Fundamentals

The feeling of being at odds with your own body is a profound and often isolating experience. When you live with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), this feeling can become a daily reality, a persistent hum of symptoms that disrupt your sense of well-being.

You may recognize the irregular cycles, the frustrating changes in your skin or hair, or the persistent fatigue that defies a full night’s sleep. These are not isolated events; they are the outward expression of a complex internal environment. Your experience is valid, and it is rooted in your unique biology. Understanding this biology is the first step toward reclaiming agency over your health.

At the center of the PCOS constellation is a physiological state called insulin resistance. Insulin is a powerful hormone, a key that is meant to unlock your cells, allowing them to absorb glucose from your bloodstream for energy. In a state of insulin resistance, your cells become less responsive to this key.

Your pancreas, sensing that the cells are starving for glucose, compensates by producing even more insulin. This cascade of elevated insulin creates significant downstream effects, particularly on the ovaries. The high levels of insulin stimulate the ovaries to produce an excess of androgens, such as testosterone. This hormonal shift is what drives many of the visible and internal symptoms of PCOS, from acne and hirsutism to the disruption of ovulation.

PCOS originates from a core metabolic disruption, where cellular resistance to insulin sets off a chain reaction that alters ovarian function and hormonal balance.

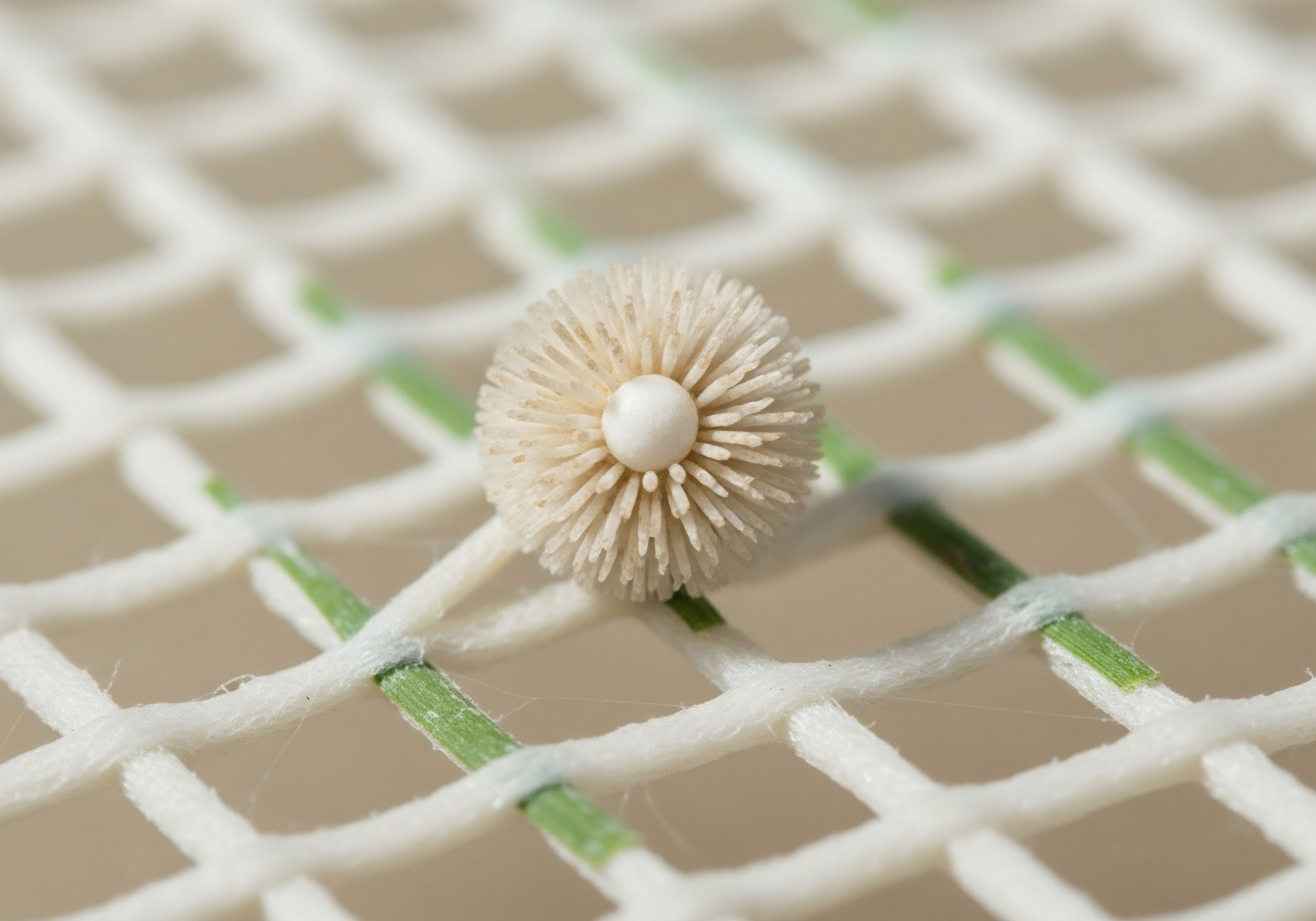

This entire process is a conversation happening within your endocrine system, the body’s intricate communication network. Think of it as a finely tuned orchestra where each instrument must play in time and at the correct volume.

In PCOS, high insulin levels are like a single section playing far too loudly, forcing the other sections, particularly the ovaries, to respond in a way that creates disharmony. The goal of any effective, long-term therapeutic approach is to restore the orchestra’s balance. This involves addressing the root cause of the disruption, the insulin resistance itself, which allows the rest of the system to recalibrate.

What Is Inositol’s Role in Cellular Communication?

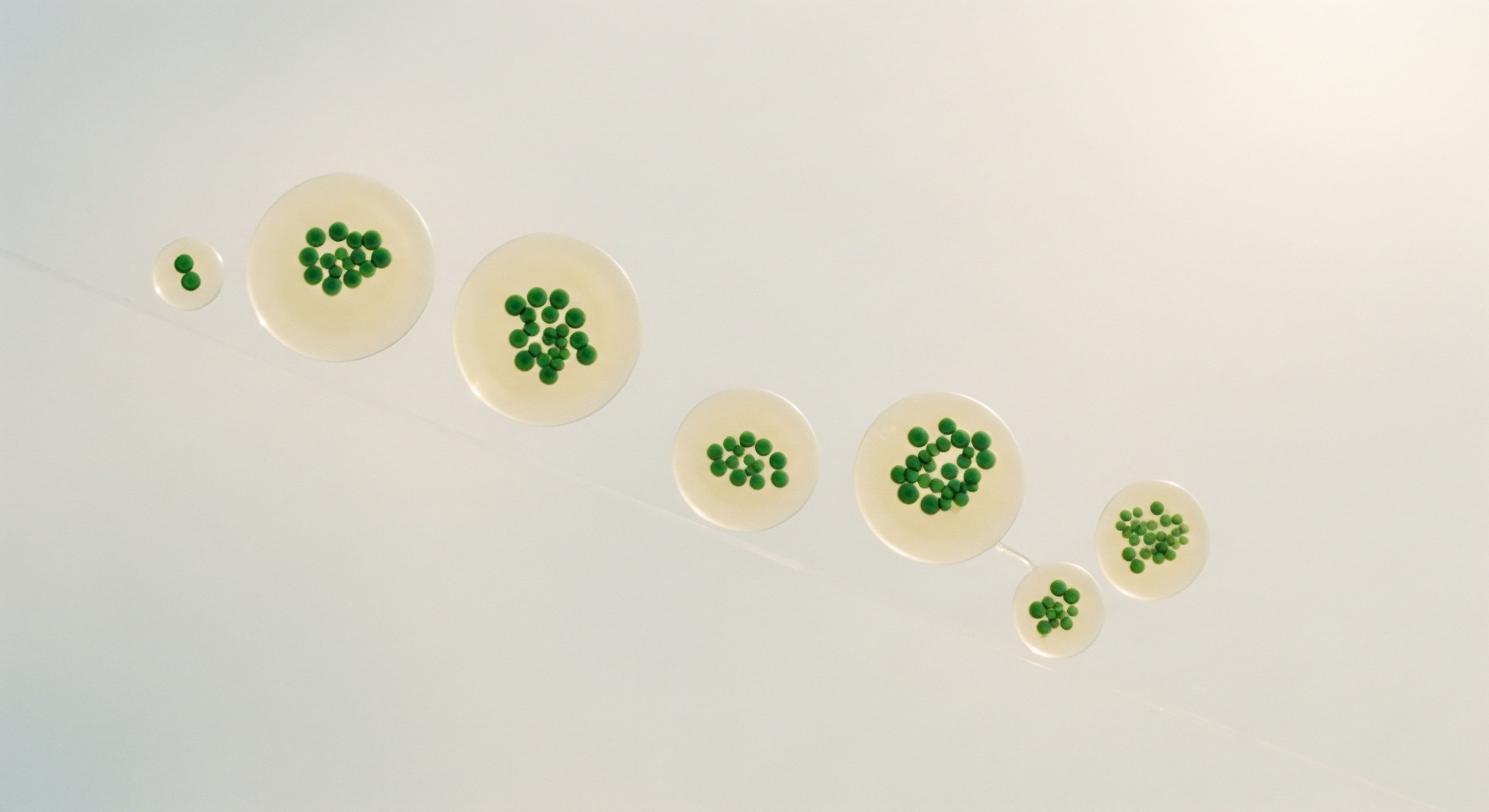

Within this context, inositol emerges as a compelling therapeutic molecule because it works at the very level where this communication breaks down. Inositol is a type of sugar alcohol, a carbocyclic polyol, that is naturally present in our bodies and in many foods. It acts as a “second messenger” within our cells.

When the primary messenger, insulin, binds to its receptor on the cell surface, it triggers the release of inositol-based molecules inside the cell. These molecules then carry the signal forward, instructing the cell to take up glucose. In individuals with PCOS, there appears to be a defect in this signaling pathway.

Supplementing with specific forms of inositol, primarily myo-inositol and D-chiro-inositol, provides the raw materials needed to repair this broken communication link. It helps restore the cell’s sensitivity to insulin, quieting the demand on the pancreas and, in turn, reducing the stimulus for the ovaries to overproduce androgens. This approach supports the body’s own biochemistry, aiming to correct the signaling pathway rather than overriding it with external forces.

Intermediate

Understanding the foundational role of insulin resistance in PCOS allows for a more sophisticated evaluation of long-term treatment strategies. The choice of therapy depends on a nuanced assessment of an individual’s specific metabolic and reproductive goals. The three primary therapeutic avenues ∞ inositol, metformin, and oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) ∞ each interact with the body’s systems in fundamentally different ways.

Their long-term outcomes are a direct reflection of these distinct mechanisms of action. A durable solution requires a protocol that aligns with your body’s specific needs, addressing the underlying metabolic dysfunction while supporting your overall well-being.

Inositol a Cellular Signal Restoration

Inositol’s therapeutic power lies in its function as a secondary messenger in the insulin signaling cascade. The body utilizes several stereoisomers of inositol, with myo-inositol (MI) and D-chiro-inositol (DCI) being the most critical for metabolic health. Each tissue maintains a specific MI to DCI ratio, which is essential for proper function.

Mechanism of Action

When insulin binds to its receptor on a cell, it activates enzymes that convert MI into inositol phosphoglycans (IPGs). These IPGs then signal the cell’s glucose transporters (like GLUT4) to move to the cell surface and begin absorbing glucose from the blood. In PCOS, a deficiency or impaired conversion of these inositols can disrupt this process.

Supplementation with a physiological ratio of MI to DCI (typically 40:1) aims to replenish these intracellular messengers, directly improving insulin sensitivity at the cellular level. This targeted action helps normalize glucose metabolism and consequently lowers circulating insulin levels. The reduction in insulin directly lessens the stimulation of ovarian theca cells, leading to decreased androgen production.

Long-Term Outcomes and Considerations

Studies suggest that long-term supplementation with inositol can lead to sustained improvements in metabolic markers, including fasting insulin and HOMA-IR. This metabolic recalibration supports the restoration of regular menstrual cycles and ovulation in many individuals.

Because inositol works by supporting the body’s natural signaling pathways, it is generally well-tolerated with a very low side-effect profile, primarily mild gastrointestinal upset at high doses. This high tolerability is a significant factor in long-term adherence. The evidence for its impact on body mass index (BMI) is less conclusive, with some studies showing a modest reduction while others find no significant change.

Metformin a Systemic Metabolic Modulator

Metformin is a biguanide-class medication and one of the most prescribed drugs for type 2 diabetes. Its application in PCOS stems from its potent effects on systemic glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity. It has been a cornerstone of PCOS management for decades.

Mechanism of Action

Metformin’s primary mechanism involves the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a central regulator of cellular energy homeostasis. By activating AMPK, metformin reduces the liver’s production of glucose (gluconeogenesis) and increases glucose uptake in peripheral tissues like muscle. This dual action effectively lowers blood glucose and insulin levels.

This systemic effect helps to correct the hyperinsulinemia that drives ovarian androgen excess in PCOS. Its action is independent of the inositol pathway, representing a different biochemical approach to the same problem.

Long-Term Outcomes and Considerations

Long-term use of metformin can produce durable improvements in the metabolic profile of women with PCOS, including reductions in BMI and improvements in HDL cholesterol. It has been shown to reduce the long-term risk of developing type 2 diabetes. For reproductive health, metformin is effective in improving menstrual regularity and can be used to induce ovulation.

The primary challenge with metformin is its side-effect profile. A significant percentage of users experience gastrointestinal side effects, such as nausea, diarrhea, and abdominal discomfort, which can impact long-term adherence. While often mild and transient, these effects can be a barrier for some individuals.

Oral Contraceptives a Hormonal Regulation Strategy

Oral contraceptive pills are a first-line therapy for managing the hyperandrogenic symptoms and menstrual irregularities of PCOS, especially for individuals who do not wish to conceive. They operate by introducing external hormones to regulate the endocrine system.

Mechanism of Action

Combination OCPs contain synthetic estrogen and progestin. The estrogen component suppresses the pituitary gland’s production of Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH), preventing follicular development in the ovaries. It also increases the liver’s production of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG). SHBG binds to free testosterone in the bloodstream, reducing the amount of biologically active androgen.

The progestin component suppresses the pituitary’s Luteinizing Hormone (LH) surge, preventing ovulation, and also directly inhibits ovarian androgen production. This combined action imposes a regular withdrawal bleed and effectively manages symptoms of androgen excess.

Long-Term Outcomes and Considerations

OCPs are highly effective for cycle regulation and reducing hirsutism and acne. By ensuring regular shedding of the uterine lining, they also provide crucial protection against endometrial hyperplasia and cancer, a significant long-term risk in anovulatory individuals. The long-term considerations for OCPs are primarily metabolic.

They do not address the root cause of insulin resistance. Some formulations may have neutral or even slightly adverse effects on glucose tolerance and lipid profiles. There is also an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), which must be carefully assessed based on individual risk factors like age, smoking, and obesity.

Effective long-term PCOS management hinges on selecting a therapy that aligns with individual goals, whether that is restoring cellular signaling with inositol, modulating systemic metabolism with metformin, or regulating hormonal symptoms with contraceptives.

| Feature | Inositol | Metformin | Oral Contraceptives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Restores intracellular insulin signaling (second messenger). | Reduces hepatic glucose output and improves peripheral glucose uptake via AMPK activation. | Suppresses pituitary hormones (LH/FSH) and increases SHBG to lower active androgens. |

| Effect on Insulin Resistance | Directly improves cellular insulin sensitivity. | Systemically lowers insulin and glucose levels. | Does not treat insulin resistance; may have variable effects. |

| Reproductive Effects | Restores spontaneous ovulation and menstrual regularity. | Improves ovulation rates and menstrual regularity. | Induces regular withdrawal bleeds; prevents ovulation. |

| Hyperandrogenism | Reduces androgens secondary to insulin reduction. | Reduces androgens secondary to insulin reduction. | Directly reduces androgen symptoms by increasing SHBG and suppressing ovarian production. |

| Common Side Effects | Minimal; mild GI upset at high doses. | High incidence of GI side effects (nausea, diarrhea). | Mood changes, headaches, increased VTE risk. |

The choice between these therapies is a clinical decision based on a comprehensive view of the patient’s life stage, goals, and metabolic health. For an individual focused on restoring natural metabolic function and fertility with minimal side effects, inositol presents a very strong case.

For someone with more significant metabolic disease or where inositol is insufficient, metformin is a powerful and well-evidenced tool. For a person prioritizing symptom management and contraception, OCPs are highly effective. In some cases, these therapies may be used in combination to achieve synergistic effects.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of long-term therapeutic outcomes in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome requires moving beyond symptom management to a detailed examination of the molecular and systemic interactions of each intervention. The divergent paths of inositol, metformin, and oral contraceptives illuminate distinct philosophies of treatment. Inositol seeks to restore endogenous signaling fidelity.

Metformin acts as a powerful systemic metabolic switch. Oral contraceptives impose an external regulatory control over the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. The long-term trajectory of health for an individual with PCOS is profoundly influenced by which of these paths is chosen, as their effects ripple through interconnected physiological systems.

How Does Inositol Recalibrate Ovarian Function?

The therapeutic effect of inositol is rooted in its role as a precursor to inositol phosphoglycan (IPG) second messengers. The insulin receptor is a tyrosine kinase; its activation upon insulin binding initiates a phosphorylation cascade. A key substrate in this cascade is the family of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases (PI3K), which depends on a supply of membrane-bound phosphoinositides.

In PCOS, defects in the epimerase enzyme that converts myo-inositol (MI) to D-chiro-inositol (DCI) can lead to tissue-specific deficiencies. The ovary, which requires a high MI-to-DCI ratio for proper FSH signaling and oocyte development, becomes paradoxically DCI-depleted in a systemic state of hyperinsulinemia.

Meanwhile, the insulin-sensitive tissues like muscle and fat become MI-depleted. Supplementing with a 40:1 MI/DCI ratio provides the necessary substrates to the correct tissues. This restores insulin action in peripheral tissues, lowering systemic insulin. Concurrently, it maintains the high MI environment needed by the ovary to respond appropriately to FSH, supporting follicular maturation and oocyte quality. This dual action corrects the core metabolic lesion while simultaneously supporting gonadal function, a uniquely targeted approach.

The long-term efficacy of any PCOS therapy is ultimately determined by its ability to interact with the body’s complex metabolic and endocrine feedback loops.

Metformin’s mechanism, while also addressing hyperinsulinemia, is fundamentally different. Its activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) positions it as a master metabolic regulator. AMPK activation inhibits anabolic processes that consume ATP (like gluconeogenesis and lipid synthesis) and stimulates catabolic processes that generate ATP (like fatty acid oxidation and glucose uptake).

In the liver, this leads to a marked decrease in glucose production, a primary contributor to the reduction in fasting glucose and insulin levels. In the ovary, AMPK activation can also inhibit aromatase expression and steroidogenesis, contributing to the reduction in androgen levels.

This represents a powerful, systemic intervention that improves the overall energy economy of the body. The long-term benefit is a reduction in the metabolic load that contributes to the progression of comorbidities like type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

| Therapeutic Agent | Primary Molecular Target | Effect on HPG Axis | Long-Term Metabolic Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inositol (MI/DCI) | IPG second messenger system; PI3K pathway substrate. | Restores ovarian sensitivity to FSH; reduces insulin-driven LH stimulation. | Improved insulin sensitivity through enhanced intracellular signaling. |

| Metformin | AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). | Reduces insulin-driven ovarian steroidogenesis; may improve GnRH pulsatility. | Reduced hepatic gluconeogenesis and improved systemic energy metabolism. |

| Oral Contraceptives | GnRH pulse generator; pituitary gonadotropes. | Exogenous suppression of GnRH, LH, and FSH; overrides endogenous feedback. | Does not address underlying insulin resistance; potential for altered lipid profiles. |

How Do Oral Contraceptives Alter Endocrine Feedback?

Oral contraceptives take a third, distinct approach by imposing a state of hormonal dominance that overrides the dysfunctional endogenous feedback loops of the HPG axis. The constant, non-pulsatile administration of synthetic estrogen and progestin suppresses the hypothalamic GnRH pulse generator. This, in turn, flattens pituitary secretion of LH and FSH, placing the ovaries in a quiescent state.

The long-term outcome is effective management of symptoms driven by androgen excess and anovulation. The crucial point from a systems biology perspective is that this is a suppressive therapy. It manages the downstream consequences of PCOS without altering the upstream metabolic driver.

For long-term health, this means that while the risk of endometrial cancer is reduced and quality of life from a symptomatic standpoint is improved, the underlying insulin resistance persists and may require separate management to mitigate the risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

- Inositol ∞ Aims for physiological restoration. The long-term goal is a self-regulating system where endogenous insulin signaling and ovarian function are normalized. Its success is measured by the return of spontaneous, healthy biological rhythms.

- Metformin ∞ Functions as a metabolic intervention. The long-term objective is to reduce the systemic metabolic burden, thereby preventing the progression to more severe metabolic disease. Its success is tracked through markers like HbA1c, lipid panels, and BMI.

- Oral Contraceptives ∞ Act as a form of hormonal regulation. The long-term goal is the prevention of endometrial pathology and the management of clinical hyperandrogenism. Its success is defined by regular withdrawal bleeding and control of symptoms like hirsutism and acne.

The selection of a long-term therapy for PCOS, therefore, represents a strategic choice about how to interact with a complex biological system. Inositol offers a path of restoration, metformin a path of intervention, and OCPs a path of regulation. A truly personalized and sustainable protocol may involve one or a combination of these approaches, guided by an individual’s specific phenotype, life goals, and the ongoing dialogue between their metabolic and endocrine systems.

References

- Greff, D. et al. “Inositol is an effective and safe treatment in polycystic ovary syndrome ∞ a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.” Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology, vol. 21, no. 1, 2023, p. 10.

- Teede, H. et al. “Inositol for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome ∞ A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis to Inform the 2023 Update of the International Evidence-based PCOS Guidelines.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 108, no. 10, 2023, pp. 2649 ∞ 2661.

- Pundir, J. et al. “Myo-inositol effects in women with PCOS ∞ a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.” Endocrine Connections, vol. 7, no. 1, 2018, pp. R9-R11.

- Moghetti, P. et al. “Evidence-Based and Potential Benefits of Metformin in the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome ∞ A Comprehensive Review.” Endocrine Reviews, vol. 41, no. 2, 2020, pp. 231-251.

- Jensterle, M. et al. “Long-term efficacy of metformin in overweight-obese PCOS ∞ longitudinal follow-up of retrospective cohort.” Endocrine Connections, vol. 9, no. 2, 2020, pp. 169-178.

- Lord, J. M. et al. “Metformin in polycystic ovary syndrome ∞ systematic review and meta-analysis.” BMJ, vol. 327, no. 7421, 2003, pp. 951-953.

- Yilmaz, B. et al. “An Update on Contraception in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 35, no. 1, 2020, pp. 24-36.

- Yao, Y. et al. “Different kinds of oral contraceptive pills in polycystic ovary syndrome ∞ a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Human Reproduction Update, vol. 29, no. 2, 2023, pp. 149-163.

- Le, K. & Laganà, A. S. “The effects of myo-inositol vs. metformin on the ovarian function in the polycystic ovary syndrome ∞ a systematic review and meta-analysis.” European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences, vol. 25, no. 7, 2021, pp. 3127-3140.

- Tagliaferri, V. et al. “Comparison of metformin with inositol versus metformin alone in women with polycystic ovary syndrome ∞ a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.” Gynecological Endocrinology, vol. 38, no. 10, 2022, pp. 806-812.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a map of the biological terrain of PCOS and the tools available to navigate it. This knowledge is powerful. It transforms the conversation from one of managing disparate symptoms to one of understanding and supporting an interconnected system.

Your body is constantly communicating its needs through the language of hormones and metabolic signals. The path forward involves learning to listen to that language with clarity and precision. Consider where your personal health journey is currently situated on this map. What are your immediate and long-term goals?

The answers to these questions are the starting point for a personalized dialogue with a clinical guide, one that uses this scientific foundation to build a protocol that is uniquely yours. Your biology is not your destiny; it is your starting point for a journey toward profound well-being.