Fundamentals

When you begin to consider testosterone therapy, the immediate focus is often on alleviating symptoms like fatigue, low libido, or mental fog. The conversation centers on restoring vitality. A deeper, equally important question emerges when considering the therapy’s endpoint ∞ what happens when you stop?

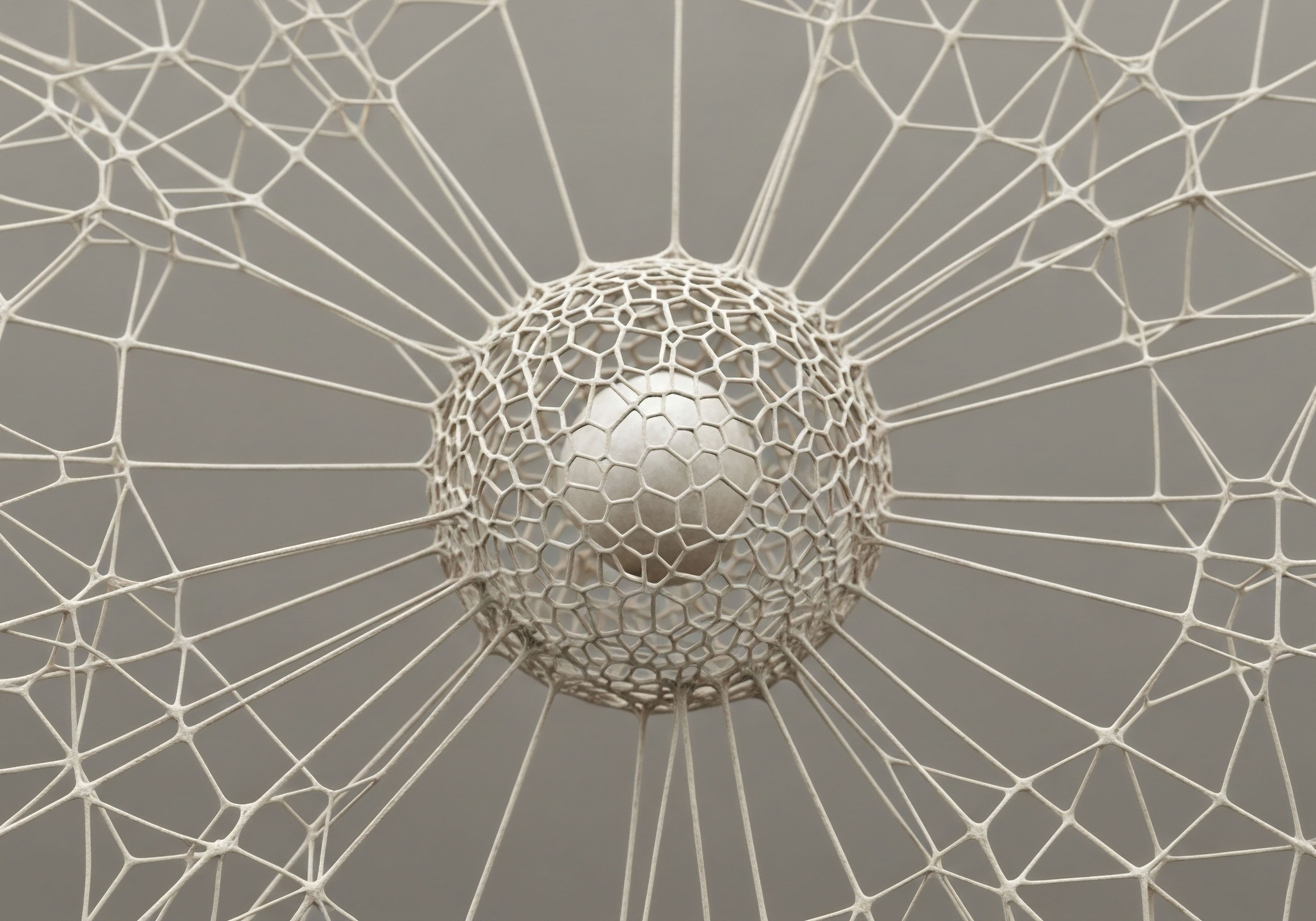

The answer lies within a sophisticated biological communication network known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. This system is the body’s internal command center for reproductive health and hormonal balance, a finely tuned orchestra where the brain and testes engage in constant dialogue.

Introducing external testosterone, as in Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT), is akin to bringing in a powerful lead instrument that temporarily quiets the conductor. The hypothalamus, located in the brain, senses the abundance of testosterone and reduces its signaling molecule, Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH).

This, in turn, instructs the pituitary gland, another key brain structure, to decrease its output of Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). These are the very signals that tell the testes to produce their own testosterone and to support sperm maturation.

The longer this external “instrument” plays, the more accustomed the internal “orchestra” becomes to its silence. Recovery, therefore, is the process of encouraging your body’s natural conductor to pick up the baton once more and restart its own symphony.

The duration of testosterone therapy directly influences the time it takes for the body’s natural hormonal signaling to resume.

The timeline for this recalibration is intensely personal. It is governed by the length of time you were on therapy, your dosage, the specific type of testosterone used, and your own unique physiological landscape before treatment began. For some, the return to baseline function can occur over a matter of months.

For others, particularly after years of therapy, the process can be more prolonged, sometimes taking a year or more. This variability underscores a central principle of endocrinology ∞ biological systems possess a memory. The longer the HPG axis is suppressed, the deeper its slumber, and the more time it requires to fully reawaken.

Understanding this process is about recognizing the body’s remarkable capacity for self-regulation. The cessation of therapy is not a simple switch being flipped. It is a gradual, biological handover of responsibility from an external source back to your own internal production system. This period of readjustment is a testament to the intricate feedback loops that govern our physiology, a journey back to self-sufficiency that requires patience and informed clinical guidance.

Intermediate

The recovery of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis following the discontinuation of testosterone therapy is a complex physiological process governed by the principle of negative feedback. When exogenous testosterone is administered, the hypothalamus and pituitary gland perceive high androgen levels, leading to a down-regulation of GnRH, LH, and FSH production.

This state, known as exogenous-androgen-induced hypogonadism, is the intended consequence of the therapy’s mechanism. The duration of this suppression is a primary determinant of the recovery trajectory. Short-term use may result in a relatively swift rebound, while long-term administration creates a more profound and lasting suppression that requires a more structured and patient approach to reversal.

Factors Influencing the Recovery Timeline

The time required for the HPG axis to regain its autonomous function is not uniform. Several key variables interact to determine the specific timeline for an individual. Acknowledging these factors is essential for setting realistic expectations and designing an effective post-therapy strategy.

- Duration of Therapy ∞ This is arguably the most significant factor. Clinical evidence suggests a direct correlation between the length of testosterone administration and the time to HPG axis recovery. Periods of use extending beyond one year often necessitate a longer recovery phase compared to shorter cycles.

- Dosage and Formulation ∞ Higher doses of testosterone can induce a more profound suppression of gonadotropins. The formulation also plays a role; long-acting injectable esters like testosterone undecanoate may require a more extended washout period than shorter-acting topical gels or creams.

- Pre-Therapy Baseline Function ∞ An individual’s testicular function and HPG axis integrity before initiating therapy are strong predictors of recovery potential. Men with primary hypogonadism (testicular failure) may not recover full function, whereas those with secondary hypogonadism (pituitary or hypothalamic issues) may have a different recovery pattern.

- Age ∞ Older individuals may experience a slower or less complete recovery of the HPG axis and spermatogenesis compared to younger men.

What Does the Clinical Data Suggest for Recovery Timelines?

Clinical studies provide a framework for understanding typical recovery timelines, though individual results can vary. Research indicates that for many men, spontaneous recovery of spermatogenesis and endogenous testosterone production is achievable, but patience is paramount. A significant portion of men may see sperm return to the ejaculate within 6 to 12 months after stopping therapy.

However, a full return to pre-treatment baseline levels for hormones like LH and FSH can take approximately 12 months or longer in some cases. Some studies report that recovery could extend up to 24 months, particularly after prolonged use of anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS), which are related compounds.

Recovery of the HPG axis is a gradual process, with hormonal markers like LH and FSH often taking up to a year to normalize after long-term therapy.

The table below outlines a generalized, phased expectation for HPG axis recovery after discontinuing long-term TRT, based on available clinical data. This is an illustrative model, and individual experiences will differ.

| Recovery Phase | Typical Timeframe | Key Biological Events |

|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 ∞ Washout & Initial Rebound | 0-3 Months Post-Cessation |

Exogenous testosterone clears from the system. The hypothalamus begins to sense low androgen levels and slowly resumes GnRH pulses. Pituitary sensitivity to GnRH starts to return. |

| Phase 2 ∞ Gonadotropin Rise | 3-9 Months Post-Cessation |

LH and FSH levels begin to rise more consistently, stimulating the Leydig and Sertoli cells in the testes. Endogenous testosterone production and spermatogenesis slowly restart. |

| Phase 3 ∞ Hormonal Stabilization | 9-18+ Months Post-Cessation |

HPG axis feedback loops begin to stabilize. Endogenous testosterone levels approach the individual’s baseline. Spermatogenesis continues to improve, though full recovery can take longer. |

Post-TRT Recovery Protocols

For individuals seeking to expedite recovery, particularly for fertility purposes or to mitigate symptoms of temporary hypogonadism, specific clinical protocols may be employed. These are designed to actively stimulate the HPG axis.

A common approach involves using agents like Gonadorelin, a GnRH analogue, to directly stimulate the pituitary gland. Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) such as Clomiphene (Clomid) or Tamoxifen are also frequently used. These medications block estrogen’s negative feedback at the hypothalamus and pituitary, effectively tricking the brain into increasing LH and FSH output.

This strategy provides a direct stimulus to the testes, encouraging them to resume their natural function more quickly than they might spontaneously. The use of Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG), which mimics LH, is another established method to directly stimulate the testes.

Academic

The recalibration of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis following cessation of exogenous testosterone administration is a nuanced process rooted in the neuroendocrine principles of feedback inhibition and neuronal plasticity. The duration of therapy is a critical variable that dictates the degree of functional suppression and, consequently, the architecture of the recovery period.

Prolonged exposure to supraphysiological or even physiological levels of exogenous androgens induces profound adaptive changes within the GnRH pulse generator in the hypothalamus and alters the sensitivity of gonadotroph cells in the anterior pituitary.

Neuroendocrine Mechanisms of HPG Axis Suppression

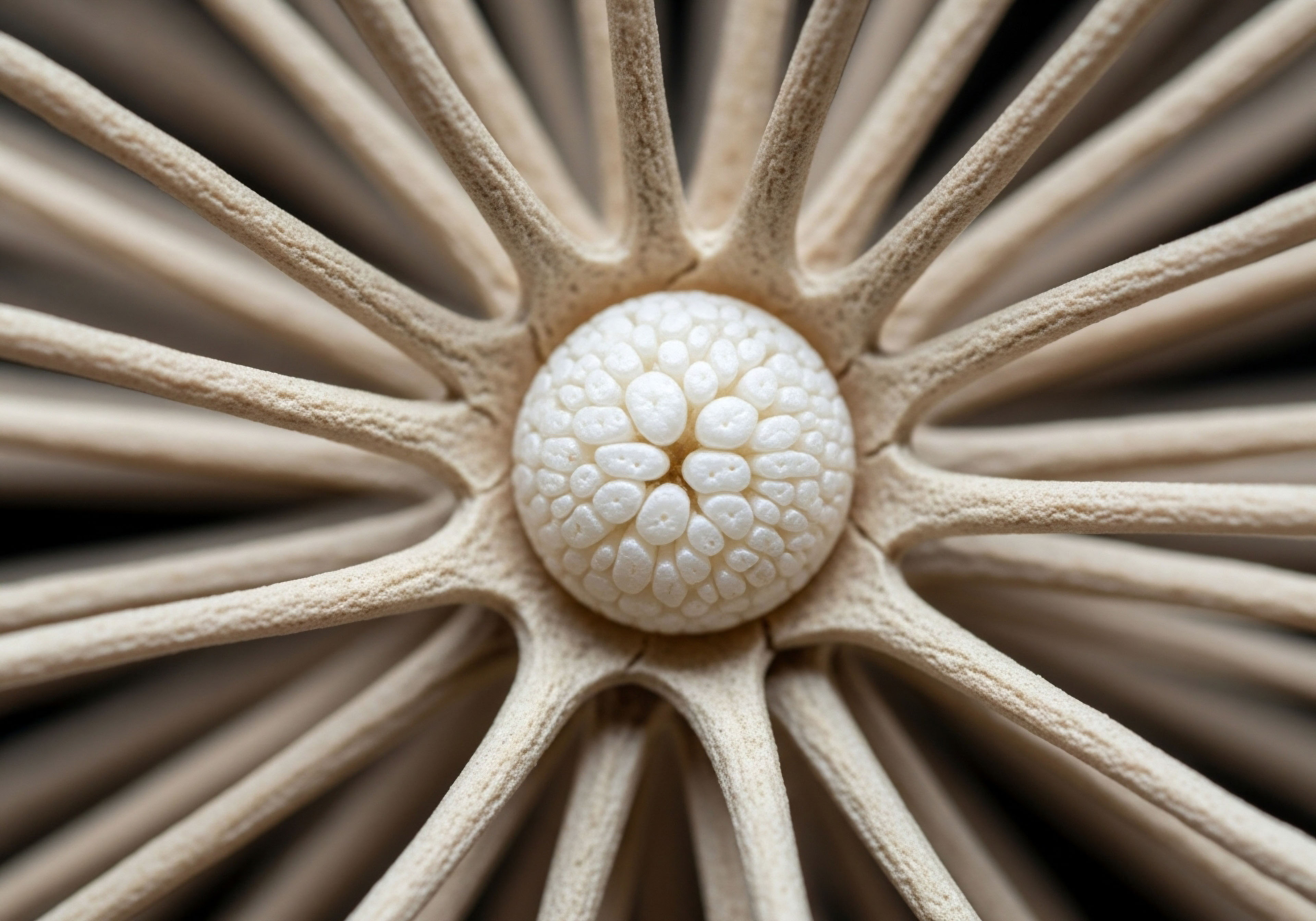

The primary mechanism of suppression involves the negative feedback exerted by testosterone and its metabolite, estradiol, on the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus Kiss1-expressing neurons (KNDy neurons). These neurons are the central regulators of the GnRH pulse generator. Chronic androgen exposure leads to a sustained inhibition of Kiss1 gene expression and a reduction in the frequency and amplitude of GnRH pulses.

This, in turn, results in diminished synthesis and secretion of the gonadotropins, LH and FSH, from the pituitary gland. The Leydig cells of the testes, deprived of their trophic LH signal, cease endogenous testosterone production, while the Sertoli cells, lacking FSH stimulation, down-regulate their supportive role in spermatogenesis.

The duration of this induced state of central hypogonadism directly impacts the recovery potential. Long-term suppression may lead to changes beyond simple feedback inhibition, potentially involving alterations in receptor density, downstream signaling pathways, and even epigenetic modifications within the hypothalamic and pituitary cells. The recovery process, therefore, is not merely the removal of an inhibitory signal but an active process of cellular and systemic recalibration.

How Does Duration Quantitatively Impact Recovery Metrics?

Quantitative analysis from clinical trials provides insight into the temporal dynamics of recovery. One study investigating recovery after two years of injectable testosterone undecanoate treatment found that the median time for serum LH to return to its pre-treatment baseline was 51.1 weeks. The time for FSH to recover was slightly longer, at a median of 52.7 weeks.

This highlights that a return to baseline gonadotropin levels after extended therapy is a year-long process for the average individual in the study cohort.

Further research has sought to create predictive models for recovery. Probability estimates suggest that after discontinuing testosterone, spermatogenesis (defined as reaching a concentration of 20 million sperm/mL) is achieved by 67% of men at 6 months, 90% at 12 months, and nearly 100% by 24 months. These data also identify longer duration of use and older age as factors that significantly prolong this recovery timeline.

A study on former anabolic steroid users found a strong negative correlation between the duration of use and the likelihood of successful HPG axis restoration after a three-month cessation period.

The protracted recovery timeline after long-term TRT reflects a deep-seated adaptation of the GnRH pulse generator, requiring substantial time to restore its intrinsic rhythm.

The following table details specific hormonal and cellular events during the recovery phase, emphasizing the impact of long-duration therapy.

| Parameter | Mechanism of Suppression | Recovery Pathway and Timeline |

|---|---|---|

| GnRH Pulse Generator |

Sustained negative feedback from androgens/estrogens on KNDy neurons in the hypothalamus, reducing GnRH pulse frequency and amplitude. |

Gradual restoration of KNDy neuron activity as androgen levels fall. May involve neuronal plasticity and receptor re-sensitization. Can take 6-12 months to fully re-establish a normal pulsatile pattern. |

| Pituitary Gonadotropes |

Down-regulation of GnRH receptors and direct inhibition of LH/FSH synthesis and secretion. |

Requires restored GnRH stimulation to up-regulate receptor expression and resume gonadotropin synthesis. LH recovery often precedes FSH recovery. Typically requires 9-12 months to reach baseline. |

| Leydig Cell Function |

Atrophy and functional quiescence due to chronic lack of LH stimulation. |

Re-stimulation by rising endogenous LH initiates steroidogenesis. Full recovery of steroidogenic capacity is dependent on the duration of dormancy. |

| Spermatogenesis |

Arrest of germ cell development due to suppression of both intratesticular testosterone and FSH signaling to Sertoli cells. |

A full cycle of spermatogenesis takes ~74 days, but restoring the necessary hormonal milieu (high ITT and FSH) can take many months. Recovery to baseline sperm counts can take 12-24 months. |

The Role of Post-Cycle Therapy in Modulating Recovery

From a pharmacological standpoint, Post-Cycle Therapy (PCT) protocols are designed to intervene at specific points in this suppressed axis. SERMs, like clomiphene citrate, function as estrogen receptor antagonists at the level of the hypothalamus and pituitary.

By blocking the inhibitory feedback of estradiol, they effectively increase the perceived estrogen deficit, which stimulates a robust increase in GnRH release and subsequent LH/FSH secretion. This provides a potent, albeit artificial, stimulus to the gonads.

Similarly, the use of hCG acts as an LH mimetic, directly stimulating the Leydig cells to produce testosterone, which can help maintain testicular volume and steroidogenic capacity during the recovery period. The strategic use of these agents can shorten the symptomatic phase of hypogonadism post-cessation, although the ultimate goal remains the restoration of the patient’s own endogenous, stable HPG axis rhythm.

References

- Ramasamy, R. et al. “Recovery of spermatogenesis following testosterone replacement therapy or anabolic-androgenic steroid use.” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 105, no. 3, 2016, pp. 583-8.

- Yeap, B. B. et al. “Recovery of Male Reproductive Endocrine Function Following Prolonged Injectable Testosterone Undecanoate Treatment.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 106, no. 7, 2021, pp. e2624-e2635.

- Liu, P. Y. et al. “The rate, extent, and modifiers of spermatogenic recovery after hormonal contraception in men.” The Lancet, vol. 363, no. 9416, 2004, pp. 1179-86.

- Lykhonosov, M. P. et al. “.” Problemy Endokrinologii, vol. 66, no. 4, 2020, pp. 43-51.

- Wheeler, K. M. et al. “A review of the role of testosterone in stimulating and suppressing spermatogenesis.” Journal of Andrology, vol. 17, no. 5, 1996, pp. 523-34.

Reflection

Charting Your Personal Path to Hormonal Autonomy

The clinical data and biological mechanisms provide a map, but you are the cartographer of your own health journey. Understanding how the duration of therapy impacts your internal hormonal landscape is the first step. This knowledge transforms you from a passive recipient of care into an active participant in your own wellness.

It shifts the focus from a simple question of “when will I recover?” to a more empowering inquiry ∞ “what does my body need to restore its own inherent balance?”

This journey of recalibration is a profound dialogue with your own physiology. Each blood test, each subtle return of your body’s natural rhythm, is a piece of information. The path forward is one of observation, patience, and partnership with a clinical team that understands the intricate science and respects your individual experience. The ultimate goal is to reclaim a state of vitality that is generated from within, a testament to your body’s remarkable capacity for self-regulation and resilience.

Glossary

testosterone therapy

testosterone replacement therapy

gonadotropin-releasing hormone

follicle-stimulating hormone

luteinizing hormone

hpg axis

negative feedback

pituitary gland

hpg axis recovery

secondary hypogonadism

spermatogenesis

endogenous testosterone production

endogenous testosterone

sertoli cells

gnrh pulse generator

gnrh pulse

injectable testosterone undecanoate treatment

clomiphene citrate