Fundamentals

You have embarked on a path of hormonal optimization, a precise and personal undertaking to restore your body’s intended signaling. You follow your protocol diligently, yet the results feel inconsistent, perhaps less profound than anticipated. This common experience is frequently rooted in a biological conversation happening deep within your body, a conversation where your diet holds a primary speaking role.

The food you consume does far more than provide simple energy; it actively directs the metabolic processing and ultimate availability of the therapeutic hormones you introduce. Understanding this relationship is the first step toward transforming your protocol from a simple instruction into a dynamic, responsive partnership with your own physiology.

The journey of a hormone administered orally begins in the gastrointestinal tract and proceeds directly to the liver. This pathway, known as first-pass metabolism, is a critical checkpoint where a significant portion of the hormone can be deactivated before it ever reaches systemic circulation.

Your dietary choices are the primary regulators of this checkpoint. For instance, the composition of your meals, particularly their fat and fiber content, directly modifies the environment in which hormones are absorbed. Saturated fats can diminish the body’s capacity to metabolize estrogen effectively, creating a form of biological static.

Conversely, specific types of dietary fiber can bind to hormones in the gut, facilitating their excretion and thereby lowering the circulating dose. This is a direct, mechanical influence your food choices exert upon the precise medications you are taking.

Your nutritional intake creates the biochemical environment that determines how effectively your body can absorb and utilize hormone replacement therapy.

The Role of Macronutrients in Hormonal Signaling

Your body’s response to hormonal therapy is deeply intertwined with the balance of proteins, fats, and carbohydrates you consume. Each macronutrient class initiates a cascade of metabolic signals that can either support or interfere with the action of therapeutic hormones. Appreciating these connections allows you to architect a diet that works in concert with your wellness protocol.

Proteins as Foundational Building Blocks

Proteins are fundamental for the synthesis of enzymes and transport molecules that are essential for hormone function. Adequate intake of high-quality protein from sources like lean meats, fish, and legumes ensures your body has the necessary substrates to manage hormonal pathways.

For individuals on testosterone replacement therapy (TRT), sufficient protein is also necessary to support the anabolic signaling that leads to muscle tissue repair and growth. A diet deficient in protein can undermine the very goals of the therapy itself, as the body will lack the raw materials to respond to the hormonal prompts.

Fats and the Synthesis of Hormones

Dietary fats are direct precursors to many hormones and are vital for the health of cell membranes, which contain hormone receptors. The type of fat consumed is of particular importance. Omega-3 fatty acids, found in fish and certain nuts, possess inflammation-modulating properties that can create a more favorable systemic environment for hormone action.

In contrast, a diet high in certain saturated and trans fats can promote an inflammatory state, which may blunt the sensitivity of hormone receptors and interfere with metabolic processes, including the metabolism of estrogen. Your selection of dietary fats sends a powerful message to your endocrine system, influencing everything from cellular sensitivity to systemic inflammation.

What Are the Initial Dietary Adjustments for HRT?

Making initial dietary adjustments involves a strategic selection of foods that support hormonal equilibrium and bone density, which can be affected during hormonal transitions. The goal is to provide the body with the nutrients it needs to complement the therapeutic effects of HRT.

- Phytoestrogens These plant-based compounds, found in soy products, legumes, and certain seeds, possess a structure that allows them to interact with estrogen receptors. While they are not hormones themselves, their presence can modulate the body’s estrogenic environment. Including sources like tofu, chickpeas, and flaxseed can be a supportive measure.

- Calcium-Rich Foods Hormonal changes, particularly in menopausal women, can accelerate the loss of bone mineral density. A diet rich in calcium is a foundational protective measure. Sources include low-fat dairy products, fortified juices, and leafy green vegetables. The recommended daily intake is a clinical benchmark to aim for to preserve skeletal integrity.

- High-Quality Protein Ensuring an adequate supply of protein is essential for maintaining muscle mass and metabolic rate, both of which can be affected by hormonal shifts. Lean meats, poultry, fish, and eggs are excellent sources that support the body’s structural and metabolic needs during therapy.

Intermediate

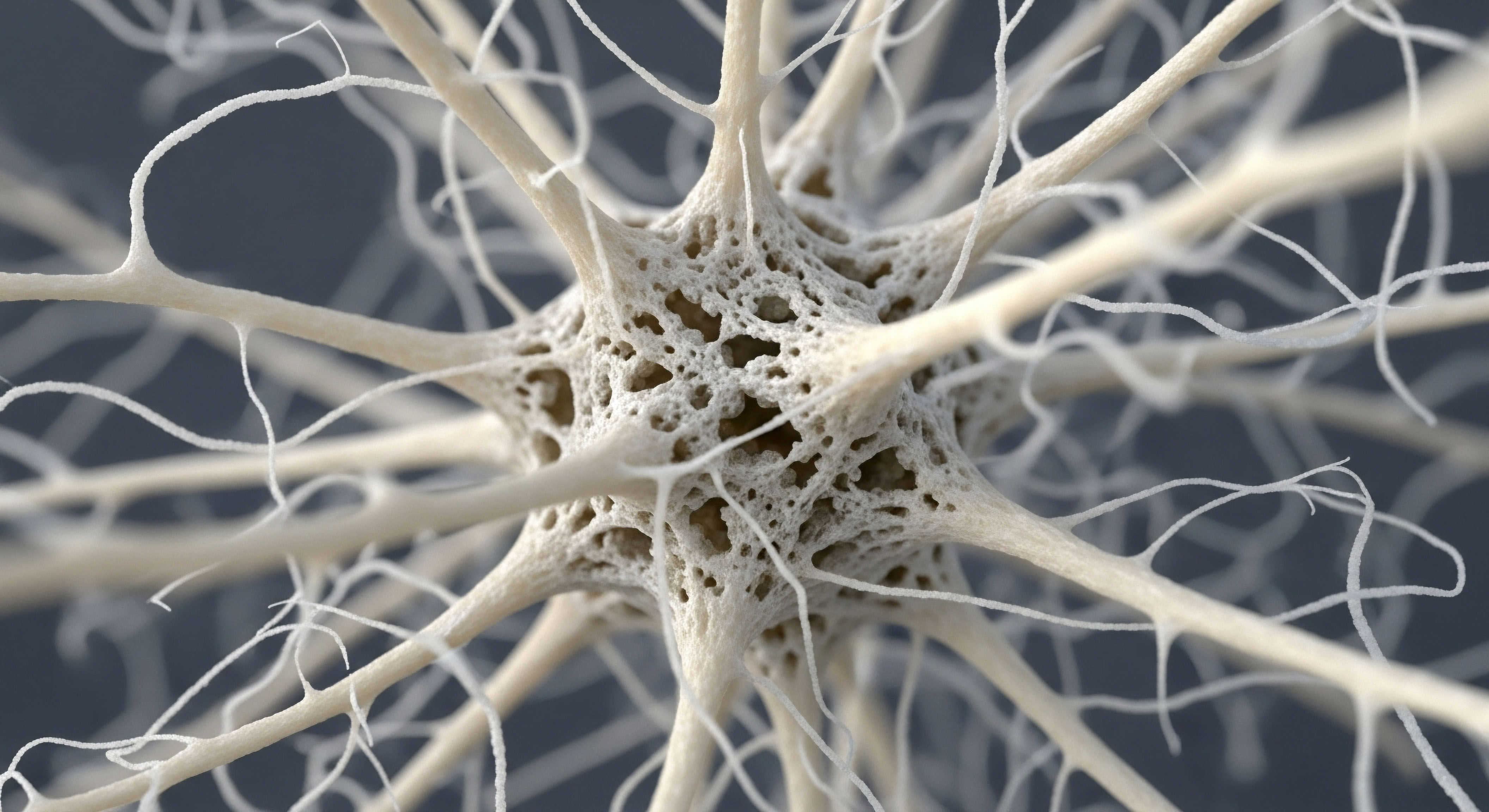

Moving beyond foundational concepts, we arrive at the sophisticated interplay between your gut microbiome and your endocrine system. This internal ecosystem, composed of trillions of microorganisms, is an active metabolic organ. A specific subset of these microbes, collectively termed the “estrobolome,” produces enzymes that metabolize estrogens.

The health and diversity of your estrobolome can significantly influence the levels of circulating estrogens, thereby affecting the efficacy of your hormonal protocol. A diet rich in processed foods and low in fiber can disrupt this delicate microbial balance, leading to suboptimal hormone metabolism. Conversely, a diet abundant in diverse plant fibers, prebiotics, and probiotics nurtures a robust microbiome, promoting healthy estrogen circulation and detoxification.

The route of administration for your hormonal therapy is a key determinant of how your diet will interact with it. Oral hormones, as we have seen, are subject to the digestive and hepatic gauntlet of first-pass metabolism. Transdermal applications, such as patches, gels, or subcutaneous injections of Testosterone Cypionate, largely bypass this route.

By delivering the hormone directly into the bloodstream, they avoid the initial metabolic breakdown in the liver. This makes the therapeutic dose more predictable and less subject to direct interference from dietary components within the gut. However, your overall metabolic health, which is governed by your long-term dietary patterns, still dictates how your tissues will respond to these hormones.

Systemic inflammation, insulin sensitivity, and nutrient status all shape the cellular environment and receptor sensitivity, meaning diet remains a powerful modulating factor for all forms of hormonal therapy.

The method of hormone delivery, whether oral or transdermal, alters the specific ways in which your diet influences therapeutic outcomes.

The Gut Microbiome a Master Regulator

The community of bacteria residing in your gut does more than aid digestion; it actively participates in regulating your hormonal milieu. The estrobolome, for example, produces an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase, which can reactivate previously conjugated (deactivated) estrogens that are awaiting excretion.

A healthy, balanced microbiome maintains a normal level of this enzyme, allowing for proper estrogen clearance. An imbalanced microbiome, or dysbiosis, can lead to either an excess or a deficit of beta-glucuronidase activity. This can cause estrogen levels to become undesirably high or low, interfering with the steady state your HRT protocol aims to achieve.

Your dietary choices, particularly the consumption of fiber-rich and fermented foods, are the most direct way to cultivate a healthy microbiome and, by extension, a well-regulated estrobolome.

How Does Diet Influence Different HRT Protocols?

The specific hormonal protocol you are on has unique interactions with your diet. For men on TRT, a diet that supports lean mass and controls inflammation is paramount. For women navigating perimenopause, managing blood sugar and supporting phytoestrogen intake can be beneficial. Understanding these nuances allows for a more tailored nutritional strategy.

| HRT Protocol | Primary Dietary Goal | Key Nutritional Components | Foods to Emphasize |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male TRT (Testosterone Cypionate) | Support Lean Muscle Mass & Manage Estrogen | High-Quality Protein, Zinc, Omega-3 Fatty Acids, Cruciferous Vegetables | Lean Beef, Salmon, Oysters, Broccoli, Cauliflower |

| Female HRT (Estradiol & Progesterone) | Manage Vasomotor Symptoms & Support Bone Health | Phytoestrogens, Calcium, Vitamin D, Fiber | Soy, Lentils, Fortified Dairy, Leafy Greens, Fatty Fish |

| Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy | Optimize Insulin Sensitivity & Support Tissue Repair | Complex Carbohydrates, Lean Protein, Antioxidants | Quinoa, Chicken Breast, Berries, Spinach |

Nutrient Deficiencies and Hormonal Disruption

Specific micronutrient deficiencies can impede the body’s ability to properly synthesize and metabolize hormones, creating friction against your therapeutic protocol. These are not rare occurrences; modern diets often lack sufficient levels of key vitamins and minerals that are essential for endocrine function. Identifying and addressing these gaps is a critical step in optimizing your outcomes.

- Vitamin D This pro-hormone is essential for immune function and insulin sensitivity, and it works synergistically with sex hormones. Deficiency is widespread and can dampen the body’s response to HRT. Sun exposure and supplementation are often necessary to maintain adequate levels.

- Magnesium Involved in over 300 enzymatic reactions, magnesium plays a vital role in blood glucose control and nervous system regulation. It can help mitigate some side effects associated with hormonal shifts, such as sleep disturbances and anxiety. Leafy greens, nuts, and seeds are excellent sources.

- B Vitamins The B-complex vitamins, particularly B6 and B12, are cofactors in neurotransmitter synthesis and hormone metabolism. They are critical for managing the mood and energy fluctuations that can accompany hormonal transitions. Deficiencies can lead to symptoms that are often mistakenly attributed solely to the hormonal imbalance itself.

Academic

A granular examination of the diet-hormone interface requires an understanding of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) superfamily of enzymes. These proteins, concentrated primarily in the liver but also present in the intestinal wall, are the principal machinery for metabolizing a vast array of compounds, including therapeutic hormones like estradiol and testosterone.

The activity of these enzymes is not static; it is directly modulated by various dietary components. For example, compounds in grapefruit juice are potent inhibitors of the CYP3A4 enzyme. If a patient consumes grapefruit while taking an oral hormone metabolized by CYP3A4, the enzyme’s inhibition can lead to significantly higher, potentially unsafe, levels of the hormone in the bloodstream.

Conversely, compounds in cruciferous vegetables like broccoli and brussels sprouts can induce other CYP enzymes, potentially accelerating the breakdown of hormones and reducing their therapeutic effect. This creates a highly individualized metabolic landscape, where a food that is benign for one person could fundamentally alter the pharmacokinetics of a medication for another.

This variability is further compounded by genetic polymorphisms. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the genes that code for CYP enzymes are common in the population. An individual may have a genetically faster or slower version of a particular enzyme, which establishes their baseline metabolic rate for certain hormones.

When you overlay dietary influences upon this unique genetic foundation, the complexity becomes apparent. This is the biological basis for why standardized HRT protocols can yield such varied results among individuals. A personalized therapeutic strategy, therefore, must consider this intricate triad of hormone, diet, and genetics. Clinical assessment may one day routinely involve genetic testing to predict metabolic tendencies, allowing for the prescription of both a hormone protocol and a precisely tailored dietary plan to ensure optimal absorption and response.

The interaction between dietary compounds, hepatic enzymes, and individual genetic variations dictates the precise pharmacokinetic profile of hormone therapy.

Enterohepatic Circulation and Dietary Fiber

The liver conjugates, or deactivates, hormones by attaching a molecule (like glucuronic acid) to make them water-soluble for excretion via the bile. This mixture enters the intestines. Here, certain gut bacteria can cleave off the attached molecule, liberating the hormone to be reabsorbed back into the bloodstream.

This process is called enterohepatic circulation, and it effectively creates an internal recycling system that can prolong the life of a hormone in the body. Soluble fiber, found in foods like oats, apples, and beans, plays a direct role in interrupting this cycle.

It forms a gel-like substance in the gut that binds to the conjugated hormones in the bile, preventing their reactivation and ensuring their final excretion. A diet high in soluble fiber can therefore lower the body’s total exposure to both endogenous and exogenous estrogens by preventing their reabsorption.

Can Specific Foods Alter Hormone Metabolism?

Certain foods contain bioactive compounds that have a documented ability to influence the enzymatic pathways responsible for hormone breakdown. This is not a theoretical concern; it is a practical pharmacological reality that has implications for anyone on a hormonal protocol. Acknowledging these interactions is a component of a sophisticated and safe therapeutic approach.

| Bioactive Compound | Dietary Source | Metabolic Influence | Potential Effect on HRT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naringin & Furanocoumarins | Grapefruit, Seville Oranges | Inhibits CYP3A4 enzyme activity in the intestines and liver. | Increases bioavailability and circulating levels of orally administered estrogens and testosterone. |

| Indole-3-Carbinol (I3C) | Broccoli, Cabbage, Kale | Induces Phase I and Phase II detoxification enzymes, including CYP1A2. | May accelerate the clearance of estrogens, potentially altering the required therapeutic dose. |

| Resveratrol | Grapes, Berries, Peanuts | Modulates estrogen receptor activity and influences aromatase enzyme expression. | Can exert weak estrogenic or anti-estrogenic effects, depending on the cellular context. |

| Lignans | Flaxseeds, Sesame Seeds | Metabolized by gut bacteria into enterolactone and enterodiol, which have weak estrogenic activity. | Can compete with estradiol at receptor sites, potentially modulating the overall estrogenic signal. |

The clinical implications of these interactions are significant. For a man on a TRT protocol that includes an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole, a diet that simultaneously induces aromatase could be working at cross-purposes with the medication.

Similarly, for a postmenopausal woman on low-dose estradiol, a diet that dramatically accelerates estrogen clearance could render the therapy less effective for symptom management or bone density preservation. The future of personalized medicine lies in understanding these multi-layered interactions, moving from a one-size-fits-all model to one that is biochemically and genetically bespoke.

References

- Nova Pharmacy. “HRT diet.” Nova Pharmacy, Accessed 29 July 2024.

- Berendsen, A. M. et al. “Differential Dietary Nutrient Intake according to Hormone Replacement Therapy Use ∞ An Underestimated Confounding Factor in Epidemiologic Studies?” American Journal of Epidemiology, vol. 167, no. 9, 2008, pp. 1121-1129.

- Ganesan, Kavitha, and Abdul H. Siddiqui. “Hormone Replacement Therapy.” StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, 2024.

- Shadoan, M. K. and J. R. Kaplan. “The effects of hormone replacement therapy on carbohydrate metabolism and cardiovascular risk factors in surgically postmenopausal cynomolgus monkeys.” Metabolism, vol. 45, no. 10, 1996, pp. 1285-92.

- The British Menopause Society. “Measurement of serum estradiol in the menopause transition.” The British Menopause Society, 2023.

Reflection

You now possess a deeper awareness of the intricate and constant dialogue between your nutritional choices and your body’s hormonal state. The information presented here provides a map of the underlying biological terrain. It details how the molecules in your food communicate with the enzymes in your liver, how fiber influences clearance pathways, and how the very route of your therapy alters these interactions.

This knowledge serves a distinct purpose ∞ it shifts the locus of control. The feelings of frustration or confusion that can arise when a protocol does not meet expectations can be replaced by a sense of informed curiosity. Your personal health journey is a unique dataset, an ongoing experiment where you are the primary investigator.

The next step is to observe your own responses, to notice the subtle shifts that accompany your dietary modifications, and to use this self-knowledge to refine the conversation you are having with your own body. This path is one of collaboration between you, your clinical guide, and the profound intelligence of your own physiology.

Glossary

first-pass metabolism

phytoestrogens

estrobolome

hormone metabolism

testosterone cypionate

cytochrome p450

enterohepatic circulation