Fundamentals

The moment hormonal therapy concludes marks a profound transition within your body’s internal landscape. A system that had grown accustomed to external support must now re-engage its own intricate production lines. You may feel a sense of uncertainty, a questioning of your body’s capacity to resume its natural rhythm.

This experience is a valid and understandable starting point for a new phase of personal wellness. The path forward involves understanding and actively participating in the recalibration of your endocrine system. Physical movement, tailored with intention, becomes a primary form of communication with your body, guiding it back toward self-sufficiency.

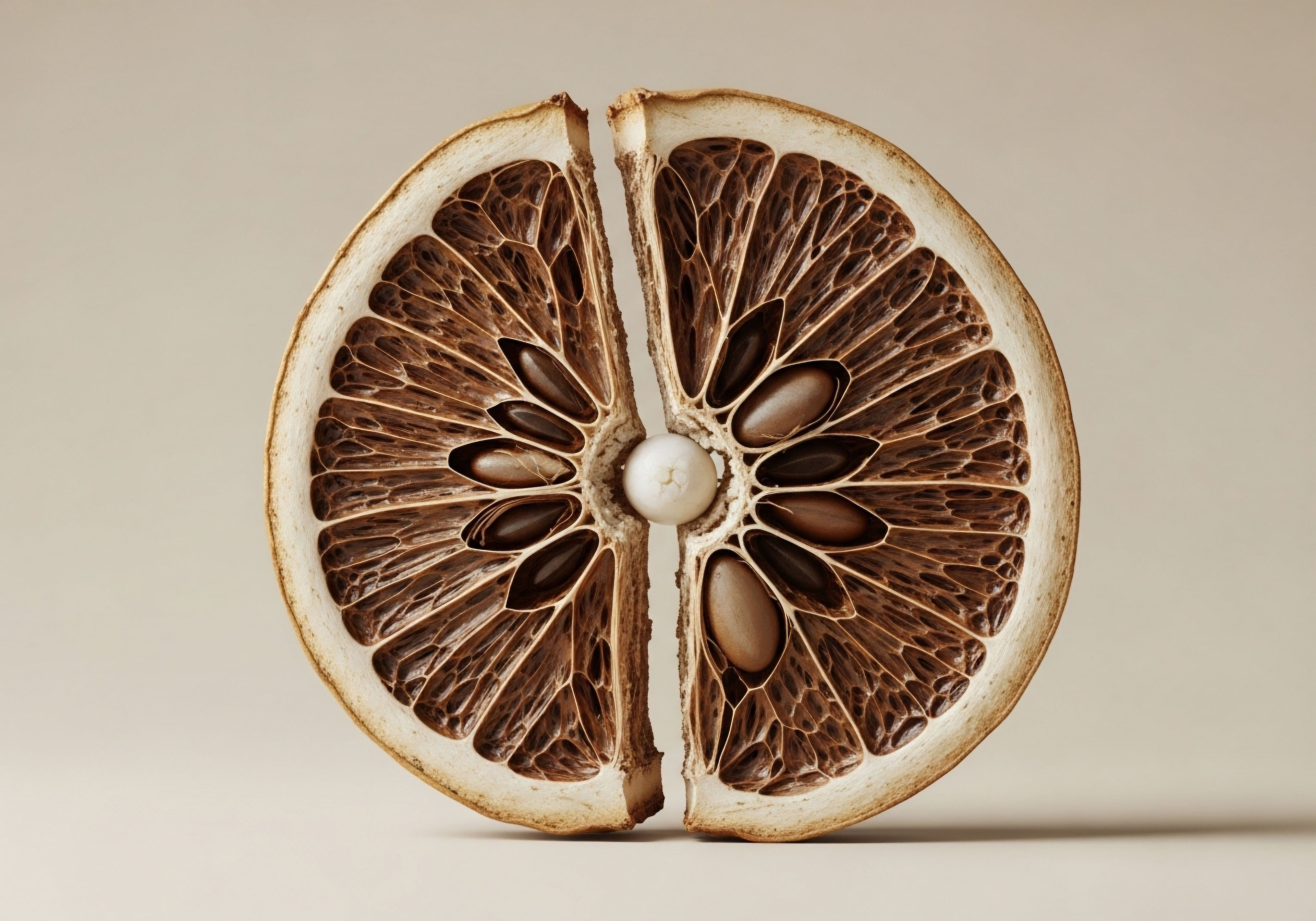

At the center of this recalibration is the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. This is the master regulatory circuit governing your reproductive and hormonal health. Think of it as a sophisticated internal thermostat. The hypothalamus, located in the brain, senses the body’s needs and sends a signal ∞ Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) ∞ to the pituitary gland.

The pituitary, in turn, releases Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) into the bloodstream. These hormones travel to the gonads (testes in men, ovaries in women), instructing them to produce testosterone and other essential sex hormones. When therapy provides hormones from an external source, this entire axis quiets down. Post-therapy, the goal is to gently and consistently encourage this dormant system to awaken and resume its vital conversation.

Exercise acts as a potent biological stimulus, prompting the body’s hormonal systems to adapt and re-establish their natural production cycles.

How Does Your Body Relearn to Make Hormones?

Your body relearns its hormonal cadence through a process of demand and response. Exercise, particularly structured physical stress, creates a clear and powerful demand. When you engage in strenuous activity, you are sending a system-wide signal that the body requires strength, repair, and energy.

This signal travels up the chain of command, beginning a cascade of physiological events. The endocrine system responds to this demand by modulating the release of key hormones to manage the stress and initiate recovery and adaptation.

The primary hormones involved in this adaptive response include:

- Testosterone ∞ A central hormone for both men and women, it is integral to muscle repair, bone density, and metabolic regulation. Resistance training, in particular, creates a powerful stimulus for its release.

- Growth Hormone (GH) ∞ Released by the pituitary gland, GH works to stimulate cellular repair and regeneration, particularly in muscle and connective tissues, following the micro-trauma induced by exercise.

- Cortisol ∞ Often associated with stress, cortisol plays a necessary role during exercise by mobilizing energy stores. The pattern of its release and decline ∞ a sharp peak during activity followed by a rapid fall ∞ is the hallmark of a healthy, resilient stress response system. Chronic elevation, conversely, can suppress the HPG axis.

- Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1) ∞ Working in concert with GH, IGF-1 is a powerful mediator of the anabolic, or tissue-building, processes that follow a workout.

Engaging in consistent physical activity encourages the HPG axis to become more sensitive and responsive. Each workout serves as a practice run, refining the signaling pathways and improving the efficiency of hormone production and utilization. This is the foundational principle of using exercise as a tool to support your body’s return to endogenous hormonal autonomy.

Intermediate

Transitioning from foundational concepts to practical application requires a more detailed examination of how specific exercise modalities interact with a post-therapy hormonal environment. For individuals discontinuing Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) or other hormonal support, the body’s internal signaling has been suppressed.

A post-therapy protocol, often including agents like Gonadorelin, Clomid, or Tamoxifen, is designed to re-stimulate the HPG axis. Gonadorelin acts as a direct signal to the pituitary, mimicking GnRH to prompt LH and FSH release. Clomid and Tamoxifen work by blocking estrogen receptors in the hypothalamus, which tricks the brain into perceiving a low-estrogen state and, in response, increasing its output of GnRH. Exercise becomes a powerful synergistic tool that amplifies the effects of these protocols.

The physical stress of a structured workout enhances the body’s sensitivity to these signals. When you perform resistance training, for instance, you are creating a physiological environment that demands anabolic support for muscle repair. This demand potentiates the action of the newly stimulated LH pulse, encouraging the gonads to respond more robustly. The choice of exercise modality is therefore a strategic decision, tailored to achieve specific hormonal and metabolic outcomes.

Which Exercise Type Best Supports Your Hormonal Goals?

Different forms of exercise send distinct signals to the endocrine system. A comprehensive plan often incorporates several modalities to create a balanced and robust stimulus for hormonal recalibration. The key is to understand what each type of training prioritizes and how that aligns with your body’s needs after therapy.

Resistance Training the Anabolic Foundation

Lifting weights is a cornerstone of post-therapy recovery. It focuses on compound movements that recruit large muscle groups, such as squats, deadlifts, presses, and rows. This type of stimulus is uniquely effective at promoting a favorable hormonal cascade. The immediate response includes a significant, albeit transient, increase in testosterone and growth hormone.

This acute spike helps to saturate muscle tissue with anabolic signals at a critical moment. Over the long term, consistent resistance training improves insulin sensitivity and increases the density of androgen receptors in muscle cells, making your body more efficient at using the testosterone it produces.

A well-structured exercise program strategically combines different training styles to balance anabolic signals, metabolic health, and stress management for optimal hormonal recovery.

High-Intensity Interval Training the Metabolic Accelerator

High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) involves short bursts of maximum-effort work followed by brief recovery periods. This modality is exceptionally efficient at improving metabolic health. It has been shown to be highly effective at increasing mitochondrial density and improving insulin sensitivity, which is a foundational element of proper endocrine function.

From a hormonal perspective, HIIT can trigger a significant growth hormone release and can be a potent stimulus for testosterone production, similar to resistance training. Its primary advantage is time efficiency and its powerful impact on cardiovascular and metabolic conditioning, which are closely linked to hormonal balance.

Aerobic Exercise the System Regulator

Steady-state cardiovascular exercise, performed at a moderate intensity for a longer duration, plays a distinct and vital role. While it does not typically induce the same large anabolic hormone spikes as resistance training or HIIT, its benefits are systemic and profound.

Consistent aerobic exercise is instrumental in managing stress by regulating the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, ensuring cortisol is released and cleared efficiently. It also has a significant impact on Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG). SHBG binds to testosterone in the bloodstream, making it unavailable to tissues.

Intense, long-duration endurance training can sometimes increase SHBG, which might be counterproductive. However, moderate aerobic exercise as part of a balanced program helps maintain healthy SHBG levels, ensuring a greater proportion of free, bioavailable testosterone.

The following table compares the typical hormonal responses elicited by these primary exercise modalities.

| Hormone/Factor | Resistance Training | High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) | Moderate Aerobic Exercise |

|---|---|---|---|

| Testosterone (Acute) |

Significant Increase |

Moderate to Significant Increase |

Minimal to Moderate Increase |

| Growth Hormone (GH) |

Significant Increase |

Significant Increase |

Moderate Increase |

| Cortisol |

Acute Increase, Rapid Decline |

Acute Increase, Rapid Decline |

Modest Increase, Regulates Baseline |

| Insulin Sensitivity |

Improved |

Significantly Improved |

Improved |

| SHBG |

Generally Stable or Decreased |

Generally Stable |

Can Increase with Very High Volume |

Academic

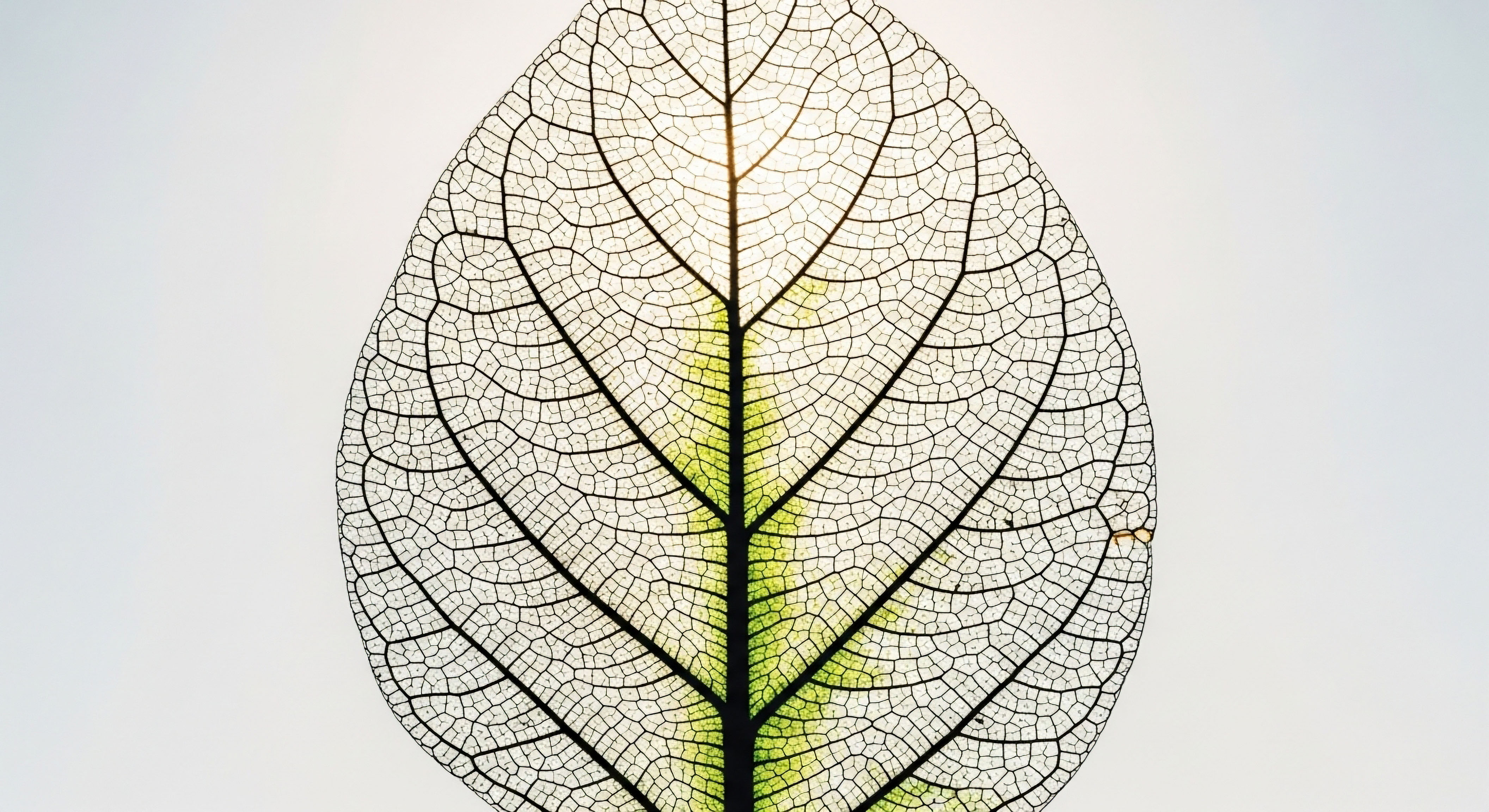

A sophisticated analysis of exercise’s influence on endogenous hormone production moves beyond measuring transient changes in circulating hormone levels. The academic perspective focuses on the intricate molecular signaling that occurs within the target tissues themselves, particularly skeletal muscle.

The prevailing evidence indicates that the acute, systemic hormonal surge post-exercise is an associated phenomenon rather than the primary driver of muscle hypertrophy and adaptation. The true locus of control resides in local, or autocrine and paracrine, signaling pathways activated by the mechanical stress of muscle contraction.

This understanding reframes the role of exercise in a post-therapy context. It is a process of re-educating the muscle tissue to become more sensitive and responsive to the hormonal signals that a recovering HPG axis will produce.

Mechanical loading of muscle fibers during resistance exercise initiates a process called mechanotransduction. This is the conversion of physical force into a cascade of biochemical signals. This process activates key regulatory pathways like the mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway, which is a central controller of protein synthesis and cell growth.

Simultaneously, it influences the local expression of growth factors and the sensitivity of androgen receptors within the muscle cell. In essence, exercise prepares the muscle to listen more intently to the hormonal messages circulating in the blood. Therefore, even a modest recovery in endogenous testosterone production can have a significant physiological impact when paired with a consistent training stimulus that upregulates local receptor density and sensitivity.

Does the Post-Workout Hormone Spike Truly Matter?

The question of the significance of the post-exercise anabolic hormone spike has been a subject of considerable scientific investigation. Studies that have experimentally blunted this systemic hormonal response have found that it does not eliminate the hypertrophic gains from resistance training.

This suggests the systemic spike is a downstream effect, while the foundational anabolic signaling is local to the worked muscle. This has profound implications for an individual recalibrating their endocrine system. The focus shifts from chasing a temporary hormonal peak to creating a sustained state of enhanced local sensitivity.

The interplay between the HPG axis and the HPA (adrenal) axis is also critically important. Intense exercise is a stressor that activates both systems. The cortisol released from the adrenal glands is catabolic in nature, and chronically high levels can suppress gonadal function.

However, the acute cortisol pulse during a workout is a necessary part of the adaptive process. A well-trained individual exhibits a rapid cortisol rise during exercise followed by a swift decline, a pattern indicative of a resilient and efficient stress response system.

An improperly managed training program, with excessive volume or inadequate recovery, can lead to a chronically elevated cortisol environment, which would directly antagonize the goal of restarting the HPG axis. This highlights the importance of periodization and recovery management in any post-therapy exercise protocol.

The true power of exercise lies in its ability to enhance the sensitivity of local tissues to hormones, making the body more efficient at using what it produces.

The following table outlines key molecular pathways and their relationship to different exercise stimuli, providing a deeper view of the underlying biology.

| Pathway / Factor | Primary Stimulus | Biological Function in Post-Therapy Context |

|---|---|---|

| mTORC1 Pathway |

Resistance Training, Amino Acids |

Acts as the master regulator of muscle protein synthesis. Its activation is essential for translating the hormonal signal into tangible tissue growth and repair. |

| AMPK Pathway |

Endurance Exercise, HIIT |

Senses cellular energy status. It enhances insulin sensitivity and mitochondrial biogenesis, improving the metabolic foundation upon which hormonal health is built. |

| Androgen Receptor (AR) Density |

Resistance Training |

Increases the number of “docking stations” for testosterone within muscle cells. This amplifies the effect of even modest levels of endogenous testosterone. |

| Local IGF-1 (Mechano-Growth Factor) |

Mechanical Stretch/Load |

A splice variant of IGF-1 produced directly within the muscle in response to load. It initiates the satellite cell activation necessary for muscle repair and hypertrophy, independent of systemic GH/IGF-1 levels. |

Monitoring progress during this phase should involve tracking specific biomarkers beyond just total testosterone. A comprehensive panel provides a more complete picture of the HPG axis function and overall metabolic health.

- Luteinizing Hormone (LH) ∞ A direct indicator of pituitary output and the primary signal to the gonads. Seeing LH rise into the normal range is a key sign of HPG axis recovery.

- Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) ∞ Tracking this protein is essential for understanding free, bioavailable testosterone. Exercise and diet can modulate its levels.

- Estradiol (E2) ∞ This estrogen is crucial for male and female health. Its balance with testosterone is vital, and exercise can influence the activity of the aromatase enzyme that converts testosterone to estradiol.

- Fasting Insulin and Glucose ∞ These markers reflect metabolic health, which is a direct upstream regulator of endocrine function. Improvements here, often driven by exercise, are a positive sign.

References

- Morton, Robert W. et al. “Neither load nor systemic hormones determine resistance training-mediated hypertrophy or strength gains in resistance-trained young men.” Journal of Applied Physiology 121.1 (2016) ∞ 129-138.

- Kraemer, William J. and Nicholas A. Ratamess. “Hormonal responses and adaptations to resistance exercise and training.” Sports medicine 35.4 (2005) ∞ 339-361.

- Hawkins, V. N. et al. “Effect of exercise on serum sex hormones in men ∞ a 12-month randomized clinical trial.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 40.2 (2008) ∞ 223.

- Di Luigi, L. et al. “Physical activity and neuroendocrine system.” Medicina Dello Sport 64.3 (2011) ∞ 335-49.

- Pilco, P. et al. “Effects of a 12-week resistance training program on the body composition and lipid profile in sedentary women.” Journal of Exercise Physiology Online 20.6 (2017).

- Vingren, J. L. et al. “Testosterone physiology in resistance exercise and training ∞ the up-stream regulatory elements.” Sports Medicine 40.12 (2010) ∞ 1037-1053.

- Enea, C. et al. “The effect of a 12-week training programme on body composition and hormone levels in adolescent girls.” Journal of sports sciences 27.11 (2009) ∞ 1167-1175.

- Sgrò, P. et al. “Anabolic-androgenic steroids and brain reward.” Current neuropharmacology 16.8 (2018) ∞ 1099-1113.

Reflection

Charting Your Personal Recovery

The information presented here provides a map of the biological territory you are navigating. It details the signals, the pathways, and the systems involved in reclaiming your body’s innate hormonal vitality. This knowledge is the essential first component. It transforms abstract feelings of uncertainty into a clear understanding of the physiological processes at play.

Your body is not a machine with a broken part; it is a dynamic, adaptive system that has been temporarily quieted and is waiting for the right signals to reawaken.

Consider your exercise regimen as a form of dialogue. Each session of lifting, each interval of intensity, and each moment of mindful movement is a message sent to your endocrine system. You are providing the stimulus, the raw material for adaptation. The true journey begins as you learn to listen to your body’s response.

It speaks in the language of energy levels, sleep quality, mental clarity, and physical strength. This process of intentional action and careful observation is the foundation of a personalized path to wellness, one that is guided by science and shaped by your own lived experience.

Glossary

endocrine system

resistance training

growth hormone

hpg axis

post-therapy protocol

insulin sensitivity

high-intensity interval training

metabolic health

metabolic conditioning

sex hormone-binding globulin

aerobic exercise

mechanotransduction