Fundamentals

You feel it before you can name it. A persistent fatigue that sleep does not touch, a subtle shift in your mood, or the sense that your body is no longer responding with the vitality it once possessed. These experiences are valid and deeply personal.

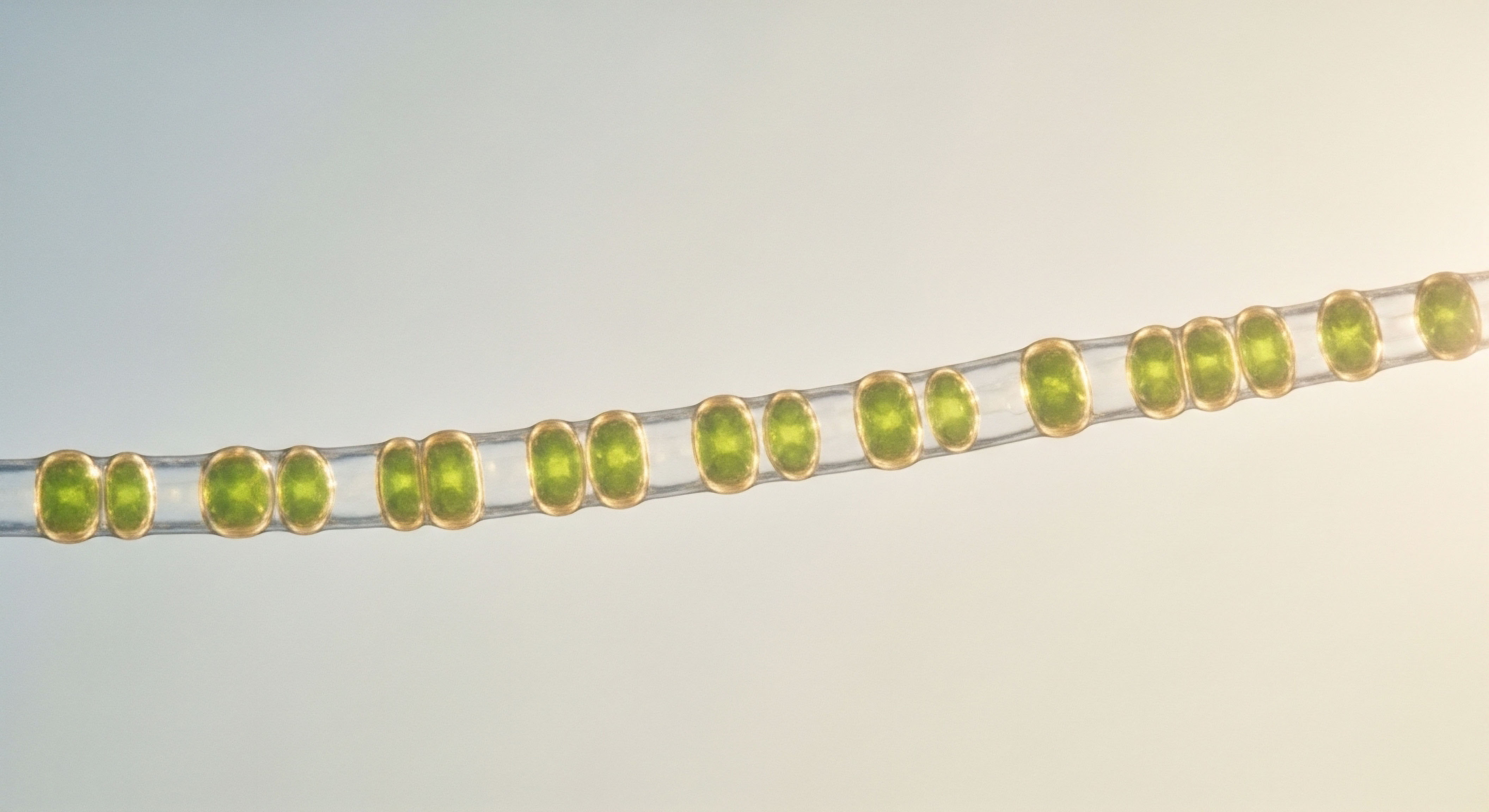

They are the body’s way of communicating a change in its internal environment. This communication system, a vast and elegant network of hormonal messages, governs everything from our energy levels to our cognitive clarity. At the very center of this network, acting as the master regulator and metabolic clearinghouse, is the liver. Your journey to understanding your hormonal health begins with appreciating the profound role this single organ plays in orchestrating these biochemical conversations.

When you begin a hormonal optimization protocol, such as testosterone replacement for men or estrogen and progesterone support for women, you are introducing a powerful new voice into this conversation. The effectiveness of this intervention depends almost entirely on how the liver receives, processes, and distributes these new hormonal signals.

Every substance that enters your bloodstream is assessed by the liver. For orally administered hormones, this initial encounter is known as the “first-pass effect.” The hormone is absorbed from the digestive tract and travels directly to the liver, which metabolizes a significant portion before it ever reaches the rest of the body. This initial processing step dictates the ultimate dose and impact of the therapy.

The liver acts as the central command for processing and distributing both naturally produced and therapeutic hormones, directly shaping their effect on the body.

The Liver as a Metabolic Filter

Think of the liver as an incredibly sophisticated quality control and distribution center. It receives raw materials, in this case, hormones, and modifies them for use or for elimination. This metabolic function ensures that hormonal signals are delivered at the right intensity and for the right duration.

When liver function is robust, this process is seamless. Hormones are converted into their active forms, used by the body’s tissues, and then deactivated and safely excreted. A healthy liver ensures a clean, clear signal.

When its capacity is diminished, however, this intricate system can falter. The deactivation process may slow, leading to a buildup of hormonal byproducts. The activation of therapeutic hormones might become inefficient, requiring adjustments in dosing. Understanding this fundamental relationship is the first step toward a successful and safe hormonal recalibration.

Your symptoms are real, and they are pointing toward a systemic imbalance. By focusing on the health of the organ responsible for maintaining that balance, you are addressing the root of the issue, preparing your body to respond optimally to therapeutic support.

What Is First Pass Metabolism?

First-pass metabolism is a biological process that significantly influences how oral medications and hormones are handled by the body. After a substance is swallowed and absorbed through the gastrointestinal tract, the portal vein transports it directly to the liver.

Here, a large portion of the active compound can be metabolized and inactivated by liver enzymes before it ever enters the systemic circulation to reach its target tissues. This effect is why some therapies are administered through other routes, such as transdermal patches, subcutaneous injections, or pellets.

These methods bypass the liver on the first pass, allowing for a more direct and predictable delivery of the hormone into the bloodstream. The choice of delivery method for hormone replacement therapy is therefore a strategic decision based on its interaction with the liver.

Intermediate

Advancing our understanding of hormonal optimization requires a more detailed look at the specific biochemical machinery within the liver. This organ’s influence extends far beyond simple filtration. It actively synthesizes key proteins and utilizes specific enzyme systems that dictate the bioavailability, activity, and clearance of sex hormones. The success of any hormonal protocol, from weekly Testosterone Cypionate injections for men to low-dose testosterone with progesterone for women, is directly modulated by the efficiency of these hepatic systems.

The Liver’s Metabolic Machinery Cytochrome P450 Enzymes

The primary system the liver uses to metabolize hormones is a superfamily of enzymes known as Cytochrome P450 (CYP450). These are the workhorses of drug and hormone metabolism. For androgens and estrogens, the CYP3A4 enzyme is particularly significant.

It hydroxylates these steroid hormones, which is a chemical step that renders them more water-soluble and prepares them for excretion from the body. The activity level of your CYP450 enzymes can be influenced by genetics, lifestyle, and the presence of other medications. If this system is sluggish, hormones may linger in the body longer than intended, potentially increasing the risk of side effects. Conversely, an overactive system might clear hormones too quickly, reducing the effectiveness of a standard dose.

Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin the Gatekeeper of Bioavailability

The liver manufactures a protein called Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG), which acts as the primary transport vehicle for testosterone and estradiol in the bloodstream. SHBG binds tightly to these hormones, rendering them biologically inactive while in transit. Only the “free” or unbound portion of a hormone can enter a cell and activate its receptor.

Therefore, the amount of SHBG produced by the liver directly regulates your level of active, usable hormones. High SHBG levels mean less free hormone is available, potentially masking the benefits of therapy. Low SHBG levels result in more free hormone, which can enhance therapeutic effects but also increase the potential for androgenic or estrogenic side effects. Liver health is a primary determinant of SHBG production; conditions like insulin resistance and fatty liver disease are known to suppress SHBG levels.

The liver’s production of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) directly controls the amount of active, free hormones available to your body’s tissues.

This is why assessing SHBG is a standard part of interpreting lab results for hormonal health. It provides critical context to the total testosterone or estrogen reading. For instance, a man on TRT might have a robust total testosterone level, but if his SHBG is excessively high, he may still experience symptoms of low T because his free testosterone is inadequate.

Protocols can be adjusted to account for this, sometimes by modifying the dose or frequency of administration, or by addressing the underlying liver issue that may be elevating SHBG.

How Does Delivery Method Impact the Liver?

The route of administration for hormone therapy is chosen specifically to manage the liver’s influence. Oral estrogens, for example, have a strong first-pass effect that significantly increases the liver’s production of SHBG and other proteins. This can alter the therapy’s overall effect.

In contrast, transdermal (patch or gel) and injectable routes, like the Testosterone Cypionate used in male and female protocols, bypass this first-pass metabolism. This results in more predictable blood levels and less impact on liver protein synthesis. The choice between oral, transdermal, or injectable methods is a clinical decision made to best suit the individual’s metabolic profile and therapeutic goals.

| Delivery Route | First-Pass Metabolism | Impact on SHBG Production | Typical Protocols |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral |

High. The hormone is processed extensively by the liver before entering systemic circulation. |

Significant increase. Oral estrogens are known to elevate SHBG levels substantially. |

Some forms of estrogen and progesterone therapy. |

| Transdermal (Patch/Gel) |

Avoided. The hormone is absorbed through the skin directly into the bloodstream. |

Minimal. This route does not directly stimulate hepatic protein synthesis in the same way. |

Estradiol patches, testosterone gels. |

| Injectable (IM/SubQ) |

Avoided. The hormone is injected into muscle or subcutaneous fat and absorbed over time. |

Minimal. Provides a depot of hormone that is released steadily into circulation. |

Testosterone Cypionate, Testosterone Enanthate. |

| Pellet Implant |

Avoided. Pellets are inserted subcutaneously and release the hormone slowly over months. |

Minimal. Offers a very stable, long-term release without hepatic first-pass. |

Testosterone pellets. |

- Anastrozole Use ∞ In protocols for both men and women, particularly with testosterone administration, an agent like Anastrozole may be used. This oral medication blocks the aromatase enzyme, which converts testosterone to estrogen. Its metabolism is also handled by the liver, highlighting the organ’s central role in managing not just the primary hormones but the ancillary medications as well.

- Gonadorelin and Fertility ∞ For men on TRT, Gonadorelin is often prescribed to maintain testicular function. As a peptide, its clearance pathways are different from steroid hormones, yet the overall metabolic health supported by the liver contributes to the body’s ability to process all therapeutic agents effectively.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of hormone replacement therapy outcomes necessitates a deep examination of the patient’s underlying metabolic state, which is often mirrored in the health of the liver. The rising prevalence of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), previously known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), presents a significant variable in clinical practice.

MASLD is the hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome and its presence fundamentally alters the liver’s capacity to manage steroid hormones, thereby influencing the safety and efficacy of hormonal optimization protocols.

The Pathophysiology of MASLD and Hormonal Dysregulation

MASLD is characterized by the accumulation of triglycerides within hepatocytes, a condition driven by insulin resistance and systemic inflammation. This is not a passive state of fat storage. It is an active, metabolically disruptive condition that degrades the liver’s core functions.

In the context of hormone therapy, MASLD interferes with two critical pathways ∞ the synthesis of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) and the function of cytochrome P450 enzymes. Research consistently shows a strong inverse relationship between MASLD and serum SHBG levels.

The hepatic insulin resistance characteristic of MASLD suppresses the genetic transcription of the SHBG gene, leading to lower circulating levels of this binding protein. This results in a higher fraction of free testosterone and estradiol, which can paradoxically exacerbate symptoms or side effects even with therapeutic doses of HRT.

The inflammatory state and insulin resistance of metabolic liver disease actively suppress the production of key hormone-regulating proteins, disrupting the intended balance of therapy.

How Does MASLD Alter Therapeutic Outcomes?

The presence of MASLD can create a challenging clinical picture. For a man on a standard TRT protocol (e.g. 200mg/ml Testosterone Cypionate weekly), the suppressed SHBG can lead to supraphysiologic levels of free testosterone shortly after injection. This may increase the rate of aromatization to estradiol and necessitate more aggressive management with an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole.

For a postmenopausal woman, the combination of exogenous hormones and low SHBG can lead to a hormonal profile that promotes further metabolic disruption. The route of administration becomes a critical consideration. Transdermal or injectable therapies that avoid the first-pass effect are generally preferred in individuals with MASLD to prevent further stressing the liver’s metabolic capacity.

Studies have indicated that oral MHT might be associated with an increased risk for the development and progression of NAFLD, whereas transdermal routes may be protective.

The inflammatory milieu of MASLD, characterized by elevated cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6, can also induce a state of hormone receptor resistance. Even with adequate free hormone levels, the cellular signaling process may be blunted, leading to a disconnect between lab values and the patient’s subjective experience. The therapeutic goal then expands from simply replacing hormones to improving the metabolic environment in which those hormones must function.

| Parameter | State in Healthy Liver | State in MASLD Liver | Clinical Implication for HRT |

|---|---|---|---|

| SHBG Production |

Normal, regulated production maintains balance of free and bound hormones. |

Suppressed due to hepatic insulin resistance, leading to low serum SHBG. |

Higher free hormone fractions; potential for increased side effects and need for dose adjustment. |

| CYP450 Function |

Efficient metabolism and clearance of hormones and their byproducts. |

Function can be impaired, altering the clearance rate of steroid hormones. |

Unpredictable hormone half-life, potentially requiring changes in dosing frequency. |

| Inflammatory State |

Low systemic inflammation. |

Pro-inflammatory state with elevated cytokines. |

Potential for hormone receptor resistance, reducing therapeutic effectiveness. |

| Glucose Homeostasis |

Maintains stable blood glucose. |

Marked by insulin resistance and impaired glucose output regulation. |

Hormonal shifts can further impact glycemic control, a key consideration in therapy. |

- Metabolic Disruption Begins ∞ Insulin resistance develops, leading to increased fat storage in the liver.

- SHBG Synthesis Declines ∞ The liver reduces its production of SHBG, a direct consequence of the metabolic stress.

- Free Hormone Levels Rise ∞ With less SHBG to bind to, the percentage of free, active testosterone and estrogen increases in circulation.

- Hormone Clearance is Altered ∞ The efficiency of CYP450 enzymes may be compromised by cellular stress and inflammation, affecting how quickly hormones are broken down.

- Systemic Inflammation Worsens ∞ The unhealthy liver releases inflammatory signals that can interfere with hormone receptors throughout the body, making tissues less responsive to hormonal signals.

This deep biological interplay underscores the necessity of a systems-based approach. Optimizing hormonal therapy in the presence of liver compromise requires addressing the metabolic health of the liver itself as a primary therapeutic target. Strategies to improve insulin sensitivity and reduce hepatic steatosis are not merely adjacent to HRT; they are integral to its success.

References

- Szymczak-Gajewska, Iga, et al. “Sex hormone binding globulin as a potential drug candidate for liver-related metabolic disorders treatment.” Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, vol. 153, 2022, p. 113261.

- Jaruvongvanich, V. et al. “Testosterone, Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease ∞ A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Annals of Hepatology, vol. 16, no. 3, 2017, pp. 382-394.

- Vryonidou, A. et al. “Menopause and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease ∞ A Review Focusing on Therapeutic Perspectives.” Current Medicinal Chemistry, vol. 25, no. 1, 2018.

- Lee, H. R. et al. “Different effects of menopausal hormone therapy on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease based on the route of estrogen administration.” Scientific Reports, vol. 11, no. 1, 2021, p. 20197.

- Mauvais-Jarvis, Franck, et al. “Metabolic benefits afforded by estradiol and testosterone in both sexes ∞ clinical considerations.” The Journal of Clinical Investigation, vol. 134, no. 17, 2024, p. e180073.

- Pfizer Inc. “Testosterone Cypionate Injection, USP CIII – Label.” 2018.

- Waxman, D. J. and C. Holloway, M.G. “Steroid regulation of drug-metabolizing cytochromes P450.” Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, vol. 300, no. 1-2, 2009, pp. 75-84.

- Long, C. A. and J. L. Crocker. “The Influence of Sex Hormones in Liver Function and Disease.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 23, no. 23, 2022, p. 15291.

- Wu, T. et al. “Associations of Sex Steroids and Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease ∞ A Population-Based Study and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Clinical Medicine, vol. 11, no. 11, 2022, p. 3086.

- Kharoud, M. et al. “Population Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Modeling of Depot Testosterone Cypionate in Healthy Male Subjects.” Clinical and Translational Science, vol. 12, no. 5, 2019, pp. 527-536.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a map of the biological territory connecting your liver to your hormonal vitality. It details the machinery, the pathways, and the potential points of disruption. This knowledge is a powerful tool, shifting the perspective from one of managing isolated symptoms to one of cultivating a resilient, integrated system.

Your body’s hormonal state is a direct reflection of its overall metabolic health, and the liver stands at the crossroads of this relationship. Consider your own health journey. What aspects of your lifestyle support the metabolic work your liver must perform every day?

Viewing your path to wellness through this lens transforms it into a proactive partnership with your own biology. The goal becomes creating an internal environment where therapeutic interventions can work in concert with your body’s inherent capacity for balance and function.