Fundamentals

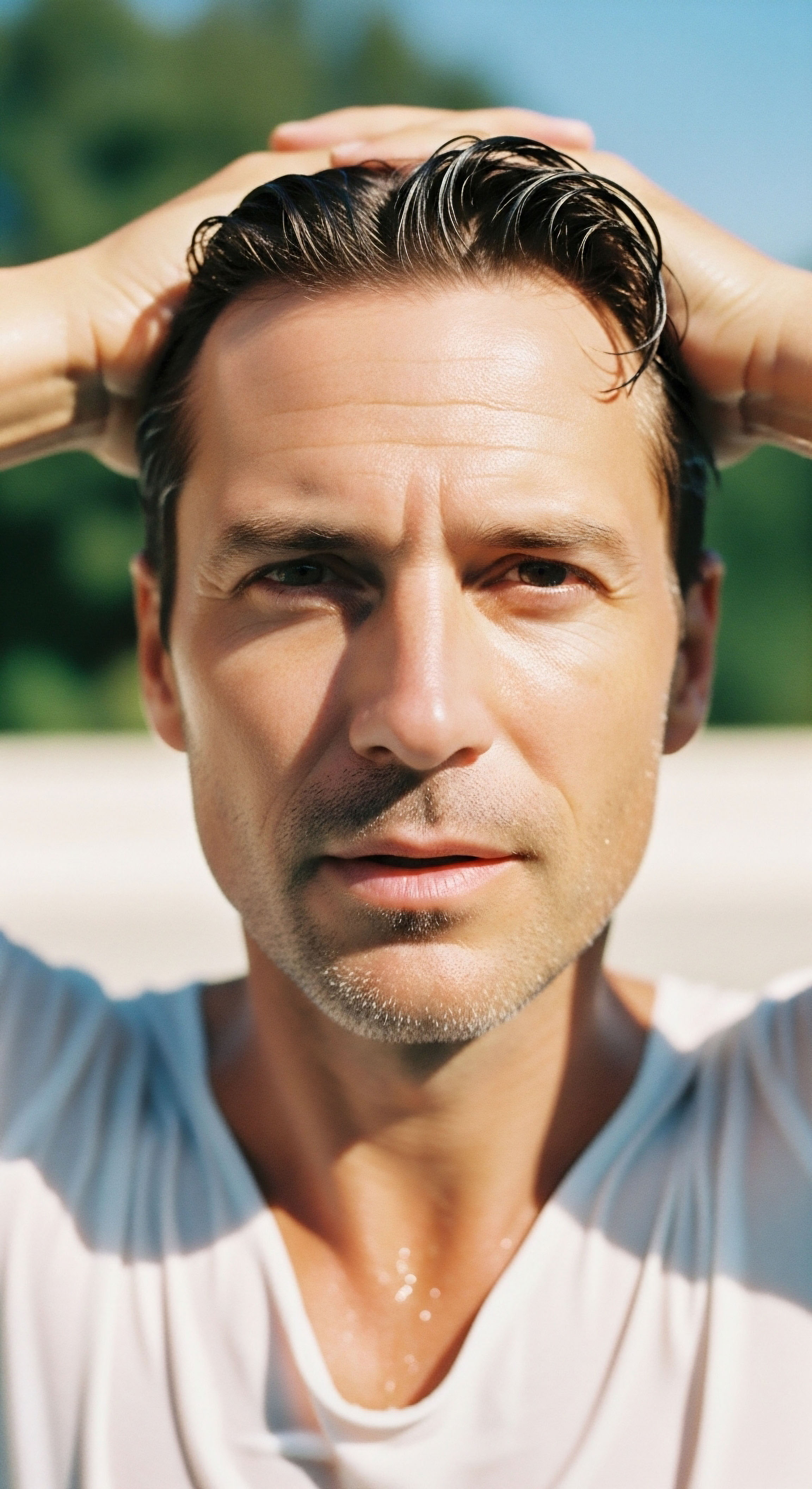

Have you ever experienced a subtle shift in your physical being, a quiet concern about changes that seem to whisper of deeper alterations within your body’s intricate systems? Perhaps a sense of diminished vitality, a feeling that your body’s internal rhythms are no longer quite in sync.

For many, this sensation can manifest as a concern about hormonal balance, particularly as it relates to male physiological function and reproductive health. Understanding these shifts, and the biological underpinnings that drive them, represents a significant step toward reclaiming a sense of well-being and robust function. This journey of comprehension begins with the body’s central command center for reproductive and hormonal regulation.

At the core of male endocrine health lies the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, often abbreviated as the HPG axis. Imagine this axis as a sophisticated communication network, a finely tuned orchestra where each section plays a vital role in maintaining hormonal equilibrium.

The conductor of this orchestra is the hypothalamus, a small but mighty region of the brain. It initiates the hormonal cascade by releasing a signaling molecule known as gonadotropin-releasing hormone, or GnRH. This release occurs in precise, rhythmic pulses, a critical aspect for proper function.

Upon receiving the GnRH signal, the pituitary gland, situated just beneath the brain, responds by secreting two essential hormones into the bloodstream ∞ luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). LH travels to the testes, specifically targeting the Leydig cells, which are responsible for producing testosterone.

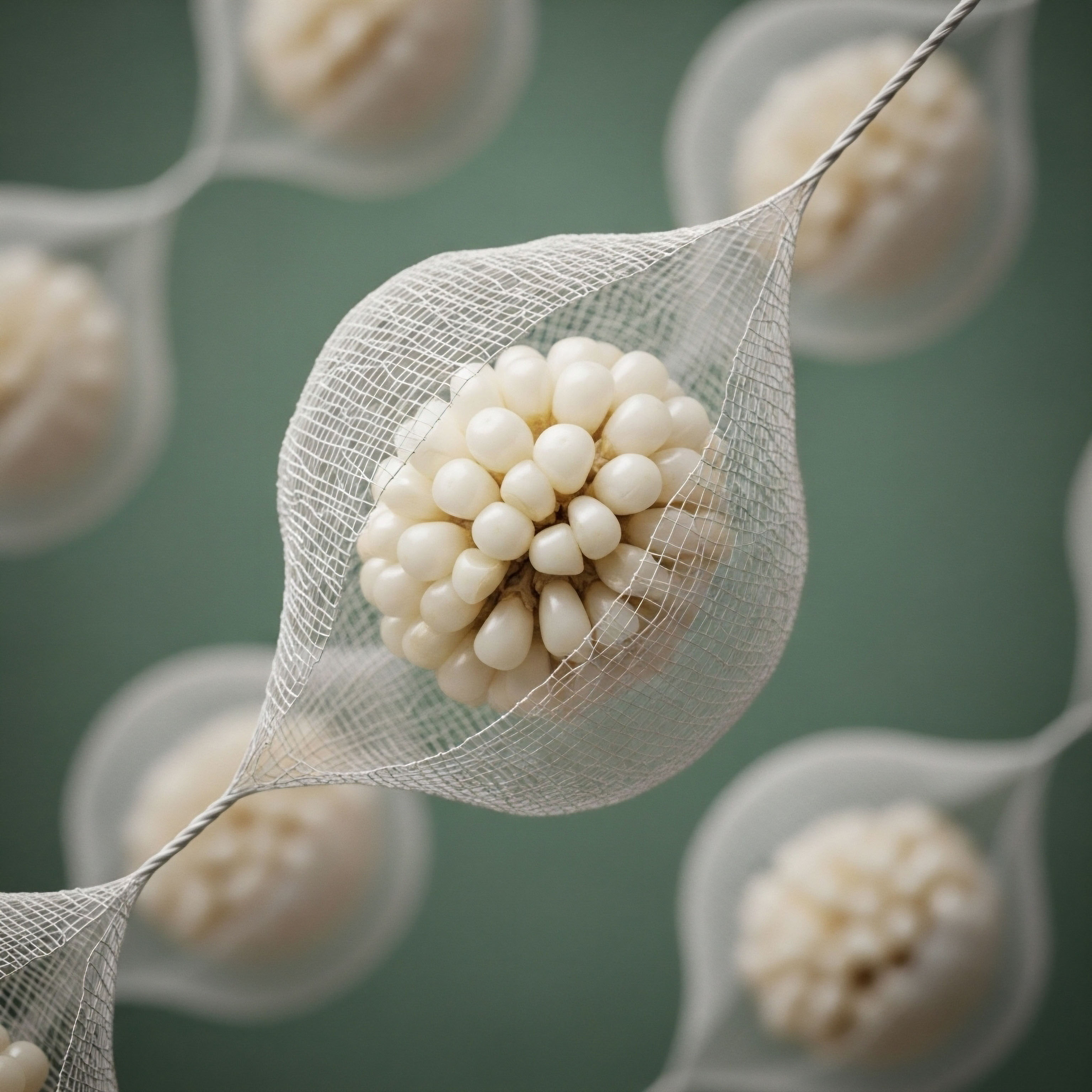

FSH, on the other hand, acts on the Sertoli cells within the testes, playing a direct role in supporting spermatogenesis, the process of sperm creation. This coordinated action ensures the production of both testosterone and viable sperm, vital for overall male health and reproductive capacity.

When exogenous testosterone, such as that used in testosterone replacement therapy (TRT), is introduced into the body, the HPG axis perceives elevated testosterone levels. This triggers a natural feedback loop, signaling the hypothalamus and pituitary to reduce their own production of GnRH, LH, and FSH.

This suppression, while a normal physiological response, can lead to a reduction in natural testosterone production by the testes and, significantly, a decline in sperm production. It can also result in a decrease in testicular size, a phenomenon known as testicular atrophy. For individuals embarking on a path of hormonal optimization, particularly those considering or undergoing TRT, addressing these potential consequences becomes a central consideration.

Understanding the HPG axis is the first step in comprehending how external hormonal interventions influence the body’s natural balance.

The conversation around maintaining testicular function and fertility during or after TRT often involves two key agents ∞ Gonadorelin and Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (HCG). While both are employed to support testicular recovery, their mechanisms of action within the HPG axis differ fundamentally.

Gonadorelin directly stimulates the pituitary gland, mimicking the brain’s natural GnRH pulses, thereby encouraging the pituitary to produce its own LH and FSH. HCG, conversely, acts as a direct analog of LH, bypassing the pituitary and directly stimulating the Leydig cells in the testes. This distinction in their operational pathways shapes their clinical application and the physiological responses they elicit, offering different avenues for supporting male reproductive health.

Intermediate

Navigating the landscape of hormonal optimization requires a precise understanding of how various agents interact with the body’s intricate signaling systems. When considering testicular recovery, particularly in the context of exogenous testosterone administration, the choice between Gonadorelin and HCG hinges on their distinct biological actions and the specific goals of the individual. Both compounds serve to mitigate the suppressive effects of external testosterone on the HPG axis, yet they achieve this through different points of intervention within the endocrine hierarchy.

How Gonadorelin Works in the Endocrine System

Gonadorelin is a synthetic decapeptide, structurally identical to the natural gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) produced by the hypothalamus. Its therapeutic utility stems from its ability to replicate the pulsatile release pattern of endogenous GnRH. When administered, Gonadorelin binds to specific GnRH receptors on the gonadotrope cells of the anterior pituitary gland.

This binding initiates a complex intracellular signaling cascade, primarily involving the phospholipase C pathway, which ultimately triggers the synthesis and release of both luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) from the pituitary.

The subsequent release of LH and FSH then acts downstream on the testes. LH stimulates the Leydig cells to produce testosterone, while FSH supports the Sertoli cells in the process of spermatogenesis. This indirect stimulation of testicular function, by reactivating the pituitary’s role in the HPG axis, helps to maintain the testes’ natural capacity for hormone and sperm production.

Gonadorelin’s mechanism is akin to sending a clear, rhythmic signal to the pituitary, prompting it to resume its orchestrating role in the hormonal symphony. This approach aims to preserve the integrity of the entire HPG axis, rather than bypassing a segment of it.

How HCG Influences Testicular Function

Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (HCG), in contrast, operates through a different pathway. HCG is a glycoprotein hormone, naturally produced during pregnancy, but its structure closely resembles that of luteinizing hormone (LH). Because of this structural similarity, HCG acts as an LH analog. It directly binds to the LH receptors on the Leydig cells within the testes. This direct stimulation prompts the Leydig cells to produce testosterone, effectively bypassing the pituitary gland’s role in the HPG axis.

The primary benefit of HCG in the context of testosterone replacement therapy is its ability to maintain intratesticular testosterone levels. Exogenous testosterone suppresses the pituitary’s release of LH, which would normally lead to a significant drop in testicular testosterone and, consequently, testicular atrophy and impaired spermatogenesis.

By mimicking LH, HCG ensures that the Leydig cells continue to receive the necessary signal to produce testosterone locally within the testes, thereby preserving testicular size and supporting sperm production. While HCG primarily mimics LH, some research suggests it may possess a minor degree of FSH-like activity, though its main impact remains on Leydig cell stimulation.

Gonadorelin stimulates the pituitary to produce LH and FSH, while HCG directly stimulates the testes by mimicking LH.

Comparing Administration and Efficacy

The practical application of Gonadorelin and HCG also presents notable differences, particularly concerning their administration frequency and perceived efficacy in clinical settings. Gonadorelin, to effectively mimic the natural pulsatile release of GnRH, often requires more frequent administration. Clinical studies investigating its use for fertility restoration have employed pulsatile pumps delivering microdoses every 90 minutes, or daily subcutaneous injections. This frequent dosing schedule aims to maintain a consistent, physiological signaling pattern to the pituitary.

HCG, possessing a longer half-life than natural LH, typically allows for less frequent injections, commonly administered two to three times per week subcutaneously. This convenience has historically made HCG a preferred choice for many individuals undergoing TRT who wish to maintain testicular function. However, recent regulatory changes have impacted the availability of compounded HCG, leading some clinics to transition towards Gonadorelin as an alternative.

Clinical outcomes comparing the two agents for testicular recovery and fertility preservation during TRT show varying results. Some studies indicate that pulsatile Gonadorelin therapy may induce earlier onset of spermatogenesis compared to cyclical gonadotropin therapy (HCG with human menopausal gonadotropin, HMG).

However, the overall rates of inducing spermatogenesis may not differ significantly between the two approaches over a longer period. Some clinical experiences suggest HCG might be superior for reversing testicular atrophy and resolving associated symptoms, while Gonadorelin may lead to less estrogen conversion directly from the testes.

Key Differences in Testicular Recovery Agents

| Characteristic | Gonadorelin | Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (HCG) |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action | Mimics hypothalamic GnRH, stimulating pituitary LH and FSH release. | Mimics pituitary LH, directly stimulating Leydig cells in testes. |

| Target Organ | Anterior Pituitary Gland | Testes (Leydig Cells) |

| Hormones Stimulated | LH and FSH | Primarily Testosterone (via LH receptor activation) |

| Impact on HPG Axis | Reactivates the entire axis, promoting endogenous signaling. | Bypasses pituitary, directly stimulating gonadal function. |

| Typical Administration Frequency | Daily or pulsatile (e.g. every 90 minutes via pump) | Two to three times per week |

| Potential Estrogen Conversion | Generally lower direct testicular estrogen stimulation. | Can lead to higher estrogen levels due to direct testicular stimulation. |

| Primary Use in TRT | Maintain testicular size, function, and fertility by supporting natural LH/FSH. | Prevent testicular atrophy, preserve intratesticular testosterone and spermatogenesis. |

Considering Post-TRT Recovery Protocols

For individuals who discontinue testosterone replacement therapy, or those seeking to optimize fertility while on TRT, specific protocols are often implemented to encourage the natural recovery of endogenous hormone production and spermatogenesis. This is where agents like Gonadorelin and HCG play a significant role. The goal is to “recalibrate” the HPG axis, encouraging the body to resume its own production of testosterone and sperm.

In a post-TRT scenario, the HPG axis is typically suppressed. Gonadorelin, by providing a pulsatile GnRH signal, can help to “wake up” the pituitary gland, prompting it to restart LH and FSH secretion. This can be a more physiological approach to recovery, as it aims to restore the natural signaling pathway from the brain down to the testes.

The inclusion of other medications, such as Tamoxifen or Clomid (Enclomiphene), which act as selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), can further support this process by blocking estrogen’s negative feedback on the hypothalamus and pituitary, thereby increasing endogenous LH and FSH release.

HCG can also be used in post-TRT recovery, particularly to stimulate Leydig cell function and increase intratesticular testosterone. While it directly stimulates the testes, it does not directly address the pituitary’s suppressed state.

Often, a combination of agents is employed in these recovery protocols to address different aspects of HPG axis function and maximize the chances of restoring fertility and endogenous hormone production. The precise protocol is always tailored to the individual’s unique physiological response and their specific health objectives.

What Are the Practical Considerations for Administration?

The practical aspects of administering Gonadorelin and HCG differ, influencing patient preference and adherence. Gonadorelin, especially when aiming for a truly pulsatile delivery, might involve subcutaneous injections, sometimes requiring a pump for consistent micro-dosing throughout the day. This method, while mimicking natural physiology, can be more demanding for the individual. Simpler daily subcutaneous injections are also utilized, aiming to provide a consistent stimulus to the pituitary.

HCG is typically administered via subcutaneous injection two to three times per week. This less frequent dosing schedule often makes it a more convenient option for many individuals. The choice between these administration methods often balances the desire for physiological mimicry with the practicalities of daily life and individual comfort with injections. Both agents require careful monitoring of hormone levels to ensure optimal dosing and to mitigate potential side effects.

Academic

A deeper understanding of Gonadorelin and HCG necessitates an exploration into their molecular pharmacology, the nuances of their receptor interactions, and the comprehensive systems-biology implications of their administration. The endocrine system operates as a complex adaptive network, and interventions at one level invariably ripple through interconnected pathways. Analyzing these agents from an academic perspective reveals why their distinct mechanisms yield different clinical profiles, particularly concerning the delicate balance of testicular recovery and fertility preservation.

Molecular Pharmacology and Receptor Specificity

The fundamental difference between Gonadorelin and HCG lies in their specific receptor targets and the downstream signaling cascades they activate. Gonadorelin, as a synthetic GnRH, binds to the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor (GnRHR) located on the surface of gonadotrope cells in the anterior pituitary. This receptor is a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR).

Upon Gonadorelin binding, the GnRHR activates the phospholipase C pathway, leading to the production of inositol trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG). IP3 triggers the release of intracellular calcium ions, while DAG activates protein kinase C (PKC). This cascade culminates in the exocytosis of stored LH and FSH, and also stimulates the synthesis of new gonadotropin molecules.

The pulsatile nature of GnRH (and thus Gonadorelin) signaling is paramount; continuous, non-pulsatile administration can lead to GnRHR desensitization and suppression of gonadotropin release, a principle exploited in GnRH agonist therapies for prostate cancer.

HCG, conversely, exerts its effects by binding to the luteinizing hormone/choriogonadotropin receptor (LHCGR), primarily found on Leydig cells in the testes. The LHCGR is also a GPCR, but its activation by HCG (or endogenous LH) primarily stimulates the adenylyl cyclase pathway, leading to an increase in intracellular cyclic AMP (cAMP).

Elevated cAMP then activates protein kinase A (PKA), which phosphorylates key enzymes involved in cholesterol transport and steroidogenesis, ultimately boosting testosterone synthesis within the Leydig cells. The direct action of HCG on the testes means it bypasses the hypothalamic-pituitary axis entirely, providing a direct signal for testosterone production regardless of central suppression.

Gonadorelin activates pituitary GnRH receptors, prompting LH and FSH release, while HCG directly stimulates testicular LH receptors for testosterone production.

Clinical Efficacy and Spermatogenesis Outcomes

Clinical trials comparing Gonadorelin and HCG for the induction or maintenance of spermatogenesis, particularly in men with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (HH) or those undergoing TRT, offer valuable insights. A retrospective study by Huang et al. (2015) in China compared pulsatile Gonadorelin therapy (10 μg every 90 minutes) with cyclical gonadotropin therapy (HCG 3,000 IU plus HMG 75 IU twice weekly) in men with congenital HH.

The study reported that pulsatile Gonadorelin induced earlier spermatogenesis, with a median time of 6 months compared to 14 months for the HCG/HMG group. While the onset was earlier, the overall rates of successful spermatogenesis (90% for Gonadorelin, 83.3% for HCG/HMG) were not statistically different. This suggests that while both approaches can be effective, Gonadorelin may accelerate the process of sperm production in some cases.

The distinction in their effects on FSH is particularly relevant for spermatogenesis. Gonadorelin stimulates both LH and FSH release from the pituitary, providing a more complete physiological signal for both testosterone production and direct Sertoli cell support for sperm maturation. HCG, being primarily an LH analog, predominantly stimulates testosterone production.

While intratesticular testosterone is crucial for spermatogenesis, FSH also plays a direct role in Sertoli cell function and sperm development. Therefore, in some cases, HCG therapy for fertility may require the addition of exogenous FSH (e.g. human menopausal gonadotropin, HMG, or recombinant FSH) to achieve optimal spermatogenesis, especially in men who have never achieved it.

Comparative Efficacy in Testicular Recovery

The effectiveness of Gonadorelin and HCG in preventing or reversing testicular atrophy during TRT is a significant clinical consideration. Testicular atrophy, characterized by a reduction in testicular volume, is a common consequence of TRT due to the suppression of endogenous LH and FSH.

- Gonadorelin’s Role ∞ By stimulating the pituitary to release LH and FSH, Gonadorelin helps maintain the physiological signals necessary for testicular size and function. This indirect activation aims to keep the testes “active” and responsive, thereby mitigating atrophy.

- HCG’s Role ∞ HCG directly stimulates Leydig cells, maintaining intratesticular testosterone levels, which are critical for preserving testicular volume and spermatogenesis. Clinical experience and studies suggest HCG is highly effective in preventing testicular shrinkage.

- Comparative Outcomes ∞ While both agents aim to prevent atrophy, some clinical observations suggest HCG may be more consistently effective in reversing existing testicular shrinkage or preventing it during TRT. However, Gonadorelin’s ability to stimulate FSH may offer a more comprehensive approach to maintaining overall testicular health and spermatogenesis.

Metabolic and Endocrine Interplay

The impact of Gonadorelin and HCG extends beyond direct testicular function, influencing broader metabolic and endocrine parameters. The HPG axis is not an isolated system; it interacts extensively with other endocrine axes, such as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which governs the stress response. Chronic stress, for instance, can suppress GnRH release, thereby impacting reproductive function. Interventions that support the HPG axis, whether through Gonadorelin or HCG, can contribute to overall endocrine resilience.

A notable difference between the two agents lies in their potential influence on estrogen levels. HCG, by directly stimulating Leydig cells to produce testosterone, can lead to a more pronounced increase in estrogen (estradiol) due to the aromatization of testosterone within the testes and peripheral tissues.

This can necessitate the co-administration of an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole to manage estrogen levels and mitigate side effects such as gynecomastia or fluid retention. Gonadorelin, by stimulating the pituitary, tends to result in a more balanced increase in LH and FSH, and may lead to less direct testicular estrogen production compared to HCG, potentially reducing the need for aggressive estrogen management in some individuals.

The choice between Gonadorelin and HCG, therefore, involves a careful consideration of the individual’s overall hormonal profile, their specific goals (e.g. fertility vs. testicular size maintenance), and their tolerance for potential side effects. A personalized wellness protocol will account for these intricate interactions, aiming to restore not just isolated hormone levels, but a harmonious balance across the entire endocrine system.

The long-term implications of sustained HPG axis stimulation versus direct gonadal stimulation are areas of ongoing research, emphasizing the need for continued clinical monitoring and individualized therapeutic adjustments.

How Do Individual Responses Shape Treatment Protocols?

Individual physiological responses to Gonadorelin and HCG can vary significantly, underscoring the necessity of personalized treatment protocols. Genetic predispositions, baseline hormonal status, and the presence of underlying conditions all influence how an individual’s HPG axis responds to these interventions. For instance, men with primary hypogonadism, where the testes themselves are dysfunctional, may respond differently to HCG (which directly stimulates the testes) compared to those with secondary hypogonadism, where the issue lies with the hypothalamus or pituitary.

The concept of “receptor sensitivity” also plays a role. Over time, the pituitary’s sensitivity to Gonadorelin or the Leydig cells’ sensitivity to HCG might change, requiring dosage adjustments. This dynamic interplay necessitates regular monitoring of serum hormone levels, including testosterone, LH, FSH, and estradiol, to ensure the protocol remains optimized for the individual’s evolving needs. Such precise biochemical recalibration is a hallmark of advanced hormonal optimization.

What Are the Long-Term Implications of HPG Axis Modulation?

Considering the long-term implications of HPG axis modulation with Gonadorelin or HCG is paramount for comprehensive wellness planning. Sustained exogenous stimulation, whether direct or indirect, can influence the natural feedback mechanisms of the endocrine system. While these therapies are designed to mitigate the suppressive effects of TRT, the goal is always to achieve a state of physiological balance that supports overall health and longevity.

Research continues to refine our understanding of how these interventions affect testicular health, sperm quality, and the broader metabolic profile over extended periods. The objective is not merely to address a symptom but to support the body’s innate capacity for function and vitality. This involves a continuous dialogue between clinical data, subjective experience, and the evolving scientific understanding of human physiology.

References

- Blumenfeld, Z. (2021). Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonists and Antagonists ∞ Clinical Applications. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine, 39(03), 195-204.

- Finkelstein, J. S. Yu, E. W. & Burnett-Bowie, S. A. (2013). Gonadotropin-releasing hormone and human chorionic gonadotropin in the management of male hypogonadism. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 98(7), 2747-2755.

- Hall, J. E. & Guyton, A. C. (2020). Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology (14th ed.). Elsevier.

- Huang, X. et al. (2015). The Pulsatile Gonadorelin Pump Induces Earlier Spermatogenesis Than Cyclical Gonadotropin Therapy in Congenital Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism Men. American Journal of Men’s Health, 9(6), 493-500.

- Klein, C. E. (2005). The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis. In V. T. DeVita Jr. S. Hellman, & S. A. Rosenberg (Eds.), Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine (7th ed.). BC Decker.

- Lipshultz, L. I. & Pastuszak, A. W. (2018). Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) in the Management of Male Infertility. Current Opinion in Urology, 28(6), 569-575.

- Pearlman, A. (2018). Fertility Preservation in Men on Testosterone Replacement Therapy. Urology Practice, 5(6), 460-466.

- Swerdloff, R. S. & Wang, C. (2018). Gonadotropins and Their Analogs ∞ Current and Potential Clinical Applications. Endocrine Reviews, 39(6), 911-937.

Reflection

As we conclude this exploration into the distinct mechanisms of Gonadorelin and HCG for testicular recovery, consider the profound implications for your own health journey. The knowledge shared here is not merely a collection of facts; it represents a deeper understanding of the biological systems that shape your vitality and function. Recognizing the intricate dance of the HPG axis and how targeted interventions can support its balance offers a powerful perspective.

This information serves as a foundation, a starting point for a more informed dialogue with your healthcare provider. Your unique biological blueprint and personal health aspirations will always guide the most appropriate path forward. Understanding these complex processes allows you to engage proactively in decisions about your well-being, moving beyond passive acceptance to active participation in optimizing your health.

The path to reclaiming vitality is deeply personal, requiring both scientific insight and an empathetic appreciation for your lived experience. This journey is about empowering yourself with knowledge, translating complex clinical science into actionable wisdom that allows you to pursue a life of robust health and uncompromised function.