Fundamentals

You feel it in your bones, a deep exhaustion that sleep does not seem to touch. There is a persistent sense of running on an empty tank, a feeling of being simultaneously agitated and depleted. This lived experience, this sensation of being perpetually “on” while also being profoundly tired, is a tangible signal from your body.

It is the language of your internal systems responding to a relentless demand. Your body is communicating a state of profound imbalance, one that originates deep within the command center of your stress response. Understanding this biological conversation is the first step toward reclaiming your vitality.

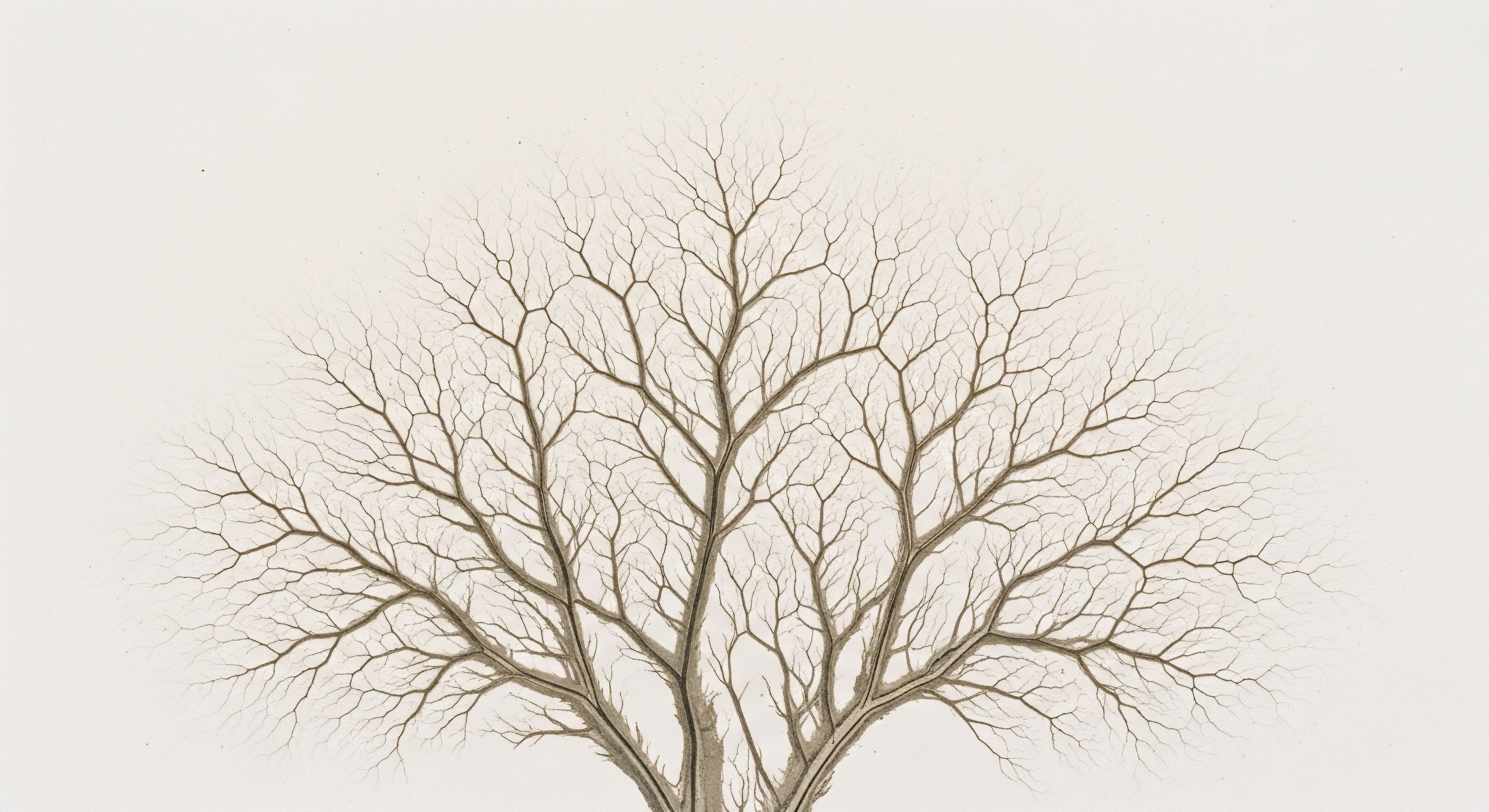

At the heart of this response is a sophisticated and ancient system known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. Think of it as your body’s internal emergency broadcast system, a network connecting your brain to your adrenal glands.

When your brain perceives a threat ∞ be it a demanding workout, a looming deadline, or a lack of sleep ∞ the hypothalamus sends a signal to the pituitary gland. The pituitary, in turn, signals the adrenal glands, which then release a cascade of hormones. The most prominent of these is cortisol.

The Role of the Primary Action Hormone

Cortisol is your primary action hormone, designed for short-term, high-stakes situations. Its purpose is to ensure survival. When released, it rapidly mobilizes energy, increasing blood sugar to fuel your muscles and sharpen your focus. It prepares your body to fight or flee. In acute situations, this system is remarkably effective.

The stressor appears, cortisol surges, you handle the situation, and then the system powers down through a negative feedback loop. Cortisol itself signals the hypothalamus to stop the alarm, bringing the body back to a state of balance, or homeostasis.

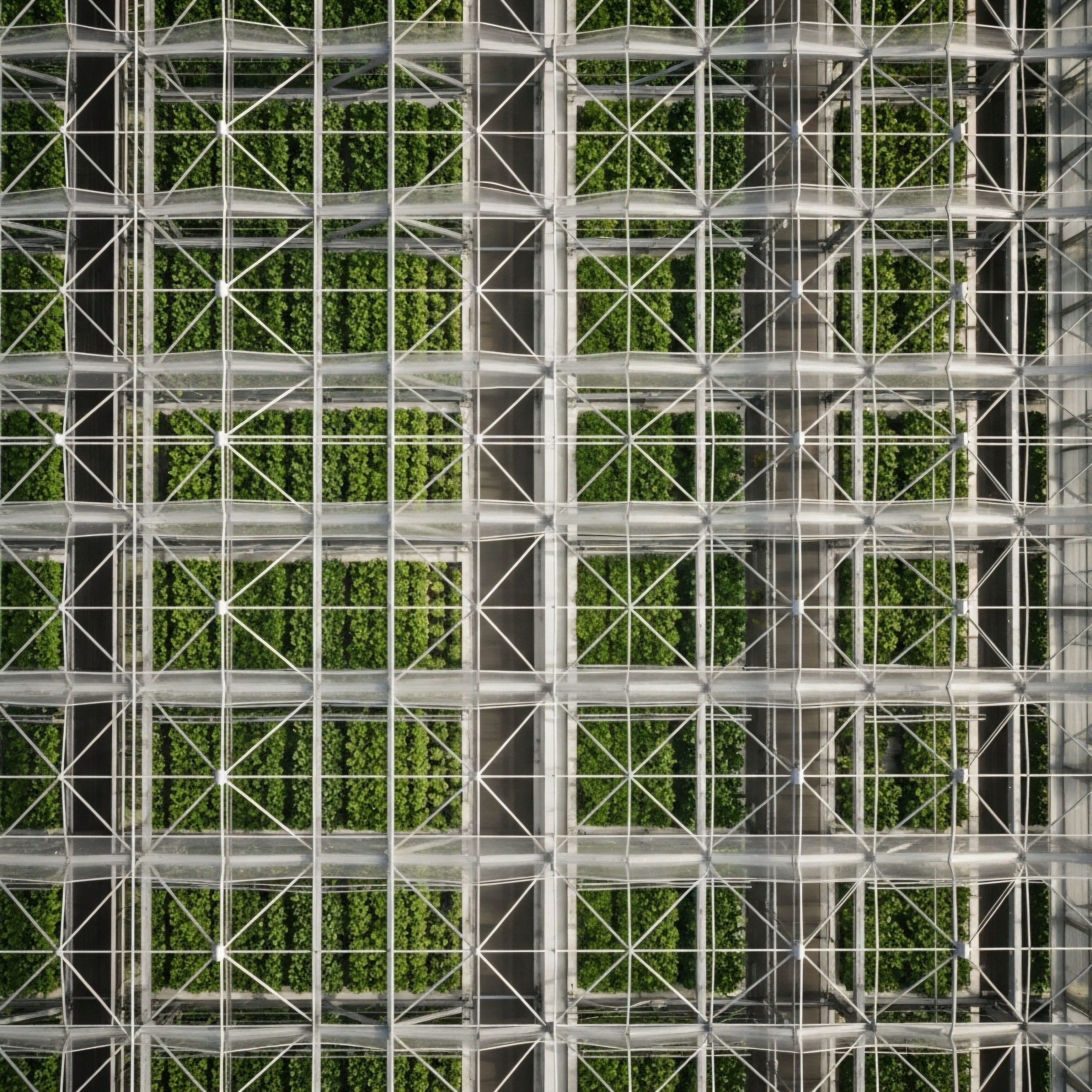

This elegant design works perfectly for the intermittent threats our ancestors faced. The challenge of modern life, and particularly of sustained physical demand, is the chronic nature of the stressors. The alarm system is triggered not just once a day, but continuously. The emergency broadcast never quite shuts off. This constant activation transforms a life-saving mechanism into a source of systemic disruption.

When the Stress Switch Remains On

When your body is subjected to unending physical stress, such as intense athletic training without adequate recovery, chronic pain, or grueling physical labor, the HPA axis remains in a state of high alert. Initially, this results in consistently elevated cortisol levels. Your body is perpetually mobilizing resources for a threat that never fully recedes.

This sustained output of cortisol begins to have far-reaching consequences. The systems that were temporarily paused for the “emergency” ∞ like digestion, immune surveillance, and reproductive function ∞ are now chronically suppressed. The body’s resources are continuously diverted towards managing the perceived crisis.

Chronic physical stress forces the body’s survival system into a state of continuous operation, fundamentally altering its internal hormonal environment.

This is where the feeling of being “wired and tired” comes from. The high cortisol keeps your nervous system in a state of arousal, making it difficult to relax or sleep deeply. Simultaneously, the immense energy expenditure required to maintain this state of alert leads to profound fatigue. Your body is burning through its reserves at an unsustainable rate.

A System of Interconnected Pathways

The endocrine system is a web of communication. Hormones are chemical messengers, and their signals are intricately linked. The HPA axis does not operate in a vacuum. Its constant activation directly impacts other critical hormonal systems. The body, in its wisdom, operates on a hierarchy of needs. When survival is the top priority, other long-term projects like metabolic regulation, reproduction, and tissue repair are deprioritized.

The sustained demand for cortisol production places a heavy tax on the body’s resources. This directly affects the thyroid gland, which governs your metabolism, and the gonads, which produce sex hormones like testosterone and estrogen. The body begins to make a biological choice, diverting raw materials away from these systems to fuel the unceasing stress response.

This begins a cascade of hormonal imbalances that extend far beyond the HPA axis, touching every aspect of your health and well-being. The fatigue, the mood changes, the metabolic shifts ∞ they are all downstream effects of this fundamental disruption.

Intermediate

The persistent feeling of exhaustion from chronic physical stress is more than just a subjective experience; it is the clinical manifestation of a measurable biological burden. This cumulative wear and tear is defined by the concept of allostatic load. Allostasis is the process of achieving stability, or homeostasis, through physiological change.

When the demands on the body are relentless, the systems responsible for adaptation become overworked, leading to allostatic overload. Think of it as the mounting debt on a credit card used to fund a perpetual state of emergency. The initial credit line (your body’s resilience) is generous, but eventually, the interest payments in the form of physiological damage become overwhelming.

The primary system bearing this load is the HPA axis. Its journey from a healthy, responsive network to a dysregulated, exhausted one can be understood as a progression through distinct stages. Recognizing these stages is essential for understanding where you are in this process and how to begin recalibrating your system.

The Stages of HPA Axis Dysregulation

The body’s response to chronic stress is a dynamic process. It attempts to adapt, but these adaptations come at a cost, leading to a predictable pattern of dysfunction over time.

Stage 1 the Alarm Reaction

This is the initial response to a persistent stressor. Your body perceives a continuous threat and ramps up HPA axis activity. During this stage, cortisol levels are consistently elevated. You might feel a surge of energy, albeit a tense, anxious one. Sleep may become difficult, and you might rely on stimulants to get through the day. While performance might initially increase, this state is metabolically expensive and is the first step towards imbalance.

Stage 2 the Resistance Response

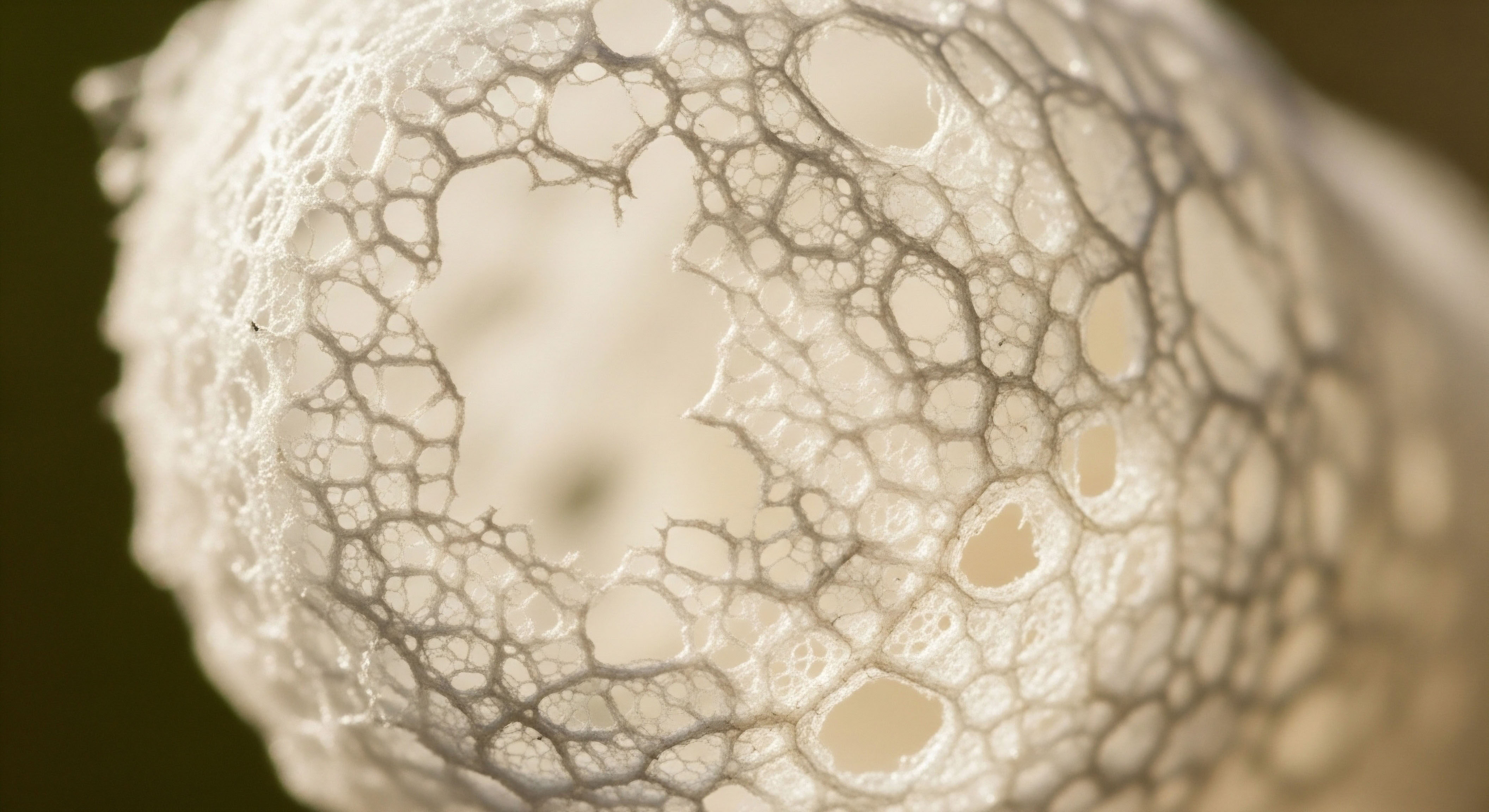

After weeks or months of high alert, the body begins to adapt. The cells of your body, bombarded by cortisol, start to become less sensitive to its signals. This phenomenon is known as glucocorticoid receptor (GR) resistance. Your brain and immune cells effectively turn down the volume on cortisol’s message.

The HPA axis, sensing that its signals are not being heard, may even work harder, pushing out more cortisol to compensate. This creates a paradoxical situation ∞ cortisol levels in the blood can be high, but the hormone is unable to perform its functions effectively, particularly its crucial role in regulating inflammation. This leads to a state of underlying, unmanaged inflammation, which can manifest as aches, pains, and an increased susceptibility to illness.

Stage 3 the Exhaustion Phase

Following a prolonged period of resistance and overwork, the HPA axis may begin to lose its capacity to respond. The intricate machinery involved in producing stress hormones can become depleted. This can lead to a state of hypocortisolism, or low cortisol output.

The total amount of cortisol produced over a day may be low, and the normal daily rhythm ∞ high in the morning, tapering off at night ∞ becomes flattened. This stage is synonymous with burnout. It is characterized by profound fatigue, low blood pressure, an inability to handle even minor stressors, and often, widespread pain and cognitive fog.

| Stage | Primary Characteristic | Typical Cortisol Pattern | Common Subjective Experience |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 ∞ Alarm | Initial hyper-stimulation of the HPA axis. | Consistently high cortisol levels. | Feeling “wired,” anxious, and having difficulty with sleep. |

| Stage 2 ∞ Resistance | Development of glucocorticoid receptor resistance. | High or fluctuating cortisol; loss of cellular sensitivity. | Feeling tired but still pushing through; emergence of inflammatory symptoms. |

| Stage 3 ∞ Exhaustion | Reduced HPA axis output and resilience. | Low overall cortisol production; blunted daily rhythm. | Profound fatigue, burnout, poor recovery, and low resilience. |

The Domino Effect on the Endocrine System

The dysregulation of the HPA axis initiates a cascade of effects that disrupt the entire endocrine system. The body’s prioritization of cortisol production comes at the direct expense of other vital hormonal pathways.

How Does Stress Impact Thyroid Function?

Your thyroid gland acts as the accelerator pedal for your metabolism. The HPA axis has a direct, suppressive effect on thyroid function in several ways:

- Impaired T4 to T3 Conversion ∞ Your thyroid produces mostly thyroxine (T4), an inactive storage hormone. For your body to use it, it must be converted into triiodothyronine (T3), the active metabolic hormone. High cortisol levels inhibit the enzyme responsible for this conversion.

- Increased Reverse T3 (rT3) ∞ Under stress, the body shunts T4 conversion down an alternative pathway, producing more reverse T3 (rT3). rT3 is an inactive molecule that fits into the T3 receptor site, effectively blocking the active hormone from doing its job. This is like putting the wrong key in a lock; it does not open the door and prevents the right key from being used.

- Suppressed Pituitary Signaling ∞ High cortisol can also suppress the pituitary’s release of Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH), reducing the overall signal for the thyroid to produce hormones.

The result is cellular hypothyroidism. Your standard lab tests for TSH and T4 might appear normal, yet you experience all the symptoms of an underactive thyroid ∞ fatigue, weight gain, hair loss, and feeling cold. Your metabolism has been intentionally slowed down by the body as a survival strategy.

Your body interprets chronic stress as a famine, slowing your metabolism via thyroid suppression to conserve energy for survival.

The Pregnenolone Steal and Sex Hormones

Hormone production is a matter of shared resources. The body uses a foundational molecule, pregnenolone, as the raw material to create both cortisol and sex hormones like DHEA, testosterone, and estrogen. This shared pathway is called the steroid hormone cascade. When the demand for cortisol is chronically high, the body diverts pregnenolone away from the pathways that produce sex hormones and shunts it towards cortisol production. This is often referred to as “pregnenolone steal” or “cortisol steal.”

For men, this leads to a decline in DHEA and testosterone. This manifests as low libido, reduced muscle mass, fatigue, and diminished motivation. The testosterone-to-cortisol ratio, a key marker in sports medicine, plummets, indicating a shift from an anabolic (building) state to a catabolic (breaking down) state.

For women, the consequences are equally significant. The disruption of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis can lead to irregular menstrual cycles, worsening PMS symptoms, and an earlier or more severe presentation of perimenopause. The delicate balance between estrogen and progesterone is disrupted, contributing to mood swings, fatigue, and other symptoms associated with hormonal imbalance.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of chronic physical stress on endocrine function requires moving beyond systemic observation into the molecular mechanics of cellular communication and resistance. The clinical presentation of fatigue, metabolic disturbance, and hypogonadism is the macroscopic result of microscopic changes in receptor sensitivity, gene transcription, and intercellular signaling.

The central lesion in this process is the progressive failure of glucocorticoid signaling, a state of acquired hormone resistance that precipitates a cascade of neuro-endocrine-immune dysregulation. This section explores the molecular underpinnings of this phenomenon, using overtraining syndrome (OTS) as a precise human model of chronic physical stress.

Molecular Mechanisms of Glucocorticoid Receptor Resistance

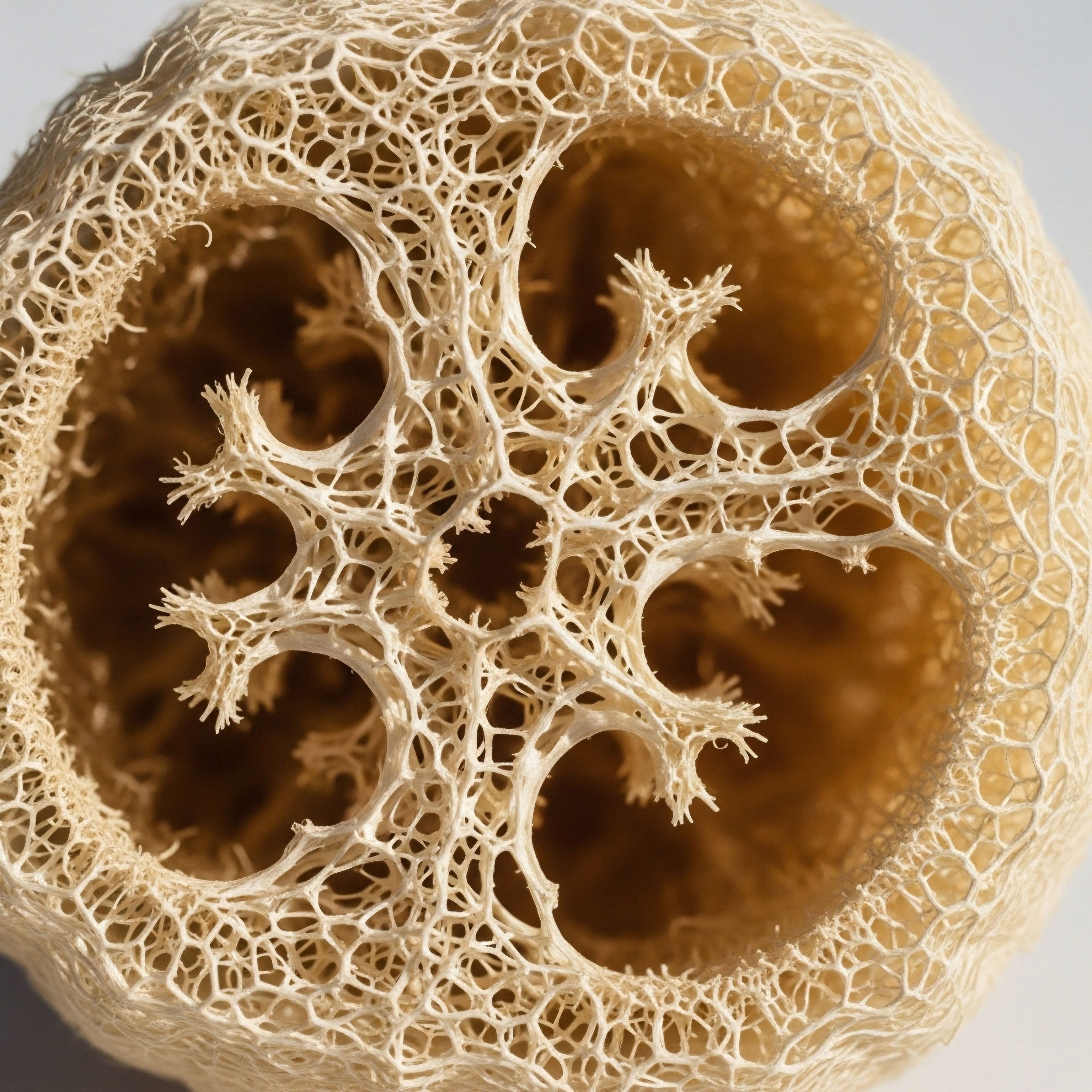

The biological impact of cortisol is mediated by the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), an intracellular protein that, upon binding to cortisol, translocates to the nucleus to act as a ligand-dependent transcription factor. It modulates the expression of thousands of genes. Glucocorticoid resistance (GCR) is a state where target tissues lose their sensitivity to cortisol, a condition precipitated by chronic exposure to the hormone.

GR Isoforms and Post-Translational Modifications

The human GR gene (NR3C1) gives rise to multiple isoforms through alternative splicing and translation initiation. The primary active isoform is GRα, which binds cortisol and mediates its effects. Another key isoform, GRβ, does not bind cortisol and acts as a dominant negative inhibitor of GRα.

Chronic inflammatory states, often driven by stress, can increase the expression of GRβ, shifting the GRα/GRβ ratio and inducing a state of localized hormone resistance. This mechanism allows inflammation to persist even in the presence of high circulating cortisol.

Furthermore, the function of GRα is finely tuned by post-translational modifications, particularly phosphorylation. Stress-activated signaling cascades, such as the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, can phosphorylate the GR at specific sites. This phosphorylation can alter the receptor’s stability, its ability to bind DNA, and its interaction with co-regulatory proteins, ultimately diminishing its capacity to regulate gene expression and suppress inflammation effectively.

The Neuro-Endocrine-Immune Feedback Loop

The relationship between stress, cortisol, and the immune system is bidirectional. Chronic stress activates the sympathetic nervous system and the HPA axis, leading to the release of catecholamines and glucocorticoids. These mediators are intended to modulate the immune response. However, a state of chronic stress and the resultant GCR disrupt this regulatory function.

The immune system, failing to receive cortisol’s anti-inflammatory signal, becomes dysregulated. Activated immune cells, such as macrophages and lymphocytes, produce pro-inflammatory cytokines, including Interleukin-1β (IL-1β), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), and Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α).

These cytokines, in turn, signal back to the central nervous system. They can cross the blood-brain barrier or signal via afferent nerves to stimulate the HPA axis further, creating a pathological positive feedback loop. Cytokines directly promote GCR in peripheral tissues and the brain, perpetuating a state of low-grade, systemic inflammation.

This inflammation is a key driver of the symptoms associated with chronic stress, including fatigue, pain, and mood disturbances, and is implicated in the pathophysiology of numerous chronic diseases.

Glucocorticoid receptor resistance severs the communication line between the stress axis and the immune system, fostering a self-perpetuating cycle of inflammation.

Overtraining Syndrome a Human Model of Allostatic Overload

Overtraining syndrome (OTS) provides a powerful clinical model for examining the effects of excessive physical stress on the human endocrine system. OTS is a state of prolonged maladaptation resulting from an imbalance between intense training and inadequate recovery. It represents a progression to the exhaustion phase of HPA axis dysregulation.

What are the key hormonal shifts in overtrained athletes? The hormonal profile of an overtrained athlete is complex and reveals the depth of the systemic disruption. While early stages of overreaching may show elevated cortisol, established OTS often presents with a blunted neuroendocrine response.

- Blunted Pituitary Response ∞ When subjected to a standardized exercise stress test, athletes with OTS often show a diminished release of Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH) and Growth Hormone (GH) from the pituitary gland. This indicates a desensitization or exhaustion at the central level of the stress axis.

- Altered Cortisol Profile ∞ Basal cortisol levels can be variable, sometimes even lower than in healthy athletes, reflecting adrenal hypo-responsiveness. The diurnal rhythm is typically flattened, with a less pronounced morning peak. The cortisol response to acute exercise is also blunted.

- Suppressed Gonadal Axis ∞ The testosterone-to-cortisol ratio is a widely used marker of training stress. In overtrained male athletes, this ratio is significantly decreased, reflecting both suppressed testosterone production and altered cortisol dynamics. This indicates a profound shift toward a catabolic state.

- Immune and Inflammatory Markers ∞ OTS is associated with evidence of systemic inflammation and immune suppression, including elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and a greater susceptibility to infections, consistent with the consequences of GCR.

| Hormonal Axis | Observed Change in OTS | Underlying Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) | Blunted ACTH and cortisol response to stimulation. Altered diurnal cortisol rhythm. | Central fatigue of the axis; receptor desensitization; potential adrenal hypo-responsiveness. |

| Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) | Decreased basal testosterone. Reduced testosterone-to-cortisol ratio. | Suppression of GnRH by stress mediators; resource diversion (“pregnenolone steal”). |

| Somatotropic (Growth Hormone) | Blunted GH secretion in response to exercise. Reduced IGF-1 levels. | Dysregulation of hypothalamic GHRH/somatostatin; peripheral resistance to GH. |

| Immune System | Elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-6, TNF-α). Increased susceptibility to illness. | Glucocorticoid receptor resistance; failure to contain inflammation. |

Systemic Consequences of Endocrine Exhaustion

The hormonal collapse seen in OTS has profound systemic effects. The catabolic state leads to muscle wasting and prevents effective tissue repair. Mitochondrial dysfunction, driven by excess oxidative stress and insufficient hormonal support, impairs cellular energy production, explaining the deep, pervasive fatigue.

In the brain, altered glucocorticoid signaling and elevated cytokines disrupt neurotransmitter systems, affecting mood, motivation, and cognitive function. The syndrome is a holistic failure of the body’s adaptive systems, a clear demonstration that chronic physical stress, when unchecked, can dismantle the very hormonal architecture that supports life and function.

References

- Herman, James P. et al. “Regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical stress response.” Comprehensive Physiology, vol. 6, no. 2, 2016, pp. 603-621.

- Cohen, Sheldon, et al. “Chronic stress, glucocorticoid receptor resistance, inflammation, and disease risk.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 109, no. 16, 2012, pp. 5995-5999.

- McEwen, Bruce S. “Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation ∞ central role of the brain.” Physiological reviews, vol. 87, no. 3, 2007, pp. 873-904.

- Farrow, M. and S. L. G. G. F. A. O’Connor. “Hormonal aspects of overtraining syndrome ∞ a systematic review.” Sports Medicine, vol. 47, no. 11, 2017, pp. 2279-2296.

- Urhausen, A. H. Gabriel, and W. Kindermann. “Blood hormones as markers of training stress and overtraining.” Sports Medicine, vol. 20, no. 4, 1995, pp. 251-276.

- Fava, Giovanni A. et al. “Allostatic Load and Endocrine Disorders.” Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, vol. 92, no. 3, 2023, pp. 162-169.

- Pariante, Carmine M. and Andrew H. Miller. “Glucocorticoid receptors in major depression ∞ relevance to pathophysiology and treatment.” Biological Psychiatry, vol. 49, no. 5, 2001, pp. 391-404.

- Helmreich, Dana L. et al. “Chronic variable stress alters hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in the female mouse.” Physiology & Behavior, vol. 210, 2019, p. 112651.

- Walter, K. N. et al. “Elevated thyroid stimulating hormone is associated with elevated cortisol in healthy young men and women.” Thyroid Research, vol. 5, no. 1, 2012, p. 13.

- Picard, Martin, and Bruce S. McEwen. “Psychological Stress and Mitochondria ∞ A Conceptual Framework.” Psychosomatic Medicine, vol. 80, no. 2, 2018, pp. 126-140.

Reflection

You have now traveled from the felt sense of exhaustion to the intricate molecular dance that governs your body’s response to stress. This knowledge provides a framework, a new language to understand the signals your body has been sending. It transforms abstract feelings of fatigue and distress into a coherent biological narrative. This understanding is the essential foundation upon which a path to recovery is built.

The journey of hormonal recalibration is deeply personal. While the biological principles are universal, your specific history, genetics, and lifestyle create a unique physiological landscape. The information presented here is a map of the territory. The next step involves locating your precise position on that map. This requires a thoughtful assessment, a partnership to translate these concepts into a personalized protocol that addresses the root causes of your body’s imbalance.

Consider this knowledge not as a diagnosis, but as an empowerment. It is the tool that allows you to move from a passive experience of symptoms to a proactive engagement with your own health. The potential to restore your body’s intricate communication network, to reclaim your energy and function, lies within this informed approach. Your vitality is not lost; it is simply waiting for the right conditions to be restored.

Glossary

cortisol

cortisol levels

hpa axis

endocrine system

cortisol production

sex hormones

chronic physical stress

allostatic load

chronic stress

glucocorticoid receptor

hypocortisolism

reverse t3

cellular hypothyroidism

pregnenolone steal

overtraining syndrome

immune system