Fundamentals

The sensation can be one of profound internal dissonance. One day, your body operates with a predictable rhythm, and the next, its internal clock seems to have skipped ahead decades. This experience, a sudden and premature shift in your biological landscape, is a reality for women who enter menopause earlier than expected.

This is not about the number of candles on a cake; it is about a fundamental change in your body’s operating system, a change that originates with the cessation of ovarian function and radiates outward to affect every aspect of your metabolic health. Understanding this process is the first step toward reclaiming a sense of control and partnership with your own physiology.

Your body is a marvel of communication, a vast network where messages are sent and received every second of every day. Hormones are these messages, precise chemical signals that instruct your cells, tissues, and organs on how to function. Among the most influential of these signals for a woman’s body is estradiol, the primary estrogen produced by the ovaries.

Estradiol is a master regulator, a conductor ensuring that the intricate symphony of your metabolism plays in tune. It directs how your body uses and stores energy, how it manages blood sugar, and how it maintains the health of your blood vessels. Early menopause, clinically defined as the cessation of ovarian function before the age of 45, represents the abrupt silencing of this conductor.

The Core Metabolic Re-Routing

When the ovaries cease producing estradiol years or even decades ahead of the typical timeline, the body’s metabolic instructions undergo a significant rewrite. The systems that once relied on estrogen’s guidance must now function without it, leading to a cascade of predictable, and manageable, changes. This recalibration affects three primary areas of metabolic function, altering the very foundation of your physical well-being.

A Shift in Body Composition

One of the most immediate and tangible changes involves where and how your body stores fat. Estradiol actively directs fat to be stored in the hips, thighs, and buttocks ∞ the subcutaneous fat depots. This placement is metabolically safer. With the loss of estradiol, the body’s fat storage instructions change.

The new directive is to store fat centrally, deep within the abdominal cavity around your organs. This is known as visceral adipose tissue (VAT). This type of fat is a metabolically active organ in its own right, and its accumulation is a central feature of the metabolic disturbances that follow.

The loss of estrogen fundamentally alters the body’s fat distribution blueprint, favoring the accumulation of metabolically disruptive visceral fat.

Recalibrating the Body’s Fuel System

The way your body manages sugar, its primary fuel source, is also profoundly influenced by estradiol. Estrogen enhances your cells’ sensitivity to insulin, the hormone responsible for escorting glucose from your bloodstream into your cells to be used for energy. When estradiol levels decline, cells in your muscles and liver become less responsive to insulin’s signal.

This phenomenon is called insulin resistance. The result is that more insulin is required to do the same job, and blood sugar levels can remain elevated. This places a significant strain on your metabolic machinery, forming the basis for a host of downstream health concerns.

The Reorganization of Blood Lipids

Your cardiovascular system relies on a delicate balance of fats, or lipids, in the bloodstream. Estradiol helps maintain a favorable lipid profile, promoting higher levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL), the “good” cholesterol that helps clear plaque from arteries, and lower levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL), the “bad” cholesterol.

The hormonal shift of early menopause rewires this system. The result is often a rise in triglycerides and LDL cholesterol, coupled with a fall in protective HDL cholesterol. This specific combination, known as atherogenic dyslipidemia, creates conditions that are more conducive to the development of cardiovascular issues over time.

- Visceral Adipose Tissue (VAT) ∞ This is not the fat you can pinch. It is the deep abdominal fat that surrounds your organs. Its accumulation is a direct consequence of estrogen deficiency and a primary driver of metabolic problems.

- Insulin Resistance ∞ A state where your cells become less responsive to the hormone insulin. This leads to higher blood sugar and insulin levels, straining the pancreas and affecting energy regulation.

- Atherogenic Dyslipidemia ∞ An unhealthy pattern of blood fats characterized by high triglycerides, high levels of small, dense LDL particles, and low levels of protective HDL cholesterol. This profile is a significant marker for future cardiovascular risk.

Intermediate

To truly grasp how early menopause alters metabolic health, we must move beyond the “what” and into the “how.” The metabolic changes are not random; they are the direct, physiological consequences of withdrawing a key signaling molecule, estradiol, from a system that evolved to depend on it.

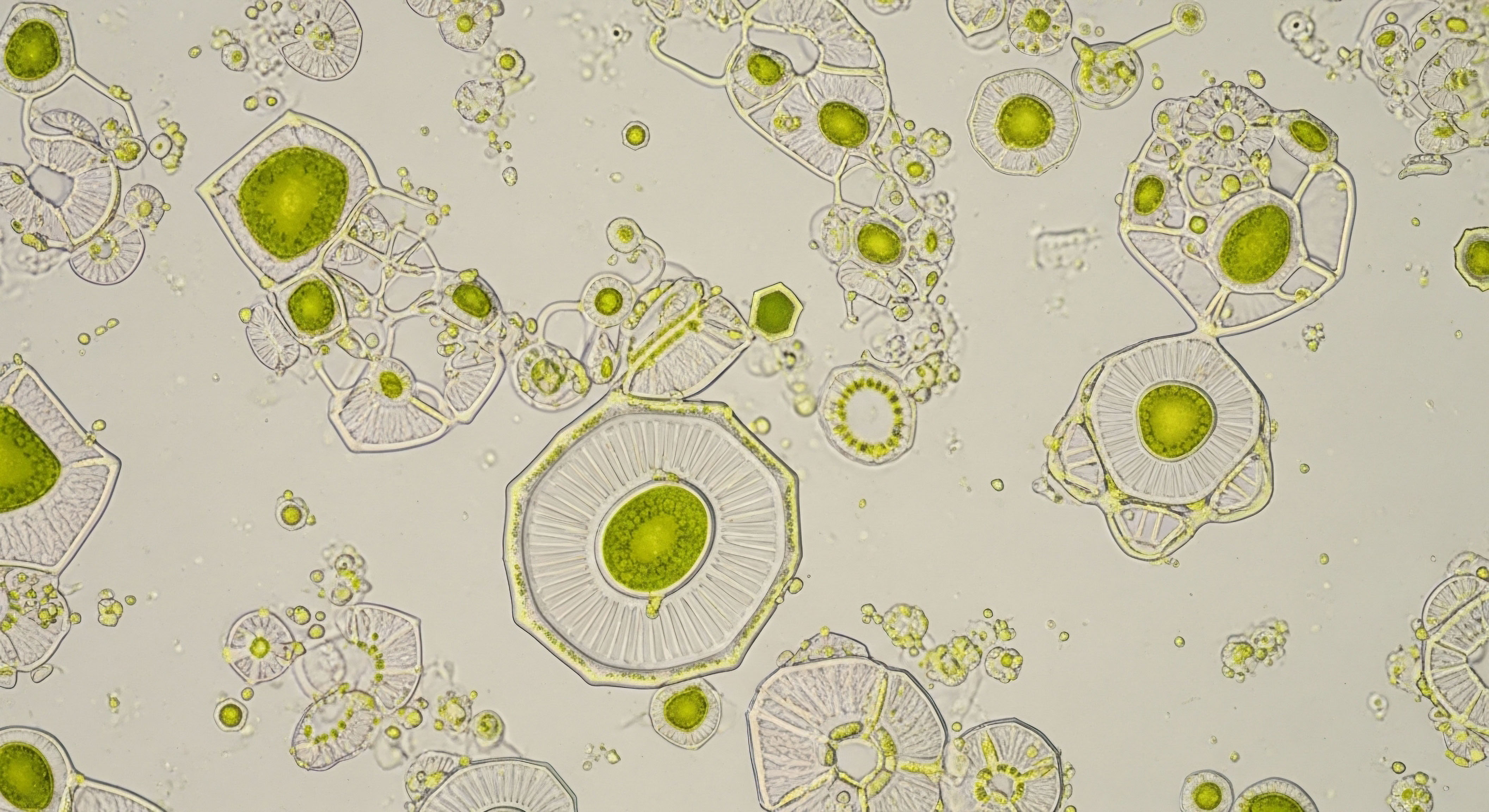

The conversation happens at the cellular level, through specific docking stations known as receptors. Understanding the function of these receptors, particularly Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ERα), is the key to deciphering the metabolic code of menopause.

Think of estradiol as a key and ERα as a specific lock found on cells throughout your body ∞ in your muscles, your liver, your fat tissue, and the lining of your blood vessels. When the key (estradiol) fits into the lock (ERα), it triggers a cascade of downstream events that promote metabolic health.

When the key is no longer available, these protective signals cease, and the system defaults to a less optimal state. Early menopause removes the master key from circulation, leaving these critical locks empty.

The Cellular Mechanisms of Metabolic Disruption

The metabolic consequences of early menopause can be traced back to the loss of ERα activation in key tissues. Each tissue responds to this loss in a unique way, but the cumulative effect is a systemic shift away from metabolic efficiency and resilience.

Muscle and Liver the Engines of Glucose Control

Your skeletal muscle is the primary site for glucose disposal after a meal. Healthy muscle tissue is highly sensitive to insulin and readily absorbs glucose from the blood. Estradiol, acting through ERα, directly enhances this process. It amplifies the insulin signal within the muscle cell, ensuring that glucose is efficiently taken up and used for energy or stored as glycogen for later use.

When estradiol is absent, this amplification is lost. The muscle becomes less responsive to insulin, leaving more glucose circulating in the blood.

Simultaneously, the liver, which stores and produces glucose, also falls under the influence of estradiol. Estrogen signaling helps to suppress hepatic glucose production, preventing the liver from releasing too much sugar into the bloodstream, especially during fasting states. The decline in estrogen during early menopause removes this suppressive signal, contributing further to elevated blood glucose and insulin levels.

Adipose Tissue the Fat Depots

The role of ERα in fat cells is twofold. First, it dictates fat distribution, promoting storage in the metabolically benign subcutaneous depots and preventing accumulation in the visceral cavity. Second, it helps maintain the health of the fat cells themselves, promoting efficient fat storage and release. Without estradiol, this regulation is lost.

The body begins to preferentially store fat viscerally, and these visceral fat cells become larger and dysfunctional. They begin to leak free fatty acids into the bloodstream and release a host of inflammatory signals called cytokines, which directly worsen insulin resistance in other tissues like the muscle and liver, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of metabolic decline.

What Are the Strategies for Metabolic Restoration?

Understanding these mechanisms allows for a targeted, logical approach to intervention. The goal is to restore the signals that the body is missing, thereby mitigating the downstream metabolic consequences. This is achieved through precise hormonal optimization protocols and supported by therapies that target metabolic pathways directly.

Hormonal Optimization a Foundational Approach

For women experiencing premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) or early menopause, hormonal optimization is a cornerstone of care. This involves replacing the hormones the ovaries no longer produce to restore physiological levels and protective signaling.

The protocols are designed to mimic the body’s natural state as closely as possible:

- Estradiol ∞ This is the primary hormone being replaced. It is most often administered transdermally (via a patch or gel). This route is preferred because it allows estradiol to be absorbed directly into the bloodstream, bypassing the liver. This avoidance of the “first-pass metabolism” in the liver leads to a more favorable impact on clotting factors and lipids compared to oral forms.

- Progesterone ∞ For women who have a uterus, progesterone is prescribed alongside estrogen to protect the uterine lining. Micronized progesterone is often used as it is structurally identical to the hormone the body produces and is associated with a neutral or beneficial metabolic profile.

- Testosterone ∞ While often considered a male hormone, testosterone is also crucial for female health, contributing to libido, energy, mood, and lean muscle mass. In early menopause, testosterone levels also decline. Low-dose Testosterone Cypionate, administered via weekly subcutaneous injection, can be a vital component of a comprehensive protocol, helping to preserve the muscle mass that is so critical for maintaining insulin sensitivity and metabolic rate.

| Delivery Method | Metabolic Implications | Common Application |

|---|---|---|

| Transdermal Estradiol (Patch/Gel) | Considered the most metabolically favorable route. Bypasses the liver, avoiding negative impacts on clotting factors and inflammatory markers. | Standard of care for estrogen replacement in POI. |

| Oral Estradiol | Processed by the liver first, which can increase certain clotting factors and inflammatory proteins. May have a less favorable impact on triglycerides. | A viable option, but transdermal is often preferred for metabolic reasons. |

| Subcutaneous Testosterone | Provides stable levels of testosterone, supporting lean muscle mass, which is crucial for insulin sensitivity and overall metabolic rate. | Used in low doses for women to address symptoms of androgen insufficiency. |

| Oral Micronized Progesterone | Metabolically neutral. Does not counteract the positive cardiovascular effects of estradiol. | Used cyclically or continuously to protect the endometrium. |

Peptide Therapy a Supportive Intervention

Beyond direct hormonal replacement, peptide therapies can offer powerful, targeted support for metabolic health. Peptides are short chains of amino acids that act as precise signaling molecules. Growth hormone-releasing peptides, in particular, can help counteract some of the metabolic shifts seen in early menopause.

Peptide therapies work by stimulating the body’s own production of growth hormone, a key regulator of metabolism that also declines with age and hormonal changes.

Protocols often involve peptides like Ipamorelin and CJC-1295. These are administered via subcutaneous injection and work together to stimulate a natural, rhythmic release of growth hormone from the pituitary gland. The benefits are directly relevant to the metabolic challenges of early menopause:

- Reduced Visceral Fat ∞ Growth hormone is a powerful lipolytic agent, meaning it helps break down fat, particularly the visceral fat that accumulates after menopause.

- Increased Lean Body Mass ∞ By promoting the growth and repair of muscle tissue, these peptides help preserve the body’s metabolic engine.

- Improved Insulin Sensitivity ∞ By improving the body’s ratio of lean mass to fat mass, these therapies can have a positive secondary effect on overall insulin sensitivity.

These protocols work in concert. Hormonal optimization restores the body’s foundational signaling architecture, while peptide therapies provide targeted support to enhance fat metabolism and preserve the lean tissue that is essential for long-term metabolic vitality.

Academic

An academic exploration of early menopause and its metabolic sequelae requires a systems-biology perspective. The abrupt cessation of ovarian estradiol production is an endocrine event of the first order, initiating a complex and interconnected cascade of pathophysiological changes.

This process extends far beyond simple hormonal absence; it represents a fundamental dysregulation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis that reverberates through the body’s metabolic, inflammatory, and vascular networks. The resulting phenotype is one of accelerated metabolic aging, characterized by central adiposity, insulin resistance, atherogenic dyslipidemia, and endothelial dysfunction.

The Central Role of Estrogen Receptor Alpha Signaling

At the molecular level, the metabolic integrity of numerous tissues is predicated on intact signaling through Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ERα), a ligand-activated transcription factor encoded by the ESR1 gene. The loss of its ligand, 17β-estradiol, precipitates a coordinated failure of protective cellular mechanisms. Research using ERα knockout (ERαKO) mouse models has been instrumental in elucidating these pathways, demonstrating that the absence of ERα signaling recapitulates many of the metabolic derangements seen in postmenopausal women.

In skeletal muscle, ERα activation is integral to the non-genomic potentiation of the insulin signaling cascade. Estradiol binding to ERα enhances insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of Insulin Receptor Substrate-1 (IRS-1) and the subsequent activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway.

This pathway is the final common road for stimulating the translocation of the GLUT4 glucose transporter to the cell membrane, the rate-limiting step for muscle glucose uptake. The loss of this estrogen-mediated enhancement uncouples insulin binding from its full downstream effect, manifesting as clinical insulin resistance.

How Does Visceral Adiposity Drive Systemic Inflammation?

The redistribution of adipose tissue from subcutaneous to visceral depots is a hallmark of the hypoestrogenic state. Visceral adipose tissue (VAT) is not a passive storage site; it is an endocrine organ that, in a state of excess, becomes highly pro-inflammatory.

Hypertrophic visceral adipocytes are infiltrated by macrophages, creating a microenvironment rich in inflammatory cytokines such as Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) and Interleukin-6 (IL-6). These cytokines act both locally and systemically to exacerbate insulin resistance. TNF-α, for example, can directly interfere with the insulin receptor’s tyrosine kinase activity, further impairing insulin signaling in muscle and liver tissue.

This state of chronic, low-grade inflammation, originating in VAT, is a key mechanistic link between the hormonal changes of early menopause and the development of metabolic syndrome.

Cardiovascular Pathophysiology Endothelial Dysfunction and Dyslipidemia

The vascular endothelium, the single-cell layer lining all blood vessels, is a critical regulator of vascular tone and health. It is highly responsive to estradiol. Estrogen, via ERα, stimulates the endothelial production of nitric oxide (NO), a potent vasodilator and anti-inflammatory molecule.

NO is essential for maintaining vascular compliance and preventing the adhesion of platelets and leukocytes to the vessel wall, which are initiating steps in atherosclerosis. The premature loss of estradiol leads directly to endothelial dysfunction, characterized by reduced NO bioavailability. This is one of the earliest events in the development of cardiovascular disease and is demonstrably improved with the initiation of transdermal hormone therapy in women with premature ovarian insufficiency.

This vascular insult is compounded by the development of atherogenic dyslipidemia. The hypoestrogenic state promotes increased hepatic production of very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) and a reduction in the activity of lipoprotein lipase, the enzyme that clears triglycerides from the blood. This results in hypertriglyceridemia and an increase in the number of small, dense LDL (sdLDL) particles.

These sdLDL particles are particularly dangerous because they are more easily oxidized and can more readily penetrate the arterial intima, contributing directly to the formation of atherosclerotic plaques.

The premature withdrawal of estradiol initiates a dual assault on the cardiovascular system by impairing endothelial function and promoting a highly pro-atherogenic lipid profile.

Advanced Therapeutic Protocols a Systems-Based Intervention

A sophisticated clinical approach seeks to address these interconnected pathologies. While foundational HRT restores systemic estradiol and progesterone, advanced protocols may incorporate other agents to target specific downstream consequences, such as the accumulation of visceral fat or the decline in anabolic signaling.

Targeting the GH/IGF-1 Axis with Peptide Therapy

The somatotropic axis (GH/IGF-1) also declines with age, a process that is accelerated by the menopausal transition. Growth hormone is a primary regulator of body composition. Peptide therapies that stimulate endogenous GH secretion, such as Tesamorelin, offer a targeted strategy to counteract the adverse body composition changes of early menopause.

Tesamorelin is a synthetic analogue of growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) that has been shown in clinical trials to significantly reduce visceral adipose tissue. Its mechanism is precise ∞ it stimulates the pituitary to release GH, which in turn promotes lipolysis in VAT and increases lean body mass. This intervention directly targets a central driver of the metabolic syndrome.

| Peptide | Mechanism of Action | Relevance to Early Menopause |

|---|---|---|

| Tesamorelin | GHRH analogue; stimulates endogenous growth hormone release from the pituitary gland. | Directly targets and reduces visceral adipose tissue, a key driver of insulin resistance and inflammation. |

| CJC-1295 / Ipamorelin | A GHRH analogue (CJC-1295) combined with a Ghrelin mimetic (Ipamorelin) to create a potent, synergistic GH release. | Promotes lipolysis, increases lean muscle mass, and can improve sleep quality, which has secondary metabolic benefits. |

| PT-141 (Bremelanotide) | Melanocortin receptor agonist; primarily acts in the central nervous system to influence sexual arousal. | Addresses the common symptom of diminished libido, linking metabolic restoration with quality of life and sexual health. |

| MK-677 (Ibutamoren) | Oral ghrelin mimetic and growth hormone secretagogue. | Increases GH and IGF-1 levels, supporting lean mass and bone density, though it can also increase appetite and insulin resistance in some individuals. |

Why Is Restoring Systemic Balance the Ultimate Goal?

The ultimate therapeutic objective is to move beyond single-symptom management and toward a restoration of systemic physiological balance. The protocols described, from foundational hormonal optimization with bioidentical estradiol and progesterone to the adjunctive use of low-dose testosterone and targeted peptide therapies, represent a multi-pronged strategy.

This approach recognizes that the metabolic consequences of early menopause are interconnected. By restoring key hormonal signals and supporting anabolic pathways, it is possible to mitigate the shift towards visceral adiposity, improve insulin sensitivity, correct dyslipidemia, and preserve the endothelial function that is so vital for long-term cardiovascular health. This integrated, evidence-based model provides a comprehensive framework for managing the profound metabolic challenges posed by premature estrogen deficiency.

References

- Ribas, V. et al. “Loss of Estrogen Receptor α Signaling Leads to Insulin Resistance and Obesity in Young and Adult Female Mice.” Cell Reports, vol. 1, no. 8, 2016, pp. 645-657.

- Podfigurna-Stopa, A. et al. “Premature ovarian insufficiency ∞ hormone replacement therapy and management of long-term consequences.” Endokrynologia Polska, vol. 69, no. 5, 2018, pp. 594-603.

- Carr, M. C. “The Emergence of the Metabolic Syndrome with Menopause.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 88, no. 6, 2003, pp. 2404-2411.

- El-Khoudary, S. R. et al. “Menopause Transition and Cardiovascular Disease Risk ∞ Implications for Timing of Early Prevention ∞ A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association.” Circulation, vol. 142, no. 25, 2020, e506-e543.

- Bikman, Ben. “The Metabolic Classroom ∞ The Impact of Estrogens on Glucose Metabolism and Insulin Resistance.” YouTube, 16 Aug. 2024.

- Muka, T. et al. “Association of Age at Onset of Menopause and Time Since Onset of Menopause With Cardiovascular Outcomes, Intermediate Vascular Traits, and All-Cause Mortality ∞ A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” JAMA Cardiology, vol. 1, no. 7, 2016, pp. 767-776.

- He, Ling, et al. “Novel Peptide Therapy Shows Promise for Treating Obesity, Diabetes and Aging.” Cell Chemical Biology, vol. 30, no. 10, 2023.

- Rosano, G. M. C. et al. “Menopause and cardiovascular disease ∞ the evidence.” Climacteric, vol. 20, no. 2, 2017, pp. 1-7.

- Faubion, S. S. et al. “Hormone therapy for postmenopausal women.” The Lancet, vol. 394, no. 10205, 2019, pp. 1260-1271.

- “Peptides for Weight Loss ∞ A Functional Medicine Guide.” CentreSpring MD, 2024.

Reflection

The information presented here offers a map, a detailed guide to the biological territory you find yourself in. It translates the abstract language of endocrinology and metabolic science into a tangible understanding of your own body’s experience. This knowledge is a powerful tool. It transforms confusion into clarity and a sense of victimhood into one of agency. The journey through early menopause is a deeply personal one, and this map is designed to help you navigate it with confidence.

Your unique physiology, history, and goals will determine your specific path forward. The purpose of this deep exploration is to equip you for a meaningful conversation with a clinical guide who can help you interpret your own metabolic story. The path to reclaiming your vitality begins not with a single answer, but with the right questions.

You now possess a framework for asking them. The potential to restore your body’s intended function and to build a future of resilient health is within your reach.

Glossary

metabolic health

early menopause

visceral adipose tissue

insulin resistance

atherogenic dyslipidemia

adipose tissue

estrogen receptor alpha

visceral fat

hormonal optimization

premature ovarian insufficiency

insulin sensitivity

lean muscle mass

peptide therapies

growth hormone

ipamorelin

cjc-1295

endothelial dysfunction

estrogen receptor

metabolic syndrome

tesamorelin