Fundamentals

The conversation about hormonal health often begins with a feeling. It could be a subtle shift in energy, a change in physical resilience, or a general sense that your body’s internal calibration is off. These experiences are valid and deeply personal, and they are frequently the first signal that the intricate communication network within your body requires attention.

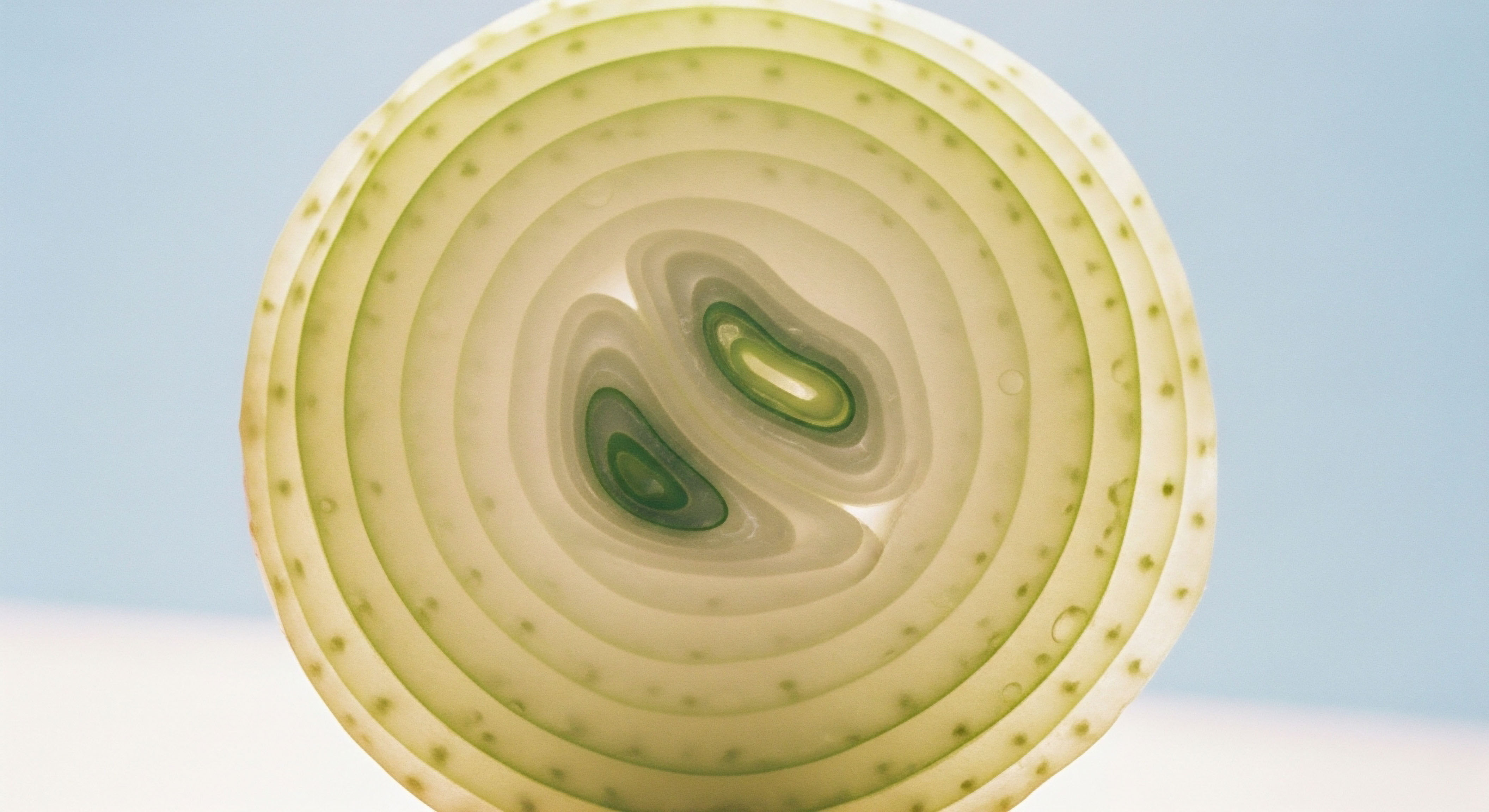

At the center of this network is the endocrine system, a collection of glands that produces hormones. These chemical messengers travel through your bloodstream, instructing tissues and organs on what to do, how to grow, and how to function. Understanding this system is the first step toward reclaiming your vitality.

Cardiovascular health is profoundly linked to this hormonal symphony. Your heart, arteries, and veins are not passive tubes; they are active, dynamic tissues lined with receptors that listen for hormonal signals. These signals influence everything from the flexibility of your blood vessels to the way your body processes fats and sugars.

When hormonal balance is optimal, this system works efficiently, maintaining vascular tone and metabolic wellness. When key hormones decline or become imbalanced, the system can lose its fine-tuned regulation, contributing to the very symptoms that initiated your concern.

The Central Role of Steroid Hormones

Two of the most significant messengers in this context are testosterone and estrogen. While commonly associated with male and female characteristics, respectively, both are vital for all adults. They belong to a class of hormones derived from cholesterol, and their molecular structures allow them to pass through cell membranes and directly influence a cell’s DNA, effectively rewriting its instructions for the day. This powerful mechanism is how they regulate so many aspects of our physiology.

Testosterone, for instance, contributes to the maintenance of lean muscle Meaning ∞ Lean muscle refers to skeletal muscle tissue that is metabolically active and contains minimal adipose or fat content. mass. A healthy amount of muscle is metabolically active, helping to regulate blood sugar and improve insulin sensitivity. This hormone also has direct effects on blood vessels, promoting vasodilation, which is the widening of arteries to improve blood flow and lower pressure.

Estrogen is similarly essential for vascular health. It supports the health of the endothelium, the delicate inner lining of your blood vessels, and plays a role in managing cholesterol levels and preventing inflammation within the artery walls.

A decline in key hormones directly impacts the body’s ability to regulate cardiovascular function and metabolic stability.

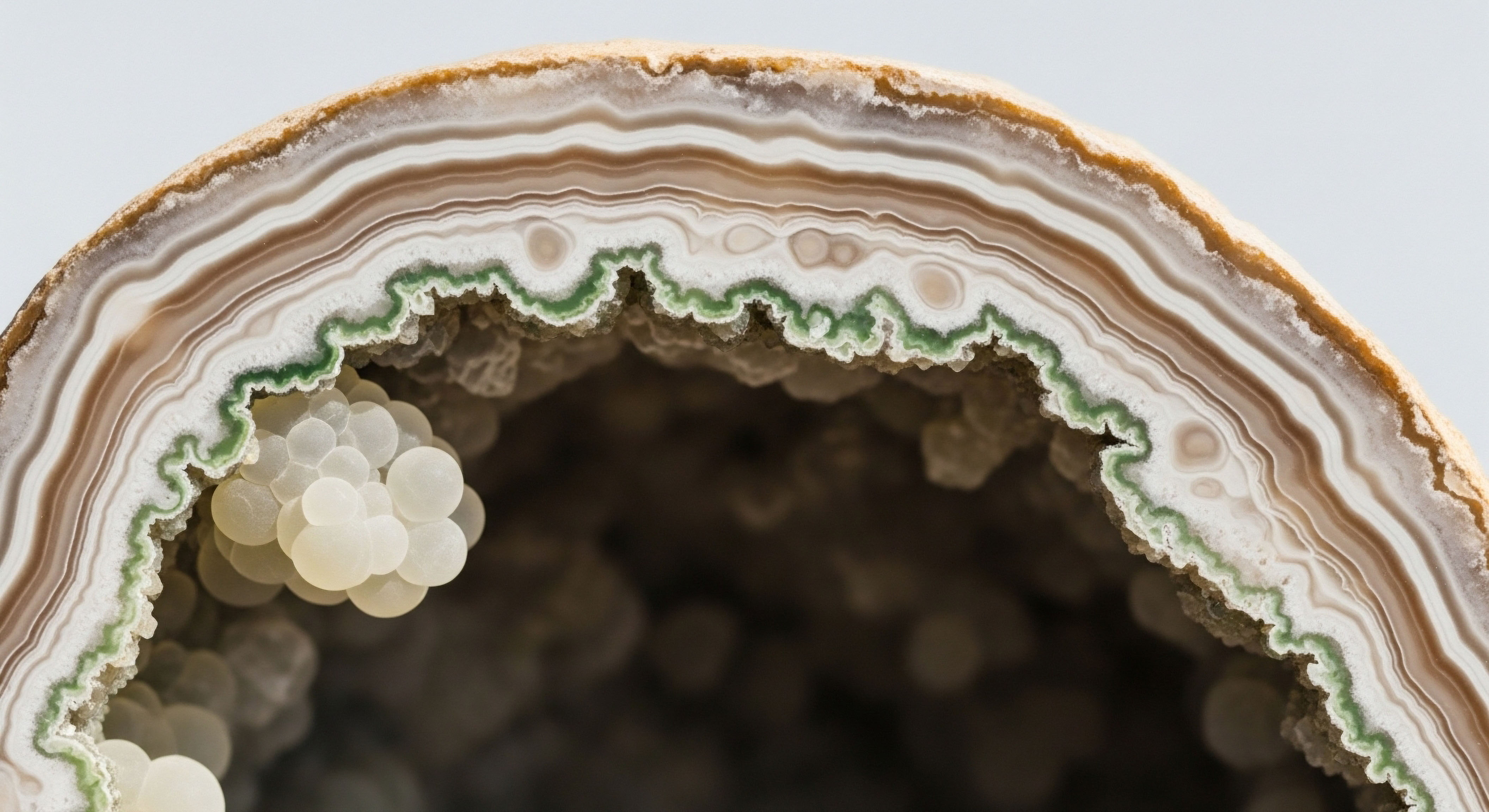

The aging process naturally leads to a gradual decline in the production of these hormones. For men, this manifests as andropause, with a steady drop in testosterone. For women, menopause Meaning ∞ Menopause signifies the permanent cessation of ovarian function, clinically defined by 12 consecutive months of amenorrhea. brings a more precipitous fall in estrogen and progesterone, alongside a decline in testosterone. This hormonal shift is a critical inflection point for cardiovascular health.

The loss of these protective signals can accelerate the development of conditions like atherosclerosis, where plaque builds up in the arteries, and can worsen metabolic markers across the board.

Why Consider Hormonal Interventions?

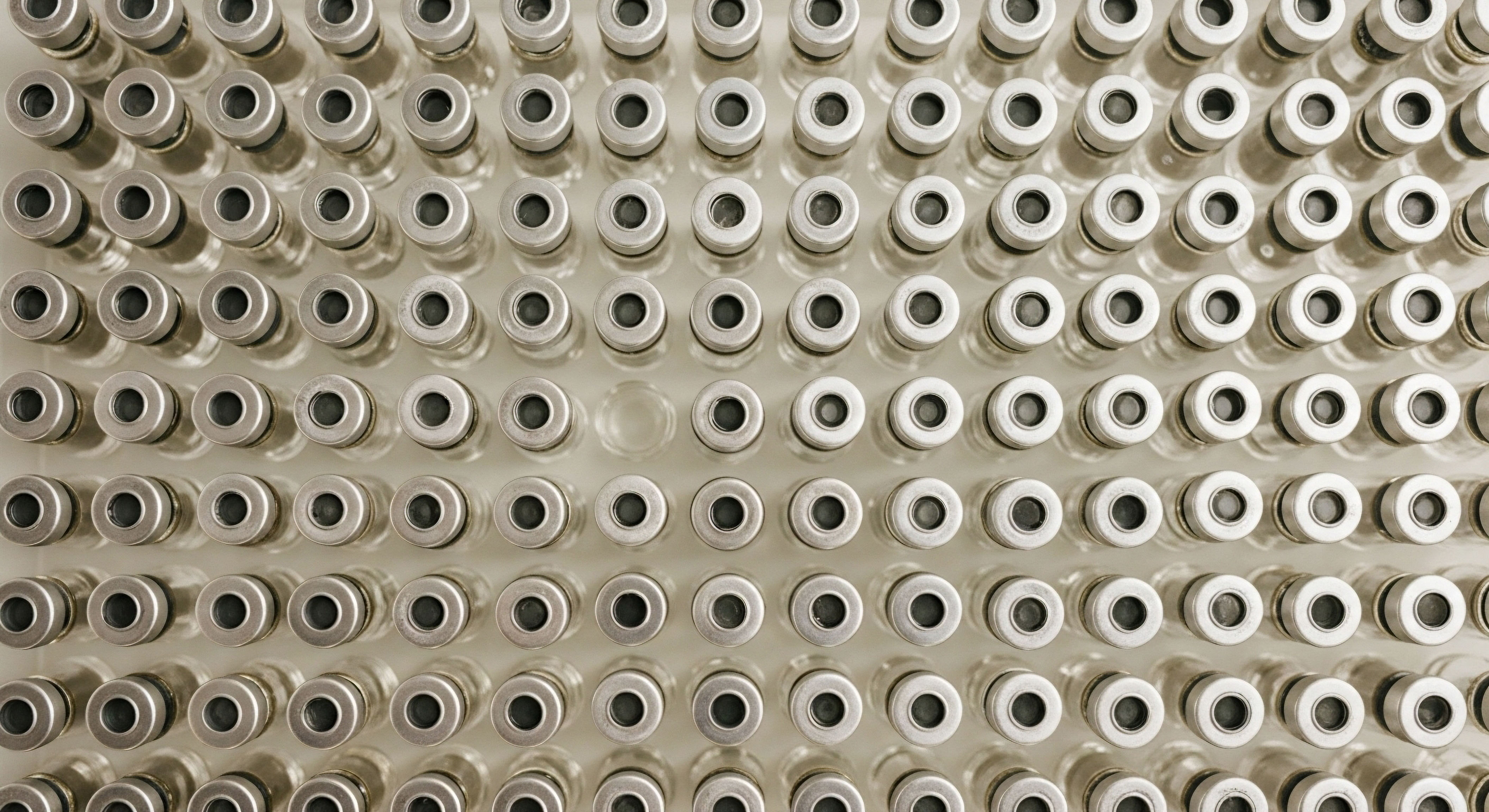

The goal of any hormonal intervention is to restore the body’s internal communication system to a more youthful and functional state. It is about providing the body with the signals it needs to maintain its own health. Low-dose testosterone therapy Low-dose testosterone therapy can restore female vitality, enhancing mood, energy, libido, and body composition by recalibrating endocrine balance. is one such intervention, designed to replenish testosterone to a physiological level that supports muscle, metabolism, and vascular function.

This approach stands alongside other hormonal strategies, such as estrogen replacement for postmenopausal women or supplementation with hormonal precursors like DHEA. Each intervention targets a different part of the endocrine web, and understanding their distinct mechanisms is key to comprehending how they compare in the context of cardiovascular wellness. The journey begins with recognizing that your symptoms are real and that they have a biological basis, a basis that can be understood and addressed with precision.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational understanding of hormones, the clinical application of hormonal therapies requires a more detailed map of their mechanisms and outcomes. When considering low-dose testosterone Meaning ∞ Low-dose testosterone refers to therapeutic administration of exogenous testosterone at concentrations below full physiological replacement. therapy, it is essential to place it in context with other hormonal interventions, each with a unique physiological footprint. The objective is to recalibrate a complex system, and each tool offers a different leverage point.

Low Dose Testosterone Therapy a Closer Look

Low-dose testosterone therapy Meaning ∞ A medical intervention involves the exogenous administration of testosterone to individuals diagnosed with clinically significant testosterone deficiency, also known as hypogonadism. in both men and women aims to restore circulating levels of this hormone to a range associated with optimal health. The cardiovascular benefits are thought to stem from several interconnected actions. Testosterone interacts with androgen receptors located on the endothelial cells lining blood vessels and on the vascular smooth muscle cells within artery walls.

This interaction can promote the production of nitric oxide, a potent vasodilator that helps relax arteries, improve blood flow, and maintain healthy blood pressure.

Furthermore, testosterone influences body composition by favoring the development of lean muscle mass Meaning ∞ Lean muscle mass represents metabolically active tissue, primarily muscle fibers, distinct from adipose tissue, bone, and water. over adipose tissue. This shift is metabolically advantageous. Muscle tissue is a primary site for glucose uptake, and by preserving it, testosterone therapy can improve insulin sensitivity.

Improved insulin sensitivity Meaning ∞ Insulin sensitivity refers to the degree to which cells in the body, particularly muscle, fat, and liver cells, respond effectively to insulin’s signal to take up glucose from the bloodstream. means the body can manage blood sugar more effectively, reducing a key risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Recent large-scale studies, such as the TRAVERSE trial, have provided reassuring data, showing that testosterone replacement therapy in men with hypogonadism did not increase the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events compared to placebo.

Each hormonal protocol offers a distinct mechanism of action, targeting different aspects of the cardiovascular and metabolic systems.

Estrogen Therapy the Timing Hypothesis

Estrogen replacement therapy, particularly for postmenopausal women, has a more complex history. Early observational studies suggested a strong cardioprotective effect. However, the landmark Women’s Health Initiative Meaning ∞ The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) was a large, long-term national health study by the U.S. (WHI) trial initially reported an increased risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in women taking a combination of conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) and medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA). This led to a dramatic shift in clinical practice.

Subsequent analyses of the WHI data, however, revealed a critical factor ∞ age and time since menopause. This gave rise to the “timing hypothesis.” This hypothesis suggests that women who begin estrogen therapy Meaning ∞ Estrogen therapy involves the controlled administration of estrogenic hormones to individuals, primarily to supplement or replace endogenous estrogen levels. closer to the onset of menopause (e.g.

in their 50s) may indeed receive cardiovascular benefits, potentially because their arteries are still relatively healthy and receptive to estrogen’s protective effects. In contrast, initiating therapy a decade or more after menopause, when underlying atherosclerosis Meaning ∞ Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by the progressive accumulation of lipid and fibrous material within the arterial walls, forming plaques that stiffen and narrow blood vessels. may already be present, could have neutral or even detrimental effects.

The estrogen-only arm of the WHI, conducted in women who had a hysterectomy, did not show an increased risk of heart disease, further highlighting the complexity and the potential role of the progestin component in the initial findings.

What Are the Other Hormonal Players?

Beyond testosterone and estrogen, other hormonal interventions Meaning ∞ Hormonal interventions refer to the deliberate administration or modulation of endogenous or exogenous hormones, or substances that mimic or block their actions, to achieve specific physiological or therapeutic outcomes. target the endocrine system from different angles. Understanding their distinct approaches is crucial for a comprehensive comparison.

- Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) ∞ DHEA is a precursor hormone produced by the adrenal glands, which the body can convert into testosterone and estrogen. The idea behind DHEA supplementation is to provide the raw materials for the body to produce its own hormones. Levels of DHEA naturally decline with age. Some studies suggest that DHEA may have direct beneficial effects on the vasculature, such as improving endothelial function and acting as a vasorelaxant. However, clinical trial results have been mixed. Some research has shown little to no effect on cardiovascular risk factors like lipid profiles, and some have even noted a decrease in beneficial HDL cholesterol.

- Growth Hormone Peptides (Sermorelin/Ipamorelin) ∞ These are not hormones themselves but are secretagogues, meaning they stimulate the pituitary gland to release more of the body’s own growth hormone (GH). GH has known benefits for body composition, such as increasing muscle mass and reducing fat, which can indirectly support cardiovascular health. Peptides like Sermorelin act as an analog of growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH). While they are popular for anti-aging and wellness, their direct, long-term cardiovascular benefits and risks are less studied than traditional hormone therapies. Some users report side effects like increased heart rate, indicating a direct effect on the cardiovascular system that requires careful consideration.

The following table provides a comparative overview of these primary hormonal interventions and their documented effects on key aspects of cardiovascular health.

| Intervention | Primary Mechanism | Effect on Blood Vessels | Effect on Body Composition | Key Clinical Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Dose Testosterone | Directly replaces low testosterone levels. | Promotes vasodilation via nitric oxide production. | Increases lean muscle mass, reduces fat mass. | Recent large trials support its cardiovascular safety in hypogonadal men. |

| Estrogen Therapy | Directly replaces low estrogen levels. | Supports endothelial health, may have antioxidant effects. | Generally neutral or minor effects. | Effects are highly dependent on timing of initiation relative to menopause (Timing Hypothesis). |

| DHEA | Acts as a precursor to testosterone and estrogen. | May improve endothelial function and promote vasodilation. | Effects are inconsistent in clinical studies. | Mixed results in trials; may lower HDL cholesterol. |

| GH Peptides (Sermorelin, etc.) | Stimulate pituitary to release more growth hormone. | Indirect effects via GH; potential for increased heart rate. | Increases lean muscle mass, reduces fat mass. | Limited long-term cardiovascular safety data. |

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of hormonal interventions on cardiovascular health Meaning ∞ Cardiovascular health denotes the optimal functional state of the heart and the entire vascular network, ensuring efficient circulation of blood, oxygen, and nutrients throughout the body. moves beyond cataloging outcomes and into the realm of molecular mechanisms and systems biology. The central arena where these therapies exert their influence is the vascular endothelium, a highly active, single-cell-thick lining of all blood vessels.

Its health dictates vascular tone, inflammation, and the progression of atherosclerosis. Therefore, a comparison of low-dose testosterone, estrogen, and other hormonal agents can be framed through their differential effects on endothelial function Meaning ∞ Endothelial function refers to the physiological performance of the endothelium, the thin cellular layer lining blood vessels. and vascular inflammatory processes.

Endothelial Function as the Common Pathway

The endothelium is the gatekeeper of vascular health. A healthy endothelium produces nitric oxide Meaning ∞ Nitric Oxide, often abbreviated as NO, is a short-lived gaseous signaling molecule produced naturally within the human body. (NO), a powerful signaling molecule that promotes vasodilation, inhibits platelet aggregation, and suppresses inflammation. Endothelial dysfunction, characterized by reduced NO bioavailability, is a foundational step in the development of cardiovascular disease.

Testosterone’s role here is multifaceted. It can exert its effects through both genomic and non-genomic pathways. The genomic pathway involves the binding of testosterone to androgen receptors within endothelial cells, which then translocate to the nucleus to regulate gene expression, including the upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), the enzyme responsible for producing NO.

The non-genomic pathway is more rapid and involves testosterone interacting with membrane-bound receptors to quickly modulate intracellular signaling cascades, also leading to eNOS activation. Low testosterone Meaning ∞ Low Testosterone, clinically termed hypogonadism, signifies insufficient production of testosterone. levels are associated with impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation, a condition that testosterone therapy has been shown to improve in some studies.

Estrogen, primarily estradiol (E2), is also a potent modulator of endothelial function. Like testosterone, it upregulates eNOS expression and activity. It also possesses antioxidant properties, protecting the endothelium from oxidative stress, and favorably modulates the lipid profile by lowering LDL and increasing HDL cholesterol.

The WHI trial’s confounding results may be partly explained by the specific formulation used (CEE contains a mix of estrogens, some with different effects than estradiol) and the oral route of administration, which can lead to a first-pass effect in the liver that increases the production of clotting factors and inflammatory proteins like C-reactive protein. This illustrates how the delivery method and molecular form of a hormone are as critical as the hormone itself.

The vascular endothelium represents the primary site where distinct hormonal therapies exert their convergent and divergent effects on cardiovascular health.

How Do These Interventions Compare at the Molecular Level?

When we scrutinize the data from clinical trials through this mechanistic lens, a more granular picture forms. The choice between hormonal interventions depends on the specific physiological imbalances and the desired therapeutic targets.

- Impact on Atherosclerotic Plaque ∞ This is a critical endpoint. The Testosterone Trials (TTrials) found that one year of testosterone therapy in older men with low testosterone was associated with a greater increase in non-calcified coronary artery plaque volume compared to placebo, although there was no difference in calcified plaque. Non-calcified plaque is generally considered less stable and more prone to rupture. This finding introduces a layer of complexity to the overall safety profile suggested by the TRAVERSE trial, which focused on major adverse cardiac events. In contrast, the effects of estrogen are timing-dependent. In newly menopausal women, estrogen may slow the progression of atherosclerosis, whereas in older women with established plaque, it may promote inflammation within that plaque.

- Influence on Inflammation and Coagulation ∞ Testosterone generally exhibits anti-inflammatory properties, with some studies showing it can lower levels of inflammatory cytokines like TNF-alpha and IL-1beta. Oral estrogen, as seen in the WHI, can increase C-reactive protein and the risk of venous thromboembolism. Transdermal estrogen appears to bypass this liver-mediated inflammatory response, making it a potentially safer option from a cardiovascular standpoint. DHEA’s effects on inflammation are less clear, with some studies suggesting anti-inflammatory actions while others show no significant impact.

- Metabolic Parameters ∞ This is an area where testosterone therapy shows consistent benefits. By improving insulin sensitivity and promoting lean mass, it directly counteracts the metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions that dramatically increases cardiovascular risk. The cardiometabolic benefits of testosterone were also highlighted in the T4DM trial. Estrogen’s effects on insulin sensitivity are more variable. DHEA supplementation has shown some promise in improving insulin sensitivity in certain populations, but the evidence is not robust. Growth hormone peptides like Sermorelin can also improve insulin sensitivity, but their long-term impact on glucose metabolism requires further study.

The following table provides a detailed, academic comparison of these hormonal interventions based on specific cardiovascular and metabolic endpoints from clinical research.

| Biomarker/Endpoint | Low-Dose Testosterone | Estrogen Therapy (Post-Menopause) | DHEA | GH Peptides (Sermorelin, etc.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endothelial Function (NO Bioavailability) | Generally improves; upregulates eNOS. | Improves, especially when initiated early; upregulates eNOS. | May improve; data is less consistent. | Indirect effects; not well-studied for this endpoint. |

| Arterial Plaque Composition | May increase non-calcified plaque volume. | Effect is timing-dependent; may slow early progression. | Limited data; some evidence for anti-atherosclerotic effects. | Limited human data on direct plaque effects. |

| C-Reactive Protein (CRP) | Tends to decrease or remain neutral. | Oral formulations may increase CRP; transdermal is neutral. | Inconsistent effects. | Limited data. |

| Lipid Profile | May slightly decrease HDL; reduces total cholesterol. | Lowers LDL, raises HDL (oral). | May decrease HDL; other effects are minimal. | Generally improves by reducing body fat. |

| Insulin Sensitivity | Consistently improves. | Variable effects depending on formulation. | May improve in some populations. | May improve. |

| Thrombotic Risk | May increase hematocrit; overall risk increase is debated. | Oral formulations increase risk of VTE. | No clear evidence of increased risk. | No clear evidence of increased risk. |

References

- Manson, JoAnn E. et al. “Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials.” JAMA, vol. 310, no. 13, 2013, pp. 1353-68.

- Vigen, Rebecca, et al. “Association of testosterone therapy with mortality, myocardial infarction, and stroke in men with low testosterone levels.” JAMA, vol. 310, no. 17, 2013, pp. 1829-36.

- Basaria, Shehzad, et al. “Adverse events associated with testosterone administration.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 363, no. 2, 2010, pp. 109-22.

- Lincoff, A. Michael, et al. “Cardiovascular Safety of Testosterone-Replacement Therapy.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 389, no. 2, 2023, pp. 107-117.

- Jones, T. Hugh, et al. “Testosterone and the metabolic syndrome.” The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology, vol. 145, 2015, pp. 156-65.

- Samaras, N. et al. “Dehydroepiandrosterone and its sulfate, sex hormones, and related analyzes, in the general population and in cardiovascular diseases. A review of the literature.” Hormones (Athens), vol. 12, no. 4, 2013, pp. 484-94.

- Corpas, E. S. M. Harman, and M. R. Blackman. “Human growth hormone and human aging.” Endocrine reviews, vol. 14, no. 1, 1993, pp. 20-39.

- Baillargeon, Jacques, et al. “Risk of myocardial infarction in older men receiving testosterone therapy.” The Annals of Pharmacotherapy, vol. 47, no. 9, 2013, pp. 1138-44.

- Rossouw, Jacques E. et al. “Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women ∞ principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial.” JAMA, vol. 288, no. 3, 2002, pp. 321-33.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a map of the current clinical landscape, detailing the intricate ways hormonal signals influence the cardiovascular system. This knowledge is a powerful tool, shifting the perspective from one of passive symptom management to one of proactive, informed self-stewardship. The data reveals that there is no single, universal answer. The optimal path is one that is highly personalized, taking into account your unique biology, genetics, and life stage.

Your own health journey is a unique narrative. The biological mechanisms discussed are the language in which that story is written. Understanding this language allows you to ask more precise questions and to engage with healthcare professionals as a partner in your own wellness.

The ultimate goal is to align your internal physiology with your desire for a long, vital, and functional life. This exploration is the starting point for a deeper conversation about what that alignment looks like for you.