Fundamentals

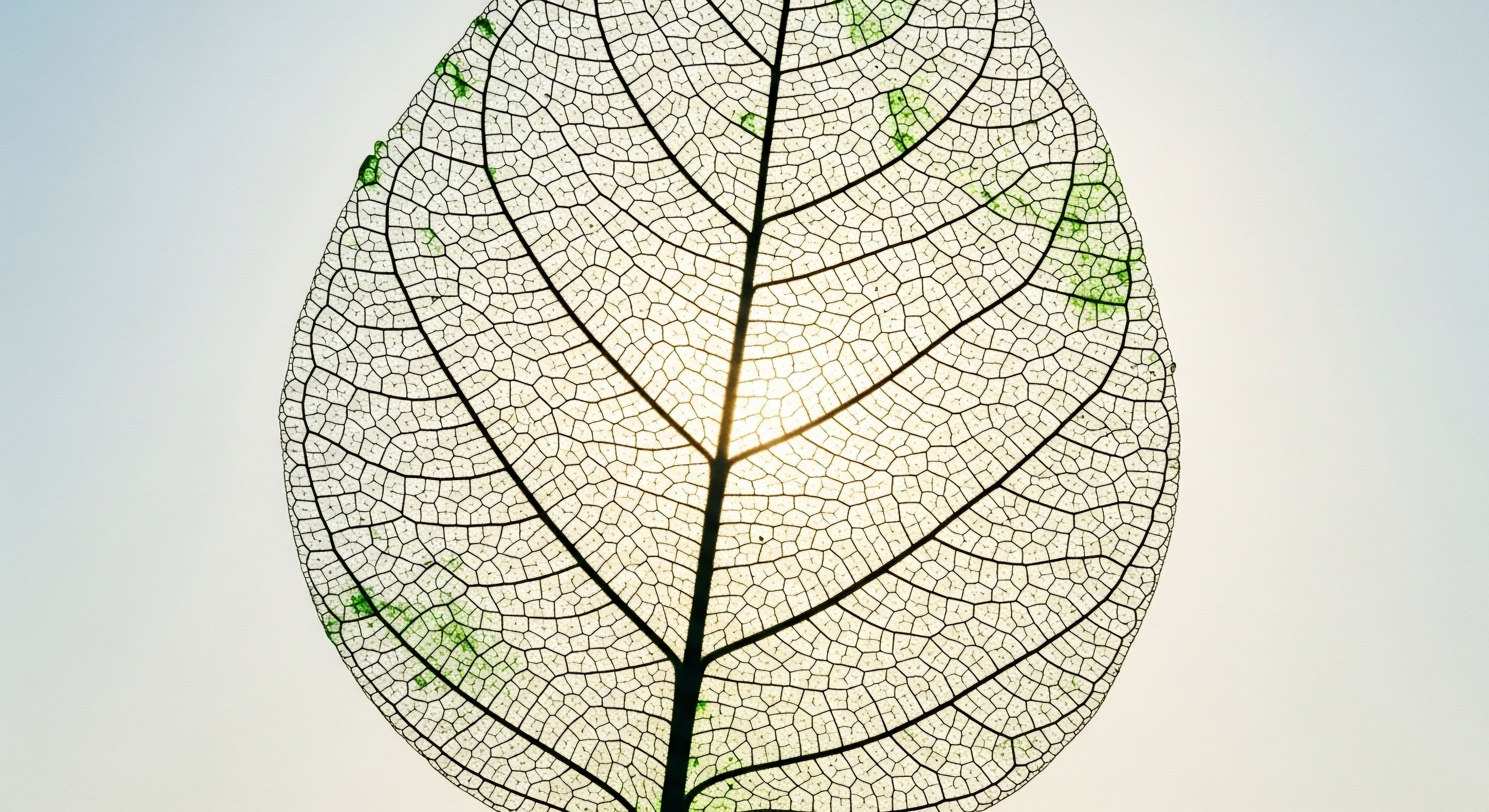

Your body is a complex, interconnected system. Every signal, from the subtle shift in energy you feel after a meal to the profound changes that mark life’s stages, is part of a conversation conducted by your endocrine and metabolic systems. Understanding this internal dialogue is the first step toward optimizing your health.

This journey often involves gathering data ∞ lab results, biometric screenings, and even knowledge of your family’s health patterns. As you seek to understand your unique biology, you will encounter the world of workplace wellness programs, which often encourage this kind of data collection.

It is here, at the intersection of personal health discovery and employment, that two critical legal frameworks come into play The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA). These laws establish the boundaries for how much an employer can ask about your health and what they can offer in return. They are the guardians of your private biological information within the professional sphere.

The path to personalized wellness requires a deep understanding of your own biological systems. This understanding is built upon data, some of which is the most personal information you possess. When an employer offers a wellness program, it creates a dynamic where you are asked to share pieces of this personal health puzzle.

The core purpose of the ADA and GINA in this context is to ensure that your participation in such programs is truly voluntary. These laws are designed to protect your autonomy, ensuring that the incentives offered do not become so substantial that they feel coercive, compelling you to disclose sensitive health information you would otherwise keep private. They function as a regulatory buffer, preserving the integrity of your personal health journey against workplace pressures.

The Foundational Role of the ADA

The Americans with Disabilities Act is a landmark civil rights law. Its primary objective is to prevent discrimination against individuals with disabilities in all areas of public life, including employment. Within the workplace, the ADA restricts an employer’s ability to make medical inquiries or require medical examinations of its employees.

This is a crucial protection. It prevents an employer from making employment decisions based on your health status, a pre-existing condition, or a perceived disability. The law recognizes that your health information is confidential and should not be a factor in your career advancement, job security, or the terms of your employment.

However, the ADA includes an important exception for voluntary employee health programs. An employer is permitted to conduct medical examinations, such as biometric screenings or health risk assessments, if they are part of a voluntary wellness program. The term “voluntary” is the central pivot upon which the entire regulatory framework turns.

For decades, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the agency that enforces the ADA, has worked to define what makes a program voluntary. A key aspect of this definition relates to incentives. If an incentive is too large, it could be seen as punitive for those who choose not to participate, effectively making the program mandatory and violating the ADA.

This is where the rules become complex, as different governmental bodies have, at times, held conflicting views on what constitutes an acceptable incentive level.

Understanding GINA’s Unique Protections

The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act provides a more recent and highly specific layer of protection. GINA was enacted to address the growing field of genetic science and the potential for misuse of this deeply personal information. The law prohibits health insurers and employers from discriminating against individuals based on their genetic information.

This information is defined broadly. It includes the results of your genetic tests, the genetic tests of your family members, and your family medical history. GINA recognizes that your genetic makeup, which can reveal predispositions to future health conditions, is a private matter that should not be used to your disadvantage in securing health insurance or employment.

In the context of wellness programs, GINA places strict limits on an employer’s ability to request, require, or purchase genetic information. This most commonly arises when a health risk assessment includes questions about your family’s medical history. For example, asking if a parent had heart disease or if a sibling has a specific genetic condition falls under GINA’s purview.

The law is designed to prevent a situation where an employer could gather data on its workforce’s genetic predispositions. Like the ADA, GINA allows for the collection of this information only under specific, voluntary circumstances. The rules around incentives under GINA are even more stringent, reflecting the sensitive and predictive nature of genetic data. The law aims to ensure that you are never financially pressured into revealing your family’s health blueprint.

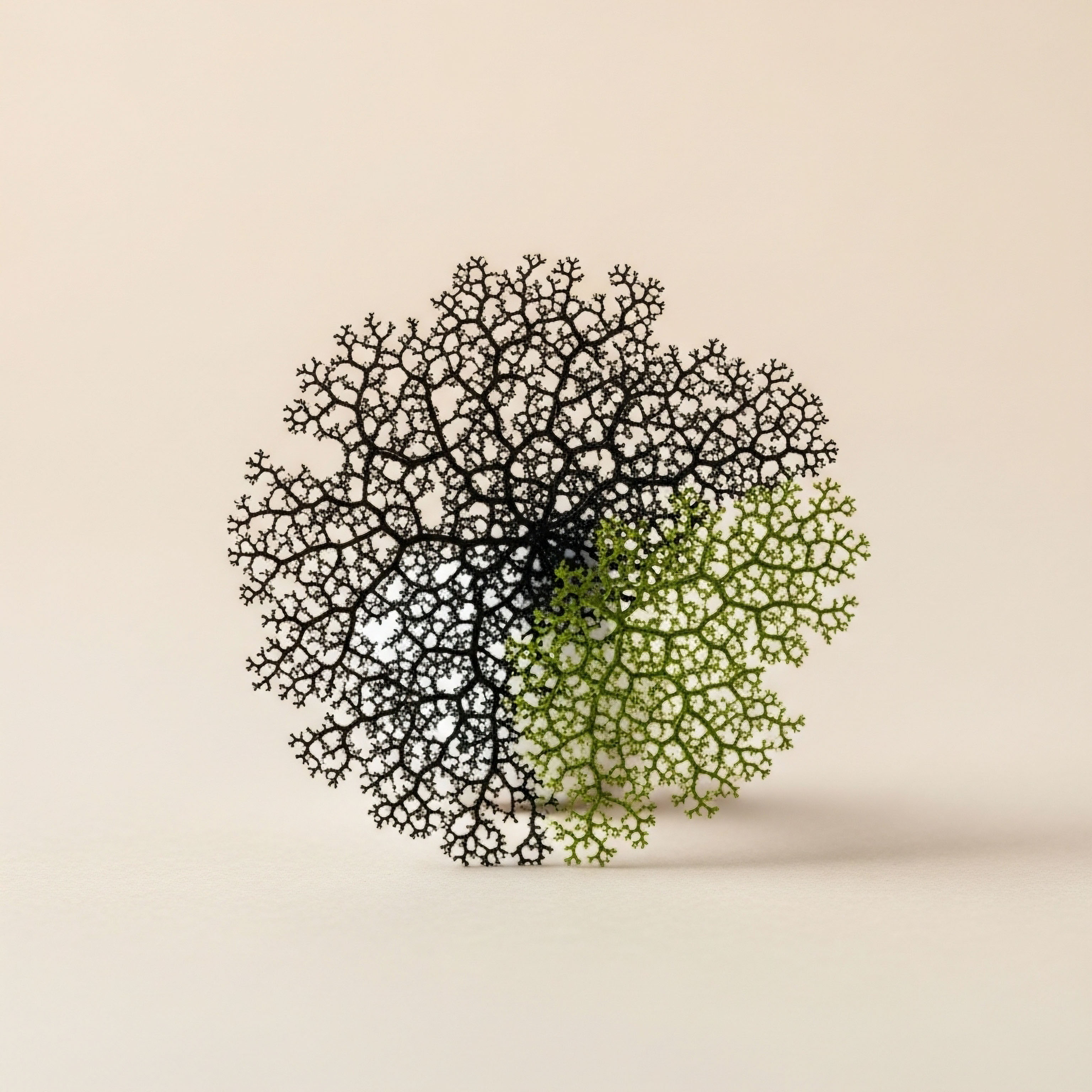

The ADA and GINA act as legal shields, protecting the privacy of an individual’s personal health and genetic data within the context of employer-sponsored wellness initiatives.

The interaction between these two laws creates a complex regulatory landscape for employers seeking to implement wellness programs. While the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) also has rules for wellness programs, the EEOC’s interpretation of the ADA and GINA focuses specifically on the “voluntary” nature of programs that include medical inquiries or requests for genetic information.

The core difference in their application to wellness incentives stems from the type of information being requested. The ADA is triggered when a program asks disability-related questions or requires a medical exam. GINA is triggered when a program asks for genetic information, including family medical history. This distinction is the foundation for understanding why the incentive rules differ and how they work together to protect your private health information.

Intermediate

Navigating the specifics of the ADA and GINA rules on wellness incentives requires a more detailed examination of how these laws are applied in practice. The central tension lies in balancing an employer’s desire to encourage healthy behaviors through financial incentives with the legal mandate that participation in health-related inquiries must be voluntary.

The rules set forth by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) have evolved over time, reflecting a continuous dialogue between regulators, employers, and advocacy groups about where to draw the line between a permissible incentive and a coercive one. This has led to a fluctuating landscape of regulations, with periods of clear guidance followed by legal challenges and revisions.

The key distinction to grasp is that the ADA and GINA apply to different components of a wellness program. A single program might trigger one law, both, or neither, depending on its design. For instance, a program that simply offers a reward for attending a nutrition seminar involves no medical inquiry, so the ADA’s incentive limits are not implicated.

However, if that program requires a biometric screening to measure cholesterol levels, it becomes a medical examination, and the ADA’s rules apply. If a Health Risk Assessment (HRA) as part of that same program asks about your parents’ history of cancer, GINA’s protections are triggered. The incentive structure for such a program must therefore comply with both sets of rules simultaneously.

How Do the ADA Incentive Rules Function?

The ADA’s restrictions on incentives are tied to the presence of a disability-related inquiry or a medical examination. When a wellness program includes these elements, the incentive offered to encourage participation cannot be so large as to render the program involuntary.

For years, the debate has centered on a specific percentage of the cost of health insurance. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) allowed for incentives up to 30% of the cost of self-only coverage for health-contingent wellness programs under HIPAA. However, the EEOC, concerned about the voluntary nature required by the ADA, initially proposed a similar 30% limit but faced legal challenges arguing that such a high amount could be coercive for lower-income employees.

This led to a period of uncertainty after a court vacated the 2016 rules, leaving employers without a clear safe harbor. In 2021, the EEOC issued new proposed rules that took a dramatically different direction. These rules suggested that for many wellness programs subject to the ADA, only a “de minimis” incentive could be offered.

This would mean something of trivial value, like a water bottle or a small gift card. The rationale was to remove any significant financial pressure from the employee’s decision to disclose health information. It is important to note that these proposed rules were subsequently withdrawn, leaving the regulatory landscape in flux.

However, the “de minimis” standard illustrates the EEOC’s deep-seated concern that substantial financial rewards can undermine the principle of voluntary participation that is at the heart of the ADA’s exception for employee health programs.

Participatory versus Health-Contingent Programs

A critical distinction within wellness program design is the difference between participatory and health-contingent programs. This distinction has a significant impact on how the rules are applied.

- Participatory Programs ∞ These programs reward an employee simply for participating in an activity, regardless of the outcome. An example would be receiving a gift card for completing a Health Risk Assessment or undergoing a biometric screening. The reward is not tied to achieving any specific health goal.

-

Health-Contingent Programs ∞ These programs require an employee to meet a specific health-related standard to obtain a reward. They are further divided into two subcategories:

- Activity-Only Programs ∞ These require an individual to perform or complete a health-related activity, such as a walking, diet, or exercise program. A reasonable alternative standard must be offered to anyone for whom it is medically inadvisable to participate.

- Outcome-Based Programs ∞ These require an individual to attain or maintain a specific health outcome, such as a certain cholesterol level, blood pressure reading, or BMI. A reasonable alternative standard must also be available for these programs.

Historically, the EEOC’s incentive limits under the ADA were intended to apply to any program that involved a medical inquiry, whether participatory or health-contingent. The now-withdrawn 2021 proposed rules made a clearer distinction, suggesting a de minimis incentive for participatory programs but potentially allowing the larger HIPAA-based incentives for health-contingent programs.

This reflects the ongoing struggle to harmonize the goals of the ACA, which sought to promote outcome-based wellness, with the anti-discrimination principles of the ADA.

The Stricter Limitations of GINA

GINA’s rules on incentives are generally more restrictive than the ADA’s, which is a direct consequence of the nature of the information it protects. Genetic information is predictive, immutable, and reveals information not only about the individual but also about their family members.

For this reason, GINA Title II flatly prohibits employers from offering any financial incentive in exchange for an employee’s own genetic information, including their family medical history. An employer can ask for this information as part of a voluntary wellness program, but they cannot reward an employee for providing it.

The employer must make it clear that the employee will receive the full incentive for completing the Health Risk Assessment, for example, even if they choose to leave the family medical history questions blank.

The fundamental difference in incentive rules lies in the information sought ∞ the ADA governs inquiries into an individual’s current health status, while GINA protects against compelled disclosure of an individual’s genetic blueprint and family medical history.

There is a narrow but important exception under GINA that creates a key point of differentiation from the ADA. GINA allows an employer to offer a limited incentive to an employee in exchange for health information about a spouse who is participating in the wellness program.

The 2016 rules permitted this incentive to be up to the same 30% limit applied under the ADA, calculated based on the cost of self-only coverage. The rationale was that a spouse’s manifested health condition is not the employee’s genetic information. However, this exception does not extend to the employee’s children or other family members.

An employer cannot offer an incentive for an employee to provide health information about their children. The withdrawn 2021 proposed rules sought to limit even the spousal incentive to a de minimis amount, demonstrating the EEOC’s consistent trend toward minimizing financial inducements for any form of genetic or family-related health information.

This creates a complex compliance puzzle. A wellness program that includes a biometric screen for the employee and a health risk assessment for both the employee and their spouse must navigate three separate incentive rules. The incentive for the employee’s screening is governed by the ADA.

The portion of the HRA dealing with the employee’s family medical history is governed by GINA’s general prohibition. The portion of the HRA dealing with the spouse’s own health status is governed by GINA’s spousal exception. An employer must structure their incentive program to respect each of these distinct limitations.

| Feature | Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) | Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) |

|---|---|---|

| Triggering Event | A wellness program that includes a disability-related inquiry or a medical examination (e.g. biometric screening, HRA). | A wellness program that requests, requires, or purchases genetic information (e.g. family medical history). |

| Primary Incentive Limit | The incentive was limited to 30% of the total cost of self-only employee health coverage. (Note ∞ This rule was vacated and future guidance is pending). | No incentive may be offered for the employee’s own genetic information, including family medical history. |

| Family Member Provisions | The 30% limit applies to the employee’s participation. The rules are less explicit about incentives for family members’ participation in ADA-covered activities. | A limited incentive (historically up to 30% of self-only coverage) may be offered for a spouse’s health information, but not for information from children. |

| Core Principle | Ensuring that participation in a program requiring health disclosures is truly voluntary and not coerced by a large financial reward or penalty. | Protecting highly sensitive genetic and family medical data from being used for discriminatory purposes by strictly limiting financial inducements for its disclosure. |

Academic

A jurisprudential analysis of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s regulation of wellness program incentives under the ADA and GINA reveals a profound and persistent tension between two competing public policy objectives.

On one hand, the legislative and executive branches, particularly through the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the Affordable Care Act (ACA), have sought to promote employer-sponsored wellness programs as a mechanism for cost containment and public health improvement.

This policy is predicated on a behavioral economics model where financial incentives are deemed necessary to drive employee engagement. On the other hand, the EEOC, as the primary enforcement body for federal anti-discrimination statutes, is tasked with protecting employees from discriminatory practices and ensuring that any waiver of statutory protections, such as the right to keep medical information private, is done so knowingly and voluntarily.

The differing rules for ADA and GINA incentives are a direct result of the EEOC’s attempt to navigate this conflict, informed by the distinct statutory language and perceived sensitivity of the information each law protects.

The legal saga, particularly the case of AARP v. EEOC, represents a critical inflection point in this regulatory narrative. The D.C. District Court’s decision to vacate the EEOC’s 2016 regulations, which had attempted to harmonize the ADA incentive limit with the ACA’s 30% threshold, was a significant development.

The court’s reasoning was grounded in the Administrative Procedure Act, finding that the EEOC had failed to provide a reasoned explanation for how a 30% incentive level, which could amount to thousands of dollars in penalties for non-participation, could still be considered “voluntary” under the plain meaning of the ADA.

This judicial rebuke forced the EEOC back to the drawing board and signaled a deeper judicial skepticism toward the compatibility of large incentives with the foundational principles of anti-discrimination law. The subsequent, though now withdrawn, 2021 proposed rules with their “de minimis” standard can be viewed as a direct response to the court’s critique, representing a pendulum swing toward a more protective, rights-based interpretation of the statutes over the utilitarian, health-policy-driven approach of the ACA.

What Is the Statutory Basis for the Distinction?

The differential treatment of incentives under the ADA and GINA is rooted in the specific statutory exceptions provided in each law. The ADA’s relevant provision is the “voluntary medical examinations” exception. The statute itself does not define “voluntary,” leaving a significant gap for the EEOC to fill through regulation.

The Commission’s interpretation has been that voluntariness is compromised when an employer imposes a penalty or offers an incentive of a magnitude that would cause a reasonable person to feel compelled to participate and disclose medical information. The core of the ADA’s application here is the act of inquiry itself ∞ the biometric screening or the health risk assessment is the regulated event.

GINA’s statutory framework is structurally different and more rigid. Title II of GINA contains a general prohibition on employers requesting, requiring, or purchasing genetic information. The term “purchase” is critical, as it has been interpreted by the EEOC to include offering financial incentives for information.

GINA provides a narrow exception for voluntary “health or genetic services” offered by the employer. Crucially, the law distinguishes between an employee’s genetic information (including family medical history) and the “manifestation of a disease or disorder” in a family member.

The EEOC’s regulations have interpreted this to mean that an employer may “purchase” information about a spouse’s manifested disease (i.e. offer an incentive for it), but cannot “purchase” the employee’s family medical history. This statutory distinction provides a clear textual basis for the divergent incentive rules. The law itself creates a higher bar for obtaining information that is predictive and familial (genetic information) than for information that pertains to an individual’s current health status (disability-related inquiries).

The Economic and Ethical Dimensions

The debate over incentive levels is not merely a legalistic one; it has profound economic and ethical dimensions. Proponents of higher incentive limits, often from the business community, argue that wellness programs generate positive externalities. They contend that healthier employees lead to lower insurance claims, reduced absenteeism, and increased productivity, justifying the use of powerful financial inducements to maximize participation.

From this perspective, a “de minimis” incentive is functionally equivalent to no incentive, rendering the programs ineffective and squandering the potential for population-level health improvements.

Conversely, opponents, including disability rights and privacy advocates, raise significant ethical concerns. They argue that large incentives disproportionately impact lower-wage workers, creating a coercive environment where these employees cannot afford to refuse participation. This establishes a two-tiered system where higher-income employees can afford to safeguard their medical privacy, while lower-income employees are compelled to disclose it.

This raises issues of equity and justice. Furthermore, there is an ongoing academic debate about the actual efficacy of many workplace wellness programs, with some studies questioning whether they produce a positive return on investment or meaningful health outcomes. This uncertainty about their effectiveness weakens the utilitarian argument for permitting potentially coercive incentives.

The regulatory divergence between the ADA and GINA on wellness incentives reflects a fundamental legal and ethical distinction between protecting individuals from discrimination based on their current health status and the more stringent need to safeguard their immutable, predictive genetic data.

The issue is further complicated by the expanding definition of health data itself. As wearable technology and direct-to-consumer genetic testing become more commonplace, the lines between wellness, medical information, and genetic information are blurring. An employer-sponsored wellness challenge that uses data from a commercial fitness tracker could potentially collect information that implicates the ADA.

A program that encourages employees to explore their ancestry through a genetic testing service could inadvertently stray into the territory of GINA. The existing legal frameworks, drafted in a different technological era, are being stretched to their limits.

Future regulatory action will need to address these evolving technologies and the new forms of data they generate, likely requiring an even more sophisticated and nuanced approach to defining what constitutes a medical inquiry or a request for genetic information, and what makes participation in such data collection truly voluntary.

| Aspect | ADA Framework | GINA Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophical Basis | Protects against discrimination based on current or past health status (a mutable state). Focuses on equal opportunity and reasonable accommodation. | Protects against discrimination based on predictive, immutable genetic potential. Focuses on genetic privacy and the prevention of a “genetic underclass.” |

| Primary Legal Question | At what point does a financial incentive become coercive, rendering a “voluntary” program involuntary? | Does offering a financial incentive constitute an unlawful “purchase” of genetic information? |

| Nature of Information | Information about an individual’s current physical or mental condition (e.g. blood pressure, cholesterol, presence of a disorder). | Information about an individual’s genetic tests, family medical history, or the genetic tests of family members. |

| Regulatory Flexibility | The term “voluntary” allows for significant administrative interpretation, leading to fluctuating incentive limits (e.g. 30% vs. de minimis). | The statutory prohibition on “purchasing” genetic information provides less interpretive flexibility, leading to a near-total ban on incentives for such data. |

Ultimately, the divergence in incentive rules under the ADA and GINA is a legal recognition of a biological and social reality. Information about one’s current health status is sensitive, yet it is often a matter of degree and can be subject to change and management. Genetic information, however, carries a different weight.

It is probabilistic, familial, and permanent. The law, through the EEOC’s regulations, has effectively decided that the risk of discrimination based on this predictive genetic data is so great that almost no financial inducement can be permitted for its collection in the employment context.

The ADA’s rules, while still protective, allow for a more lenient standard because the information they govern, while personal, is seen as less determinative and less likely to lead to a form of genetic-based workplace stratification. The ongoing legal and regulatory developments in this area will continue to reflect society’s evolving understanding of the relationship between health, data, privacy, and equality.

References

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. “Final Rule on Employer Wellness Programs and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act.” Federal Register, vol. 81, no. 96, 17 May 2016, pp. 31143-31156.

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. “Final Rule on Employer Wellness Programs and the Americans with Disabilities Act.” Federal Register, vol. 81, no. 96, 17 May 2016, pp. 31125-31142.

- Hudson, K. L. “Genomics, Health Care, and Society.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 365, no. 11, 2011, pp. 1033-1041.

- Madison, Kristin M. “The Law and Policy of Workplace Wellness Programs ∞ A Critical Assessment.” Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, vol. 44, no. 1, 2016, pp. 79-93.

- AARP v. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 267 F. Supp. 3d 14 (D.D.C. 2017).

- Schmidt, Harald, and George L. Wehby. “The Ethics of Health-Contingent Wellness Incentives ∞ What’s the Harm?” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 107, no. 1, 2017, pp. 62-65.

- Song, Zirui, and Katherine Baicker. “Effect of a Workplace Wellness Program on Employee Health and Economic Outcomes ∞ A Randomized Clinical Trial.” JAMA, vol. 321, no. 15, 2019, pp. 1491-1501.

- The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008, Pub. L. No. 110-233, 122 Stat. 881.

- The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, Pub. L. No. 101-336, 104 Stat. 327.

- Bagenstos, Samuel R. “The Future of Disability Law.” Yale Law Journal, vol. 114, no. 1, 2004, pp. 1-84.

Reflection

The intricate rules governing wellness programs are more than administrative hurdles. They represent a societal conversation about the value we place on personal health data. As you continue on your path to understanding and optimizing your own biological systems, consider the nature of the information you gather.

Each lab value, each biometric measurement, and each piece of family health history is a data point in the story of you. These regulations prompt a deeper question ∞ What is the appropriate relationship between your personal health narrative and your professional life?

The knowledge of these legal boundaries is a tool, one that allows you to engage with wellness initiatives confidently, making informed choices that align with your personal health philosophy and your right to privacy. Your journey is your own; this understanding ensures you remain its sole author.

Glossary

workplace wellness programs

genetic information nondiscrimination act

americans with disabilities act

wellness program

personal health

health information

ada and gina

employee health

equal employment opportunity commission

genetic information nondiscrimination

genetic information

family medical history

health insurance

health risk assessment

wellness programs

genetic data

including family medical history

wellness incentives

incentive limits

medical inquiry

biometric screening

risk assessment

voluntary participation

health-contingent programs

participatory programs

reasonable alternative standard must

withdrawn 2021 proposed rules

de minimis incentive

wellness program that includes

wellness program incentives

aarp v. eeoc

workplace wellness