Fundamentals

Navigating the landscape of employer-sponsored wellness programs can feel like trying to read a complex diagnostic chart without a clinical background. You are presented with opportunities to engage with your health in a new way, often with financial incentives attached, yet this invitation can be accompanied by a sense of vulnerability.

Sharing personal health information, the very data that tells the story of your body’s internal workings, is a significant act of trust. It is within this deeply personal space that two distinct regulatory frameworks, one overseen by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and the other shaped by the Affordable Care Act (ACA), establish the rules of engagement. Understanding their differing philosophies is the first step in comprehending the architecture of these programs and your place within them.

The journey into your own health data, whether it is the level of morning cortisol that dictates your energy or the thyroid hormones that govern your metabolism, is profoundly personal. The numbers on a lab report are more than data points; they are the language of your lived experience.

They explain the fatigue that lingers, the subtle shifts in mood, or the unexpected changes in your body’s composition. The EEOC’s role, rooted in civil rights law, is to protect this personal narrative. Its authority stems from the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA).

These laws are designed to build a fortress of confidentiality around your health status, ensuring that your biological uniqueness does not become a basis for discrimination in the workplace. The EEOC’s primary concern is ensuring that your participation in any wellness program is genuinely voluntary, a choice made freely without undue pressure or penalty.

The Philosophy of Protection

The ADA and GINA function as guardians of your biological privacy. The ADA protects individuals with disabilities, a category that can include a wide array of physiological conditions, from metabolic syndrome to autoimmune disorders. GINA extends this protection to your genetic blueprint, recognizing that your family health history contains predictive information that is uniquely sensitive.

From the EEOC’s perspective, a wellness program that requires medical examinations or asks questions about health history must pass a high bar for voluntariness. The commission scrutinizes the structure of incentives, asking a critical question ∞ at what point does a reward for participation become a penalty for non-participation?

This is a crucial distinction. A program that feels coercive can create a subtle but pervasive stress, activating the body’s sympathetic nervous system and potentially disrupting the very hormonal balance it purports to improve. The EEOC’s framework is built upon the principle that your health data belongs to you, and any request to share it must be free from compulsion.

The Perspective of Public Health

The Affordable Care Act approaches wellness programs from a different, albeit complementary, vantage point. The ACA’s regulations, which amend the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), are situated within a public health context. The goal is to encourage behaviors that can lead to better health outcomes across a population, which in turn can help manage the rising costs of healthcare.

The ACA permits employers to offer significant financial incentives tied to wellness programs. It creates specific pathways for both “participatory” programs, which reward employees simply for taking part, and “health-contingent” programs, which require individuals to meet a specific health outcome, such as achieving a certain cholesterol level or blood pressure reading.

The ACA’s rules provide a structured framework for these incentives, viewing them as a tool to motivate positive health changes. This perspective is built on the idea that well-designed programs can serve as a catalyst for individuals to engage more proactively with their health, leading to early detection of potential issues and better management of chronic conditions.

The EEOC champions the sanctity of voluntary participation to prevent discrimination, while the ACA provides a structured framework for using incentives to promote population-wide health engagement.

What Defines a Truly Voluntary Program?

The core of the divergence between these two regulatory bodies lies in the definition of “voluntary.” For the EEOC, the term is anchored in the principles of civil rights. A program is voluntary if an employee’s decision to participate or not has no meaningful financial or professional consequence.

The commission is wary of programs where the incentive is so large that it feels like a mandatory part of an employee’s compensation package, effectively penalizing those who choose to keep their health information private. This is particularly salient for individuals managing chronic conditions, who may not be able to meet certain health targets or who may simply wish to keep their health journey separate from their employment.

The ACA, on the other hand, defines “voluntary” in more procedural terms. It establishes clear limits on the value of incentives, creating a ceiling that it deems acceptable. As long as a program adheres to these financial limits and provides reasonable alternatives for individuals who cannot meet the required health outcomes, it is considered to be in compliance.

This approach gives employers a clear, quantifiable set of rules to follow when designing their wellness initiatives. The tension between these two philosophies creates a complex operational reality for employers and a nuanced experiential reality for employees. It is a dialogue between the protection of the individual and the promotion of collective health, a conversation that shapes the very nature of wellness in the workplace.

Intermediate

To move from the philosophical underpinnings to the practical application of EEOC and ACA regulations is to enter the engine room of wellness program design. Here, the abstract principles of voluntariness and non-discrimination are translated into specific, quantifiable rules that govern the structure of incentives.

The primary distinction crystallizes around two types of wellness programs ∞ participatory and health-contingent. Understanding this division is the key to decoding the intricate regulatory landscape. A participatory program is one where the reward is earned simply for engaging in an activity, such as completing a health risk assessment (HRA) or attending a seminar, regardless of the results.

A health-contingent program, conversely, requires an individual to meet a specific health standard to earn an incentive. This could involve achieving a target body mass index (BMI), lowering blood pressure, or quitting tobacco.

The ACA provides a detailed blueprint for both types of programs, with a particular focus on health-contingent models. It allows for substantial financial incentives, viewing them as a powerful lever to drive health improvements.

The EEOC’s rules, flowing from the ADA and GINA, cast a watchful eye over any program that involves a medical inquiry or examination, which includes most health-contingent programs and many participatory ones. The commission’s central concern is whether the program is “reasonably designed” to promote health and not merely a tool for shifting costs or gathering data. This “reasonably designed” standard requires a holistic assessment of the program’s intent and function, moving beyond simple compliance with numerical limits.

Dissecting the Incentive Limits

The most concrete point of divergence between the two frameworks is the calculation of maximum incentive values. While both often refer to a 30% threshold, the devil is in the details of what that 30% is based on. This difference has significant financial and structural implications for how a program is built and offered to employees and their families.

The ACA allows the 30% incentive to be based on the total cost of the health plan coverage in which an employee is enrolled. If an employee has family coverage, the incentive can be calculated based on that higher premium. This allows for a larger dollar-value incentive, which employers might see as a more effective motivator.

Furthermore, for programs designed to reduce tobacco use, the ACA raises this limit to 50%, a clear signal of the public health priority placed on smoking cessation.

The EEOC’s proposed guidance, however, took a more restrictive stance. It stipulated that the 30% limit should be calculated based on the cost of self-only coverage, regardless of whether the employee is enrolled in a more expensive family plan. This significantly curtails the potential size of the incentive.

The EEOC’s reasoning is that a large, family-plan-based incentive could be coercive, compelling an employee to participate simply to avoid a substantial financial penalty on their family’s health coverage. The commission also did not adopt the ACA’s higher 50% limit for tobacco cessation programs if those programs required biometric screening or other medical exams to verify tobacco use.

This is because the act of medical testing brings the program squarely under the purview of the ADA’s rules on voluntary medical examinations.

A Comparative Analysis of Incentive Structures

To illustrate the practical differences, a table can clarify the operational distinctions in how these incentives are calculated. This comparison reveals the fundamental tension between the ACA’s goal of broad-based health motivation and the EEOC’s focus on individual protection.

| Regulatory Framework | Basis for Incentive Calculation | Maximum Incentive (General) | Maximum Incentive (Tobacco Cessation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affordable Care Act (ACA) | Total cost of the specific coverage tier the employee is enrolled in (e.g. self-only, family). | 30% of the total cost of coverage. | Up to 50% of the total cost of coverage. |

| Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) | Total cost of self-only coverage, regardless of the employee’s actual enrollment. | 30% of the total cost of self-only coverage. | 30% of the total cost of self-only coverage if a medical exam (e.g. nicotine test) is required. |

What Are the Rules for Spouses and Dependents?

The regulations governing the participation of spouses and dependents in wellness programs add another layer of complexity. GINA specifically prohibits employers from requesting genetic information, which includes the manifestation of diseases or disorders in family members. This has direct implications for health risk assessments that inquire about family medical history.

The EEOC’s final rule on GINA created a specific, limited exception allowing employers to offer an incentive to a spouse to provide information about their own health status as part of a wellness program. However, the incentive limit for the spouse is tied to the same 30% of self-only coverage rule.

GINA maintains a strict prohibition on offering incentives for information about the health of an employee’s children or for the spouse’s genetic information. The ACA’s framework is generally more permissive, allowing for family participation in wellness programs as long as the overall incentive structure adheres to its percentage limits based on the family coverage premium.

The calculation of incentive limits, particularly the choice between self-only and family coverage as the cost basis, represents a critical operational divergence between EEOC and ACA guidelines.

This intricate web of rules requires employers to navigate carefully. A program that is perfectly compliant with the ACA’s incentive structure could potentially be viewed as coercive under the EEOC’s interpretation, especially if the incentives are high and tied to family coverage.

The legal challenges that led to the vacating of the EEOC’s 2016 rules have created a state of regulatory ambiguity, leaving employers in a difficult position. They must balance the desire to create effective, motivating wellness programs with the need to mitigate the legal risks associated with potential ADA and GINA violations. For the employee, this regulatory tension underscores the importance of understanding the specific design of their employer’s program and their rights under each of these foundational laws.

- Participatory Programs ∞ These generally face less scrutiny, but if they include a health risk assessment or biometric screening, they still fall under the ADA’s purview and must be voluntary and reasonably designed.

- Health-Contingent Programs ∞ These are the primary focus of both ACA and EEOC regulations. They must satisfy the incentive limits and provide reasonable alternatives for individuals who cannot meet the health outcomes due to a medical condition.

- Reasonable Alternatives ∞ Both frameworks mandate that individuals who cannot meet a health target due to a medical condition must be offered a reasonable alternative way to earn the incentive. For example, if an employee has a medical condition that prevents them from meeting a cholesterol target, the plan might allow them to earn the reward by following their doctor’s recommendations for managing the condition.

Academic

The dialectic between the EEOC’s civil rights-based framework and the ACA’s public health-oriented approach to wellness program regulation is more than a matter of conflicting percentage points. It represents a profound epistemological tension in how we define health, autonomy, and responsibility within the context of the modern employer-employee relationship.

This tension was brought into sharp relief by the legal proceedings in AARP v. EEOC, which resulted in a federal court vacating the incentive limit portions of the EEOC’s 2016 ADA and GINA rules.

The court’s decision did not invalidate the underlying principle that wellness programs must be voluntary; rather, it found that the EEOC had failed to provide a reasoned explanation for how it arrived at its 30% incentive limit, leaving a regulatory vacuum that persists to this day. This legal uncertainty forces a deeper, more critical examination of the assumptions embedded within each regulatory scheme.

The ACA’s regulations operate within a biopolitical framework, viewing the employee population as a body to be managed for optimal health and reduced cost. The use of financial incentives is a form of soft power, a nudge intended to steer individuals toward healthier behaviors.

This model presupposes a rational actor who will respond to economic stimuli in a predictable way. From a systems biology perspective, this is a profoundly linear and mechanistic view of human health. It risks reducing complex, multifactorial conditions like obesity, diabetes, or dyslipidemia to simple matters of individual choice and compliance, overlooking the intricate interplay of genetics, epigenetics, socioeconomic factors, and the pervasive influence of the endocrine and nervous systems.

The Neuroendocrine Impact of Financial Coercion

The EEOC’s concern with coercion can be interpreted through a neuroendocrine lens. A wellness program with an incentive so high that it becomes a de facto penalty for non-compliance can act as a chronic psychosocial stressor. This stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, leading to elevated and dysregulated cortisol secretion.

Chronic cortisol elevation is implicated in a cascade of deleterious metabolic effects ∞ it promotes visceral adiposity, induces insulin resistance, suppresses thyroid function, and can have catabolic effects on muscle and bone tissue. In a bitter irony, a wellness program designed to improve metabolic health could, through the mechanism of financial stress, actually exacerbate the very conditions it aims to prevent.

An individual with a genetic predisposition to insulin resistance, for example, may find it difficult to meet a target for fasting glucose. The daily stress of facing a significant financial penalty for this “failure” could further drive their insulin resistance through HPA axis activation, creating a vicious physiological cycle. The EEOC’s focus on a truly voluntary standard, therefore, can be seen as an implicit recognition of the biological consequences of coercion.

Table of Conflicting Legal and Biological Philosophies

The table below synthesizes the divergent philosophies, moving beyond mere regulatory differences to explore the underlying assumptions about human biology and behavior. This academic deconstruction highlights the core of the conflict.

| Concept | Affordable Care Act (ACA) Perspective | Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) Perspective |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Population health management and cost containment through behavioral modification. | Protection of individual civil rights and prevention of discrimination based on health status. |

| View of the Employee | A rational actor who can be incentivized toward optimal health behaviors. | An autonomous individual with a right to privacy and protection from coercion. |

| Implied Biological Model | Mechanistic and behavioral; assumes health outcomes are primarily a function of individual lifestyle choices. | Systemic and psychobiological; acknowledges that stress and coercion have physiological consequences that can undermine health. |

| Definition of “Voluntary” | Procedural; a program is voluntary if it adheres to specified financial incentive limits and offers reasonable alternatives. | Substantive; a program is voluntary only if the employee’s choice is free from significant financial or other pressure. |

How Do These Frameworks Address Complex Health Protocols?

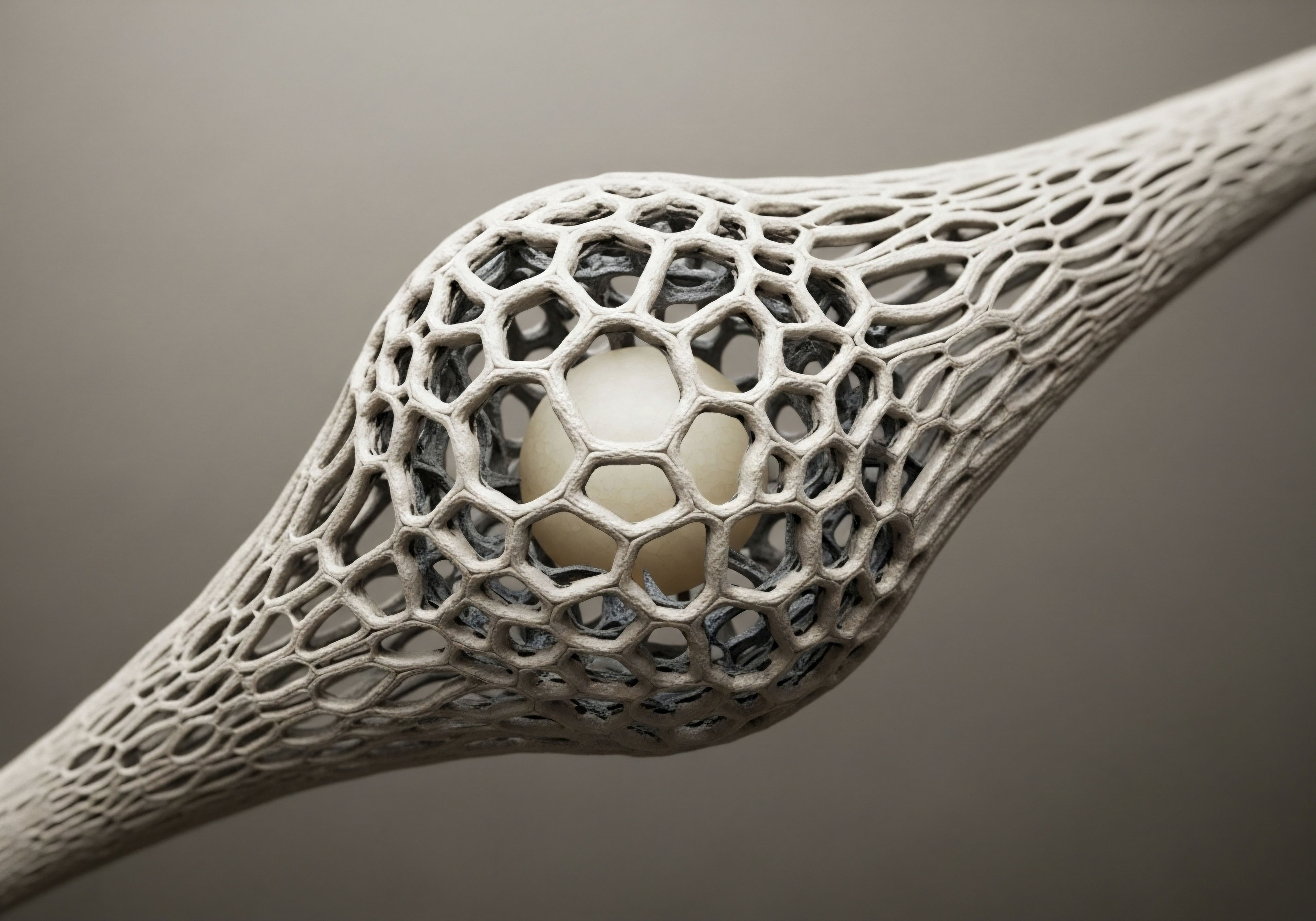

The existing regulatory frameworks, designed around simple metrics like BMI and blood pressure, are ill-equipped to handle the future of personalized and preventative medicine. Consider the clinical protocols that represent the cutting edge of proactive wellness, such as hormone optimization therapies or advanced peptide treatments.

A wellness program that sought to screen for and support men with symptomatic hypogonadism would run into immediate regulatory friction. The necessary biometric screening (total and free testosterone, estradiol, LH, FSH) is a clear medical examination under the ADA. The “outcome” is the restoration of hormonal balance, a complex clinical process guided by a physician, not a simple target to be met.

How would an incentive be structured for such a program? Would it be rewarded for starting Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT)? For achieving a certain testosterone level? Each of these possibilities raises profound ethical and legal questions.

The EEOC’s framework would demand extreme care to ensure that no employee felt pressured to disclose a diagnosis of low testosterone or to embark on a course of treatment. The ACA’s model, with its focus on quantifiable outcomes, struggles to accommodate the personalized, long-term nature of such protocols.

This reveals the limitations of a regulatory paradigm built for a 20th-century understanding of wellness. As our understanding of health becomes more sophisticated, moving toward a systems-based, personalized model, the legal and regulatory frameworks that govern workplace wellness will need to evolve with it. They must move beyond a simple dichotomy of incentive versus penalty and toward a more nuanced understanding of how to support an individual’s unique and complex journey toward reclaiming their own biological vitality.

The legal ambiguity created by the AARP v. EEOC decision highlights a deeper need for a regulatory evolution that can accommodate a systems-biology understanding of health.

The current state of affairs leaves employers navigating a treacherous legal landscape with an outdated map. The path forward requires a new synthesis, one that integrates the ACA’s ambition for better population health with the EEOC’s non-negotiable commitment to individual rights and autonomy.

This future framework must be flexible enough to accommodate the complexities of modern clinical science while remaining grounded in the fundamental principle that true wellness cannot be coerced; it must be a voluntary and empowered choice. It necessitates a move from a paradigm of control to one of support, recognizing that the most powerful wellness tool an employer can offer is a work environment that reduces chronic stress and respects the biological and psychological integrity of every employee.

- The Principle of Non-Coercion ∞ This remains the bedrock legal standard. The central question for any program designer is whether a reasonable person would feel compelled to participate due to the size of the incentive.

- The “Reasonably Designed” Standard ∞ A program must be more than a data-gathering exercise. It must have a clear and demonstrable purpose related to promoting health or preventing disease. It should provide feedback, support, and follow-up resources to participants.

- The Problem of Genetic Information ∞ GINA’s strict rules on requesting family medical history remain a critical compliance checkpoint. Health risk assessments must be carefully designed to avoid soliciting this information, even indirectly.

References

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. “Questions and Answers about the EEOC’s Final Rule on Employer Wellness Programs and the Americans with Disabilities Act.” 2016.

- “Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.” Public Law 111-148, 124 Stat. 119. 2010.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Department of Labor, U.S. Department of the Treasury. “Final Rules Under the Affordable Care Act for Improvements to Private Health Insurance.” Federal Register, vol. 78, no. 106, 2013, pp. 33158-33201.

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. “Final Rule on Employer Wellness Programs and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act.” Federal Register, vol. 81, no. 95, 2016, pp. 31143-31156.

- AARP v. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 267 F. Supp. 3d 14 (D.D.C. 2017).

- “Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.” Public Law 101-336, 104 Stat. 327. 1990.

- “Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008.” Public Law 110-233, 122 Stat. 881. 2008.

- “Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996.” Public Law 104-191, 110 Stat. 1936. 1996.

- Schilling, Brian. “What do HIPAA, ADA, and GINA Say About Wellness Programs and Incentives?” Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2012.

- Pollitz, Karen, and Ashley Semanskee. “Workplace Wellness Programs Characteristics and Requirements.” KFF, 2016.

Reflection

You have now traveled through the intricate architecture of wellness program regulation, from the foundational philosophies to the complex legal realities. This knowledge serves a purpose beyond academic understanding. It is a tool for self-advocacy and informed choice. Your health narrative is uniquely your own, a complex and dynamic interplay of biology, environment, and personal history.

The data points on a screening report are merely chapter markers in this story. As you encounter wellness initiatives in your own life, you are now equipped to look beyond the surface-level offer of an incentive. You can begin to ask deeper questions.

Does this program feel like a supportive resource or a source of pressure? Is it designed with a nuanced understanding of health, or does it promote a one-size-fits-all approach? Does it respect your right to privacy and autonomy?

The answers to these questions will help you determine how, and on what terms, you choose to engage. This journey of understanding the systems that surround you is the first, most powerful step in taking ownership of the systems within you, charting a course toward vitality that is defined by your own goals and your own wisdom.

Glossary

financial incentives

wellness programs

equal employment opportunity commission

affordable care act

genetic information nondiscrimination act

americans with disabilities act

wellness program

ada and gina

health outcomes

public health

reasonable alternatives

health-contingent programs

reasonably designed

family coverage

self-only coverage

biometric screening

genetic information

incentive limit

eeoc regulations

incentive limits

aarp v. eeoc