Fundamentals

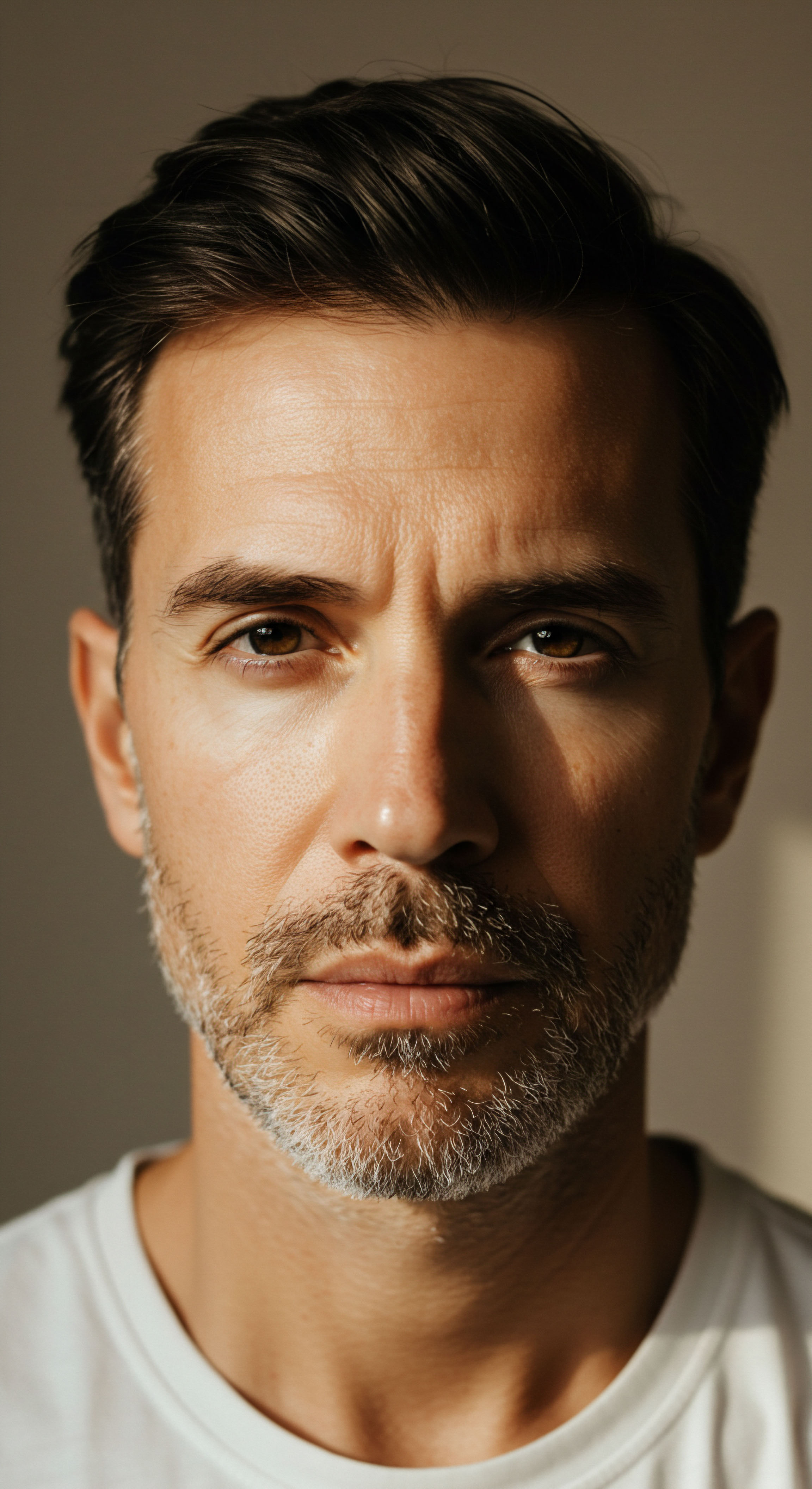

You feel it deep in your bones. A sense of being perpetually drained, of running on a low battery that never seems to fully charge, no matter how much you rest. It is a state of being simultaneously agitated and exhausted, a dissonance that modern life has made profoundly common.

This experience, this lived reality for so many, is where the conversation about hormonal health must begin. Your body is a meticulously orchestrated system of communication, and when one system is shouting, the others must quiet down to listen. Chronic pressure, the unrelenting demand on your physical and mental resources, is that shouting voice.

Its biological name is the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, your body’s command center for managing threats. When this system is perpetually active, it forces another, equally vital system, to take a backseat. This second system is the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, the architect of your reproductive and metabolic vitality.

Understanding this dynamic is the first step toward reclaiming your function. The HPA axis is your survival mechanism. When faced with a stressor ∞ be it a deadline, a difficult conversation, or a poor night’s sleep ∞ your hypothalamus releases a signal, Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH). This tells your pituitary gland to release Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH).

ACTH then travels to your adrenal glands, perched atop your kidneys, and instructs them to produce cortisol. Cortisol is the primary stress hormone. It liberates glucose for immediate energy, heightens your focus, and prepares your body to fight or flee. This is a brilliant, life-saving system for acute situations.

The challenge arises when the “off” switch is never fully engaged. A constant state of alert leads to chronically elevated cortisol, which signals to the body that it is in a state of persistent crisis. In a crisis, long-term projects like reproduction, repair, and robust metabolic health are deemed non-essential luxuries. Survival is the only priority.

The Reproductive Command Chain

Working in parallel is your HPG axis, the system governing reproductive function and a host of other processes that contribute to your sense of vitality. This axis also begins in the hypothalamus, which releases Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) in a pulsatile rhythm.

This rhythmic pulse is like a carefully timed drumbeat that instructs the pituitary gland to produce two other hormones ∞ Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). These gonadotropins then travel to the gonads ∞ the testes in men and the ovaries in women. In men, LH stimulates the Leydig cells in the testes to produce testosterone.

FSH is essential for sperm production. In women, FSH stimulates the growth of ovarian follicles, which in turn produce estrogen. A surge of LH then triggers ovulation and the production of progesterone. These end-products, testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone, are the master regulators of everything from libido and fertility to muscle mass, bone density, mood, and cognitive function.

When Communication Lines Cross

The human body, in its immense wisdom, evolved with a clear hierarchy of needs. Immediate survival, managed by the HPA axis, will always take precedence over long-term procreation, managed by the HPG axis. Chronic pressure creates a biological environment where the HPA axis continuously overrides the HPG axis.

The very hormones that signal “danger” actively suppress the hormones that signal “vitality.” High levels of cortisol send a direct message back to the brain, telling the hypothalamus to slow down its production of GnRH. This disruption of the initial drumbeat means the entire reproductive cascade is muted.

The pituitary produces less LH and FSH, and consequently, the gonads produce less testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone. This is a biological resource allocation decision. The body perceives the environment as too unsafe or resource-scarce to support reproduction, so it diverts its resources toward immediate survival functions powered by cortisol.

The body’s stress response system is designed for acute threats, and its chronic activation systematically downregulates the machinery of reproductive and metabolic health.

This biological competition explains the tangible symptoms you may be experiencing. The fatigue is not just in your mind; it is a consequence of hormonal depletion. The low libido, changes in menstrual cycles, or difficulty building muscle are direct results of the HPA axis suppressing the HPG axis.

It is a physiological reality rooted in the ancient wiring of our nervous and endocrine systems. Recognizing this interconnectedness is profoundly empowering. It reframes your symptoms from personal failings into predictable, biological responses to an unsustainable load. This understanding moves the focus from self-blame to a strategic inquiry ∞ how can we soothe the HPA axis so that the HPG axis can resume its critical work?

The journey begins with appreciating that these two systems are in constant dialogue. Your reproductive health is a direct reflection of your overall stress load. To optimize one, you must manage the other. This foundational concept is the bedrock upon which all effective hormonal wellness protocols are built.

It validates your lived experience by connecting it to the elegant, albeit sometimes challenging, logic of human physiology. Your body is not broken; it is responding exactly as it was designed to. The goal is to change the inputs it receives to foster an internal environment of safety and stability, allowing your innate vitality to come back online.

Intermediate

To truly grasp the impact of chronic pressure on your hormonal landscape, we must move beyond the general overview and examine the specific biochemical mechanisms at play. The suppression of the reproductive system by the stress response is an elegant, multi-pronged process rooted in cellular communication and resource management.

It is a clear demonstration of the body’s prioritization of survival over procreation. When cortisol, the primary effector of the HPA axis, remains elevated, it actively interferes with the HPG axis at every critical juncture, from the brain to the gonads. This interference is a key reason why individuals who are otherwise diligent with diet and exercise may find themselves unable to achieve their health goals, experiencing persistent fatigue, metabolic dysfunction, or reproductive challenges.

The Central Suppression of GnRH

The primary point of control is within the brain, specifically the hypothalamus. The pulsatile release of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) is the master signal for the entire reproductive cascade. Chronic stress disrupts this rhythm with clinical precision. Cortisol, along with the upstream stress hormone CRH, can cross the blood-brain barrier and act directly on the hypothalamus.

They bind to receptors on GnRH-producing neurons, sending a powerful inhibitory signal. This suppression reduces both the frequency and amplitude of GnRH pulses. The carefully timed drumbeat that signals the pituitary to action becomes faint and erratic. Without a consistent GnRH signal, the pituitary gland’s production of Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) diminishes significantly.

This central suppression is the root cause of many stress-induced reproductive issues, from irregular or absent menstrual cycles in women (functional hypothalamic amenorrhea) to lowered testosterone production in men.

What Is the Pregnenolone Steal Phenomenon?

Beyond central suppression, chronic stress initiates a resource allocation problem at the biochemical level. Hormones are not created from thin air; they are synthesized from common precursors. The foundational building block for all steroid hormones, including cortisol, DHEA, testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone, is cholesterol. Cholesterol is converted into a “mother hormone” called pregnenolone.

From here, pregnenolone sits at a crucial crossroads. It can either go down the pathway to produce progesterone and subsequently cortisol (the “survival” pathway), or it can go down the pathway to produce DHEA and subsequently testosterone and estrogen (the “vitality” pathway). Under normal conditions, there is a balanced flow down both paths.

However, under chronic stress, the adrenal glands’ demand for cortisol becomes immense. The body shunts a disproportionate amount of pregnenolone toward the cortisol production line. This diversion is often referred to as the “pregnenolone steal” or “cortisol shunt.” The biochemical machinery prioritizes the manufacturing of stress hormones at the direct expense of reproductive hormones.

This explains why individuals under prolonged pressure often present with high cortisol levels alongside low levels of DHEA, testosterone, and progesterone. It is a clear case of robbing Peter to pay Paul, where “Paul” is the life-or-death demand for cortisol.

Chronic stress biochemically prioritizes cortisol production by diverting the essential hormonal building block, pregnenolone, away from the pathways that create testosterone and estrogen.

This biochemical diversion has profound clinical implications and directly informs targeted therapeutic strategies. When lab testing reveals this pattern ∞ high cortisol paired with suboptimal sex hormones ∞ it provides a clear biological rationale for the symptoms being experienced. It also clarifies why simply adding more testosterone or estrogen might be an incomplete solution. A comprehensive approach must also address the underlying HPA axis dysregulation that is driving the resource diversion in the first place.

Clinical Interventions for Downstream Consequences

When chronic HPA axis activation has led to a quantifiable deficit in reproductive hormones, clinical protocols are designed to restore hormonal balance and function. These interventions are a direct response to the downstream effects of the cortisol-driven suppression of the HPG axis. They aim to re-establish physiological levels of key hormones to alleviate symptoms and improve overall well-being while concurrently addressing the root causes of the stress response.

For many men, the persistent suppression of LH results in a clinical decline in testosterone production, a condition known as secondary hypogonadism. The symptoms extend far beyond low libido, encompassing fatigue, depression, loss of muscle mass, and cognitive fog. A carefully managed Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) protocol can directly address this deficiency.

- Testosterone Cypionate ∞ This is a common form of testosterone administered via intramuscular or subcutaneous injection, typically on a weekly basis. The goal is to restore testosterone levels to an optimal physiological range, alleviating the symptoms of deficiency.

- Gonadorelin ∞ To prevent the testicles from shutting down due to an external source of testosterone, Gonadorelin is often co-administered. It mimics the natural GnRH signal, stimulating the pituitary to continue producing LH, which maintains testicular function and preserves fertility.

- Anastrozole ∞ Testosterone can be converted into estrogen via an enzyme called aromatase. In some men, this conversion can be excessive, leading to side effects. Anastrozole is an aromatase inhibitor used in small doses to manage estrogen levels and maintain a healthy testosterone-to-estrogen ratio.

Women’s hormonal balance is equally, if not more, sensitive to the effects of stress. The disruption of the GnRH pulse can lead to a wide spectrum of issues, from premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and irregular cycles to perimenopausal and post-menopausal symptoms. Stress-induced cortisol production can deplete progesterone and testosterone, leading to anxiety, sleep disturbances, low libido, and fatigue. Tailored hormonal support can be transformative.

- Testosterone Therapy for Women ∞ Women produce and require testosterone for energy, mood, muscle health, and libido. Stress can significantly deplete these already small reserves. Low-dose Testosterone Cypionate, typically administered weekly via subcutaneous injection, can restore vitality and function. Pellet therapy offers a long-acting alternative.

- Progesterone ∞ Often called the “calming” hormone, progesterone is directly impacted by the pregnenolone steal. Supplementing with bio-identical progesterone, particularly in the second half of the menstrual cycle for cycling women or nightly for menopausal women, can dramatically improve sleep quality, reduce anxiety, and balance the effects of estrogen.

The following table illustrates the overlapping symptoms that can arise from both high cortisol (HPA axis activation) and low sex hormones (HPG axis suppression), highlighting the diagnostic challenge and the need for comprehensive evaluation.

| Symptom | Associated with High Cortisol (HPA Activation) | Associated with Low Testosterone (Men & Women) | Associated with Low Estrogen/Progesterone (Women) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue / Low Energy | Present (often “wired but tired”) | Present (persistent exhaustion) | Present |

| Sleep Disturbances | Difficulty falling/staying asleep, waking around 2-4 AM | Poor sleep quality, less restorative sleep | Night sweats, insomnia |

| Mood Changes | Anxiety, irritability, feeling overwhelmed | Depression, apathy, lack of motivation | Anxiety, irritability, mood swings |

| Cognitive Issues | Brain fog, poor memory, difficulty concentrating | Poor focus, mental slowness | Brain fog, memory lapses |

| Changes in Body Composition | Increased abdominal fat, muscle wasting | Decreased muscle mass, increased body fat | Increased body fat, particularly midsection |

| Low Libido | Present | Present | Present |

Understanding these mechanisms shifts the perspective from a collection of disparate symptoms to a logical, interconnected system. It provides a clear roadmap for both diagnosis and treatment, validating the patient’s experience while offering evidence-based protocols to restore function and vitality.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of the interplay between chronic stress and reproductive function requires a systems-biology perspective, moving beyond a simple linear model of HPA-axis dominance. The interaction is a complex, bidirectional feedback loop involving neuroendocrine, metabolic, and immunologic signaling.

The core of this dynamic is the reciprocal antagonism between the glucocorticoid system and the gonadal steroid system, which plays out at the molecular level within the hypothalamus, the pituitary, and the gonads themselves. A deep examination reveals that chronic stress induces a state of “gonadal resistance” through multiple, redundant inhibitory pathways, ensuring the primacy of the survival response.

Molecular Mechanisms of Glucocorticoid-Mediated Suppression

The inhibitory action of glucocorticoids (GCs) on the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis is mediated primarily through genomic and non-genomic actions within the central nervous system. Cortisol, the principal human glucocorticoid, readily crosses the blood-brain barrier and binds to high-affinity mineralocorticoid receptors (MRs) and lower-affinity glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) located densely in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus and in pituitary gonadotroph cells.

Chronic stress, leading to sustained high levels of cortisol, results in persistent GR activation. This activation has several profound consequences for reproductive signaling.

First, GR activation in the hypothalamus directly represses the transcription of the GnRH1 gene, reducing the synthesis of GnRH. This occurs via GRs binding to negative glucocorticoid response elements (nGREs) in the promoter region of the GnRH1 gene. Second, and perhaps more critically, stress signaling powerfully inhibits the activity of the KNDy (kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin) neurons in the arcuate nucleus.

These neurons are the primary drivers of the GnRH pulse generator. Cortisol and CRH suppress the expression of Kiss1, the gene encoding kisspeptin, which is the most potent known stimulator of GnRH release. Simultaneously, stress increases the expression of dynorphin, an opioid peptide that co-localizes in KNDy neurons and potently inhibits GnRH neuron firing. This creates a powerful molecular brake on the entire HPG axis at its very origin.

How Does the Gonadotropin-Inhibitory Hormone Mediate Stress Signals?

Another critical mediator in this process is Gonadotropin-Inhibitory Hormone (GnIH). As its name suggests, GnIH acts as a direct brake on the reproductive axis. Its neurons originate in the dorsomedial hypothalamus and project to GnRH neurons and the pituitary gland. Stress is a powerful stimulus for GnIH synthesis and release.

Glucocorticoids upregulate the transcription of the gene for GnIH. GnIH then acts via its receptor, GPR147, on both GnRH neurons and pituitary gonadotrophs to inhibit their activity. This provides a parallel inhibitory pathway that reinforces the suppressive effects of glucocorticoids, ensuring that the reproductive drive is dampened during periods of perceived threat.

Direct Gonadal and Peripheral Actions

The suppressive influence of chronic stress extends beyond the brain. The adrenal stress hormones, both glucocorticoids and catecholamines (epinephrine and norepinephrine), exert direct inhibitory effects on the gonads. In the testes, glucocorticoid receptors are present on Leydig cells.

High concentrations of cortisol have been shown to inhibit steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein expression and the activity of key enzymes in the testosterone synthesis pathway, such as P450scc and 17α-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase. This directly impairs the ability of the testes to produce testosterone, even in the presence of adequate LH.

In the ovaries, the situation is similarly complex. Stress-induced catecholamines, released from the sympathetic nervous system, can directly affect ovarian follicular development and ovulation. High levels of cortisol can impair granulosa cell function, reducing estrogen and progesterone synthesis and negatively impacting oocyte quality. This creates a state of ovarian resistance to pituitary signals.

In some cases, this can contribute to the development of anovulatory, cystic ovaries, a phenotype seen in conditions like Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), which itself is often exacerbated by stress.

The bidirectional communication between the stress and reproductive axes means that gonadal hormones like testosterone and estradiol also actively modulate HPA axis sensitivity and reactivity.

The relationship is not unidirectional. Gonadal steroids, in turn, modulate HPA axis function. Estradiol, for instance, has been shown to increase the expression of CRH in the hypothalamus and enhance the pituitary’s ACTH response to CRH, potentially contributing to the higher prevalence of stress-related disorders in women.

Testosterone, conversely, generally exerts a dampening effect on the HPA axis, reducing CRH expression and cortisol release. This reciprocal regulation highlights the integrated nature of these systems. The following table provides a detailed summary of the multi-level inhibition of the HPG axis by stress mediators.

| Level of Axis | Mediator | Molecular/Cellular Action | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothalamus | Cortisol / Glucocorticoids | Binds to GRs on GnRH neurons; represses GnRH1 gene transcription. Suppresses Kiss1 expression in KNDy neurons. | Reduced GnRH synthesis and pulse amplitude. |

| Hypothalamus | Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH) | Inhibits GnRH neuronal firing activity. Stimulates GnIH release. | Reduced GnRH pulse frequency. |

| Hypothalamus | Gonadotropin-Inhibitory Hormone (GnIH) | Binds to GPR147 on GnRH neurons, inhibiting their activity. | Direct suppression of the GnRH pulse generator. |

| Pituitary Gland | Cortisol / Glucocorticoids | Binds to GRs on gonadotroph cells, reducing their sensitivity to GnRH. | Blunted LH and FSH release in response to GnRH. |

| Gonads (Testes) | Cortisol / Glucocorticoids | Inhibits StAR protein and key steroidogenic enzymes (e.g. P450scc) in Leydig cells. | Decreased testosterone synthesis. |

| Gonads (Ovaries) | Cortisol & Catecholamines | Impairs granulosa cell function, disrupts follicular development, and can impact oocyte maturation. | Decreased estrogen/progesterone synthesis; anovulation. |

Therapeutic Implications of a Systems Approach

This academic understanding informs a more sophisticated therapeutic strategy. While directly replacing deficient hormones with TRT or other hormonal optimization protocols is effective for managing downstream symptoms, a comprehensive approach also considers upstream interventions. Peptide therapies represent one such advanced strategy. These are small protein chains that can act as highly specific signaling molecules.

For example, peptides like Sermorelin or the combination of Ipamorelin and CJC-1295 are Growth Hormone Releasing Hormone (GHRH) analogs or secretagogues. They stimulate the body’s own production of Growth Hormone (GH), another pituitary hormone that is often suppressed by chronic stress.

Restoring a healthy GH axis can have positive cascading effects on metabolism, tissue repair, and overall systemic balance, which can, in turn, help buffer the HPA axis and support HPG function. This represents a move toward restoring the body’s own regulatory systems, a core principle of advanced longevity and wellness science.

References

- Whirledge, S. & Cidlowski, J. A. (2017). Stress and the HPA Axis ∞ Balancing Homeostasis and Fertility. International journal of molecular sciences, 18(10), 2223.

- Gour, D. S. Kuncha, M. Kumar, A. & Singh, D. (2024). Impact of chronic stress on reproductive functions in animals. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology, 15(1), 78.

- Joseph, C. N. & Whirledge, S. (2017). Stress and the HPA Axis ∞ Balancing Homeostasis and Fertility. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 18(10), 2223.

- Lee, S. (2025). Managing Stress for Fertility Success. Number Analytics.

- Blake, A. (2022). Stress and the HPA Axis ∞ Balancing Homeostasis and Fertility. FACTS (Fertility Appreciation Collaborative to Teach the Science).

Reflection

Charting Your Biological Course

You have now journeyed through the intricate biological pathways that connect the pressure you feel in your daily life to the very core of your cellular function. This knowledge is more than an academic exercise; it is a form of self-awareness.

It provides a new lens through which to view your own body, transforming feelings of frustration or exhaustion into a clear, physiological narrative. You can now recognize the dialogue between your survival systems and your vitality systems. You understand that your body is making logical, albeit sometimes detrimental, choices based on the signals it receives from your environment and your internal state.

This understanding is the starting point. It equips you to ask more precise questions and to seek solutions that honor the complexity of your own unique biology. The path toward recalibrating these systems is deeply personal. It involves a careful examination of the inputs you can control and a strategic plan to support the systems that have been compromised.

The information presented here is a map, but you are the cartographer of your own health journey. The ultimate goal is to create an internal environment where your body no longer feels the need to shout for survival, allowing the powerful, quiet work of thriving to resume.

Glossary

chronic pressure

pituitary gland

hpa axis

cortisol

hpg axis

carefully timed drumbeat that

low libido

stress response

chronic stress

pregnenolone steal

testosterone replacement therapy

secondary hypogonadism

gonadorelin

anastrozole

gnrh pulse

glucocorticoid receptors

kisspeptin

gonadotropin-inhibitory hormone

gnrh neurons

estrogen and progesterone