentive offered is a key determinant of whether a program is truly voluntary. If the financial reward for participation is so large, or the penalty for non-participation so severe, that an employee feels they have no real choice but to disclose their personal health information, the program may be deemed coercive and thus in violation of the ADA.

The EEOC’s position on this has shifted over time. For years, guidance aligned with the Affordable Care Act, permitting incentives up to 30% of the total cost of self-only health insurance coverage. However, legal challenges and subsequent court rulings have questioned this standard, arguing that such a high amount could be coercive for many employees.

More recent proposed rules have suggested a much lower threshold, allowing only “de minimis” incentives (such as a water bottle or a gift card of modest value) for programs that require medical examinations or disability-related inquiries.

This stricter stance reflects a deep concern for protecting employees from feeling economically compelled to participate in a program that requires them to reveal sensitive information about their health and potential disabilities. While the specific legal limits remain a subject of regulatory debate, the underlying principle is consistent ∞ the choice to participate must be freely made.

An employer must design its wellness program in a way that respects this principle, ensuring that the incentive serves as a gentle encouragement, an invitation to engage with health resources, rather than a powerful financial lever that overrides an individual’s right to privacy and autonomy over their own medical information.

Academic

The intersection of the Americans with Disabilities Act Meaning ∞ The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), enacted in 1990, is a comprehensive civil rights law prohibiting discrimination against individuals with disabilities across public life. and employer wellness programs represents a sophisticated legal and bioethical challenge. A systems-biology perspective provides a powerful analytical framework for understanding the potential for discrimination inherent in one-size-fits-all wellness initiatives.

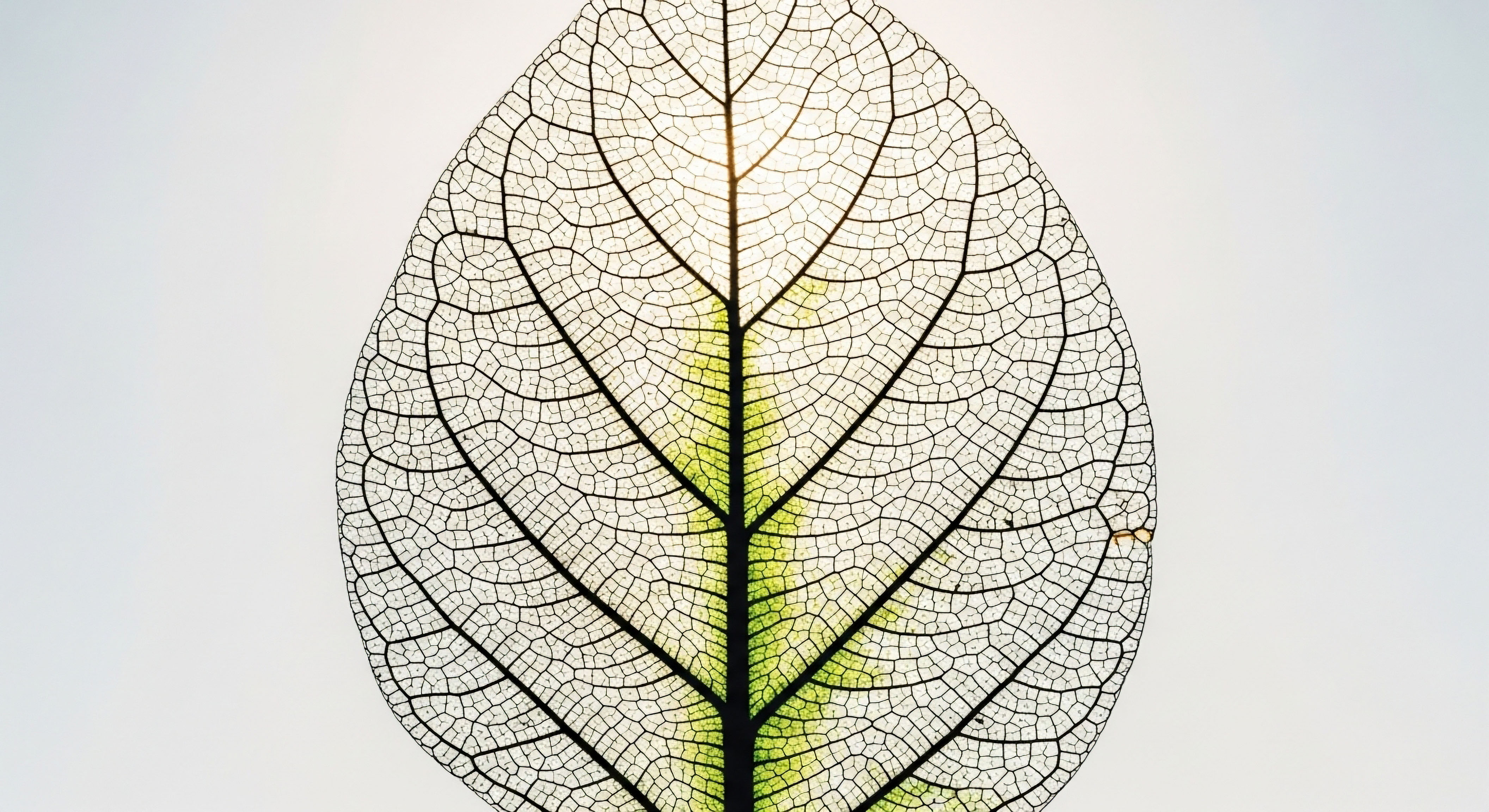

Human beings are not standardized machines; each individual possesses a unique and dynamic biological milieu, orchestrated largely by the complex interplay of the neuroendocrine and metabolic systems. The concept of allostasis, and its pathological counterpart, allostatic load, offers a scientifically robust model for conceptualizing how poorly designed wellness programs can disproportionately burden individuals with disabilities, thereby violating the spirit and letter of the ADA.

Allostasis refers to the process of maintaining physiological stability, or homeostasis, through adaptation. The body constantly adjusts its internal parameters ∞ hormone levels, glucose, blood pressure ∞ in response to external and internal stressors. This adaptation is primarily mediated by the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis and the autonomic nervous system.

When these systems are chronically activated, due to persistent stress or an underlying physiological disorder, the result is allostatic load Meaning ∞ Allostatic load represents the cumulative physiological burden incurred by the body and brain due to chronic or repeated exposure to stress. ∞ the cumulative “wear and tear” on the body. Elevated allostatic load is a precursor to and an exacerbator of numerous chronic diseases, including the very conditions wellness programs purport to prevent, such as cardiovascular disease and Type 2 diabetes.

An individual with a pre-existing endocrine or metabolic disability often operates with a higher baseline allostatic load, meaning their capacity for further adaptation is diminished.

Allostatic Load and Health Contingent Programs

How does a wellness program increase allostatic load? Consider a health-contingent wellness program that imposes a significant financial penalty on employees who fail to meet a specific biometric target, such as a waist circumference measurement or a fasting insulin level.

For an employee with a condition like Cushing’s syndrome (characterized by excess cortisol) or PCOS (characterized by insulin resistance and androgen excess), these metrics are direct manifestations of their underlying pathophysiology. The demand to normalize these markers through willpower alone is a physiological impossibility.

The persistent pressure to achieve the unattainable, coupled with the financial threat of the penalty, acts as a potent chronic stressor. This stress activates the HPA axis, leading to further cortisol release, which in turn can worsen insulin resistance and central adiposity. The wellness program, in this context, becomes iatrogenic. It creates a vicious cycle, increasing the allostatic load of the very individual it is supposed to be helping, and penalizing them for the biological consequences.

This systems-level view reveals the inadequacy of a superficial application of the ADA. The requirement for a “reasonable accommodation” must be interpreted through this biological lens. Providing an alternative standard is the minimum legal requirement. A more profound understanding would compel employers to design programs that are inherently flexible and account for biological variability from the outset.

This approach moves beyond a reactive accommodation model to a proactive, universally designed one. Such a program would prioritize personalized risk assessment Meaning ∞ Risk Assessment refers to the systematic process of identifying, evaluating, and prioritizing potential health hazards or adverse outcomes for an individual patient. and education over punitive, outcome-based metrics. It would leverage an individual’s own health data to provide confidential, actionable insights, rather than comparing them against a rigid, population-based standard that fails to respect their unique endocrine and metabolic state.

Genetic Information and the GINA Interface

The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act Meaning ∞ The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) is a federal law preventing discrimination based on genetic information in health insurance and employment. (GINA) adds another layer of complexity, working in concert with the ADA to protect employees. GINA prohibits discrimination based on genetic information, which includes not only the results of genetic tests but also an individual’s family medical history.

Many wellness programs ask employees to complete a Health Risk Assessment Meaning ∞ A Health Risk Assessment is a systematic process employed to identify an individual’s current health status, lifestyle behaviors, and predispositions, subsequently estimating the probability of developing specific chronic diseases or adverse health conditions over a defined period. (HRA) that includes questions about their family’s health history (e.g. “Has a parent ever had heart disease or diabetes?”). Under GINA, an employer generally cannot offer an incentive for the provision of genetic information. This creates a critical distinction. An employer can offer an incentive for completing an HRA, but not for answering the specific questions related to family medical history.

The legal framework mandates a separation between incentivizing wellness engagement and coercing the disclosure of an individual’s genetic blueprint.

The table below delineates the permissible and impermissible uses of incentives under the combined ADA and GINA framework, highlighting the nuanced legal boundaries.

| Program Component | ADA Implication | GINA Implication | Permissibility of Incentive |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biometric Screening (Blood Pressure, Cholesterol) | Permitted if voluntary. Incentive size is regulated to prevent coercion. A medical examination. | No direct implication, unless genetic tests are performed on the sample. | Yes, subject to the ADA’s limits on coercion (e.g. “de minimis” or a percentage cap, depending on current regulations). |

| Health Risk Assessment (Questions about diet, exercise) | Permitted if voluntary. These are disability-related inquiries. | No implication. | Yes, subject to the ADA’s limits. |

| Health Risk Assessment (Questions about family medical history) | A disability-related inquiry. | This is a request for “genetic information.” | No. An employer cannot offer a reward or impose a penalty for answering these specific questions. |

| Spouse Participation (Biometric Screening) | Considered a disability-related inquiry about the employee. | The spouse’s health information is considered genetic information about the employee. | No. An employer cannot offer more than a de minimis incentive for a spouse to provide information to a wellness program. |

This intricate legal matrix underscores a fundamental principle ∞ the law seeks to create a firewall between an individual’s most sensitive biological data ∞ their current health status and their genetic predispositions ∞ and the economic pressures of the workplace. From a systems-biology perspective, this is entirely logical.

An individual’s genome and their current physiological state are deeply intertwined. A genetic predisposition, such as carrying the APOE4 allele, which increases the risk for Alzheimer’s disease and cardiovascular issues, is a piece of information that GINA protects. A wellness program that probes this area, even indirectly through family history, treads on sensitive ground.

The legal framework recognizes that true wellness promotion cannot be built upon a foundation of coerced disclosure. It must be built on trust, confidentiality, and a profound respect for the biological autonomy of the individual.

What Is the Future of Wellness Program Regulation?

The legal and regulatory landscape for wellness programs is in a state of flux. Court decisions have invalidated previous EEOC rules, and new regulations are subject to political and administrative review. The core tension remains unresolved ∞ how to balance an employer’s interest in promoting a healthier workforce with an employee’s right to be free from discrimination and to maintain the privacy of their health information.

The trend appears to be moving towards a more protective stance for employees, particularly concerning the size of incentives. The shift in proposed rules from a 30% incentive cap to a “de minimis” standard for many programs indicates a growing recognition of the coercive potential of large financial inducements.

A future, more enlightened model of workplace wellness might abandon outcome-based contingencies altogether. Instead, it would focus on providing all employees with access to high-quality, confidential resources. This could include subsidized access to registered dietitians, health coaches, mental health professionals, and advanced preventative screenings offered on a truly voluntary basis.

Such a model aligns with the principles of the ADA by being inherently inclusive and non-discriminatory. It promotes health by empowering individuals with tools and knowledge, trusting them to make the best decisions for their own bodies, in consultation with their healthcare providers.

This approach respects the complex reality of human physiology and acknowledges that health is a personal journey, one that cannot be mandated or measured by a universal yardstick. It is a journey that the law, in its wisdom, seeks to protect.

References

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (2016). Regulations Under the Americans with Disabilities Act. Federal Register, 81(103), 31125-31156.

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (2016). Regulations Under the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008. Federal Register, 81(103), 31143-31156.

- Mello, M. M. & Rosenthal, M. B. (2016). Wellness programs and the Affordable Care Act. The New England Journal of Medicine, 374(24), 2301 ∞ 2303.

- Schmidt, H. Asch, D. A. & Ubel, P. A. (2016). The limits of wellness programs. The New England Journal of Medicine, 374(24), 2303 ∞ 2305.

- Madison, K. M. (2016). The law, policy, and ethics of employers’ use of financial incentives to improve health. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 44(1), 60-68.

- McEwen, B. S. (1998). Stress, adaptation, and disease ∞ Allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 840(1), 33-44.

- Juster, R. P. McEwen, B. S. & Lupien, S. J. (2010). Allostatic load and allostasis ∞ a theoretical overview of its underlying mechanisms and measurement. Stress, 13(6), 441-457.

- Feldman, R. D. (2017). Aldosterone and blood pressure ∞ a story in evolution. Journal of the American Society of Hypertension, 11(12), 833-835.

- Legro, R. S. Arslanian, S. A. Ehrmann, D. A. Hoeger, K. M. Murad, M. H. Pasquali, R. & Welt, C. K. (2013). Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome ∞ an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 98(12), 4565-4592.

- Jonker, J. T. & De Laet, C. (2019). The Americans with Disabilities Act and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act ∞ An overview of the regulations of workplace wellness programs. Benefits Quarterly, 35(1), 26-36.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a map of the complex territory where law and human biology meet. This map details the rules, the physiological principles, and the protective boundaries established to ensure fairness and respect for individual health realities. Your own body is a unique landscape, with its own history, its own patterns of communication, and its own specific needs.

The knowledge of how legal frameworks like the ADA seek to honor this individuality is a powerful first step. It transforms the conversation from one of compliance to one of deep, personal understanding.

Consider your own experiences with health and wellness initiatives. How do they align with your body’s specific requirements? What does it mean to you to participate in a program that is truly voluntary, one that provides support without pressure and honors your privacy without condition?

The ultimate goal of this exploration is to equip you with a new lens through which to view these programs. It is a lens that recognizes the profound connection between your internal world ∞ the intricate dance of your hormones and metabolism ∞ and the external structures you navigate every day.

Your health journey is yours alone to direct. The knowledge you have gained is not an endpoint, but a tool for advocacy, for introspection, and for charting a course that is authentically and powerfully your own.