Fundamentals

You may have noticed a persistent fatigue, a sense that your body is running on empty. This feeling is a valid and important signal. It is your body communicating a state of profound and prolonged demand. We can begin to understand this experience by examining the intricate relationship between chronic stress and the body’s systems of repair and rejuvenation, governed in large part by Growth Hormone (GH).

Your body possesses a sophisticated system for managing threats, known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. Think of it as an internal emergency response team. When faced with a stressor ∞ be it a demanding job, emotional turmoil, or lack of sleep ∞ the HPA axis is activated. This activation culminates in the release of cortisol, a primary stress hormone. In short bursts, cortisol is incredibly useful, preparing the body for immediate action.

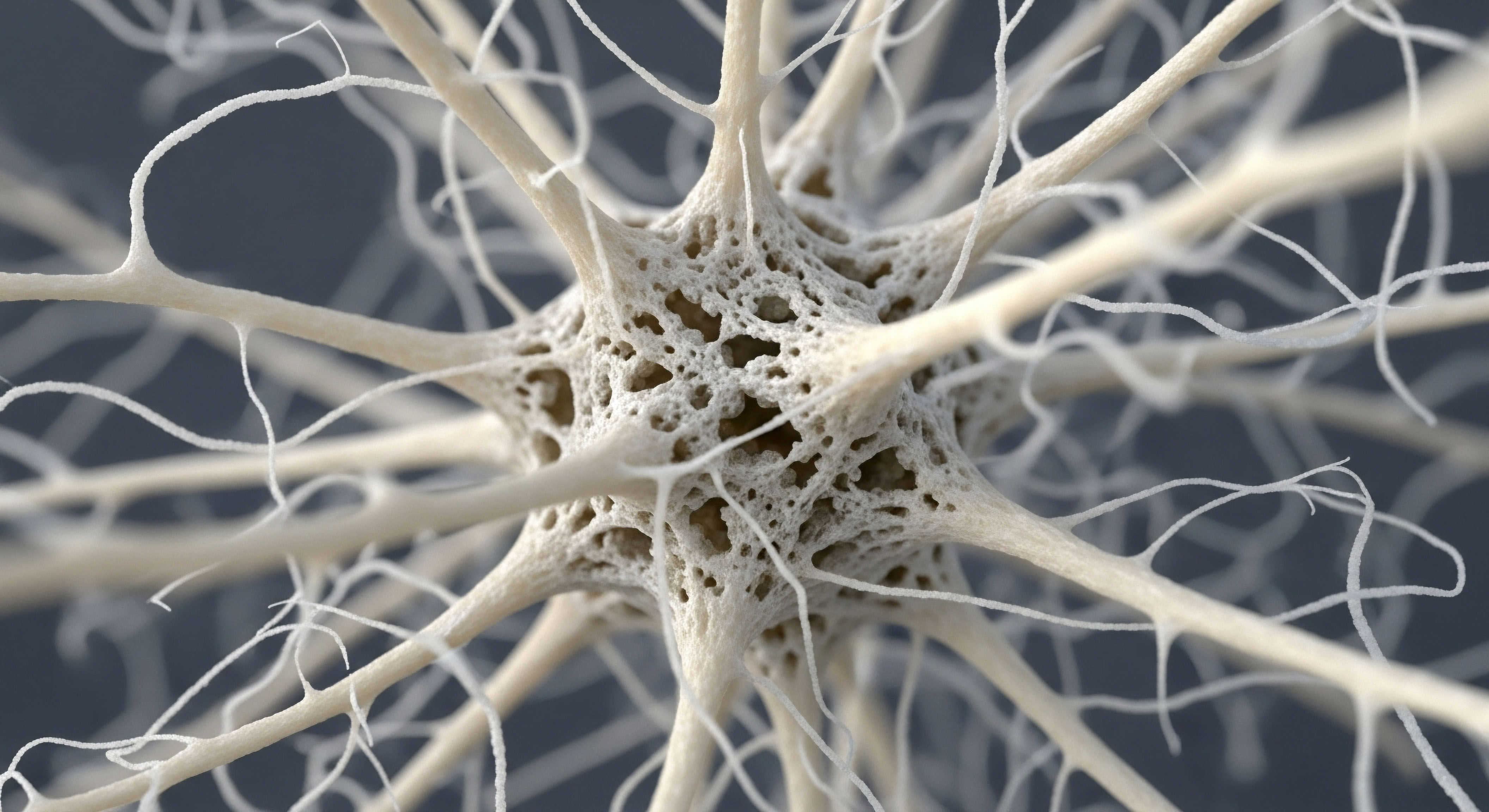

The system that regulates GH, however, operates with a different objective. The Growth Hormone axis is geared toward long-term projects of growth, repair, and metabolic maintenance. It is responsible for tissue regeneration, maintaining lean body mass, and optimizing energy use. These two systems, the emergency response and the long-term maintenance crew, are in constant communication.

When the emergency system is perpetually active, it tells the maintenance crew to stand down. Resources must be conserved for the ongoing crisis, and long-term projects are put on hold.

Chronic activation of the body’s stress system directly leads to the suppression of the Growth Hormone axis, prioritizing immediate survival over long-term repair and growth.

The Hormonal Conversation

This communication occurs through a sophisticated chemical language. The hypothalamus, a control center in the brain, releases two key hormones that govern GH secretion from the pituitary gland:

- Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone (GHRH) acts as the accelerator, signaling the pituitary to release GH.

- Somatostatin functions as the brake, telling the pituitary to halt GH release.

Under conditions of chronic stress, the balance of this conversation shifts dramatically. The sustained production of cortisol and other stress-related signals amplifies the “brake” signal of somatostatin. At the same time, it quiets the “accelerator” signal of GHRH. The pituitary gland receives a clear, consistent message ∞ stop producing growth hormone.

This is a biological strategy to save energy. The body perceives the chronic stress as a threat so significant that it cannot afford the metabolic cost of building and repairing tissues. The consequence is a systemic slowdown in the very processes that contribute to vitality and resilience.

What Does Suppressed Growth Hormone Feel Like?

The clinical science directly connects to your lived experience. When GH levels are consistently suppressed, the body’s capacity for daily repair is diminished. This can manifest in several ways:

- A persistent feeling of fatigue that sleep does not seem to resolve.

- Difficulty recovering from physical activity or minor injuries.

- Changes in body composition, such as an increase in abdominal fat and a decrease in muscle tone.

- A general decline in physical and mental stamina.

These are not isolated symptoms. They are logical outcomes of a system that has been forced to prioritize short-term survival over long-term health. Understanding this biological context is the first step in addressing the root cause and recalibrating your internal systems.

Intermediate

To fully appreciate the impact of chronic stress on growth hormone, we must examine the specific biochemical pathways that connect the body’s stress and growth axes. The sustained elevation of glucocorticoids, particularly cortisol, initiates a cascade of inhibitory effects that systematically dismantle the machinery of GH secretion and action. This process is not a simple on/off switch; it is a multi-level suppression that affects the entire GH system from the brain to the peripheral tissues.

The Central Command Disruption

The primary disruption occurs within the hypothalamus. Chronic stress leads to a sustained increase in corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), the initial signal in the HPA axis cascade. This elevated CRH has a direct inhibitory effect on the production of Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone (GHRH). With less GHRH, the pituitary gland receives a weaker signal to produce GH. Simultaneously, CRH stimulates the release of somatostatin, the primary inhibitor of GH secretion. This creates a powerful dual-suppression mechanism at the source.

The table below illustrates the contrasting effects of acute versus chronic stress on the hormonal environment, highlighting the shift from a temporary, adaptive response to a prolonged, maladaptive state.

| Stressor Type | HPA Axis Response (Cortisol) | GHRH Secretion | Somatostatin Secretion | Net Effect on GH Secretion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Stress (e.g. intense exercise) | Transient Spike | Increased | Temporarily Decreased | Stimulated |

| Chronic Stress (e.g. prolonged emotional duress) | Sustained Elevation | Decreased | Increased | Inhibited |

How Does the Pituitary Gland Respond to Conflicting Signals?

The pituitary gland itself becomes less responsive to any available GHRH. Elevated cortisol levels are understood to reduce the sensitivity of the pituitary cells, known as somatotrophs, to GHRH stimulation. Even if some “go” signal gets through, the pituitary’s ability to execute the command is impaired.

This creates a state of functional resistance at the very site of GH production. The result is a significant reduction in both the frequency and amplitude of GH pulses, which are essential for its physiological effects.

Sustained high levels of cortisol create a state of pituitary resistance, weakening the gland’s ability to secrete growth hormone even when stimulated.

Peripheral Resistance the Final Blockade

The suppressive effects of chronic stress extend beyond the brain and pituitary. Growth hormone exerts many of its effects by stimulating the liver and other tissues to produce Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1). IGF-1 is a powerful anabolic hormone that mediates much of the cell growth, repair, and proliferation attributed to GH. Chronic stress interferes with this critical step in two ways:

- Hepatic Resistance ∞ Elevated cortisol levels can make the liver less responsive to GH, leading to reduced IGF-1 production. Therefore, even the diminished amount of GH circulating in the body is less effective at producing its key downstream mediator.

- Increased Binding Proteins ∞ Stress can alter the levels of IGF-binding proteins (IGFBPs), which regulate the bioavailability of IGF-1 in the bloodstream. Some of these proteins can sequester IGF-1, preventing it from reaching its target receptors in tissues like muscle and bone.

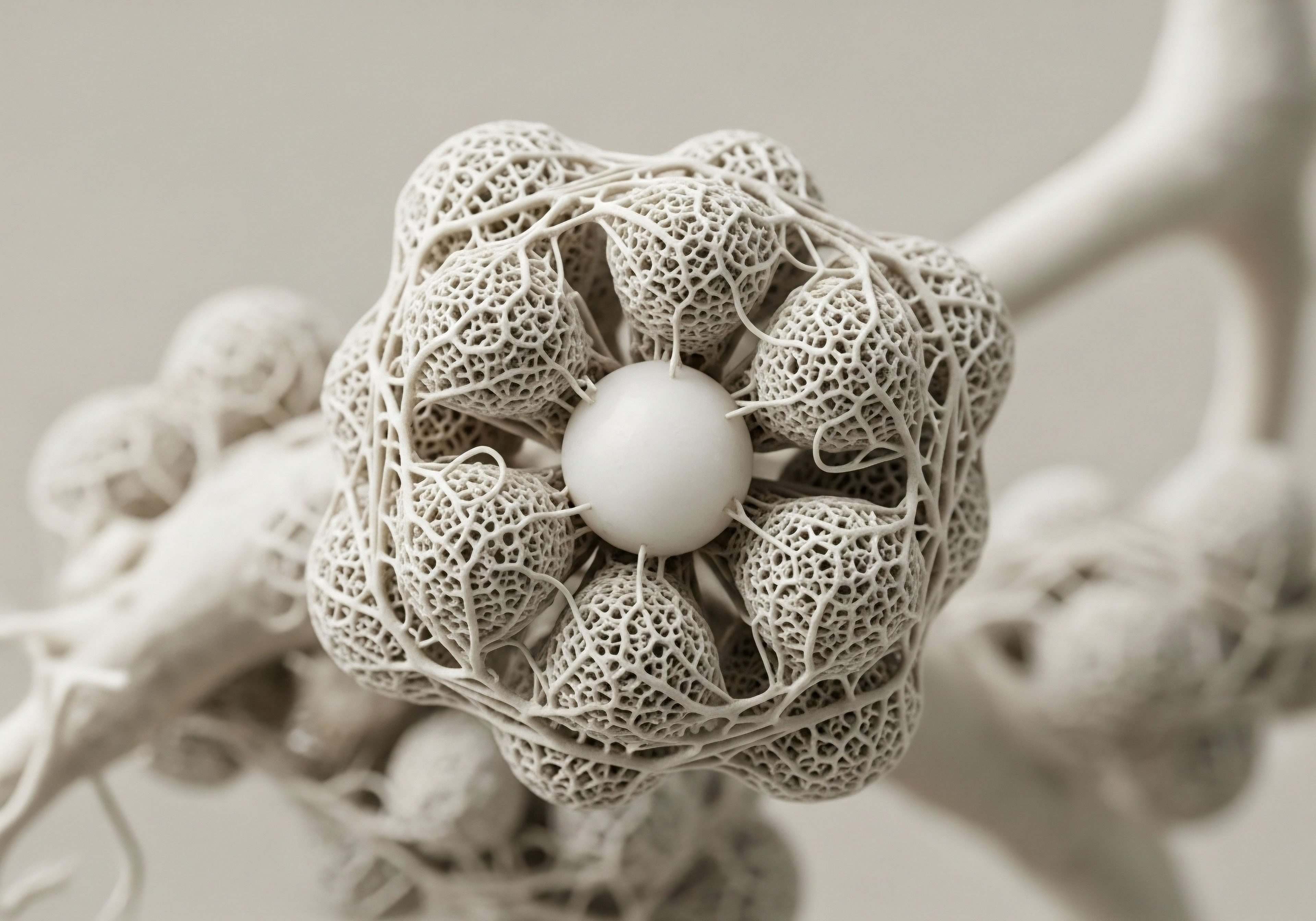

This multi-pronged assault ∞ reducing GHRH, increasing somatostatin, desensitizing the pituitary, and inducing peripheral resistance ∞ demonstrates how chronic stress systematically dismantles the growth hormone axis. The result is a state of GH insufficiency and resistance that has profound implications for metabolic health, body composition, and overall vitality. Understanding these mechanisms is foundational for developing targeted interventions, such as Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy, which can help restore the signaling balance within this intricate system.

Academic

The intricate interplay between the neuroendocrine stress response and the somatotropic (GH) axis represents a fundamental biological trade-off between immediate survival and long-term anabolic processes. A deep examination of this relationship reveals that chronic stress induces a state of functional growth hormone resistance, a phenomenon mediated by complex molecular and cellular adaptations.

This goes beyond simple suppression of GH secretion and involves downstream desensitization of target tissues, particularly through the modulation of the GH receptor (GHR) and its signaling pathways, as well as alterations in gene expression.

Molecular Mechanisms of GH Resistance in Chronic Stress

The cellular response to GH is initiated by its binding to the GHR, a transmembrane protein that activates the Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) signaling pathway. This phosphorylation cascade ultimately leads to the activation of the Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 5 (STAT5), which translocates to the nucleus and promotes the transcription of GH-responsive genes, including IGF-1.

Chronic exposure to elevated glucocorticoids, a hallmark of the sustained stress response, directly interferes with this pathway. Research indicates that glucocorticoids can induce the expression of suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins. SOCS proteins act as a negative feedback mechanism, binding to activated JAK2 or the GHR itself, thereby attenuating or terminating the signaling cascade. This molecular blockade means that even if GH is present in the circulation, its ability to elicit a cellular response is significantly blunted.

The following table outlines the key molecular components and the impact of chronic stress-induced glucocorticoid excess on their function.

| Component | Normal Function | Impact of Chronic Glucocorticoid Excess | Resulting Physiological Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| GH Receptor (GHR) | Binds circulating GH to initiate intracellular signaling. | Downregulation of GHR expression on cell surfaces. | Reduced tissue sensitivity to GH. |

| JAK2 Kinase | Phosphorylates and activates STAT5 upon GHR activation. | Inhibited by increased expression of SOCS proteins. | Attenuation of the primary GH signaling cascade. |

| STAT5 | Translocates to the nucleus to promote gene transcription. | Reduced phosphorylation and activation due to JAK2 inhibition. | Decreased transcription of target genes like IGF-1. |

| IGF-1 Gene | Transcribed in response to STAT5 activation, producing IGF-1. | Suppressed transcription due to upstream signaling failure. | Lower circulating levels of IGF-1 and reduced anabolic activity. |

What Is the Impact on Cellular Gene Expression?

The influence of chronic stress extends to the epigenetic level. Studies have shown that prolonged stress can alter the gene expression of key components of the somatotropic axis. For instance, research on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in chronically stressed individuals, such as caregivers, found a significant decrease in GH mRNA levels.

This suggests that chronic stress can directly down-regulate the transcription of the GH gene itself within certain cell populations. This finding is particularly relevant as it points to a systemic effect of stress on neuroendocrine gene regulation, extending beyond the pituitary gland. The negative correlation observed between plasma norepinephrine and ACTH levels and GH mRNA further supports the hypothesis that mediators of the stress response actively suppress GH gene expression.

Chronic stress alters the very transcription of the growth hormone gene in immune cells, indicating a deep, systemic reprogramming of the body’s neuroendocrine function.

Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Considerations

This deep-seated, multi-level inhibition of the GH-IGF-1 axis has significant clinical consequences, contributing to the pathophysiology of conditions often associated with chronic stress. These include sarcopenia (age-related muscle loss), increased visceral adiposity, impaired glucose metabolism, and decreased bone mineral density. The state of GH resistance induced by stress mirrors in many ways the metabolic dysfunctions seen in overt GH deficiency.

This understanding informs the rationale behind therapeutic interventions like Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy. Peptides such as Sermorelin, Ipamorelin, and CJC-1295 are not simply replacements for GH. They are secretagogues designed to restore the natural pulsatility of GH release from the pituitary.

By acting on the GHRH receptor, they can help override the somatostatin-dominant inhibitory tone established by chronic stress. The goal of such protocols is to recalibrate the central signaling axis, improve pituitary responsiveness, and ultimately overcome the state of functional GH resistance, thereby restoring the body’s endogenous capacity for repair and metabolic regulation.

References

- Aggarwal, A. & Upadhyay, R. (2013). Neuroendocrine Regulation of Adaptive Mechanisms in Livestock. ResearchGate.

- Fothergill, M. et al. (2022). Understanding the role of growth hormone in situations of metabolic stress. Journal of Neuroendocrinology.

- DeMaso, D. R. & Gold, J. (2021). Stress and Growth in Children and Adolescents. Hormone Research in Paediatrics.

- Jeckel, K. M. et al. (1996). Chronic stress down-regulates growth hormone gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of older adults. Endocrine.

- Green, K. & Stone, M. (2018). The Effect of Acute and Chronic Stress on Growth. ResearchGate.

- Veldhuis, J. D. et al. (2015). Differential impact of age, sex, and body mass index on the quantifiable attributes of the GH-IGF-I axis in adults. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

- Kopchick, J. J. et al. (2020). The role of growth hormone in adipose tissue. Growth Hormone & IGF Research.

- The Endocrine Society. (2019). Clinical Practice Guideline ∞ Evaluation and Treatment of Adult Growth Hormone Deficiency.

- Guyton, A. C. & Hall, J. E. (2020). Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology. Elsevier.

- Boron, W. F. & Boulpaep, E. L. (2016). Medical Physiology. Elsevier.

Reflection

Recalibrating Your Internal Systems

The information presented here provides a biological blueprint for understanding the profound connection between your internal state and your physical vitality. The symptoms you experience are tangible data points, signals from a body navigating a complex environment. The science of endocrinology gives us a language to interpret these signals, moving from a place of concern to a position of informed action.

This knowledge is the foundational step. The path toward optimizing your own biological systems is a personal one, guided by a precise understanding of your unique biochemistry. Your body has an innate capacity for repair and resilience. The journey now involves creating the conditions to unlock that potential.