Fundamentals

You track your symptoms, sleep patterns, and daily nutrition in a wellness application, believing you are assembling a comprehensive dataset for your own benefit and perhaps for your next clinical consultation. The information feels personal, vital, and contained within the digital walls of the app.

A fundamental disconnect exists, however, between the data held by your physician and the information you entrust to a commercial wellness platform. The moment you input data into a third-party app, it often crosses an invisible, yet critical, regulatory boundary. Understanding this distinction is the foundational step toward taking full ownership of your sensitive health information and navigating your wellness journey with intention and security.

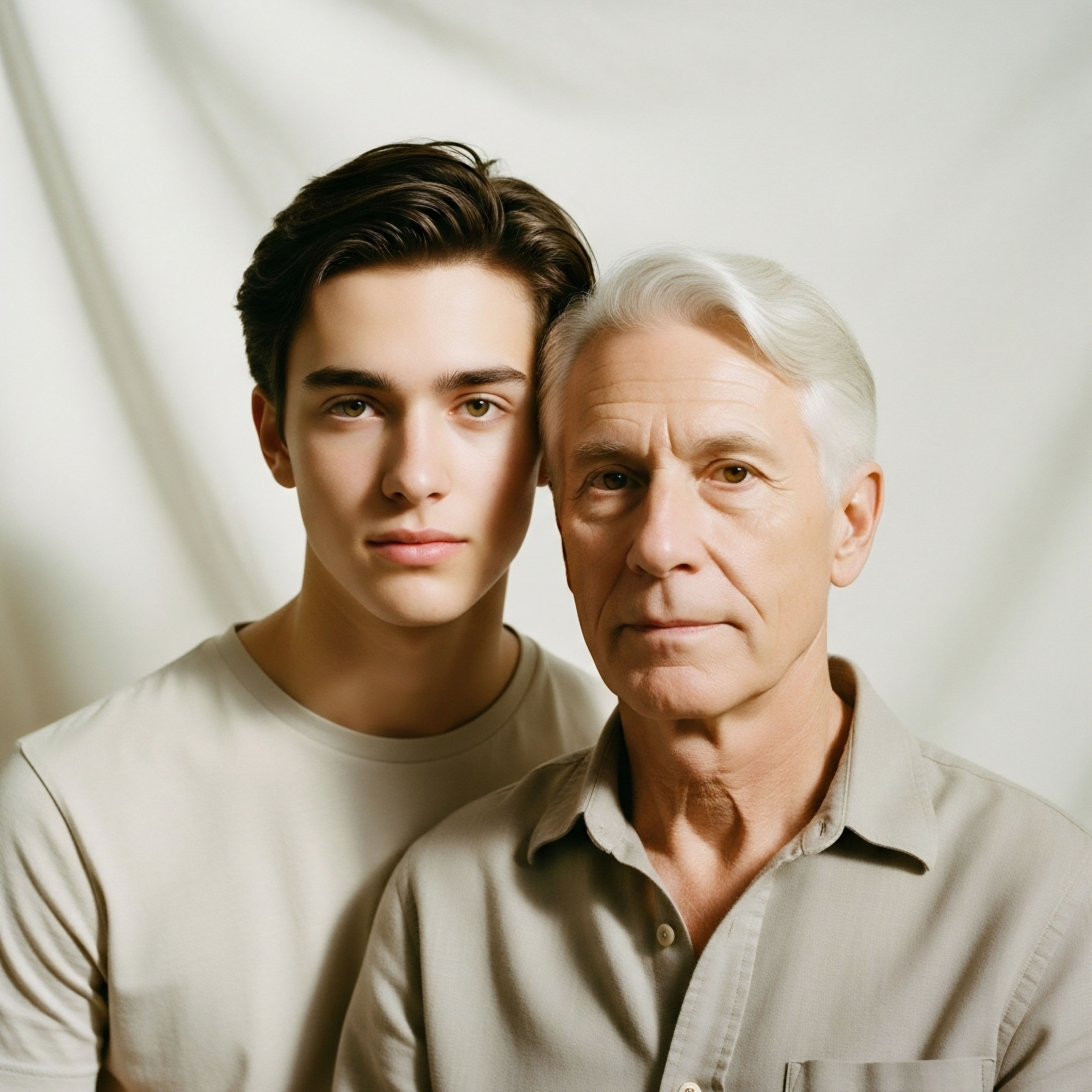

The system that protects your health information within a clinical setting is defined by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or HIPAA. This federal law establishes a protected space for your medical records. Think of it as a clearly defined “circle of trust” that legally binds specific individuals and organizations to safeguard your data.

The entities operating within this circle are known as “covered entities.” These are your doctors, hospitals, clinics, and health insurance plans. When they create, receive, or transmit information about your health, that information is designated as Protected Health Information (PHI).

PHI includes not just diagnoses or lab results, but also your name, address, and any other identifier that links you to your health status. The rules governing this circle are strict, dictating who can see your information, why they can see it, and how it must be protected.

HIPAA’s protections apply specifically to “covered entities,” such as healthcare providers and health plans, and their “business associates.”

Most wellness and fitness apps that you download and use independently exist outside of this designated circle of trust. A company that develops a nutrition tracker or a sleep monitor directly for consumers is generally not considered a covered entity.

Therefore, the data you provide ∞ your daily caloric intake, your mood fluctuations, your heart rate during exercise ∞ is not classified as PHI under HIPAA’s definition. This information, while deeply personal and health-related, falls into a different category often called “healthcare adjacent data.” It lives in a commercial ecosystem governed by a different set of rules, primarily those enforced by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).

The privacy policy of the app, which you agree to upon signing up, becomes the primary document outlining how your data can be used, shared, or sold. This creates a completely different dynamic of data ownership and control compared to the legally mandated protections of a clinical environment.

What Defines a Covered Entity

To understand the application of HIPAA, one must first identify the players bound by its rules. A covered entity is the cornerstone of this regulatory framework. The designation is quite specific and is not based on the type of data handled, but on the nature of the organization itself. There are three main categories of covered entities:

- Healthcare Providers This category includes physicians, clinics, psychologists, dentists, chiropractors, nursing homes, and pharmacies. The key condition is that they transmit health information in electronic form in connection with a transaction for which the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has adopted standards.

- Health Plans These are health insurance companies, Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs), company health plans, and government programs that pay for health care, such as Medicare, Medicaid, and military and veterans’ health care programs.

- Healthcare Clearinghouses These are entities that process nonstandard health information they receive from another entity into a standard format (or vice versa). An example would be a billing service that translates claims from one format to another.

If an organization does not fall into one of these three categories, it is not a HIPAA covered entity. This is why most direct-to-consumer wellness app developers are not bound by HIPAA’s requirements. They are not your healthcare provider, they are not your insurance plan, and they are not processing claims on your behalf. They are technology companies providing a service directly to you, the consumer, placing them outside that protected circle of trust from the outset.

The Role of Business Associates

The protective sphere of HIPAA extends one layer beyond covered entities through the concept of a “business associate.” A business associate is a person or organization that performs certain functions or activities on behalf of a covered entity, which involve the use or disclosure of PHI.

For example, a third-party company that handles billing, data analysis, or cloud storage for a hospital is a business associate. An app developer can become a business associate, and thus subject to HIPAA, if it enters into a contract with a covered entity.

Imagine your doctor’s office offers a specific mobile app for you to track your blood pressure at home, and the data from that app feeds directly into your electronic health record (EHR) for your physician to review. In this scenario, the app developer has been contracted by the healthcare provider (a covered entity) to handle PHI.

The developer is now a business associate and is required to sign a Business Associate Agreement (BAA). This is a legally binding contract that obligates the developer to implement the same kinds of safeguards for your information that the doctor’s office must. This distinction is critical. The determining factor is the flow of information and the relationship between the app developer and the covered entity, not just the functionality of the app itself.

Intermediate

The distinction between the data ecosystems of your doctor’s office and a wellness app becomes clearer when examining their respective regulatory frameworks. Your relationship with your physician is governed by the rigorous and specific mandates of the HIPAA Privacy and Security Rules. These rules are designed with the primary goal of protecting patient health information.

The world of consumer wellness apps operates under a different authority, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which focuses on protecting consumers from unfair or deceptive business practices, including misleading statements about data privacy. A recent and significant tool in the FTC’s arsenal is the Health Breach Notification Rule (HBNR), which has been clarified to apply directly to most health and wellness apps.

The HIPAA Privacy Rule establishes national standards for the protection of individuals’ medical records and other individually identifiable health information. It sets limits and conditions on the uses and disclosures that may be made of such information without patient authorization.

The rule gives you rights over your health information, including the right to examine and obtain a copy of your health records and to request corrections. The Security Rule complements the Privacy Rule. It requires covered entities and their business associates to implement administrative, physical, and technical safeguards to ensure the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of electronic PHI.

This includes measures like access controls, encryption, and audit trails to monitor who is accessing the data. These rules create a robust structure designed to foster trust in the healthcare system.

While HIPAA establishes a baseline for protecting PHI held by covered entities, the FTC’s Health Breach Notification Rule mandates consumer notification when unsecured health data is breached by non-HIPAA-covered apps and services.

In contrast, the FTC’s authority is broader and less focused on the specific clinical nature of the data. The HBNR requires vendors of personal health records (PHRs) and related entities that are not covered by HIPAA to notify individuals, the FTC, and sometimes the media, of a breach of unsecured identifiable health information.

A “breach” under this rule is defined more broadly than a typical cybersecurity incident; it includes any unauthorized acquisition of identifiable health information that occurs as a result of a data security breach or an unauthorized disclosure.

This means if an app shares your data with a third party like an advertising company without your clear authorization, it could be considered a breach under the HBNR. This rule is a significant step in closing the regulatory gap, but its focus is on notification after the fact, a different function from HIPAA’s preventative privacy and security mandates.

How Do the Regulatory Frameworks Compare

A direct comparison reveals the fundamental differences in how your data is treated in these two environments. The protections afforded by HIPAA are proactive and systemic, integrated into the very fabric of how a clinical practice operates. The protections from the FTC are largely reactive, centered on transparency and accountability after a potential misuse has occurred. Understanding these differences is essential for making informed decisions about where you log your most sensitive health information.

The following table illustrates the contrasting obligations and protections under each regulatory authority, providing a clear view of the two worlds your health data can inhabit.

| Feature | Doctor’s Office (HIPAA) | Wellness App (FTC & HBNR) |

|---|---|---|

| Governing Body | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) | Federal Trade Commission (FTC) |

| Primary Legislation | Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) | FTC Act & Health Breach Notification Rule (HBNR) |

| Who Is Covered | Healthcare providers, health plans, and healthcare clearinghouses (“covered entities”) and their “business associates.” | Vendors of personal health records (PHRs) and PHR-related entities not covered by HIPAA. This includes most health and wellness apps. |

| What Data Is Protected | Protected Health Information (PHI) ∞ Individually identifiable health information created or received by a covered entity. | PHR Identifiable Health Information ∞ Individually identifiable health information in a personal health record. The definition is broad and includes data inferred from location or purchases. |

| Rules on Data Use/Sharing | Strictly limited to treatment, payment, and healthcare operations. Most other uses and disclosures require explicit patient authorization. The “minimum necessary” standard applies. | Governed by the app’s privacy policy and terms of service. Sharing data with third parties (e.g. for advertising) is common and may be considered a “breach” if not properly authorized. |

| Breach Notification Requirement | Must notify affected individuals, HHS, and sometimes the media following a breach of unsecured PHI. Deadlines are specific (e.g. without unreasonable delay and no later than 60 days). | Must notify affected individuals, the FTC, and sometimes the media following a breach. A “breach” includes unauthorized sharing. Deadlines are similar (without unreasonable delay and no later than 60 days). |

| Patient/User Rights | Right to access, amend, and receive an accounting of disclosures of PHI. | Rights are defined by the company’s privacy policy and applicable state laws (like the CCPA). The HBNR provides the right to be notified of a breach. |

What Is the Impact of Unauthorized Data Sharing

The consequences of unauthorized data sharing differ profoundly between the two ecosystems. In a HIPAA-protected environment, an impermissible disclosure of PHI is a violation of federal law, carrying significant financial penalties for the covered entity and potential legal recourse for the patient. The structure is designed to prevent such disclosures from happening in the first place.

In the wellness app ecosystem, the concept of “sharing” is often built into the business model. Many free or low-cost apps generate revenue by sharing or selling aggregated or even user-level data with third parties, including data brokers, advertisers, and research firms.

While the FTC has taken action against companies for sharing data in ways that contradict their privacy policies, the practice itself is not inherently illegal if disclosed in the fine print of a user agreement. The recent enforcement of the HBNR makes it clear that sharing this data without consent constitutes a breach requiring notification.

For instance, the FTC has penalized companies like GoodRx and BetterHelp for sharing sensitive health data with platforms like Facebook and Google for advertising purposes. This action signals a more aggressive regulatory stance, but it also highlights the fundamental difference ∞ in the app world, your health data is often a commodity.

This can lead to your information being used to build a detailed consumer profile about you, influencing the ads you see and potentially having downstream effects on other aspects of your life.

Academic

From a systems-biology perspective, an individual’s endocrine and metabolic status represents a dynamic and deeply sensitive dataset. The complex interplay of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, thyroid function, adrenal output, and insulin sensitivity creates a unique biochemical signature.

When a patient undertakes a personalized wellness protocol, such as Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) for andropause or Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) for perimenopause, the data they generate ∞ both from clinical lab work and subjective symptom tracking ∞ is of paramount clinical importance. The integrity and context of this data are everything.

Within the sanctuary of a HIPAA-covered clinical relationship, this information is contextualized with a physician’s expertise. Outside of it, in the world of commercial wellness apps, this same data becomes de-contextualized, fragmented, and vulnerable to commercial exploitation with significant potential for harm.

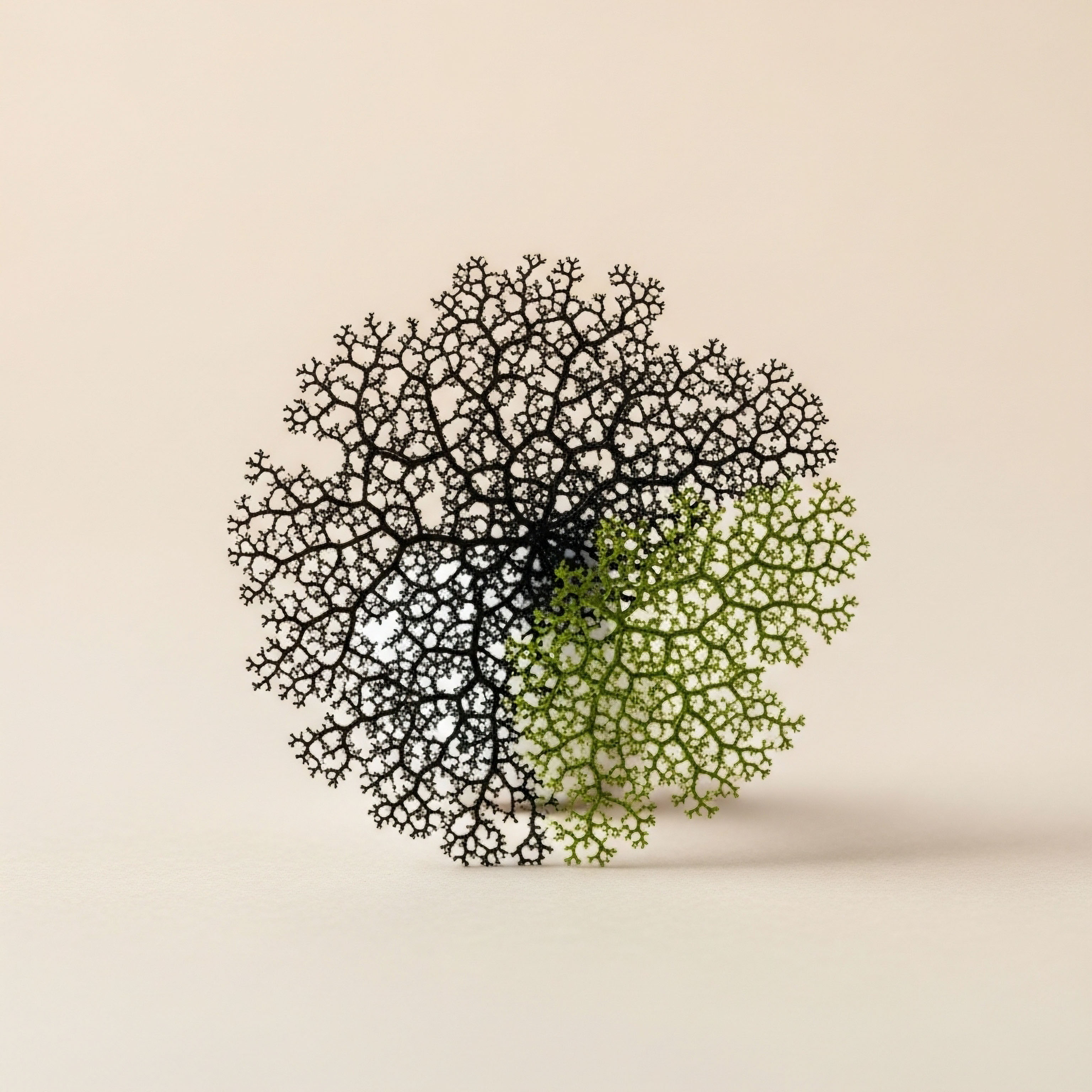

The primary danger lies in the process of data aggregation and re-identification. A wellness app may collect information that seems innocuous in isolation ∞ sleep duration, daily mood scores, menstrual cycle dates, or dietary habits. However, when this data is sold to data brokers, it can be combined with other commercially available datasets ∞ credit card purchases, location history, social media activity, and public records.

Advanced algorithms can then analyze these combined datasets to infer highly sensitive health conditions. For example, a combination of irregular cycle data from a period tracker, location data showing visits to a fertility clinic, and purchase history including prenatal vitamins could allow a data broker to build a profile of someone trying to conceive.

This profile can be sold to advertisers or other entities without the individual’s knowledge or consent. This re-identification risk transforms user-generated data from a personal health tool into a powerful commercial surveillance asset.

The sale and aggregation of “anonymized” health data from apps create a significant risk of re-identification, where users can be linked back to sensitive inferred health conditions.

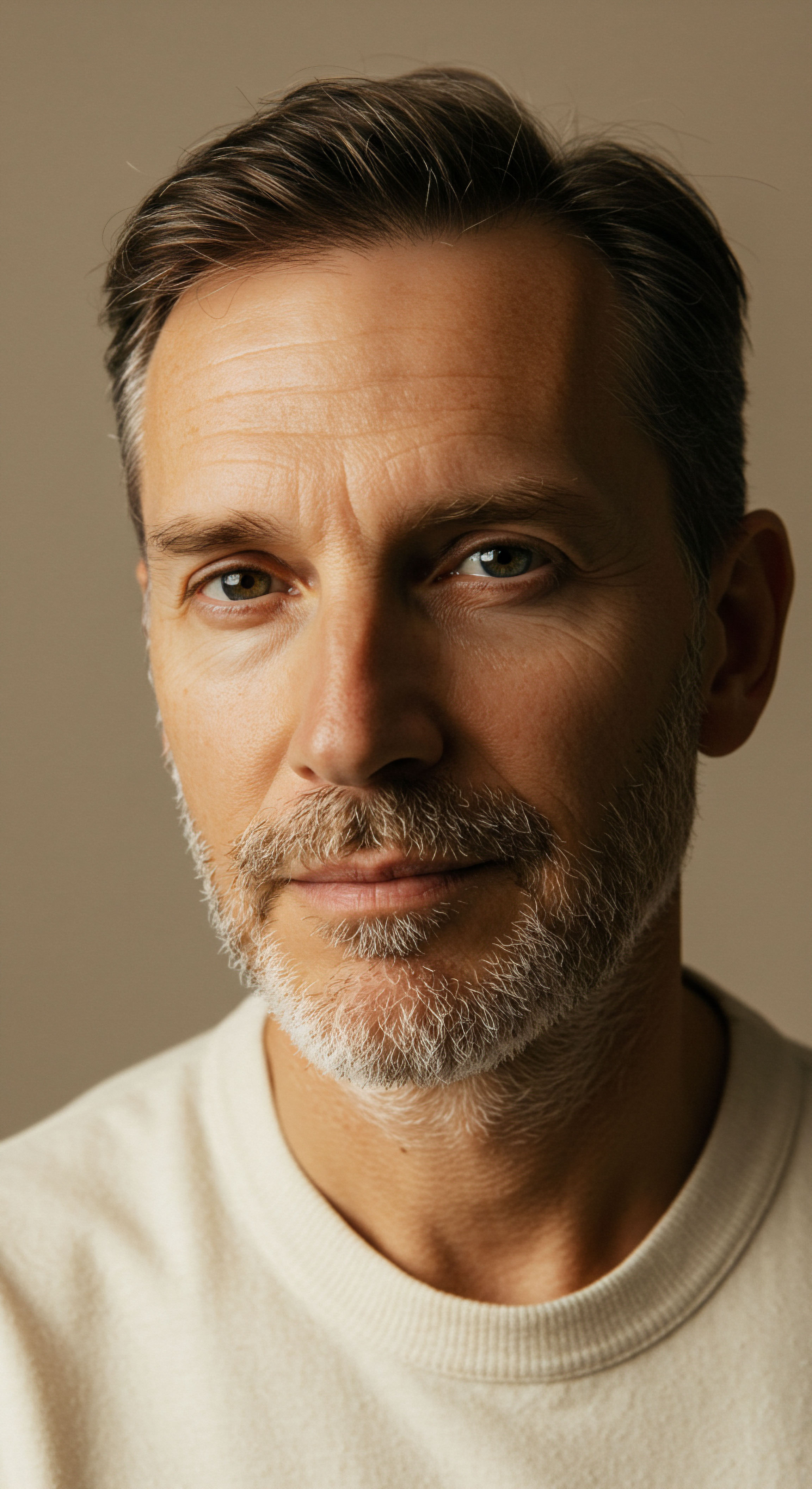

This has profound implications for individuals on specific hormonal protocols. Consider a man on a TRT protocol, which may include weekly injections of Testosterone Cypionate, along with Gonadorelin to maintain testicular function and an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole to manage estrogen. He might use an app to track injection dates, energy levels, libido, and workout performance.

If this app’s data is breached or sold, it could be used to infer his specific medical treatment. This information could lead to targeted advertising for unverified supplements, but it could also result in social stigma or discriminatory practices in contexts not covered by existing health privacy laws.

Similarly, a woman using a low-dose testosterone cream, progesterone, and a peptide like Ipamorelin for wellness and vitality could have her data used to build a profile that marks her as “aging” or “hormonally imbalanced,” influencing the commercial messaging and opportunities she is exposed to.

How Does Data Provenance Affect Clinical Decisions

Another critical issue from a clinical standpoint is data provenance and accuracy. The data within a patient’s Electronic Health Record (EHR) at a doctor’s office comes from validated sources ∞ accredited laboratories performing blood assays, calibrated medical devices, and direct clinical observation. When a physician adjusts a patient’s Anastrozole dose, it is based on a quantitative estradiol lab result, correlated with the patient’s reported symptoms. There is a high degree of confidence in the data’s reliability.

Patient-generated health data (PGHD) from consumer apps lacks this clinical validation. A heart rate measurement from a fitness tracker may not have the same accuracy as an ECG in a clinical setting. A mood score in an app is subjective and can be influenced by myriad factors.

While this PGHD can be a valuable addition to the clinical picture, a physician must approach it with caution. The danger arises when a patient or an unregulated entity places the same value on unvalidated PGHD as on clinical diagnostics.

This can lead to poor decision-making, such as altering a prescribed hormone dose based on an inaccurate sleep score from a consumer device. The HIPAA-covered environment provides a necessary filter, where a trained clinician can integrate PGHD thoughtfully, using it to supplement, rather than supplant, validated clinical data.

This curated approach is essential for safely managing complex protocols like post-TRT fertility stimulation (using agents like Gonadorelin, Clomid, and Tamoxifen) or Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy, where precise monitoring is key to achieving desired outcomes and avoiding adverse effects.

Data Risks in Hormonal Health Management

The specific data points collected by wellness apps can create unique vulnerabilities when viewed through the lens of hormonal and metabolic health. The table below explores some of these data points, the potential inferences that can be drawn by third parties, and the stark contrast with how that same data is protected and utilized within a clinical setting.

| App-Collected Data Point | Potential Inference in Commercial Use | Use and Protection in a Clinical (HIPAA) Setting |

|---|---|---|

| Menstrual Cycle Tracking | Inferences about perimenopause, menopause, fertility issues, or pregnancy. Can be sold to advertisers for targeted products or services. | Used by a gynecologist or endocrinologist to diagnose and manage conditions like PCOS or hormonal imbalances. Protected as PHI. |

| Sleep & HRV Data | Can be used to infer high stress levels, poor recovery, or potential sleep disorders. Marketed to sellers of sleep aids, supplements, or wellness retreats. | Considered alongside lab work (e.g. cortisol levels) to assess HPA axis function and guide treatment. Data is part of the confidential medical record. |

| Libido & Sexual Function Tracking | Highly sensitive data used to infer relationship status, sexual dysfunction, or interest in specific treatments (e.g. for ED). Can lead to highly targeted, potentially embarrassing advertising. | A key subjective marker discussed confidentially with a physician to assess the efficacy of protocols like TRT or peptide therapies like PT-141. Protected as PHI. |

| Workout & Injection Logging | Can infer the use of performance-enhancing substances or specific medical protocols like TRT or peptide therapy. This information could be stigmatizing. | Used to monitor patient adherence and correlate therapeutic response with a prescribed protocol. All details are part of the protected treatment plan. |

| Mood & Anxiety Scores | Aggregated to create psychological profiles for targeted advertising of mental health services or products, potentially without clinical oversight. | A crucial part of monitoring the holistic effects of hormonal optimization, discussed in confidence with a provider to make necessary adjustments to therapy. |

The fundamental difference is one of purpose. In the clinical world, your data serves a singular purpose ∞ your health and well-being. Its collection, analysis, and storage are all optimized to support that goal within a legally protected framework.

In the commercial app world, your data often serves a dual purpose ∞ to provide a service to you, and to generate value for the company and its partners. This dual purpose creates an inherent conflict of interest that does not exist in the same way within the sanctum of your doctor’s office. This reality requires a higher level of personal vigilance and a deeper understanding of the digital spaces where we choose to share the story of our health.

References

- Dickinson Wright. “App Users Beware ∞ Most Healthcare, Fitness Tracker, and Wellness Apps Are Not Covered by HIPAA and HHS’s New FAQs Makes that Clear.” JD Supra, 13 July 2021.

- Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, LLP. “Risky Business? Sharing Data With Entities Not Covered by HIPAA.” 14 March 2019.

- IS Partners, LLC. “Data Privacy at Risk with Health and Wellness Apps.” 4 April 2023.

- HIPAA Journal. “Majority of Americans Mistakenly Believe Health App Data is Covered by HIPAA.” 26 July 2023.

- Caruso Law PLLC. “HIPAA ∞ Essential Information for Digital Health App Companies.” 3 March 2025.

- Federal Trade Commission. “Complying with FTC’s Health Breach Notification Rule.” July 2024.

- Davis Wright Tremaine. “FTC Finalizes Expansion of Health Breach Notification Rule’s Broad Applicability to Unauthorized App Disclosures.” 1 May 2024.

- Healthcare Dive. “FTC broadens health breach notification rule to include apps.” 29 April 2024.

- Fierce Healthcare. “FTC finalizes changes to data privacy rule to step up scrutiny of digital health apps.” 26 April 2024.

- eHealth Initiative. “Risky Business? Sharing Data with Entities Not Covered by HIPAA.” March 2019.

Reflection

The knowledge of these distinct data worlds is not meant to induce fear, but to instill a sense of deliberate action. Your health journey is yours to direct, and the information that chronicles that journey is a powerful asset. You are the ultimate custodian of this data.

The choice is not necessarily to disengage from useful technology, but to engage with a higher level of awareness. Every time you consider using a new digital health tool, you now have a framework for evaluation. You can begin to ask more pointed questions. Who is holding my data? What is their primary purpose? What are my rights if that data is shared?

This understanding transforms you from a passive user into an active, informed participant in your own health ecosystem. The path to optimizing your biological function, whether through nutritional changes, metabolic recalibration, or sophisticated hormonal protocols, begins with a foundation of high-integrity information.

This includes not only the data itself but also the security and sanctity of the container it is held in. Your personal health narrative is one of your most valuable possessions. The next step is to consider how you choose to protect it, who you entrust it to, and how you can leverage it to build the most vital, functional version of yourself.

Glossary

health information

health insurance

hipaa

protected health information

covered entities

covered entity

federal trade commission

health plans

wellness app

business associate

health breach notification rule

health and wellness apps

individually identifiable health information

their business associates

identifiable health information

personal health

data security

health data

data with third parties

wellness apps

re-identification

data provenance