Fundamentals

Living with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) often involves a frustrating and deeply personal series of physical and emotional experiences. You may feel as though your body is operating under a set of rules you were never taught, leading to irregular menstrual cycles, metabolic challenges, and changes in your physical appearance that can affect your sense of self.

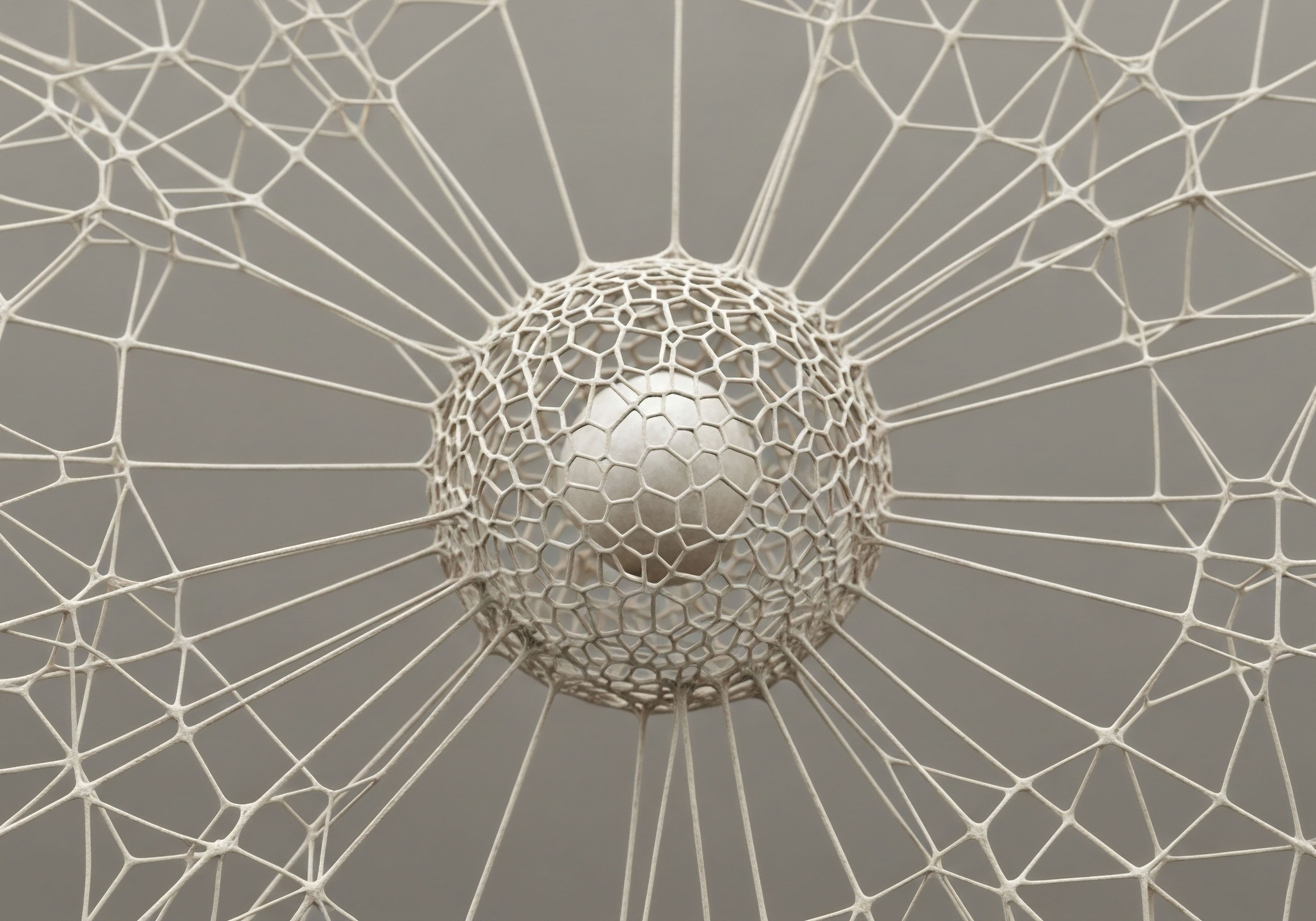

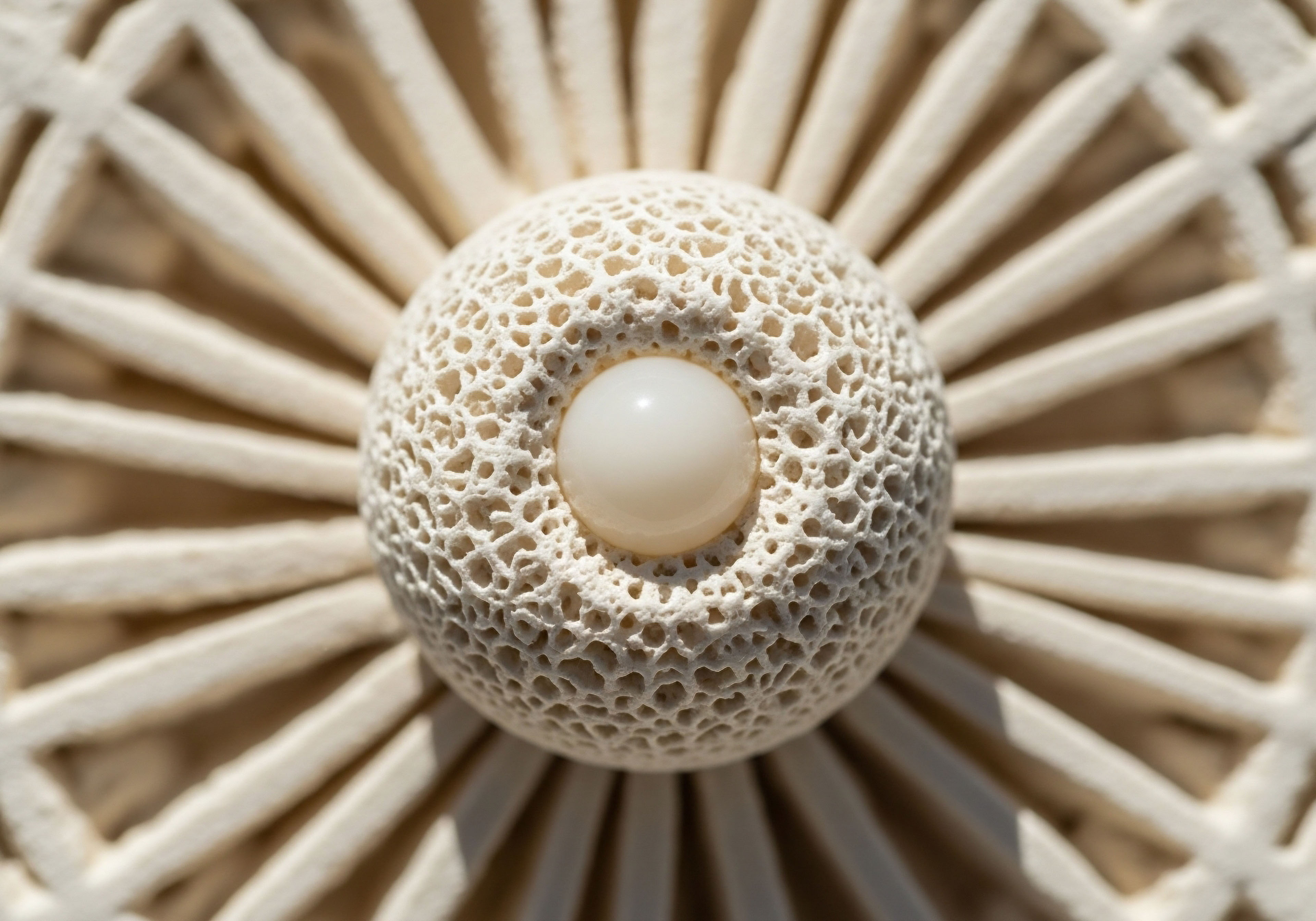

Understanding the root of these symptoms is the first step toward reclaiming a sense of control and partnership with your own biology. At the center of this complex condition lies a profound disruption in the body’s internal communication systems, particularly the way your cells listen to and respond to the hormone insulin. This is where the story of inositol begins, not as a simple supplement, but as a key that can help restore a vital conversation within your body.

Imagine insulin as a messenger, dispatched after a meal to knock on the doors of your cells and instruct them to take in glucose for energy. In many women with PCOS, the “locks” on these cellular doors have become resistant. The cells do not hear the knock as clearly as they should.

In response, the body’s control center, the pancreas, sends out more and more insulin, raising its volume in an attempt to be heard. This state of high insulin, known as hyperinsulinemia, creates a cascade of downstream effects. One of the most significant of these effects occurs within the ovaries.

The ovaries, sensitive to this high-volume insulin signal, are stimulated to produce an excess of androgens, or male hormones. This hormonal imbalance is a primary driver of many hallmark PCOS symptoms, including disruptions to ovulation, acne, and hirsutism. The entire system is caught in a feedback loop where metabolic dysfunction fuels hormonal imbalance, which in turn can worsen the metabolic state.

The Cellular Signal Restorer

Inositol enters this picture as a critical component of the cell’s listening apparatus. It is a type of sugar alcohol, a member of the vitamin B complex family, that your body produces and also obtains from certain foods.

Its primary role in this context is to function as a “second messenger.” When the insulin messenger arrives at the cell’s door, it is inositol-containing molecules inside the cell that swing the door open, allowing glucose to enter. Without sufficient or correctly balanced inositols, the cell’s ability to respond to insulin is impaired.

This creates the very insulin resistance that initiates the hormonal cascade in PCOS. By providing the body with specific forms of inositol, we are essentially helping to repair the locks on the cell doors. This allows the cells to hear the insulin signal at a normal volume once again.

Consequently, the pancreas no longer needs to shout; insulin levels can normalize, and the overstimulation of the ovaries begins to subside. This biochemical recalibration gets to the heart of the issue, addressing the metabolic root cause to alleviate the hormonal symptoms.

Inositol acts as a secondary messenger within cells, helping to amplify insulin’s signal and thereby improving the body’s glucose processing and reducing the hormonal imbalances characteristic of PCOS.

Re-Establishing Ovarian Rhythm

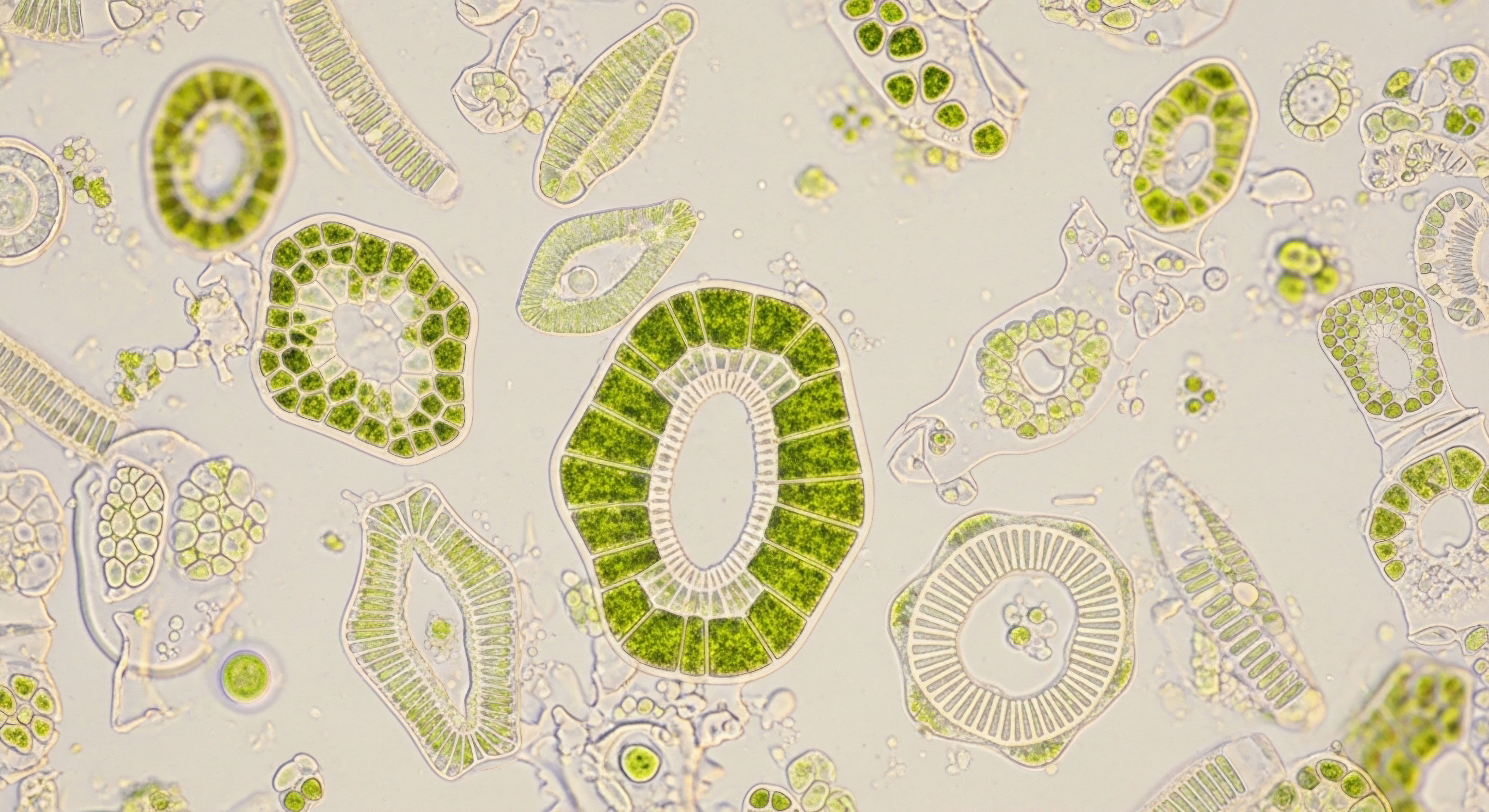

The influence of inositol extends directly to ovarian function itself. Beyond its role in insulin signaling, specific types of inositol are fundamentally involved in the signaling pathways of Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). FSH is the hormone responsible for signaling the ovaries to mature a follicle each month in preparation for ovulation.

In PCOS, this signaling process is often disrupted. The follicles may begin to develop but then stall, leading to the characteristic “polycystic” appearance of the ovaries on an ultrasound and, more importantly, to anovulation, or the absence of ovulation. This results in the irregular or absent menstrual cycles that are a defining feature of the condition.

Myo-inositol, a specific stereoisomer of inositol, is particularly crucial for healthy FSH signaling. When ovarian cells have adequate levels of myo-inositol, they become more sensitive and responsive to FSH. This improved sensitivity helps the follicles to mature properly, culminating in successful ovulation.

By supporting both insulin and FSH signaling, inositol helps to restore the natural, rhythmic communication between the brain and the ovaries. This process re-establishes a more predictable ovulatory cycle, which is a foundational element of reproductive health and overall endocrine balance. The journey toward managing PCOS is one of restoring balance to these intricate biological systems, and understanding inositol’s role provides a powerful tool for that restoration.

Intermediate

For those already familiar with the basics of PCOS and insulin resistance, a deeper examination reveals a more detailed picture of inositol’s function. The term “inositol” refers to a family of nine distinct stereoisomers, but two, in particular, are central to ovarian health in PCOS ∞ myo-inositol (MI) and D-chiro-inositol (DCI).

These two molecules, while structurally similar, perform different and specific roles within the body’s tissues. Their balance is critical, and a disruption in this balance is now understood to be a core pathophysiological feature of PCOS at the ovarian level. Understanding their distinct functions and their necessary synergy is key to appreciating the clinical protocols designed to manage the condition effectively.

In a healthy individual, most tissues maintain a specific ratio of MI to DCI, typically around 40 to 1. MI is the most abundant form and serves as the precursor to DCI. The conversion of MI to DCI is carried out by an enzyme called epimerase, and this conversion is insulin-dependent.

When insulin levels rise, epimerase activity increases, producing more DCI. In peripheral tissues like muscle and fat, DCI is vital for insulin-mediated glucose storage. MI, on the other hand, is primarily responsible for glucose uptake and serves as the second messenger for hormones like FSH and TSH. In a state of systemic insulin resistance, the body’s peripheral tissues become deficient in DCI, contributing to high blood sugar. Paradoxically, the ovary in a woman with PCOS behaves quite differently.

What Is the Ovarian Paradox?

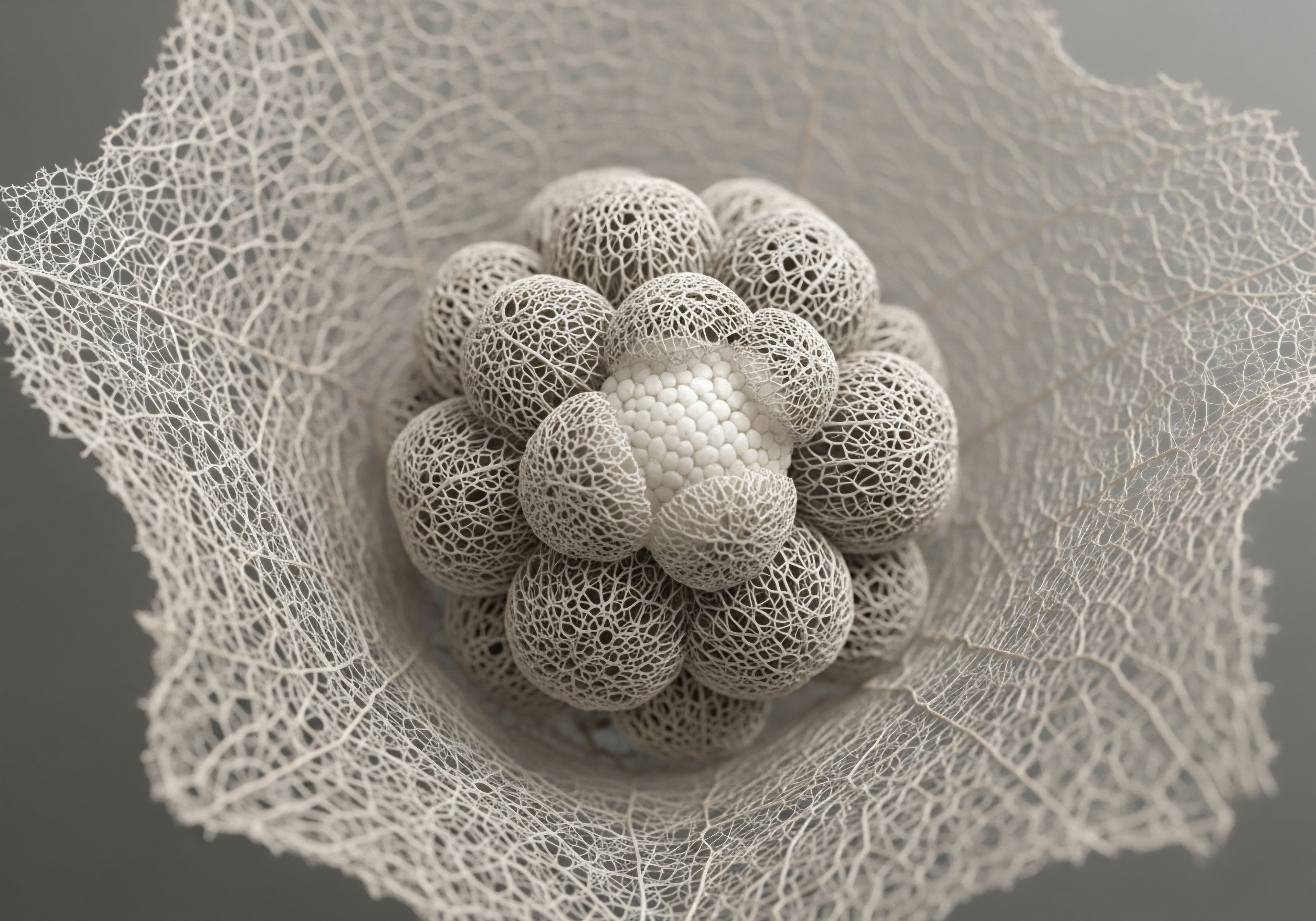

The concept of the “ovarian paradox” is central to understanding why inositol supplementation is so specific in PCOS. While the rest of the body’s tissues may be insulin-resistant, the ovarian theca cells remain exquisitely sensitive to insulin. In the presence of the high insulin levels common in PCOS, the epimerase enzyme within the ovary goes into overdrive.

This leads to an accelerated conversion of MI to DCI directly within the ovary. The result is a local environment within the follicular fluid that is depleted of MI and has an overabundance of DCI. This localized imbalance has two profound consequences.

First, the depletion of MI impairs the ovary’s ability to respond to FSH, disrupting follicular development and contributing to poor oocyte quality. Second, the excess of DCI promotes insulin-mediated androgen synthesis by the theca cells, directly fueling the hyperandrogenism (high testosterone) that drives many PCOS symptoms. Therefore, the very mechanism that the body uses to compensate for insulin resistance systemically creates a detrimental hormonal environment within the ovary. Simply supplementing with DCI alone can worsen this ovarian imbalance.

Restoring Balance with a Physiological Ratio

Clinical protocols have evolved to address this paradox directly. Research has demonstrated that supplementing with a combination of MI and DCI in the physiological plasma ratio of 40:1 is the most effective approach for restoring ovulatory function in women with PCOS. This specific formulation is designed to achieve two goals simultaneously.

The high dose of MI works to replenish the depleted stores within the ovary, thereby improving FSH signaling, supporting follicle maturation, and enhancing oocyte quality. Concurrently, the small, physiological dose of DCI helps to address the systemic insulin resistance without overwhelming the ovary and exacerbating androgen production. This dual-action approach respects the distinct roles of each isomer and aims to normalize the MI/DCI ratio both systemically and, most importantly, within the intrafollicular environment.

Clinical evidence indicates that a 40:1 ratio of myo-inositol to D-chiro-inositol is the optimal combination for restoring ovulation by simultaneously addressing follicular development and systemic insulin sensitivity.

The table below outlines the distinct and complementary functions of Myo-Inositol and D-Chiro-Inositol, illustrating why a combined approach is often necessary for comprehensive PCOS management.

| Feature | Myo-Inositol (MI) | D-Chiro-Inositol (DCI) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Ovarian Role | Mediates Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) signaling, crucial for oocyte maturation and follicular development. | Mediates insulin-dependent androgen synthesis in theca cells. |

| Systemic Metabolic Role | Facilitates cellular glucose uptake. | Promotes glycogen synthesis and storage. |

| Level in PCOS Ovary | Depleted due to accelerated conversion to DCI. | Excessively high due to hyperinsulinemia-driven epimerase activity. |

| Effect of Supplementation | Restores FSH sensitivity, improves oocyte and embryo quality, and can help regulate menstrual cycles. | Improves systemic insulin sensitivity but can worsen hyperandrogenism if given in high doses alone. |

This targeted biochemical recalibration has been shown in clinical trials to produce significant improvements in both metabolic and reproductive parameters for women with PCOS. The goal is a restoration of the body’s own finely tuned system.

Clinical Outcomes and Protocols

The application of combined inositol therapy is supported by a growing body of clinical evidence. Studies evaluating the 40:1 MI/DCI ratio have documented a range of positive outcomes. These are not just theoretical benefits; they are measurable changes in biomarkers and patient-reported experiences.

- Restoration of Ovulation ∞ Many studies report a significant increase in ovulation frequency and menstrual regularity in women treated with the 40:1 ratio compared to placebo or other ratios.

- Improved Hormonal Profile ∞ Treatment has been associated with a reduction in circulating levels of LH, total and free testosterone, and an increase in Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG), which binds to and inactivates excess androgens.

- Enhanced Metabolic Markers ∞ Patients often show improvements in insulin sensitivity, with reductions in fasting insulin levels and the HOMA-IR index, a measure of insulin resistance.

- Better Oocyte Quality ∞ In the context of assisted reproductive technologies, MI supplementation has been linked to a higher number of mature oocytes retrieved and better embryo quality, likely due to its role in FSH signaling and oocyte development.

A typical clinical protocol involves a daily dose of 4 grams of Myo-Inositol and 100 milligrams of D-Chiro-Inositol, reflecting the 40:1 ratio. This is usually taken in two divided doses. It is considered a safe intervention with minimal side effects, which are typically mild gastrointestinal complaints. This evidence-based approach provides a sophisticated therapeutic tool that moves beyond managing symptoms to address the underlying biochemical imbalances of PCOS.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of inositol’s role in polycystic ovary syndrome requires a departure from simplified analogies and an entry into the precise language of molecular endocrinology. The pathophysiology of PCOS is rooted in a complex interplay between the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis and metabolic dysregulation, specifically post-receptor defects in insulin signaling.

The therapeutic action of inositol isomers is best understood by examining their function as precursors to inositolphosphoglycan (IPG) second messengers and the tissue-specific dysregulation of the epimerase enzyme that governs their interconversion. This granular perspective clarifies how systemic hyperinsulinemia translates into the specific ovarian phenotype of hyperandrogenism and anovulation.

The foundational mechanism resides in the phosphatidylinositol (PI) signaling pathway. Upon binding to its receptor, insulin activates a cascade that leads to the hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), a membrane phospholipid. This hydrolysis, catalyzed by phospholipase C (PLC), generates two key second messengers ∞ inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG).

IP3 mobilizes intracellular calcium, a critical step for numerous cellular processes, while DAG activates protein kinase C (PKC). IPGs containing myo-inositol (MI-IPG) and D-chiro-inositol (DCI-IPG) function as mediators of distinct downstream insulin actions.

MI-IPG primarily mediates insulin’s effects on glucose transport via GLUT4 translocation, while DCI-IPG is more involved in the activation of glycogen synthase and pyruvate dehydrogenase, key enzymes in glucose storage and oxidation. A deficiency or imbalance in these mediators contributes directly to the state of insulin resistance.

How Does Epimerase Dysregulation Drive Ovarian Pathology?

The critical enzyme in this pathway is the NAD/NADH-dependent epimerase, which catalyzes the conversion of MI to DCI. The activity of this enzyme is directly stimulated by insulin. In a healthy state, this allows tissues to generate the appropriate amount of DCI needed to manage glucose disposal.

In women with PCOS, chronic compensatory hyperinsulinemia creates a state of profound epimerase dysregulation that differs by tissue type. In peripheral tissues like muscle and liver, there appears to be impaired epimerase activity, leading to a DCI deficiency that exacerbates systemic insulin resistance. The ovary, however, presents a paradoxical situation.

The ovarian theca cells do not develop insulin resistance and, in fact, may exhibit insulin hypersensitivity. Consequently, the high circulating insulin levels cause a dramatic upregulation of epimerase activity within the ovary. This leads to a rapid and excessive conversion of local MI stores into DCI.

The resulting high intra-ovarian DCI/MI ratio is pathognomonic for the PCOS ovary and is the direct molecular link between hyperinsulinemia and ovarian dysfunction. The excess DCI stimulates the P450c17 enzyme, enhancing androgen biosynthesis, while the concomitant depletion of MI impairs FSH receptor signaling, leading to arrested follicular development and diminished oocyte quality.

Quantitative Impact on Hormonal and Ovulatory Parameters

Clinical trials provide quantitative data validating this molecular model. The administration of inositol, particularly in the physiological 40:1 MI/DCI ratio, aims to correct this specific ovarian defect. The table below synthesizes findings from various studies, demonstrating the impact of this intervention on key endocrine and reproductive markers.

| Parameter | Baseline State in PCOS | Observed Change with 40:1 MI/DCI Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Ovulation Rate | Reduced or absent (oligo/anovulation). | Significant increase in spontaneous ovulation frequency; reduced time to first ovulation. |

| Serum Testosterone (Total & Free) | Elevated, contributing to clinical hyperandrogenism. | Statistically significant reduction. |

| Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) | Suppressed by hyperinsulinemia, increasing free androgen levels. | Significant increase, leading to reduced androgen bioavailability. |

| LH/FSH Ratio | Often elevated due to altered GnRH pulsatility. | Normalization of the ratio, indicating improved pituitary function. |

| Fasting Insulin & HOMA-IR | Elevated, indicating systemic insulin resistance. | Significant reduction, demonstrating improved insulin sensitivity. |

| Oocyte & Embryo Quality | Often compromised, with higher rates of immature oocytes. | Increased number of mature (MII) oocytes and higher-grade embryos in IVF cycles. |

The molecular rationale for combined inositol therapy is to replenish ovarian myo-inositol stores essential for FSH signaling while providing a modest amount of D-chiro-inositol to support systemic glucose metabolism without exacerbating intra-ovarian androgen production.

Current Standing in Clinical Guidelines

Despite the strong mechanistic rationale and positive results from numerous trials, the official stance from major endocrine bodies remains cautious. The 2023 International Evidence-Based Guideline for the Assessment and Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome, informed by a systematic review and meta-analysis, concluded that the overall quality of evidence for inositol is low to very low.

The report noted potential benefits for some metabolic markers but found that inositol may have no effect on other outcomes and that its impact on live birth rates remains uncertain. The guidelines emphasize that due to the “limited and inconclusive” evidence, the decision to use inositol should be a matter of shared decision-making between the clinician and the patient, taking individual health goals and preferences into account.

This contrasts with more established first-line treatments like combined oral contraceptives for cycle regulation or metformin for metabolic management in certain patient populations. The scientific community recognizes the promise and strong biological plausibility of inositol therapy, but a need persists for larger, high-quality, long-term randomized controlled trials to solidify its place in standard clinical practice guidelines. This highlights a common gap between emerging biochemical understanding and the high bar required for universal clinical recommendation.

The following list details the core molecular dysfunctions in the PCOS ovary that inositol therapy seeks to correct:

- MI Depletion ∞ Reduced availability of myo-inositol impairs the generation of MI-IPG second messengers, which are essential for the signal transduction of Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH), leading to poor follicular maturation.

- DCI Excess ∞ Overproduction of D-chiro-inositol from MI, driven by hyperinsulinemia, leads to an accumulation of DCI-IPG messengers that potentiate insulin’s steroidogenic effect on theca cells, increasing androgen synthesis.

- Aromatase Downregulation ∞ The hyperandrogenic microenvironment and impaired FSH signaling can lead to reduced activity of aromatase, the enzyme that converts androgens to estrogens, further disrupting follicular health.

References

- Unfer, V. et al. “The inositols and polycystic ovary syndrome.” World Journal of Diabetes, vol. 7, no. 11, 2016, pp. 228-35.

- Nordio, M. et al. “The 40:1 myo-inositol/D-chiro-inositol plasma ratio is able to restore ovulation in PCOS patients ∞ comparison with other ratios.” European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences, vol. 23, no. 12, 2019, pp. 5512-5521.

- Minozzi, M. et al. “The effect of a combination therapy with myo-inositol and D-chiro-inositol on endocrine parameters and insulin resistance in PCOS young overweight women.” International Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 2016, 2016, Article ID 3204083.

- Papaleo, E. et al. “Myo-inositol in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome ∞ A novel method for ovulation induction.” Gynecological Endocrinology, vol. 23, no. 12, 2007, pp. 700-3.

- Bevilacqua, A. and M. Bizzarri. “Physiological role and clinical utility of inositols in polycystic ovary syndrome.” Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, vol. 37, 2016, pp. 129-139.

- Genazzani, A. D. et al. “Myo-inositol administration positively affects hyperinsulinemia and hormonal parameters in overweight patients with polycystic ovary syndrome.” Gynecological Endocrinology, vol. 24, no. 3, 2008, pp. 139-44.

- Ciotta, L. et al. “Effects of myo-inositol supplementation on oocyte’s quality in PCOS patients ∞ a double blind trial.” European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences, vol. 15, no. 5, 2011, pp. 509-14.

- Greff, D. et al. “Inositol for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome ∞ A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis to Inform the 2023 Update of the International Evidence-based PCOS Guidelines.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 109, no. 6, 2024, pp. e2515-e2528.

- Legro, R. S. et al. “Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome ∞ an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 98, no. 12, 2013, pp. 4565-92.

Reflection

Integrating Knowledge into Your Personal Narrative

You have now journeyed through the intricate cellular mechanisms and clinical data surrounding inositol and its profound influence on ovarian function in PCOS. This knowledge is more than a collection of scientific facts; it is a new lens through which to view your own body and its unique physiology.

The feelings of frustration or confusion that may have characterized your health journey can now be met with a deeper understanding of the underlying biological conversations. You can begin to see symptoms not as random failures, but as logical, albeit unwelcome, consequences of a system operating under specific pressures like insulin resistance. This shift in perspective is the foundation of empowerment.

This information serves as a detailed map, but you are the ultimate navigator of your own terrain. The path forward involves observing how your body responds, tracking your own metabolic and hormonal patterns, and recognizing that wellness is a dynamic process of calibration.

The knowledge you’ve gained here equips you to ask more precise questions and to engage with healthcare providers as a partner in your own care. Your personal health journey is a unique narrative, and understanding the science behind it allows you to become its informed and empowered author, ready to write the next chapter with clarity and purpose.

Glossary

with polycystic ovary syndrome

inositol

women with pcos

second messenger

insulin resistance

follicle-stimulating hormone

ovarian function

fsh signaling

myo-inositol

d-chiro-inositol

peripheral tissues like muscle

systemic insulin resistance

ovarian paradox

theca cells

follicular development

hyperandrogenism

oocyte quality

inositol therapy

insulin sensitivity

polycystic ovary syndrome