Fundamentals

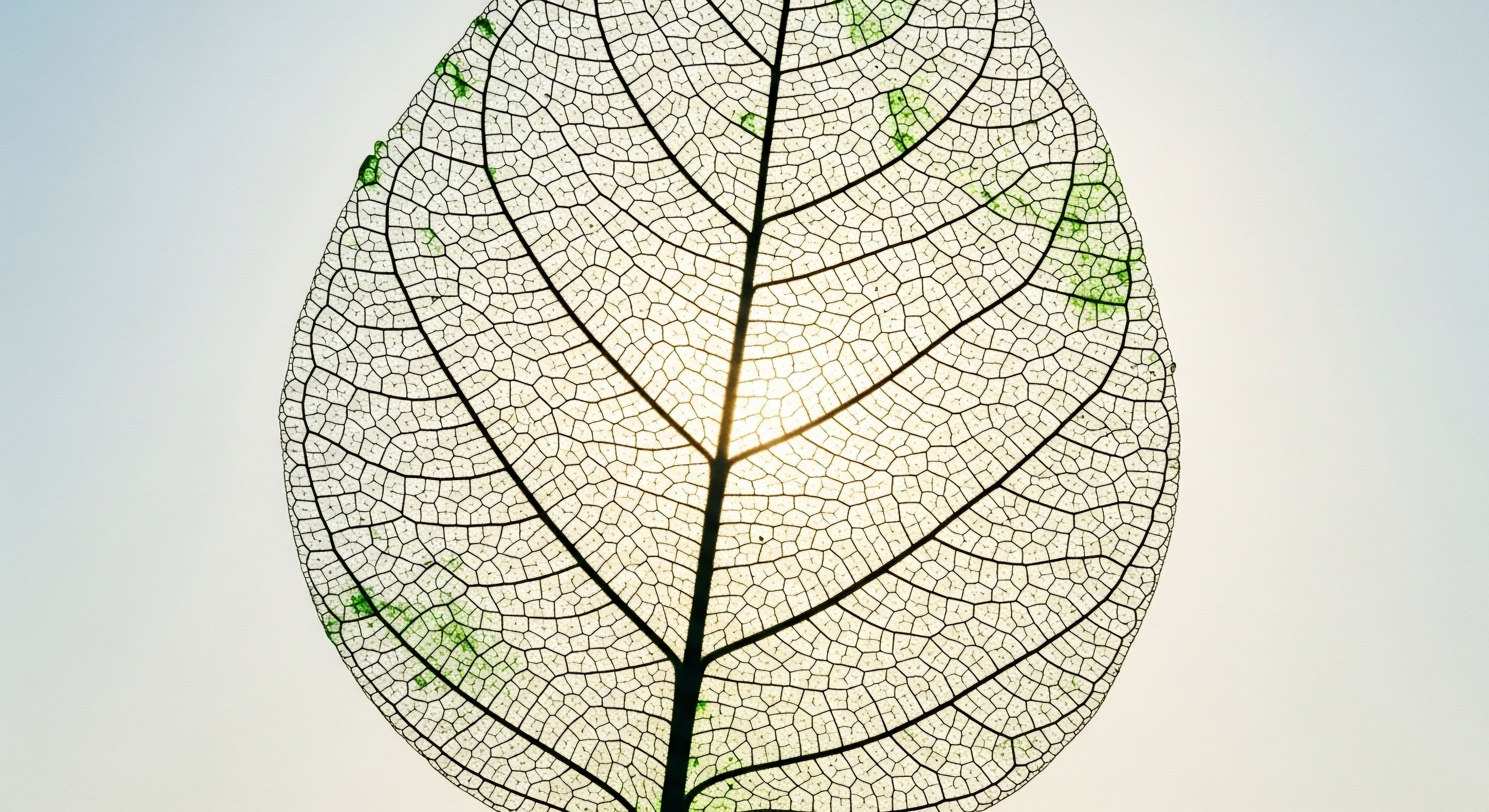

The conversation around workplace wellness Meaning ∞ Workplace Wellness refers to the structured initiatives and environmental supports implemented within a professional setting to optimize the physical, mental, and social health of employees. often begins with programs and incentives. A deeper understanding of your own biological systems, however, reveals a more profound starting point ∞ the principle of voluntary participation. Your body possesses an intricate intelligence, a finely tuned system that seeks equilibrium.

When an external program, even one with good intentions, imposes itself in a way that feels coercive, it can register as a threat. This perception, conscious or subconscious, initiates a cascade of physiological responses. The question of how the Americans with Disabilities Act’s (ADA) voluntary requirement affects wellness program Meaning ∞ A Wellness Program represents a structured, proactive intervention designed to support individuals in achieving and maintaining optimal physiological and psychological health states. design is a legal and ethical one.

From a biological perspective, it is a fundamental acknowledgment of your body’s need for autonomy to maintain its delicate hormonal and metabolic balance. A program that respects your voluntary choice is a program that works with your biology, not against it.

The ADA’s stipulation that employee participation in wellness programs Meaning ∞ Wellness programs are structured, proactive interventions designed to optimize an individual’s physiological function and mitigate the risk of chronic conditions by addressing modifiable lifestyle determinants of health. that include medical inquiries or exams must be voluntary is a safeguard for your well-being. This legal protection aligns with a core principle of human physiology ∞ the body thrives in an environment of safety and predictability.

When a wellness program feels mandatory, perhaps due to substantial financial penalties for non-participation, it can trigger a persistent state of low-grade stress. This chronic activation of your stress response Meaning ∞ The stress response is the body’s physiological and psychological reaction to perceived threats or demands, known as stressors. system, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, can have far-reaching consequences for your health.

It can disrupt the rhythmic release of cortisol, a primary stress hormone, which in turn can affect your sleep, your mood, your immune function, and your metabolism. A truly voluntary program, therefore, is one that supports your health journey without compromising your internal sense of control.

A wellness program that honors your voluntary participation is a program that respects your body’s innate need for autonomy and balance.

The Body’s Response to Coercion

To appreciate the significance of the ADA’s voluntary requirement, it is helpful to understand how your body perceives and responds to pressure. Your nervous system is constantly scanning your environment for cues of safety and danger. A wellness program that feels coercive, even if it is presented as a benefit, can be interpreted by your nervous system as a threat.

This can activate the sympathetic nervous system, the body’s “fight or flight” response. This response is designed for short-term survival, but when it is chronically activated by a stressful work environment, it can lead to a state of physiological dysregulation. This can manifest as increased heart rate, elevated blood pressure, and digestive issues. Over time, this chronic stress Meaning ∞ Chronic stress describes a state of prolonged physiological and psychological arousal when an individual experiences persistent demands or threats without adequate recovery. can contribute to the development of more serious health conditions.

The ADA’s voluntary requirement, in essence, creates a space for you to engage with your health on your own terms. It allows you to choose wellness activities that are meaningful and appropriate for you, without the added pressure of financial coercion. This sense of agency is a powerful contributor to your overall well-being.

When you feel in control of your health choices, you are more likely to be intrinsically motivated to make positive changes. This intrinsic motivation Meaning ∞ Intrinsic motivation signifies engaging in an activity for its inherent satisfaction, not for external rewards. is far more sustainable than the extrinsic motivation of a financial reward or penalty. A well-designed wellness program, therefore, will focus on empowering you with knowledge and resources, rather than on compelling you to participate through incentives.

The Hormonal Impact of Stress

The chronic stress that can result from a coercive wellness program A coercive wellness incentive is a chronic stressor that dysregulates your hormones, undermining health under the guise of promoting it. can have a profound impact on your hormonal health. The HPA axis, your body’s central stress response system, is designed to release cortisol in response to a perceived threat.

In a healthy individual, cortisol levels Meaning ∞ Cortisol levels refer to the quantifiable concentration of cortisol, a primary glucocorticoid hormone, circulating within the bloodstream. follow a natural daily rhythm, peaking in the morning to help you wake up and gradually declining throughout the day. Chronic stress can disrupt this rhythm, leading to elevated cortisol levels at night, which can interfere with sleep, or flattened cortisol levels throughout the day, which can leave you feeling fatigued and depleted. This dysregulation of cortisol can have a domino effect on other hormones, including thyroid hormones, sex hormones, and insulin.

For example, high levels of cortisol can suppress the production of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), which can lead to hypothyroidism, a condition characterized by fatigue, weight gain, and depression. Elevated cortisol can also interfere with the production of sex hormones like testosterone and estrogen, which can impact libido, fertility, and mood.

Furthermore, chronic stress and high cortisol levels are strongly linked to insulin resistance, a condition in which your cells become less responsive to the effects of insulin. Insulin resistance Meaning ∞ Insulin resistance describes a physiological state where target cells, primarily in muscle, fat, and liver, respond poorly to insulin. is a major risk factor for type 2 diabetes and other metabolic disorders. The ADA’s voluntary requirement, by mitigating the potential for chronic stress in the workplace, can be seen as a protective measure for your long-term hormonal and metabolic health.

Designing for Wellness Autonomy

A wellness program that truly supports your health will be designed with your autonomy in mind. This means moving beyond a one-size-fits-all approach and offering a range of options that cater to different needs, preferences, and abilities.

A program that is “reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease,” as stipulated by the EEOC, should provide you with meaningful information and support. This might include educational resources on nutrition and stress management, access to health coaching, or opportunities for physical activity that are enjoyable and accessible. The focus should be on empowerment, not compliance.

The design of such a program should also prioritize confidentiality. The ADA requires that any medical information collected as part of a wellness program be kept confidential and separate from your personnel records. This is a critical component of building trust and ensuring that you feel safe participating in the program.

When you know that your personal health information is protected, you are more likely to engage openly and honestly with the resources offered. A program that respects your privacy is a program that respects you as an individual. This respect is the foundation of a healthy and supportive workplace culture.

- Personalized Pathways ∞ A program that offers a variety of wellness activities, from mindfulness apps to nutrition counseling, allows you to choose what is most relevant to your personal health goals.

- Educational Empowerment ∞ Providing access to reliable health information empowers you to make informed decisions about your well-being.

- Confidential Coaching ∞ Offering confidential access to health coaches can provide personalized support and guidance without the fear of judgment or reprisal.

Intermediate

The regulatory landscape governing workplace wellness programs is complex, shaped by the interplay of several federal laws, including the Americans with Disabilities Act Meaning ∞ The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), enacted in 1990, is a comprehensive civil rights law prohibiting discrimination against individuals with disabilities across public life. (ADA), the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act Meaning ∞ The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) is a federal law preventing discrimination based on genetic information in health insurance and employment. (GINA).

The ADA’s voluntary requirement The ADA’s ‘voluntary’ rule shapes wellness programs that gather surface data, creating a critical gap between legal compliance and true biological understanding. is a central pillar of this framework, directly influencing the design of wellness programs and the structure of incentives. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Menopause is a data point, not a verdict. (EEOC) has provided guidance on how to interpret this requirement, establishing a standard that wellness programs must be “reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease.” This standard moves beyond a superficial checklist of activities and requires a more thoughtful and evidence-based approach to program design.

A program that is reasonably designed Meaning ∞ Reasonably designed refers to a therapeutic approach or biological system structured to achieve a specific physiological outcome with minimal disruption. is one that provides participants with personalized feedback and resources, rather than simply collecting data for the sake of data collection.

The issue of incentives is particularly contentious. The EEOC has historically set a limit on incentives for participation in wellness programs that include medical inquiries or exams at 30% of the cost of self-only health coverage. This limit was intended to strike a balance between encouraging participation and ensuring that the program remains truly voluntary.

A financial incentive that is too large could be seen as coercive, effectively forcing employees to disclose their personal health information. The legal status of this incentive limit has been subject to change, creating a degree of uncertainty for employers.

From a clinical perspective, the debate over incentive size highlights a more fundamental question about what truly motivates behavior change. While incentives can be effective in the short term, sustainable health improvements are more likely to be driven by intrinsic motivation and a genuine desire to improve one’s well-being.

A “reasonably designed” wellness program provides personalized feedback and resources, fostering genuine engagement rather than mere data collection.

Participatory versus Health Contingent Programs

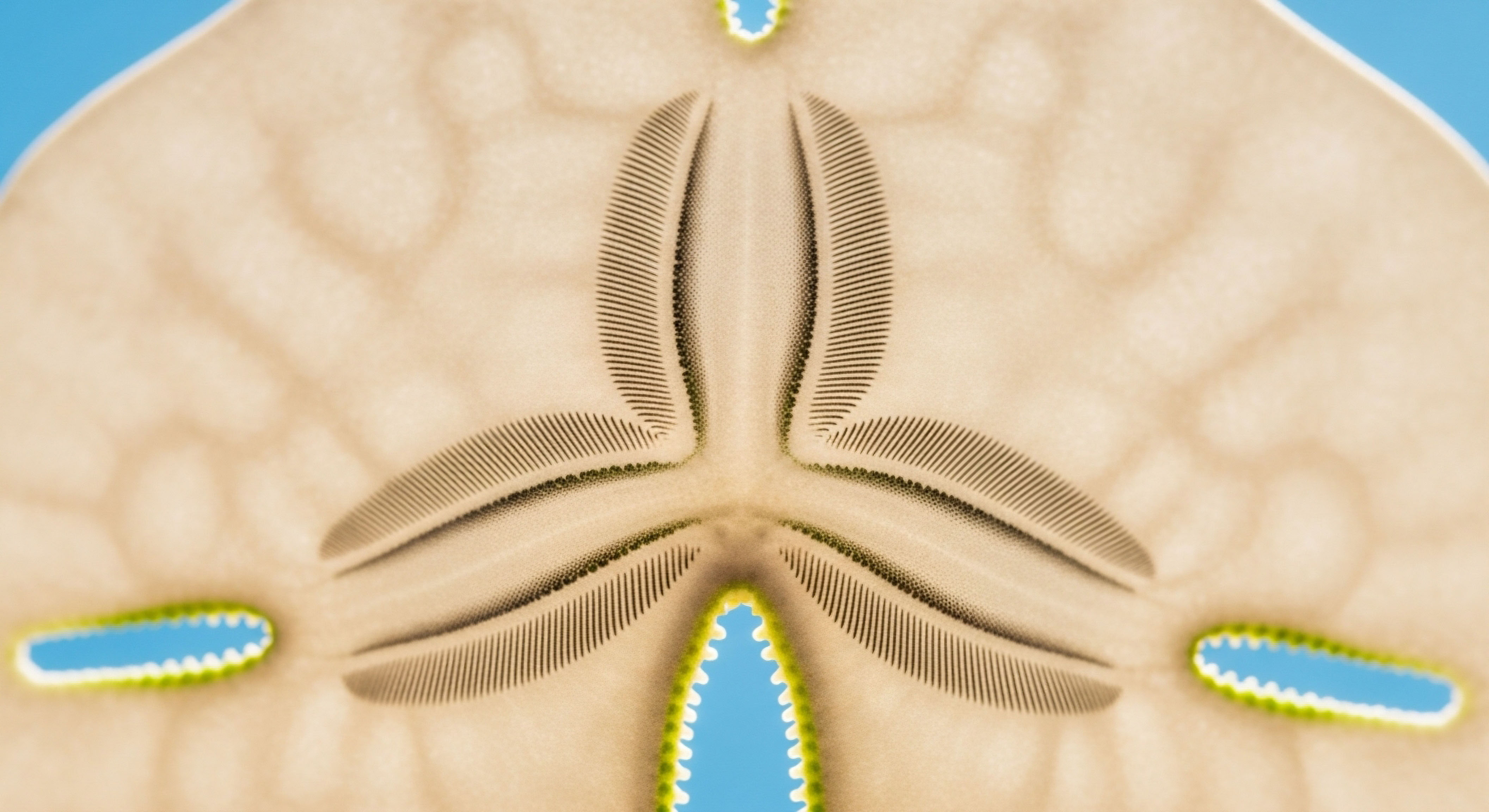

Wellness programs can be broadly categorized into two types ∞ participatory and health-contingent. The ADA’s voluntary requirement applies to both types of programs if they include disability-related inquiries or medical examinations. Understanding the distinction between these two types of programs is essential for designing a compliant and effective wellness initiative.

Participatory wellness programs do not require an individual to meet a specific health-related standard to earn a reward. Examples of participatory programs include completing a health risk assessment (HRA), attending a nutrition seminar, or participating in a walking challenge. The reward is contingent on participation, not on achieving a particular outcome.

Health-contingent wellness programs, on the other hand, require individuals to meet a specific health standard to obtain a reward. These programs can be further divided into two subcategories ∞ activity-only and outcome-based.

- Activity-Only Programs ∞ These programs require an individual to perform or complete a health-related activity, but they do not require the attainment of a specific health outcome. An example would be a walking program that requires participants to walk a certain number of steps per day to earn a reward.

- Outcome-Based Programs ∞ These programs require an individual to attain or maintain a specific health outcome to receive a reward. Examples include achieving a certain body mass index (BMI) or cholesterol level.

HIPAA regulations require health-contingent programs Meaning ∞ Health-Contingent Programs are structured wellness initiatives that offer incentives or disincentives based on an individual’s engagement in specific health-related activities or the achievement of predetermined health outcomes. to offer a reasonable alternative standard A reasonable alternative standard redefines wellness from a generic metric to a personalized protocol that restores your unique biological function. for individuals for whom it is medically inadvisable or unreasonably difficult to meet the initial standard. The EEOC has indicated that complying with HIPAA’s reasonable alternative standard will generally satisfy an employer’s obligation to provide a reasonable accommodation under the ADA for a health-contingent program.

For participatory programs, the ADA may require a reasonable accommodation Meaning ∞ Reasonable accommodation refers to the necessary modifications or adjustments implemented to enable an individual with a health condition to achieve optimal physiological function and participate effectively in their environment. even though HIPAA does not mandate a reasonable alternative standard. For instance, an employer might need to provide materials in an accessible format for an employee with a visual impairment.

The Role of Incentives in Program Design

The use of incentives in wellness programs is a double-edged sword. On one hand, incentives can be a powerful tool for encouraging employees to participate in activities that they might otherwise neglect. On the other hand, if the incentive is too large, it can undermine the voluntary nature of the program and create a sense of coercion.

The EEOC’s 30% incentive limit was an attempt to find a middle ground, but the ongoing legal debate suggests that there is no easy answer to the question of how much is too much. From a clinical and behavioral science perspective, the focus on financial incentives Meaning ∞ Financial incentives represent structured remuneration or benefits designed to influence patient or clinician behavior towards specific health-related actions or outcomes, often aiming to enhance adherence to therapeutic regimens or promote preventative care within the domain of hormonal health management. may be misplaced. True wellness is not something that can be bought or sold. It is a state of being that arises from a deep commitment to one’s own health and well-being.

A more effective approach to program design might be to focus on creating a culture of wellness within the organization. This involves more than just offering a menu of wellness activities. It requires a genuine commitment from leadership to support the health and well-being Meaning ∞ Health and Well-Being signifies a state of physical, mental, and social soundness, beyond mere absence of illness. of employees.

This might include creating flexible work schedules, providing healthy food options in the workplace, and encouraging regular breaks for physical activity and mental rest. When employees feel that their employer genuinely cares about their well-being, they are more likely to be engaged and productive. In this type of environment, financial incentives become less important, and intrinsic motivation takes center stage.

| Program Element | ADA Requirement | Clinical Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Participation | Must be voluntary; incentives cannot be coercive. | Reduces stress and promotes a sense of autonomy, which is beneficial for mental and physical health. |

| Design | Must be “reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease.” | Ensures that the program is evidence-based and provides meaningful support to participants. |

| Confidentiality | Medical information must be kept confidential and separate from personnel files. | Builds trust and encourages open participation in the program. |

| Accommodations | Reasonable accommodations must be provided for employees with disabilities. | Ensures that all employees have an equal opportunity to participate and benefit from the program. |

The Limits of a One Size Fits All Approach

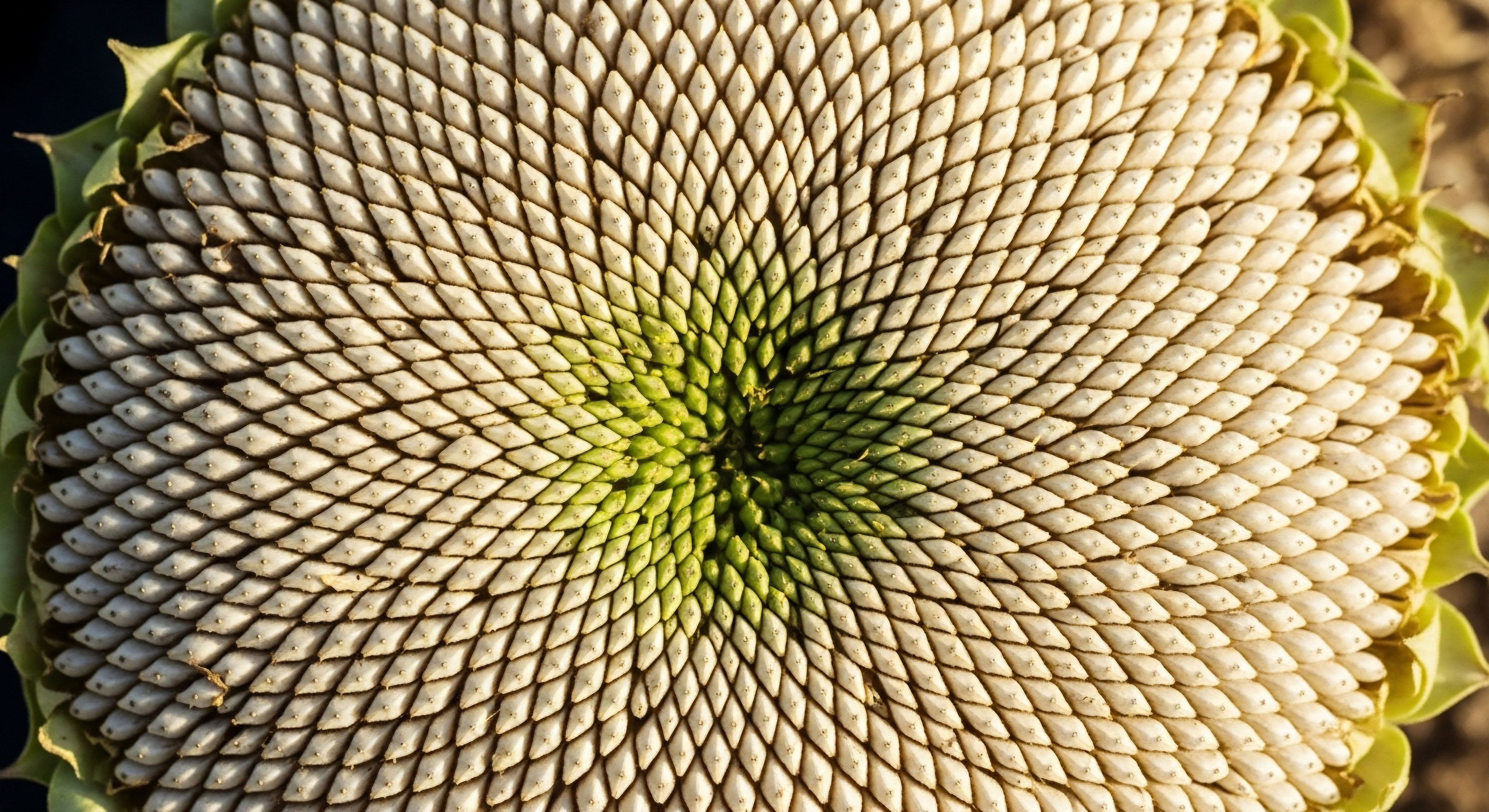

The human body is a complex and dynamic system, and there is no single definition of what it means to be healthy. A wellness program that relies on a narrow set of biometric markers, such as BMI or cholesterol levels, fails to capture the full picture of an individual’s health.

This one-size-fits-all approach can be particularly problematic for individuals with chronic health conditions or disabilities. The ADA’s requirement for reasonable accommodations is a legal recognition of this fact. From a clinical perspective, a personalized approach to wellness is always preferable. This means taking into account an individual’s unique health history, lifestyle, and goals.

A truly effective wellness program will empower individuals to become active participants in their own health care. This might involve providing them with tools and resources to track their own health data, such as wearable devices that monitor activity levels and sleep patterns.

However, it is important to ensure that the use of such devices is truly voluntary and that the data collected is used to support the individual’s health goals, not to penalize them for failing to meet certain targets. The focus should always be on progress, not perfection. A program that celebrates small victories and provides support for setbacks is more likely to be successful in the long run.

Academic

The intersection of workplace wellness programs and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) presents a fascinating case study in the tension between public health objectives and individual liberties. The ADA’s insistence on the voluntary nature of wellness programs that involve medical inquiries is a legal mandate with profound psychoneuroendocrine implications.

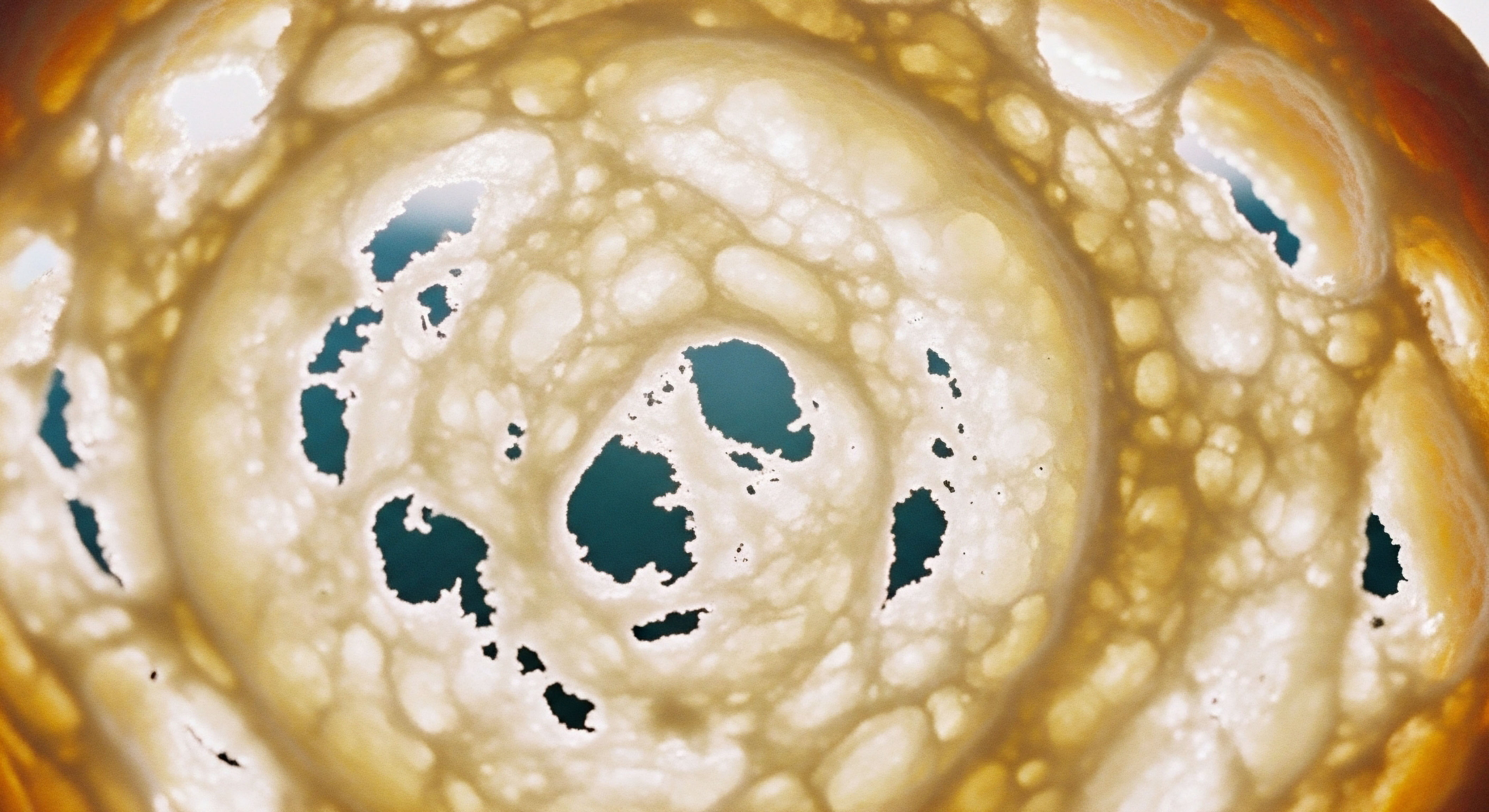

A deeper analysis of this requirement reveals its alignment with our understanding of the deleterious effects of chronic stress on human physiology. When a wellness program is perceived as coercive, it can act as a chronic psychosocial stressor, activating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic-adrenal-medullary (SAM) system.

The sustained activation of these systems can lead to a state of allostatic overload, a concept that describes the cumulative wear and tear on the body from chronic stress.

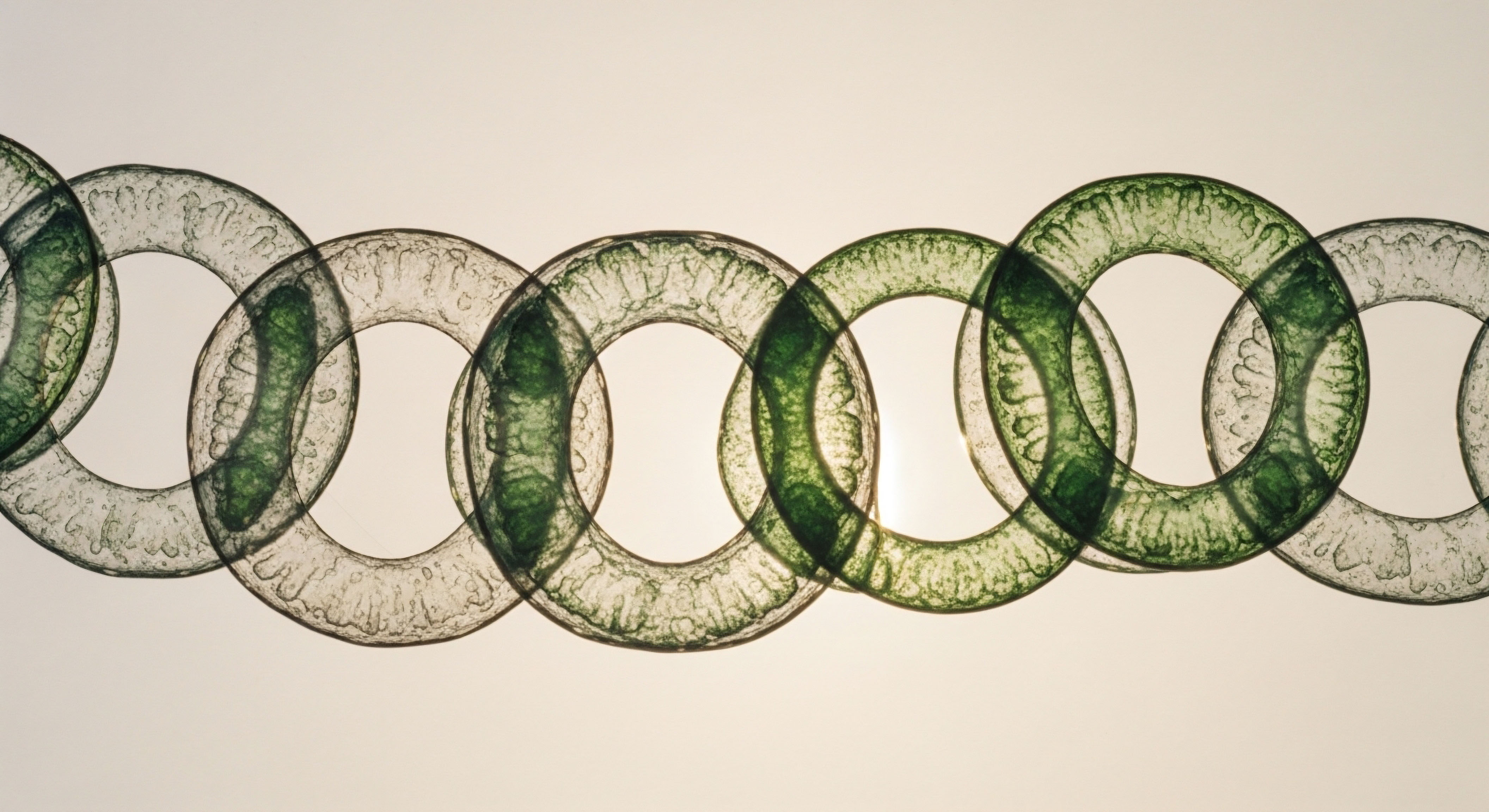

Allostatic overload is characterized by a dysregulation of the body’s primary stress mediators, including cortisol, catecholamines (epinephrine and norepinephrine), and inflammatory cytokines. This dysregulation can have cascading effects on multiple physiological systems, contributing to the pathogenesis of a wide range of chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and major depressive disorder.

The ADA’s voluntary requirement can therefore be viewed as a preventative measure, aimed at mitigating the iatrogenic potential of poorly designed wellness programs. By ensuring that participation is truly voluntary, the law helps to create a work environment that is more conducive to health and well-being, both physically and psychologically.

The ADA’s voluntary requirement for wellness programs can be seen as a crucial safeguard against the iatrogenic effects of chronic psychosocial stress in the workplace.

Psychoneuroendocrine Consequences of Coercive Wellness Programs

A coercive wellness Meaning ∞ Coercive wellness signifies the imposition of health behaviors through pressure, not voluntary choice. program, one in which participation is effectively mandated through substantial incentives or penalties, can be a potent source of chronic stress. The perception of a loss of autonomy and control is a well-established psychological stressor. This can lead to a state of learned helplessness, a condition characterized by a passive and apathetic response to aversive stimuli.

From a neuroendocrine perspective, this can manifest as a blunted cortisol response to acute stressors, a pattern that has been associated with a number of negative health outcomes, including increased inflammation and a greater susceptibility to autoimmune diseases.

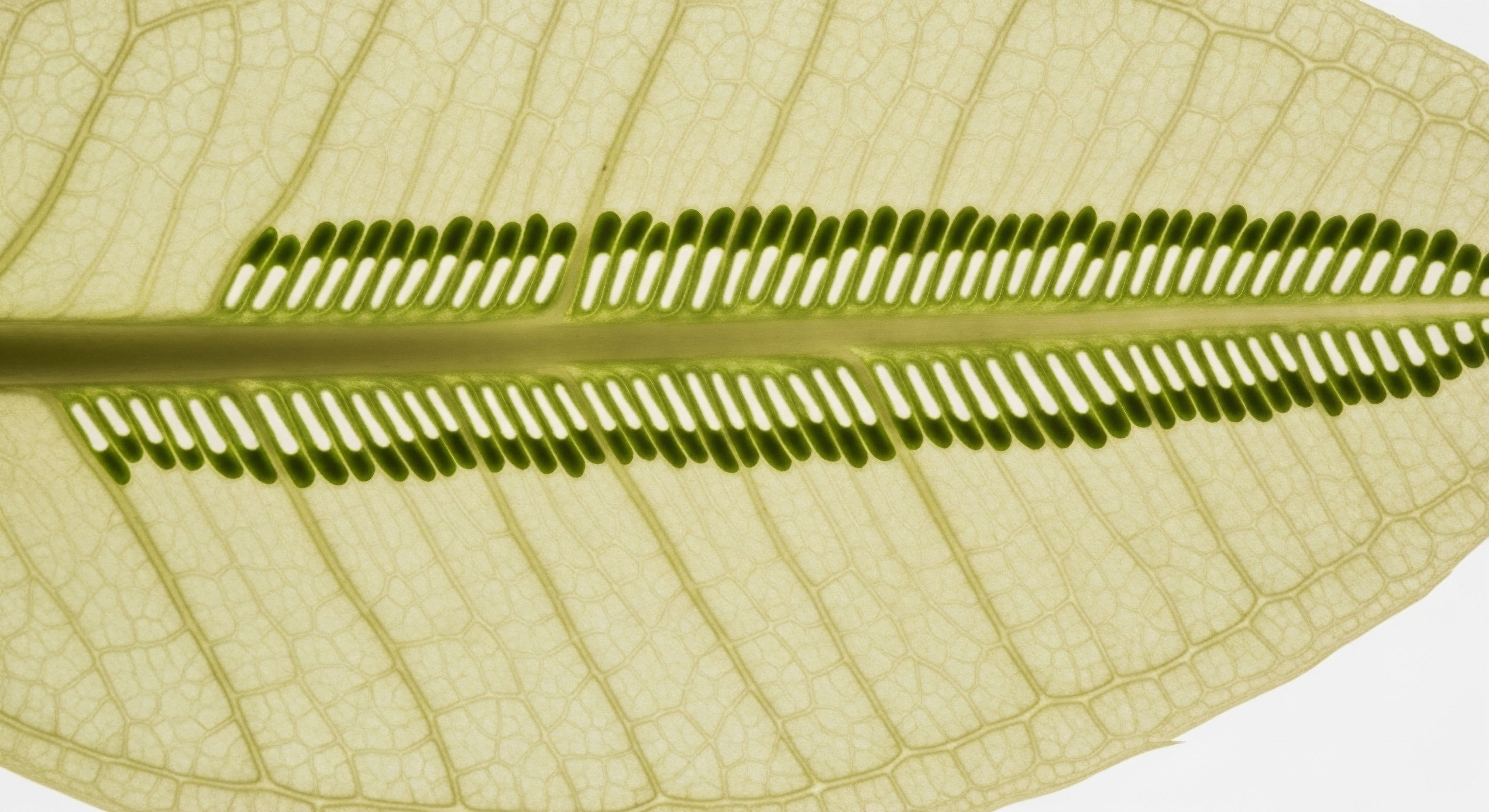

The impact of chronic stress on the HPA axis Meaning ∞ The HPA Axis, or Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis, is a fundamental neuroendocrine system orchestrating the body’s adaptive responses to stressors. is particularly well-documented. In the short term, the HPA axis is adaptive, helping the body to mobilize energy and respond to challenges. However, when the stressor is chronic and uncontrollable, the HPA axis can become dysregulated.

This can lead to either hypercortisolism (persistently high levels of cortisol) or hypocortisolism (abnormally low levels of cortisol). Both of these conditions are associated with a range of health problems. Hypercortisolism can lead to visceral obesity, insulin resistance, and immunosuppression. Hypocortisolism, on the other hand, is associated with fatigue, chronic pain, and an exaggerated inflammatory response.

| Physiological System | Potential Negative Impact | Underlying Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Endocrine System | HPA axis dysregulation, thyroid dysfunction, suppressed sex hormones. | Chronic activation of the stress response, leading to hormonal imbalances. |

| Metabolic System | Insulin resistance, visceral obesity, dyslipidemia. | Elevated cortisol and catecholamines, promoting gluconeogenesis and lipolysis. |

| Cardiovascular System | Hypertension, atherosclerosis, increased risk of myocardial infarction. | Increased sympathetic tone, endothelial dysfunction, and inflammation. |

| Immune System | Immunosuppression or immune dysregulation, increased susceptibility to infection and autoimmune disease. | Glucocorticoid-mediated suppression of cellular immunity and promotion of a pro-inflammatory state. |

The Impact on Metabolic Health

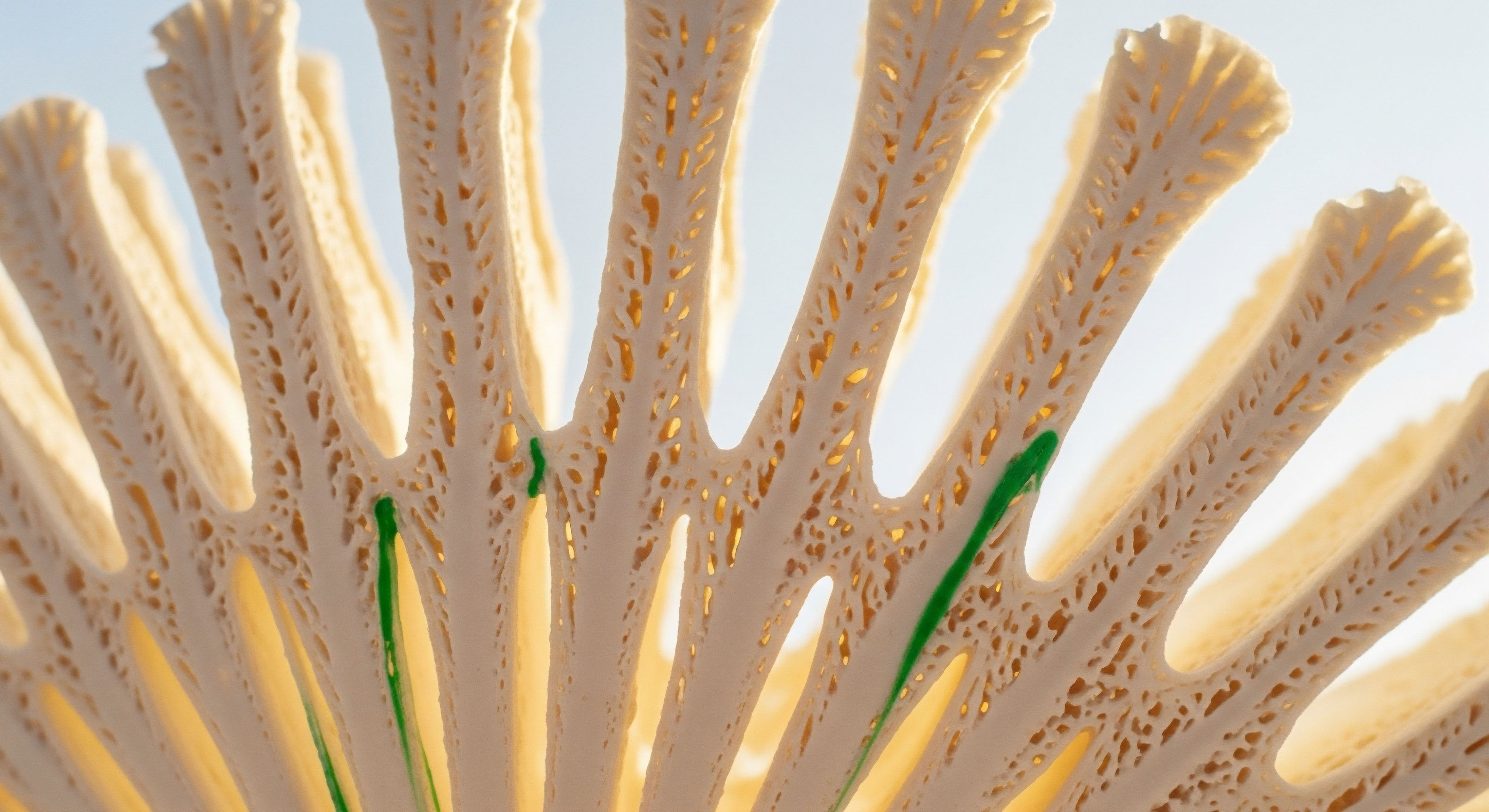

The link between chronic stress and metabolic dysfunction is particularly strong. The hormones released during the stress response, particularly cortisol and catecholamines, are designed to mobilize energy stores to fuel the “fight or flight” response. They do this by stimulating gluconeogenesis (the production of glucose in the liver) and lipolysis (the breakdown of fats).

In an acute stress situation, this is a highly adaptive response. However, when the stress is chronic, this sustained elevation of glucose and free fatty acids can lead to insulin resistance. The pancreas is forced to produce more and more insulin to keep blood glucose levels in check, and eventually, the beta cells of the pancreas can become exhausted, leading to the development of type 2 diabetes.

Chronic stress can also promote the accumulation of visceral adipose tissue (VAT), the fat that is stored around the organs in the abdominal cavity. VAT is more metabolically active than subcutaneous fat and is a major source of inflammatory cytokines.

This chronic low-grade inflammation is a key driver of insulin resistance and is associated with an increased risk of a wide range of chronic diseases. A coercive wellness program, by acting as a chronic stressor, can therefore directly contribute to the development of metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions that includes abdominal obesity, high blood pressure, high blood sugar, and abnormal cholesterol levels.

What Is the True Measure of a Program’s Success?

The prevailing model of wellness programs, with its emphasis on biometric screening and financial incentives, is based on a reductionist view of health. It assumes that health can be reduced to a set of numbers and that behavior can be manipulated through a system of rewards and punishments.

This approach fails to account for the complex interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors that determine an individual’s health and well-being. A more holistic and person-centered approach is needed, one that recognizes the importance of autonomy, intrinsic motivation, and a supportive social environment.

The success of a wellness program should be measured not by participation rates or changes in biometric data, but by its impact on the overall health and well-being of the workforce. This includes measures of physical health, mental health, and social well-being.

A truly successful program is one that empowers employees to take an active role in managing their own health, provides them with the resources and support they need to make lasting lifestyle changes, and creates a workplace culture that values and promotes well-being. The ADA’s voluntary requirement, by shifting the focus from compliance to empowerment, can be a catalyst for this type of transformative change.

- Focus on Intrinsic Motivation ∞ Design programs that tap into employees’ inherent desires for growth, health, and well-being.

- Promote a Growth Mindset ∞ Encourage a belief that abilities and health can be improved through dedication and hard work.

- Foster Social Connection ∞ Create opportunities for employees to connect with one another and build a supportive community around wellness.

References

- Braveman, P. & Gottlieb, L. (2014). The social determinants of health ∞ it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public health reports, 129(1_suppl2), 19-31.

- Chandola, T. Brunner, E. & Marmot, M. (2006). Chronic stress at work and the metabolic syndrome ∞ prospective study. Bmj, 332(7540), 521-525.

- McEwen, B. S. (2017). Neurobiological and systemic effects of chronic stress. Chronic stress (Thousand Oaks, Calif.), 1, 2470547017692328.

- Rozanski, A. Blumenthal, J. A. & Kaplan, J. (1999). Impact of psychological factors on the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and implications for therapy. Circulation, 99(16), 2192-2217.

- Sapolsky, R. M. (2005). The influence of social hierarchy on primate health. Science, 308(5722), 648-652.

- Steptoe, A. & Kivimäki, M. (2012). Stress and cardiovascular disease. Nature reviews cardiology, 9(6), 360-370.

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (2016). Questions and Answers about the EEOC’s Final Rule on Employer Wellness Programs and the Americans with Disabilities Act.

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (2016). Final Rule on Employer Wellness Programs and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act.

Reflection

Your health journey is a deeply personal one, a continuous dialogue between your body, your mind, and your environment. The knowledge that a truly supportive wellness program must honor your autonomy is a powerful first step. This understanding allows you to move beyond the passive receipt of information and become an active participant in your own well-being.

As you consider your own path, reflect on what it means to feel truly supported in your health goals. What resources would empower you? What kind of environment would allow you to flourish? The answers to these questions are unique to you, and they form the foundation of a personalized path to vitality. Your body has an innate wisdom. The journey to optimal health begins with learning to listen to it.

What Does Wellness Mean to You?

The concept of wellness is often defined by external metrics, but its true meaning is found within. It is a state of balance that encompasses not just your physical health, but also your mental, emotional, and spiritual well-being. Take a moment to consider what wellness looks like for you.

Is it the energy to pursue your passions? The resilience to navigate life’s challenges? The peace of mind that comes from living in alignment with your values? By defining your own vision of wellness, you can create a personalized roadmap for your health journey. This internal compass will guide you in making choices that are authentic and sustainable, leading you toward a life of greater vitality and fulfillment.

How Can You Cultivate a Supportive Environment?

Your environment plays a significant role in shaping your health and well-being. This includes your physical surroundings, your social connections, and the culture of your workplace. Consider the ways in which your current environment supports or hinders your health goals. Are there opportunities for movement and relaxation?

Do you have access to nutritious food? Do you feel a sense of connection and belonging? By identifying the areas where you need more support, you can begin to make small changes that can have a big impact on your overall well-being.

This might involve creating a dedicated space for mindfulness in your home, seeking out like-minded individuals who share your health interests, or advocating for a more supportive wellness culture in your workplace. Every step you take to cultivate a more nurturing environment is a step toward a healthier and more vibrant life.