Fundamentals

You may be noticing a subtle shift in your cognitive function, a certain fogginess in your thinking or a frustrating delay in recalling information. When you are undergoing or have recently completed a treatment involving a Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) agonist, this experience is a valid and recognized biological reality.

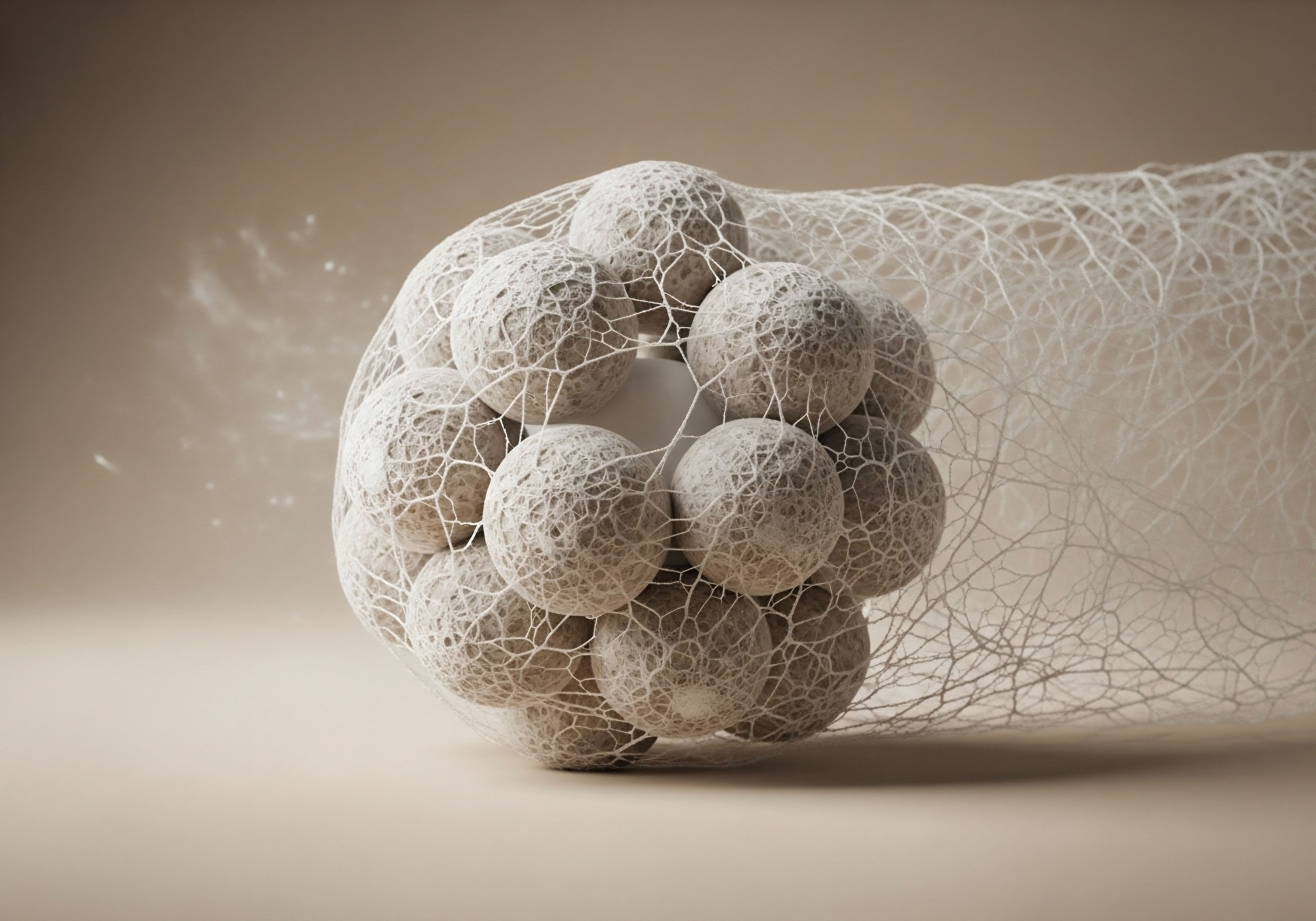

Your body’s internal communication network, a sophisticated system known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, has been deliberately and temporarily quieted. This axis functions as the central command for your reproductive and hormonal health, with GnRH itself acting as the master signal that initiates a cascade of messages.

Think of the HPG axis as an intricate hormonal orchestra. The hypothalamus, a small region at the base of your brain, acts as the conductor, sending out GnRH like a rhythmic beat. This beat instructs the pituitary gland, the orchestra’s lead musician, to release other hormones, primarily Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH).

These hormones, in turn, travel through the bloodstream to the gonads ∞ the testes in men and the ovaries in women ∞ prompting them to produce the primary sex hormones ∞ testosterone and estrogen. These sex hormones are powerful molecules that influence everything from physical characteristics to mood, energy, and, critically, cognitive sharpness.

The use of a GnRH agonist intentionally pauses the body’s natural production of sex hormones, which are integral to maintaining cognitive clarity and function.

A GnRH agonist introduces a continuous, monotonous signal that overrides the natural, rhythmic pulse of GnRH. This steady signal effectively desensitizes the pituitary gland. The orchestra’s lead musician, confused by the lack of a clear beat, stops playing. Consequently, the production of LH and FSH dwindles, and the gonads fall silent, ceasing the production of testosterone and estrogen.

This induced state of hormonal suppression is the therapeutic goal for conditions like prostate cancer, endometriosis, or precocious puberty. It also creates a direct impact on the brain, an organ rich with receptors for these very hormones.

The process of cognitive recovery after discontinuing the agonist hinges on how readily this hormonal orchestra can reassemble and begin playing in harmony again. The age at which the treatment occurs is a defining factor in the speed and completeness of this restoration. The brain’s own resilience, its structural and chemical environment at the time of treatment, dictates its capacity to rebound from this period of induced hormonal silence.

Intermediate

Understanding why age is such a significant variable in cognitive recovery requires a deeper look into the brain’s dynamic relationship with sex hormones. This relationship is not static; it evolves throughout life. The brain possesses what are often termed “critical windows,” periods during which it is uniquely sensitive to the organizational and activational effects of hormones like estrogen and testosterone.

The age at which GnRH agonist therapy is introduced determines which of these windows is affected, directly influencing the potential for cognitive rebound after treatment.

The Developing Brain versus the Mature Brain

When GnRH agonist therapy is administered during adolescence, for instance to manage precocious puberty, it occurs while the brain is undergoing a profound period of development and synaptic pruning. Animal models suggest that interrupting the gonadal hormone surge during this peri-pubertal window can lead to lasting changes in brain structure and emotional regulation.

The cognitive system is still being wired, and while it possesses immense plasticity, altering the hormonal signals that guide this wiring process can have long-term implications. Recovery in this younger group depends on the HPG axis’s ability to robustly reactivate and complete these developmental processes once the agonist is discontinued.

The Critical Window for Hormonal Influence

In adult women, particularly those treated for conditions like endometriosis or fibroids during their reproductive years, the brain has long been accustomed to the cyclical presence of estrogen. Estrogen is a key supporter of neural health, particularly in brain regions vital for verbal memory and executive function, like the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex.

Studies on hormone therapy in menopausal women show that the timing of hormonal intervention is paramount. Initiating estrogen therapy close to the onset of menopause appears to protect cognitive function, whereas starting it years later has little benefit and may even pose risks.

When a GnRH agonist induces a temporary, reversible menopause, the age of the patient places her at a specific point on this sensitivity curve. A younger woman’s brain may be more resilient and responsive to the return of estrogen, while an older woman approaching natural menopause may find her cognitive baseline resets to a lower level post-treatment.

The brain’s sensitivity to hormones changes over a lifetime, meaning the age at treatment determines the specific nature of the cognitive impact and the potential for recovery.

Testosterone Deprivation and Cognitive Resilience in Men

For older men undergoing androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for prostate cancer, often with GnRH agonists, the scenario is different yet again. These men are typically treated at an age when a natural decline in testosterone and cognitive function is already occurring. The profound suppression of testosterone induced by ADT can accelerate these changes.

Research clearly links delayed testosterone recovery after discontinuing treatment with a higher incidence of depression and persistent cognitive dysfunction. An older man’s HPG axis is often less robust, and the recovery of testosterone production can be sluggish or incomplete. This prolonged period of hypogonadism leaves the aging brain vulnerable, potentially making some cognitive changes less reversible.

The following table outlines the primary applications of GnRH agonists across different life stages and the corresponding hormonal goals.

| Condition | Typical Age Group | Primary Hormonal Target | Primary Cognitive Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central Precocious Puberty | Childhood / Early Adolescence | Suppress Estrogen & Testosterone | Impact on a brain undergoing active development and wiring. |

| Endometriosis / Uterine Fibroids | Reproductive Years (20s-40s) | Suppress Estrogen | Interruption of established estrogen-dependent cognitive pathways. |

| Prostate Cancer (ADT) | Middle to Older Adulthood (50+) | Suppress Testosterone | Exacerbation of age-related cognitive decline due to severe hypogonadism. |

The cognitive functions most commonly affected by the suppression of these hormones include:

- Verbal Memory ∞ The ability to recall words and spoken information, which is strongly supported by estrogen.

- Executive Functions ∞ Skills like planning, organizing, and multitasking, which are modulated by both estrogen and testosterone in the prefrontal cortex.

- Processing Speed ∞ The rate at which the brain can take in and respond to information.

- Spatial Orientation ∞ The capacity to understand and navigate one’s environment, a function where sex-specific differences have been noted.

Academic

A molecular and systems-level analysis reveals that age-related differences in cognitive recovery post-GnRH agonist treatment are rooted in the fundamental biology of neuroplasticity and the variable resilience of the HPG axis. The brain is not a static organ; its ability to adapt, remodel, and repair itself declines with age. This age-dependent decline in plasticity is a central factor determining the cognitive outcome following a period of profound, chemically induced hormonal suppression.

Neuroplasticity and the Age-Dependent Response

The adolescent brain is characterized by a high degree of structural and synaptic plasticity. It is actively forming and eliminating connections in response to environmental and endocrine cues. While this makes it vulnerable to the organizational disruption caused by peri-pubertal GnRH agonist treatment, its inherent adaptability may also facilitate a more complete functional recovery once hormonal signaling is restored.

In contrast, the adult and, particularly, the aging brain exhibits significantly reduced neuroplasticity. The capacity for neurogenesis (the birth of new neurons), synaptogenesis (the formation of new synapses), and dendritic arborization is diminished. When an older individual undergoes hormonal suppression, their brain has less intrinsic capacity to compensate for the withdrawal of neurotrophic support provided by sex hormones. The recovery trajectory is therefore shallower, and the risk of a permanent downward shift in the cognitive baseline is elevated.

What Cellular Mechanisms Underlie Hormonal Action and Withdrawal?

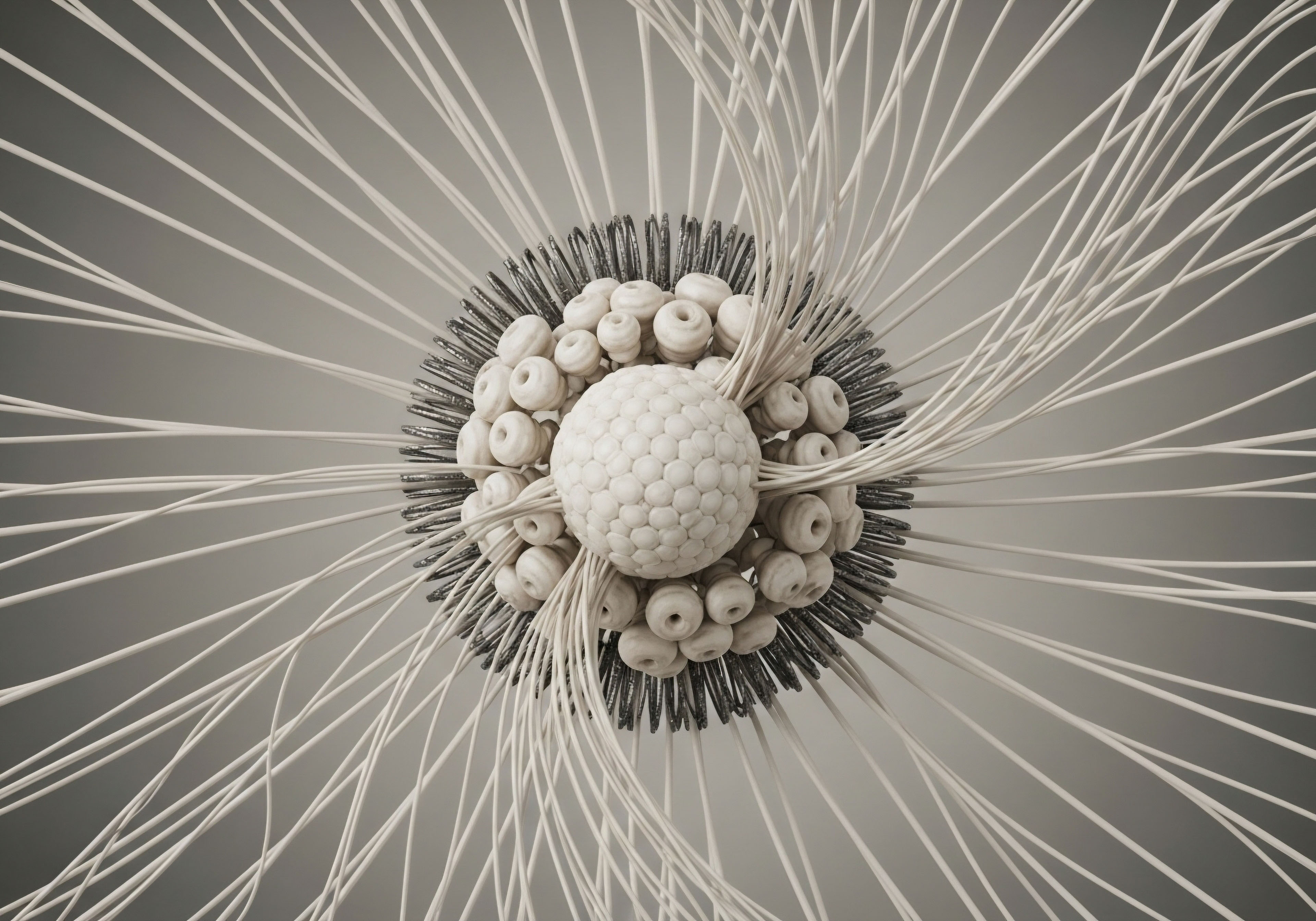

Estrogen and testosterone exert powerful effects at the cellular level. They are not merely signaling molecules but active modulators of brain structure and function. They influence the synthesis and activity of key neurotransmitter systems, including acetylcholine (critical for memory), dopamine (essential for executive function and motivation), and serotonin (a key regulator of mood).

Furthermore, these hormones promote the expression of neurotrophic factors like Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), which supports neuron survival and growth. The withdrawal of these signals via a GnRH agonist initiates a cascade of downstream effects.

It can reduce synaptic density, impair long-term potentiation (the cellular basis of learning and memory), and potentially increase the brain’s vulnerability to inflammatory processes and oxidative stress. In an older brain, which may already have subclinical levels of inflammation or vascular compromise, this hormonal withdrawal can push the system past a critical threshold from which full recovery is difficult.

The brain’s structural and chemical resilience to hormonal suppression diminishes with age, making older individuals more susceptible to lasting cognitive changes.

What Determines the Pace of HPG Axis Reactivation?

The speed and completeness of HPG axis recovery after treatment cessation are highly age-dependent. In a young person, the hypothalamic GnRH pulse generator and the pituitary and gonadal cells are robust and highly responsive. Upon removal of the agonist’s suppressive signal, the system typically reawakens with vigor.

In an older male patient treated for prostate cancer, the situation is markedly different. The Leydig cells in the testes may have become atrophic after a prolonged period of dormancy. The hypothalamic-pituitary signaling may be less dynamic.

Consequently, testosterone recovery can be significantly delayed, taking many months or even years, and in some cases, it may never return to baseline levels. This extended period of hypogonadism constitutes a state of chronic hormonal deprivation for the brain, compounding any initial cognitive impact.

The neurological influence of estrogen and testosterone, while overlapping, have distinct characteristics.

| Hormone | Primary Neurological Sphere of Influence | Effect of Deprivation |

|---|---|---|

| Estrogen | Supports cholinergic system (memory), promotes serotonin activity (mood), increases synaptic density in the hippocampus. | Leads to declines in verbal memory and processing speed, mood instability. |

| Testosterone | Modulates dopaminergic pathways (executive function, motivation), supports myelination, has neuroprotective effects. | Contributes to depression, fatigue, and deficits in executive function and spatial reasoning. |

References

- Asthana, Sanjay, et al. “Cognitive effects of hormone therapy continuation or discontinuation in a sample of women at risk for Alzheimer’s disease.” Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, vol. 8, 2016, p. 223.

- Henderson, Victor W. “Cognitive Changes After Menopause ∞ Influence of Estrogen.” Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, vol. 51, no. 3, 2008, pp. 618-26.

- Evans, N. P. et al. “Effects of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist on brain development and aging ∞ results from two animal models.” Norwegian University of Life Sciences, 2013.

- “Delayed Testosterone Recovery After Prostate Cancer Treatment ∞ Understanding Risks and Clinical Implications.” Nice Order Now, 18 July 2025.

- “Depression (mood).” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 2024.

Reflection

The information presented here illuminates the intricate biological dialogue between your hormonal systems and your cognitive health. Understanding that your brain’s response to a therapy is deeply tied to your life stage is a powerful first step. This knowledge transforms abstract symptoms into a coherent biological narrative, shifting the focus from passive experience to active understanding.

Your personal health journey is unique, defined by your specific biology, history, and goals. The path forward involves using this foundational knowledge to engage in informed, collaborative discussions with your clinical team, ensuring your protocol is aligned not just with a diagnosis, but with your individual potential for vitality and function.