Fundamentals

Your body communicates its status through a precise language of biological markers. The numbers from a biometric screening ∞ your glucose levels, your lipid panel, your blood pressure ∞ are direct readouts from your endocrine and metabolic systems. They represent the intricate hormonal conversations that dictate your energy, your mood, and your overall vitality.

When an employer wellness program offers an incentive in exchange for this information, you are being asked to share a uniquely personal dataset. The alignment of these programs with privacy protections begins with a foundational question of structure.

The applicability of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) is determined by how the wellness program is administered. A program offered as a component of your group health plan operates under the full protection of HIPAA rules. In this arrangement, your personal health information is shielded by rigorous privacy and security standards.

The information flows within the healthcare system, subject to the same safeguards that protect your conversations with a physician or the results of a hospital lab test.

The architecture of a wellness program dictates the level of privacy afforded to your biological data.

Conversely, a wellness program offered directly by your employer, separate from the group health plan, exists outside of HIPAA’s jurisdiction. Health information collected in this context may not receive the same level of protection. While other regulations, such as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), impose confidentiality requirements, the specific framework of HIPAA does not apply.

Understanding this structural distinction is the first step in comprehending the landscape of your health data privacy and its connection to your personal biological journey.

What Is Protected Health Information?

Protected Health Information (PHI) includes any identifiable health data collected or held by a covered entity. This encompasses a wide spectrum of personal details, from your name and birth date to your medical diagnoses, lab results, and biometric measurements.

The information gathered during a wellness screening, such as cholesterol levels or body mass index, constitutes PHI when the program is part of a group health plan. This classification is what activates HIPAA’s protective measures, restricting how the data can be used and disclosed. The core principle is that this information belongs to you, and its use by others is strictly regulated to serve your health interests.

Intermediate

The regulatory framework governing wellness incentives operates on a key distinction between two types of program designs. This classification determines the level of scrutiny applied to ensure fairness and protect participants from discriminatory practices. Understanding this division illuminates how incentives are structured to encourage participation while adhering to federal privacy and nondiscrimination laws. The two primary models are participatory programs and health-contingent programs, each with its own set of rules and implications for your health journey.

Participatory wellness programs are the most straightforward. They reward participation without requiring an individual to meet a specific health standard. An incentive might be offered for simply completing a Health Risk Assessment (HRA) or attending a nutrition seminar. Because they do not tie rewards to health outcomes, these programs generally have fewer regulations under HIPAA. The primary requirement is that they are made available to all similarly situated individuals.

Health-contingent wellness programs link incentives to the achievement of specific biometric targets.

Health-contingent programs introduce a greater degree of complexity. These programs require individuals to satisfy a standard related to a health factor to obtain a reward. They are further divided into two subcategories ∞ activity-only programs and outcome-based programs.

Activity-only programs require performing a health-promoting activity, such as walking or dieting, without requiring a specific health outcome. Outcome-based programs, which involve the most stringent rules, require attaining a specific health outcome, like achieving a target cholesterol level or blood pressure reading.

Key Requirements for Health Contingent Programs

To maintain compliance, outcome-based wellness programs must satisfy five specific criteria. These rules are designed to ensure the programs are fair, reasonable, and do not become a method for penalizing individuals for health factors outside their control. They represent a clinical and ethical scaffolding around the use of incentives.

- Frequency of Qualification. Individuals must be given the opportunity to qualify for the reward at least once per year.

- Size of Reward. The total incentive is limited. Generally, the reward cannot exceed 30% of the total cost of employee-only health coverage. This cap can increase to 50% for programs designed to prevent or reduce tobacco use.

- Reasonable Design. The program must be reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease. It cannot be overly burdensome or based on methods that are scientifically unsound.

- Uniform Availability and Reasonable Alternatives. The full reward must be available to all similarly situated individuals. For those whom it is medically inadvisable or unreasonably difficult to meet the standard, a reasonable alternative standard must be provided.

- Notice of Alternative. All program materials must disclose the availability of a reasonable alternative standard to qualify for the reward.

How Do Incentives Affect Program Design?

Incentives serve as a behavioral catalyst, yet their implementation requires careful calibration to align with both HIPAA and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). The size of the incentive is a central point of regulatory focus. A substantial financial reward may influence an individual’s decision to share sensitive health data, raising questions about the voluntariness of participation.

The legal limits on incentives are intended to strike a balance, encouraging engagement without becoming coercive. This ensures that participation remains a choice, preserving the autonomy of the individual in their health management.

| Program Type | Description | Incentive Structure | Key HIPAA Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participatory | Rewards participation without regard to health outcomes. | Based on completion (e.g. filling out a questionnaire). | Must be available to all similarly situated individuals. |

| Health-Contingent (Activity-Only) | Requires undertaking an activity (e.g. a walking program). | Based on participation in the activity. | Requires reasonable alternative standards. |

| Health-Contingent (Outcome-Based) | Requires meeting a specific health target (e.g. target BMI). | Based on achieving the health outcome. | Subject to five strict requirements, including incentive limits. |

Academic

The intersection of wellness incentives, HIPAA, and other federal statutes like the ADA and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) creates a complex regulatory environment where the definition of “voluntary” is intensely debated.

While HIPAA provides a pathway for wellness programs to operate as an exception to its nondiscrimination rules, the ADA requires that any medical examinations or inquiries conducted by an employer be part of a voluntary employee health program. The tension arises from the size of the incentive offered; a large financial reward can be perceived as coercive, thus rendering the program non-voluntary under the ADA’s interpretation.

This conflict has been the subject of legal challenges and shifting regulatory guidance. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), which enforces the ADA and GINA, has historically expressed concern that large incentives could pressure employees into divulging sensitive health and genetic information. Court cases, such as AARP v.

EEOC, have scrutinized the regulations, leading to the vacation of rules that had previously allowed for higher incentive limits. This legal friction highlights a fundamental divergence in philosophy between promoting public health outcomes through financial motivation and protecting individual autonomy and privacy.

The Neuroendocrine Impact of Financial Pressure

The debate over incentive size has profound implications from a physiological perspective. A significant financial incentive, such as a premium differential amounting to thousands of dollars, can act as a potent external stressor.

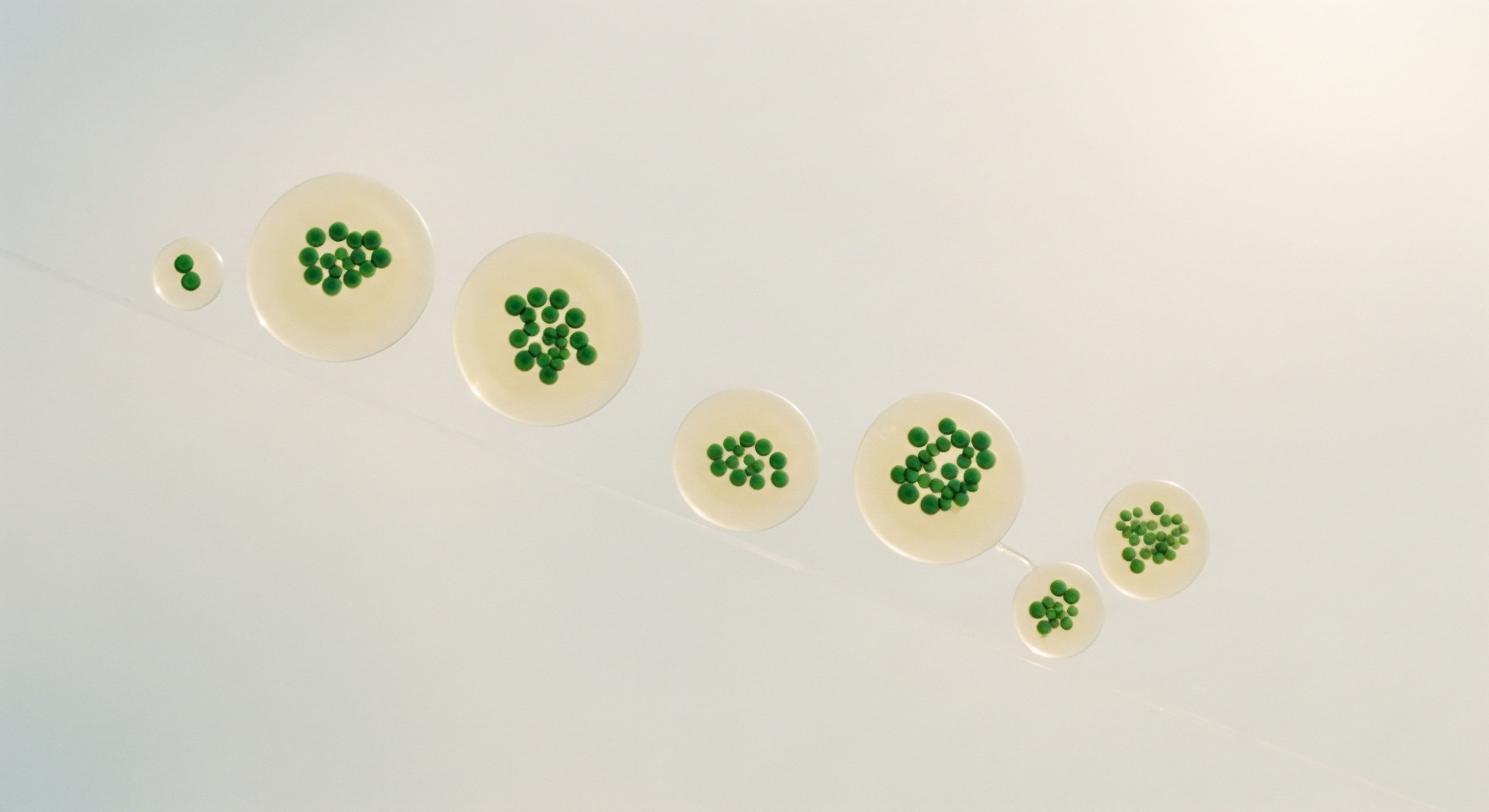

For an individual struggling to meet a biometric target ∞ perhaps due to genetic predispositions, socioeconomic factors, or underlying endocrine dysregulation ∞ the prospect of a financial penalty can induce a state of chronic stress. This stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the body’s central stress response system.

Sustained HPA axis activation leads to elevated levels of cortisol, a primary stress hormone. Chronically high cortisol can disrupt metabolic function, leading to insulin resistance, increased abdominal fat storage, and suppressed immune function. It can also dysregulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, affecting reproductive hormones.

In this context, a wellness program designed to improve metabolic health could paradoxically degrade it through the neuroendocrine consequences of the financial pressure it imposes. The very mechanism intended to promote wellness becomes a source of physiological burden, illustrating a deep disconnect between program design and human biology.

The pressure to meet wellness targets can trigger a physiological stress response that undermines metabolic health.

Data Flow and Privacy in Integrated Wellness Programs

When a wellness program is integrated with a group health plan, the flow of PHI is governed by specific HIPAA protocols. The wellness vendor, acting as a business associate of the health plan, can analyze individual data to administer the program. However, the information that flows back to the employer (the plan sponsor) is strictly limited.

The employer should only receive aggregated, de-identified data for assessing program effectiveness or summary information about participation. This structure is designed to create a firewall, preventing the employer from using an individual’s specific health status for employment-related decisions.

| Data Originator | Data Transmitted | Recipient | Governing Rule |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employee | Biometric Data, HRA Responses | Wellness Vendor (Business Associate) | HIPAA Privacy & Security Rules |

| Wellness Vendor | Individual Progress, Need for Alternative | Group Health Plan (Covered Entity) | Business Associate Agreement |

| Group Health Plan | Aggregated, De-identified Data | Employer (Plan Sponsor) | HIPAA Privacy Rule §164.504(f) |

| Group Health Plan | Participation Information (Yes/No) | Employer (Plan Sponsor) | HIPAA Privacy Rule §164.504(f) |

This regulated data flow is the cornerstone of HIPAA’s alignment with wellness incentives. It permits the operation of health-contingent programs while attempting to mitigate the risk of discrimination. The integrity of this system relies on the strict adherence of all parties ∞ the covered entity, its business associates, and the plan sponsor ∞ to the established privacy and security protocols. Any breach in this chain of custody compromises the foundational trust necessary for such programs to function ethically.

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “HIPAA Privacy and Security and Workplace Wellness Programs.” HHS.gov, 20 April 2015.

- U.S. Department of Labor. “Fact Sheet ∞ The Affordable Care Act and Wellness Programs.” DOL.gov, 2013.

- Livingston, Catherine, and Rick Bergstrom. “Wellness Programs ∞ Navigating the Legal Morass.” Employee Relations Law Journal, vol. 40, no. 2, 2014, pp. 63-79.

- Schilling, Brian. “What do HIPAA, ADA, and GINA Say About Wellness Programs and Incentives?” American Journal of Health Promotion, vol. 26, no. 4, 2012, pp. 1-4.

- Madison, Kristin M. “The Law and Policy of Workplace Wellness.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science, vol. 12, 2016, pp. 99-115.

- Haffey, T. L. “AARP v. EEOC ∞ The Logjam Breaking for Employer Wellness Programs.” Benefits Law Journal, vol. 31, no. 1, 2018, pp. 53-61.

- Sapolsky, Robert M. Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers ∞ The Acclaimed Guide to Stress, Stress-Related Diseases, and Coping. Holt Paperbacks, 2004.

- McEwen, Bruce S. “Stress, Adaptation, and Disease ∞ Allostasis and Allostatic Load.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 840, no. 1, 1998, pp. 33-44.

Reflection

The knowledge of how your biological data is handled within wellness frameworks provides a new lens through which to view your health journey. This understanding moves you from a passive participant to an informed steward of your own physiology. Consider the language your body is speaking through its unique metabolic and endocrine signatures.

What does it mean to translate that language into data points, and who becomes the custodian of that translation? Your personal health narrative is written in the daily function of your cells and systems. The path to reclaiming vitality is paved with a deep, personal comprehension of this internal biology, allowing you to make choices that are authentically aligned with your body’s needs, independent of any external program or incentive.