Fundamentals

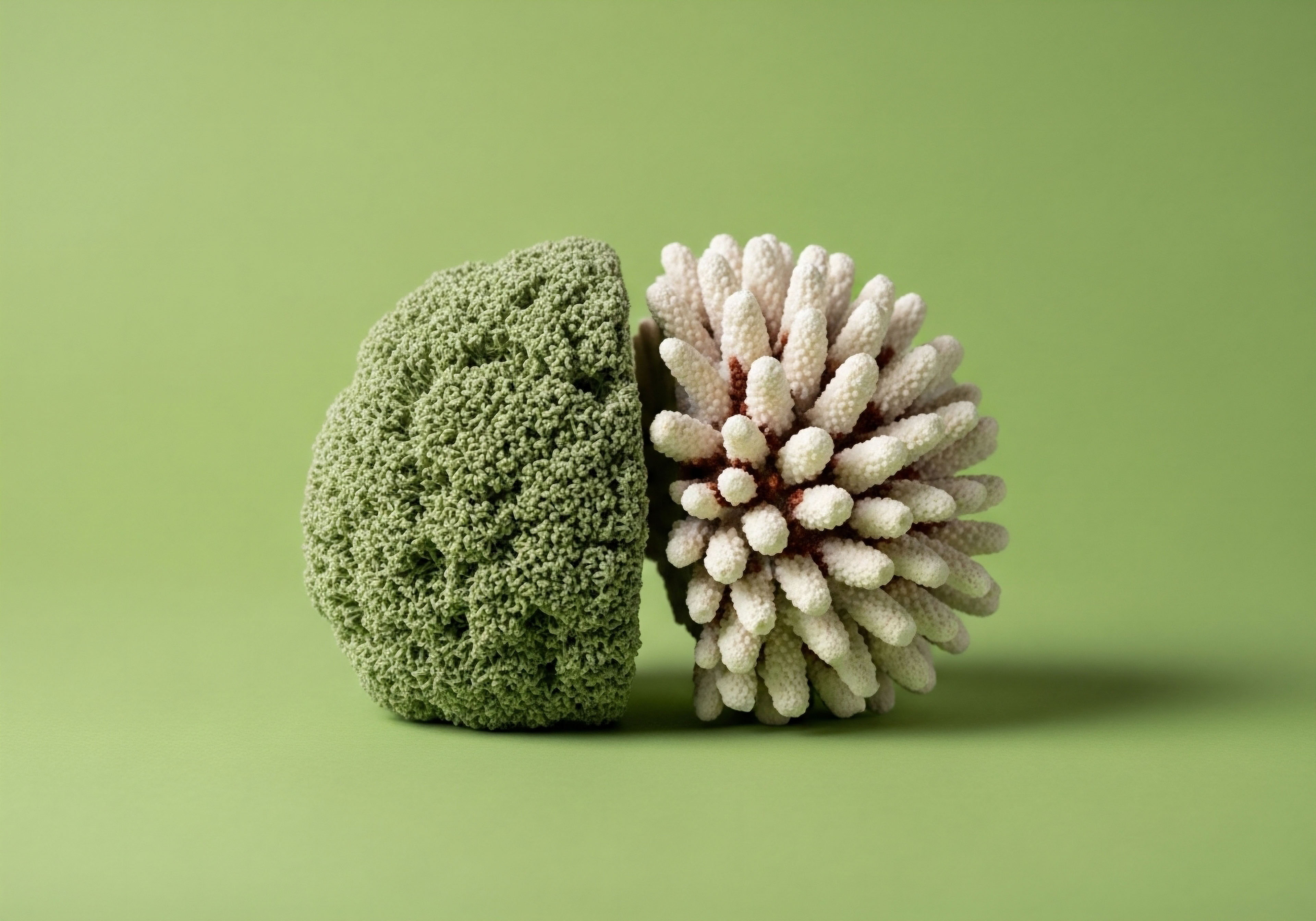

Your body is a finely tuned system, a constant conversation between cells and signals. When you feel a persistent sense of unease, a subtle but unshakeable fatigue, or a general decline in your vitality, it is often a sign that this internal communication network is experiencing interference.

These symptoms are your biology’s primary method of reporting a problem. They are data points. The sensation of being pressured into a workplace health screening, even one presented as a benefit, can itself become a source of this static.

The question of what makes a workplace wellness program “voluntary” under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) extends into the very real, physical domain of your endocrine system. The legal definition is concerned with preventing coercion. Your body’s definition of coercion is registered through the activation of its stress-response pathways.

A program’s design must be reasonable, intended to genuinely promote health rather than to simply harvest data or penalize individuals. This principle acknowledges that your participation should yield a tangible benefit to your well-being, such as personalized feedback or access to resources that help you interpret and act upon the information gathered.

A system that collects your sensitive health data without a clear, supportive purpose fails this test. It shifts from a tool for wellness into a mechanism for surveillance, and your physiology will register that shift. The experience of pressure, of a choice that is technically free but practically constrained, initiates a cascade of hormonal events.

This is a protective mechanism, ancient and automatic, designed to prepare you for a threat. When that threat is a persistent, low-grade institutional pressure, the protective mechanism becomes a chronic source of biological disruption.

A wellness program’s legal “voluntariness” is determined by its design and the absence of coercion, a standard that mirrors the body’s own need for safety to maintain biological balance.

The core of the ADA’s definition of a voluntary program rests on a simple premise you must not be required to participate, nor can you be punished for declining. You cannot be denied your health insurance or face any adverse employment action for choosing to keep your medical information private.

This legal safeguard is a recognition of the profound power imbalance that can exist in an employment relationship. Your health status, your genetic predispositions, and your personal biological rhythms are your own. A truly voluntary program respects this boundary absolutely. It presents an opportunity, an open door, without attaching a penalty to the decision to walk past it. The architecture of such a program is one of invitation, not demand.

This concept becomes more complex when incentives are introduced. An incentive is a reward for participation, and the law has sought to regulate how substantial these rewards can be. The central question is, at what point does a reward become so large that its refusal feels like a punishment?

A water bottle or a small gift card is an encouragement. A significant reduction in health insurance premiums, however, can feel like a mandate in disguise for many individuals navigating tight budgets. This is where the legal framework attempts to align with the lived reality of employees.

The withdrawal of a proposed rule that would have limited most incentives to a “de minimis” or modest value highlights the ongoing uncertainty in this area. For now, employers are advised to act with caution, recognizing that the line between a permissible incentive and a coercive measure is a source of legal ambiguity.

Your own internal “coercion detector” is far less ambiguous it is the feeling of being compelled, a feeling that your body translates into the language of stress hormones, disrupting the very wellness the program is meant to support.

Intermediate

To fully grasp the ADA’s stance on voluntary wellness programs, one must examine the specific mechanics of their implementation, particularly concerning medical inquiries and the structure of incentives. The ADA generally prohibits employers from asking disability-related questions or requiring medical examinations. An exception is made for voluntary employee health programs.

The architecture of this exception is built upon two pillars the program must be “reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease,” and participation must be genuinely voluntary. A program is considered reasonably designed when it provides feedback, follow-up, or advice based on the health information it collects.

A simple data-gathering exercise, where biometric results disappear into a corporate database without empowering the employee, fails this standard. This requirement is a clinical and ethical safeguard, ensuring the process is a diagnostic tool for the individual, not just a data source for the employer.

The concept of “voluntary” participation is where the system’s biochemistry intersects with legal statutes. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the agency that enforces the ADA, has clarified that employers cannot retaliate, intimidate, or coerce employees into participating. The introduction of financial incentives complicates this directive.

For years, a common practice was to align the incentive limit with the one permitted under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), which allowed up to 30% of the total cost of self-only health coverage (or 50% for tobacco-related programs). This could represent a substantial financial sum, thousands of dollars in some cases, creating a powerful inducement to share personal medical data.

The legal framework around wellness program incentives remains in flux, reflecting a deep-seated tension between promoting health and preventing economic coercion.

A critical legal development was a court ruling that vacated the EEOC’s 30% incentive limit, creating a period of significant regulatory uncertainty. The EEOC later proposed a new rule that would have drastically limited incentives for most programs to a “de minimis” amount, such as a water bottle, but this rule was subsequently withdrawn.

This sequence of events leaves employers in a precarious position. The core principle remains incentives cannot be so substantial as to be coercive. Yet, without a bright-line financial limit, the definition of “coercive” is subject to interpretation. This legal gray area places the onus on employers to evaluate their programs critically, considering not just the letter of the law but the spirit of non-coercion.

How Does Medical Confidentiality Intersect with Program Design?

A foundational requirement of any permissible wellness program under the ADA is the rigorous protection of medical information. The data collected, whether through a health risk assessment or a biometric screening, is subject to the ADA’s strict confidentiality rules.

Employers must provide a clear notice to employees explaining what information will be collected, who will have access to it, how it will be used, and how its privacy will be maintained. This information cannot be used to make employment decisions, and it must be stored separately from personnel files. This separation is a firewall, designed to prevent the sensitive data of an individual’s health from influencing decisions about their career.

From a clinical perspective, this confidentiality is paramount. Imagine a wellness screening reveals a male employee has testosterone levels indicative of hypogonadism or a female employee shows hormonal markers consistent with perimenopause. This is deeply personal information.

Its value lies in empowering that individual to have a conversation with their physician about potential therapeutic interventions, such as Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) or other hormonal optimization protocols. If the confidentiality of that data is compromised, or if the employee fears it might be, the program’s potential for good is nullified.

The fear of disclosure, of being judged or discriminated against based on a biomarker, can itself trigger a chronic stress response, undermining the goal of wellness. An employee cannot be required to waive these confidentiality protections as a condition of participation or for receiving an incentive.

Health-Contingent versus Participatory Programs

The regulatory framework distinguishes between two primary types of wellness programs, a distinction that has significant implications for incentive structures. Understanding this difference is essential for any analysis of what is permissible.

- Participatory Programs ∞ These programs require only that an individual participates to earn a reward. Examples include completing a health risk assessment or attending a seminar. Under HIPAA, there is no limit on the incentives for these types of programs, though the ADA’s anti-coercion principle still applies if medical information is collected.

- Health-Contingent Programs ∞ These programs require individuals to meet a specific health-related goal to earn an incentive. They are further divided into two subcategories:

- Activity-Only Programs ∞ These involve meeting a goal related to a physical activity, such as walking a certain number of steps per day.

- Outcome-Based Programs ∞ These require meeting a specific biometric target, such as achieving a certain cholesterol level or blood pressure reading. These are the most heavily regulated, as they directly tie financial outcomes to health status. For these programs, the 30% incentive limit under HIPAA is a key benchmark, and they must offer a reasonable alternative standard for individuals for whom it is medically inadvisable or impossible to meet the goal.

This distinction is central to the legal and ethical debate. A participatory program that simply screens for low testosterone and provides confidential resources is functionally different from an outcome-based program that penalizes an employee financially because their A1C levels remain in the prediabetic range despite their efforts. The latter model can create immense pressure, transforming a wellness initiative into a source of chronic anxiety and perceived failure, states that are biochemically counterproductive to achieving metabolic health.

| Program Type | Description | Governing Principle | Incentive Landscape |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participatory | Reward is earned for participation alone (e.g. filling out a questionnaire). | HIPAA places no limit on incentives. ADA’s anti-coercion rule applies if medical data is collected. | Legally flexible, but high incentives can still be viewed as coercive under the ADA. |

| Health-Contingent (Outcome-Based) | Reward is earned by meeting a specific health target (e.g. blood pressure goal). | HIPAA generally limits incentives to 30% of self-only coverage cost. Must offer reasonable alternative standards. | More heavily regulated due to the direct link between financial reward and health status. |

Academic

An academic deconstruction of the term “voluntary” within the context of the ADA and workplace wellness programs reveals a complex interplay of legal doctrine, behavioral economics, and psychoneuroendocrinology. The legal framework, primarily shaped by the ADA and enforced by the EEOC, establishes a floor for employee protections.

The biological reality, governed by the autonomic nervous system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, determines the actual human experience of these programs. The disjunction between the legal definition of non-coercion and the physiological manifestation of perceived coercion is where the most significant analysis lies.

The ADA’s allowance for “voluntary” medical examinations within a wellness program is an exception to its general prohibition against such inquiries. The legal scholarship surrounding this exception often centers on the “safe harbor” provision, which was originally intended to permit insurers to underwrite and classify risks.

The EEOC has consistently rejected the application of this safe harbor to wellness programs, arguing that the “voluntary” exception is the sole legitimate pathway. This stance is doctrinally significant. It signals that the purpose of data collection must be the promotion of health, not the assessment of risk for actuarial purposes.

A program designed to identify employees at high risk for chronic disease to adjust insurance premiums would likely fail the EEOC’s “reasonably designed” test. A program that identifies the same risk and provides confidential access to peptide therapy protocols for tissue repair, such as Pentadeca Arginate (PDA), or growth hormone secretagogues like Ipamorelin for metabolic optimization, could be seen as fulfilling that design, provided it adheres to strict confidentiality and non-discrimination standards.

The perception of coercion within a wellness program can activate the HPA axis, creating a chronic stress state that is antithetical to the program’s stated health objectives.

The central academic debate revolves around the incentive structure. Behavioral economics provides a powerful lens for this issue. The concept of “loss aversion,” articulated by Kahneman and Tversky, posits that individuals feel the pain of a loss approximately twice as powerfully as the pleasure of an equivalent gain.

In the context of wellness programs, this means a premium surcharge (a penalty for non-participation) is a much stronger motivator, and a much more potent source of perceived coercion, than a premium discount of the same amount (a reward for participation).

While legally structured as a reward, a large incentive can be framed by the employee as a loss if they fail to obtain it. An incentive of 30% of the cost of coverage, which could be several thousand dollars, is not merely an inducement; it is a powerful economic pressure that can compel an individual to disclose sensitive genetic or medical information against their better judgment.

This compelled disclosure, driven by financial necessity, is physiologically indistinguishable from a direct mandate for many individuals. It triggers the same vigilance, anxiety, and release of catecholamines and cortisol as an overt threat.

What Is the Neuroendocrine Impact of Perceived Coercion?

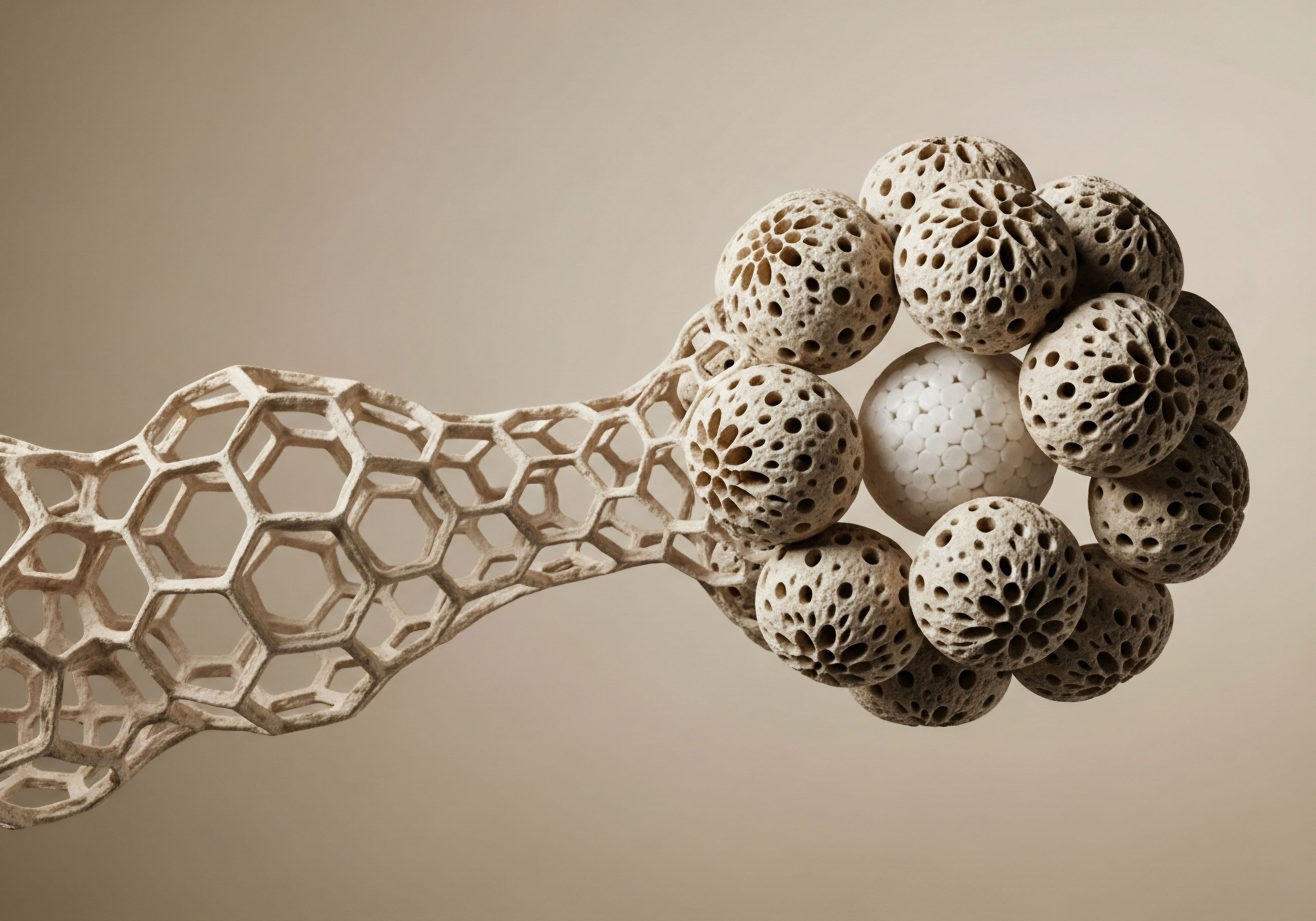

When an employee feels pressured to participate in a wellness program, the body’s stress-response system is engaged. This is not a subjective emotional state; it is a measurable physiological event. The amygdala, the brain’s threat detection center, signals the hypothalamus to activate the HPA axis.

This results in the release of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which stimulates the pituitary to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which in turn signals the adrenal glands to secrete cortisol. Simultaneously, the sympathetic nervous system releases epinephrine and norepinephrine.

This cascade has profound, systemic effects on the very health markers wellness programs aim to improve:

- Metabolic Disruption ∞ Cortisol promotes gluconeogenesis in the liver and increases insulin resistance in peripheral tissues. A state of chronic HPA axis activation, driven by the persistent anxiety of a coercive program, can therefore directly contribute to hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia, paradoxically increasing the risk for the metabolic syndrome the program may be designed to prevent.

- Endocrine Suppression ∞ Chronic cortisol elevation can suppress the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. In men, this can lead to decreased production of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), resulting in suppressed endogenous testosterone production. For men on a TRT protocol that includes Gonadorelin to maintain testicular function, this external stress can work against the therapy’s objectives. In women, chronic stress can disrupt the delicate pulsatile release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), leading to menstrual irregularities and exacerbating symptoms of perimenopause.

- Immune Dysregulation ∞ While acute cortisol release is anti-inflammatory, chronic elevation suppresses immune function, leaving the body more vulnerable to pathogens and potentially promoting a state of low-grade, chronic inflammation, a known driver of numerous degenerative diseases.

Therefore, a wellness program that is coercive in its implementation, even if legally compliant on paper, can become a direct iatrogenic cause of illness. The requirement for a program to be “reasonably designed to promote health” must be interpreted through a biopsychosocial lens. A program that induces a chronic stress response is, by definition, not reasonably designed to promote health.

| Biological System | Mechanism of Disruption | Clinical Implication | Relevance to Wellness Goals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic | Chronic cortisol elevation increases gluconeogenesis and insulin resistance. | Increased risk of hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome. | Directly contradicts goals of improving metabolic health markers like A1C and triglycerides. |

| Endocrine (HPG Axis) | Elevated cortisol suppresses GnRH, LH, and FSH production. | Suppression of testosterone in men and disruption of menstrual cycles in women. | Undermines hormonal balance, which is a key pillar of overall vitality and well-being. |

| Immune | Chronic cortisol exposure leads to suppression of cellular immunity. | Increased susceptibility to illness and promotion of chronic inflammation. | Works against the primary objective of disease prevention. |

References

- Apex Benefits. “Legal Issues With Workplace Wellness Plans.” 31 July 2023.

- Miller, Stephen. “EEOC Proposes ∞ Then Suspends ∞ Regulations on Wellness Program Incentives.” SHRM, 1 March 2021.

- Winston & Strawn LLP. “EEOC Issues Final Rules on Employer Wellness Programs.” 17 May 2016.

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. “Questions and Answers about EEOC’s Notice of Proposed Rulemaking on Employer Wellness Programs.” 20 April 2015.

- CDF Labor Law LLP. “EEOC Proposes Rule Related to Employer Wellness Programs.” 2015.

Reflection

The information presented here offers a framework for understanding the legal and biological dimensions of workplace wellness. Your own body, however, is the final arbiter of whether a program feels supportive or stressful. The subtle signals of anxiety, pressure, or unease are valuable data.

They are your personal feedback loop, informing you when an external system is misaligned with your internal need for autonomy and safety. True wellness is a state of physiological and psychological balance. Knowledge of the law provides the language to advocate for your rights.

An attunement to your own biology provides the wisdom to know when those rights are being compromised, regardless of the language used to frame the program. This understanding is the first step in actively managing your own health environment, ensuring that any path you choose is one that genuinely contributes to your vitality.

Glossary

workplace wellness

medical information

rule that would have

wellness programs

reasonably designed

equal employment opportunity commission

wellness program

testosterone replacement therapy

hormonal optimization

chronic stress

participatory programs

health-contingent programs

psychoneuroendocrinology

hpa axis