Fundamentals

The Biology of Overwhelm

You feel it in your bones. The persistent fatigue that sleep does not seem to touch. The subtle but steady thickening around your waistline, even when your diet has not dramatically changed. A sense of being perpetually “on,” wired and tired, is a common narrative in modern life.

This experience is not a personal failing or a lack of discipline. It is a physiological reality rooted in the body’s ancient survival systems meeting the demands of a relentless world. Your body is having a biological conversation, and the language it is speaking is hormonal. Understanding this language is the first step toward reclaiming your metabolic health.

At the center of this conversation is the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. Think of this as your body’s internal emergency response system. When your brain perceives a threat ∞ be it a looming work deadline, financial worry, or emotional distress ∞ it triggers a chemical cascade.

The hypothalamus signals the pituitary gland, which in turn signals the adrenal glands, located atop your kidneys, to release a surge of hormones. The most prominent of these is cortisol. In short bursts, cortisol is incredibly useful. It sharpens your focus, mobilizes energy by increasing blood sugar, and primes your body for immediate action. This is the “fight or flight” response, a brilliant evolutionary adaptation for short-term survival.

When the Alarm Never Turns Off

The challenge for long-term health arises when the alarm system is never fully disarmed. Our bodies are not designed for the low-grade, chronic activation that defines much of contemporary stress. When the HPA axis is constantly stimulated, cortisol levels remain persistently elevated. This sustained exposure begins to systematically disrupt your metabolic machinery.

The very hormone that is meant to save you in an acute crisis starts to create a chronic one. This process is subtle, unfolding over years, and its effects are profound, touching nearly every aspect of your body’s ability to manage energy.

The body’s response to chronic stress is a key driver of metabolic dysregulation, turning a short-term survival mechanism into a long-term health liability.

One of the first systems to be affected is your body’s management of blood sugar. Cortisol’s primary job in a crisis is to ensure you have plenty of fuel. It does this by promoting gluconeogenesis, a process where the liver creates glucose from non-carbohydrate sources, like amino acids from your muscle tissue.

Simultaneously, it can decrease the sensitivity of your cells to insulin, the hormone responsible for ushering glucose out of the bloodstream and into cells for use. When this state of high alert becomes the new normal, your cells become progressively less responsive to insulin’s signals. This condition, known as insulin resistance, forces the pancreas to work harder, producing more and more insulin to try and manage blood sugar levels. This is a foundational step toward a host of metabolic complications.

How Stress Changes Your Physical Form

The metabolic consequences of chronically high cortisol extend to how and where your body stores energy. Elevated cortisol levels are strongly linked to an increase in appetite, particularly for foods that are high in sugar and fat. This is a primal drive for calorie-dense fuel to manage the perceived threat.

This hormonal signal can override even the most disciplined eating habits. The body under chronic stress is not just storing more fat; it is storing it in a specific, and more dangerous, location. Cortisol preferentially promotes the accumulation of visceral adipose tissue (VAT), the deep abdominal fat that surrounds your internal organs.

This type of fat is metabolically active, functioning almost like an endocrine organ itself. It releases inflammatory proteins and further disrupts hormonal signaling, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of metabolic dysfunction.

This cascade of events ∞ HPA axis activation, sustained cortisol release, insulin resistance, and visceral fat storage ∞ forms the biological basis for what many people experience as an inexplicable struggle with their weight and energy levels. It is a physiological process, not a personal shortcoming. Recognizing the profound influence of your stress response system on your metabolic health is the essential starting point for developing a strategy to restore balance and vitality.

Intermediate

The Cortisol-Insulin Antagonism

To comprehend the long-term metabolic consequences of stress, we must examine the intricate relationship between cortisol and insulin. These two hormones have counter-regulatory functions concerning blood glucose. Insulin’s primary role is to lower blood glucose after a meal by facilitating its uptake into muscle, liver, and fat cells.

Cortisol, when chronically elevated, actively works against this process. It ensures energy availability by keeping blood glucose levels high. This creates a state of functional insulin resistance, where the body’s cells become less sensitive to insulin’s signals. The pancreas compensates by secreting even more insulin, leading to a condition called hyperinsulinemia. This sustained high level of both cortisol and insulin is a potent driver of metabolic disease.

This hormonal conflict has several downstream consequences. The persistent demand on the pancreas can eventually lead to beta-cell exhaustion, impairing its ability to produce sufficient insulin and potentially culminating in type 2 diabetes. Moreover, high insulin levels are a powerful signal for fat storage.

When combined with cortisol’s tendency to promote visceral fat, the result is a significant alteration of body composition and an increased risk for cardiovascular disease. Understanding this dynamic is central to any clinical protocol aimed at restoring metabolic health. The goal is to reduce the allostatic load on the body, allowing the HPA axis to return to a state of equilibrium and resensitizing cells to insulin’s effects.

Clinical Manifestations of Chronic Stress

The systemic impact of HPA axis dysfunction presents in ways that can be measured and tracked through clinical assessment. These biomarkers provide an objective window into the body’s internal state, moving beyond subjective feelings of stress. A comprehensive evaluation often reveals a characteristic pattern of metabolic dysregulation.

- Dyslipidemia ∞ Chronic stress frequently alters blood lipid profiles. This typically involves elevated triglycerides, lowered high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and sometimes elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. This pattern is a direct consequence of insulin resistance and the liver’s response to excess circulating glucose and fatty acids.

- Hypertension ∞ Stress hormones, including adrenaline and cortisol, directly influence blood pressure. Acute stress causes a temporary spike. Chronic activation of the stress response system contributes to sustained hypertension, a major risk factor for cardiovascular events.

- Muscle Catabolism ∞ As part of its function to raise blood glucose, cortisol can promote the breakdown of muscle protein to provide amino acids for gluconeogenesis in the liver. Over time, this can lead to a reduction in lean muscle mass, which further slows the metabolic rate and worsens insulin resistance.

The interplay between elevated cortisol and insulin resistance creates a vicious cycle that degrades metabolic health and alters body composition.

These clinical signs are not isolated issues. They are interconnected components of what is often termed metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions that significantly increases the risk of developing heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes. The presence of chronic stress acts as a powerful accelerator for the development and progression of this syndrome. Therefore, therapeutic interventions must address the root cause ∞ the dysregulated stress response ∞ in addition to managing the individual symptoms.

Hormonal Optimization in a High-Stress Context

When individuals seek solutions for symptoms like fatigue, weight gain, and low libido, it is essential to evaluate their metabolic health within the context of their stress levels. Hormonal optimization protocols, such as Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) for men and women, can be highly effective, but their success is deeply intertwined with HPA axis function.

Chronic stress can suppress the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, the system that governs sex hormone production. Elevated cortisol can interfere with the production of testosterone and other vital hormones.

For a middle-aged man experiencing symptoms of low testosterone, a standard protocol might involve weekly injections of Testosterone Cypionate. This is often combined with agents like Gonadorelin to maintain testicular function and Anastrozole to manage estrogen levels. However, if this patient also has high levels of chronic stress and elevated cortisol, the full benefits of TRT may be blunted.

The underlying metabolic disruption caused by cortisol can continue to cause issues. A comprehensive approach would involve both restoring testosterone levels and implementing strategies to mitigate the stress response, such as lifestyle modifications, nutritional support, and potentially adaptogenic supplements or peptide therapies designed to support HPA axis resilience.

Comparing Metabolic Effects of Key Hormones

The following table illustrates the contrasting effects of key hormones on metabolic processes, highlighting the disruptive influence of chronically elevated cortisol.

| Hormone | Primary Metabolic Function | Effect on Blood Glucose | Effect on Fat Storage | Effect on Muscle Mass |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin | Promotes energy storage | Lowers | Increases | Promotes synthesis |

| Cortisol (Chronic High) | Promotes energy mobilization for stress | Raises | Increases (especially visceral) | Promotes breakdown (catabolic) |

| Testosterone | Promotes anabolic processes | Improves insulin sensitivity | Decreases (especially visceral) | Promotes synthesis (anabolic) |

| Growth Hormone Peptides (e.g. Sermorelin) | Stimulates growth and cell reproduction | Can initially raise, but improves long-term sensitivity | Decreases | Promotes synthesis (anabolic) |

This table clarifies why simply addressing one hormonal deficiency may not be sufficient if the broader metabolic environment is compromised by stress. For instance, the anabolic, muscle-building effects of testosterone and growth hormone peptides are directly opposed by the catabolic effects of high cortisol. Achieving optimal outcomes requires a systems-based approach that recognizes and addresses these interconnected hormonal pathways.

Academic

Glucocorticoid Receptor Signaling and Metabolic Pathophysiology

The biological actions of cortisol are mediated by the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily that functions as a ligand-dependent transcription factor. When cortisol binds to the GR in the cytoplasm, the receptor translocates to the nucleus, where it can either activate or repress gene expression.

This genomic signaling pathway is responsible for the majority of cortisol’s metabolic effects, including the regulation of enzymes involved in gluconeogenesis and lipolysis. The sensitivity of tissues to cortisol is a critical determinant of metabolic health. Chronic exposure to high levels of cortisol can lead to a complex and tissue-specific dysregulation of GR signaling.

This can manifest as glucocorticoid resistance in some tissues (like the immune system) while other tissues, particularly visceral adipose tissue, may remain highly sensitive or even become hypersensitive. This differential sensitivity contributes significantly to the pathophysiology of metabolic syndrome.

In the liver, cortisol-activated GR signaling upregulates the expression of key gluconeogenic enzymes such as phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) and glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase). This drives hepatic glucose production. In skeletal muscle, cortisol promotes protein degradation, releasing amino acids that serve as substrates for this process. In adipose tissue, the effects are more complex.

While cortisol can promote lipolysis to release fatty acids for energy, its chronic presence, especially in conjunction with high insulin, powerfully stimulates the differentiation of preadipocytes into mature fat cells and promotes lipid accumulation, particularly in visceral depots. This visceral adiposity is a locus of low-grade inflammation, releasing adipokines that further exacerbate insulin resistance systemically.

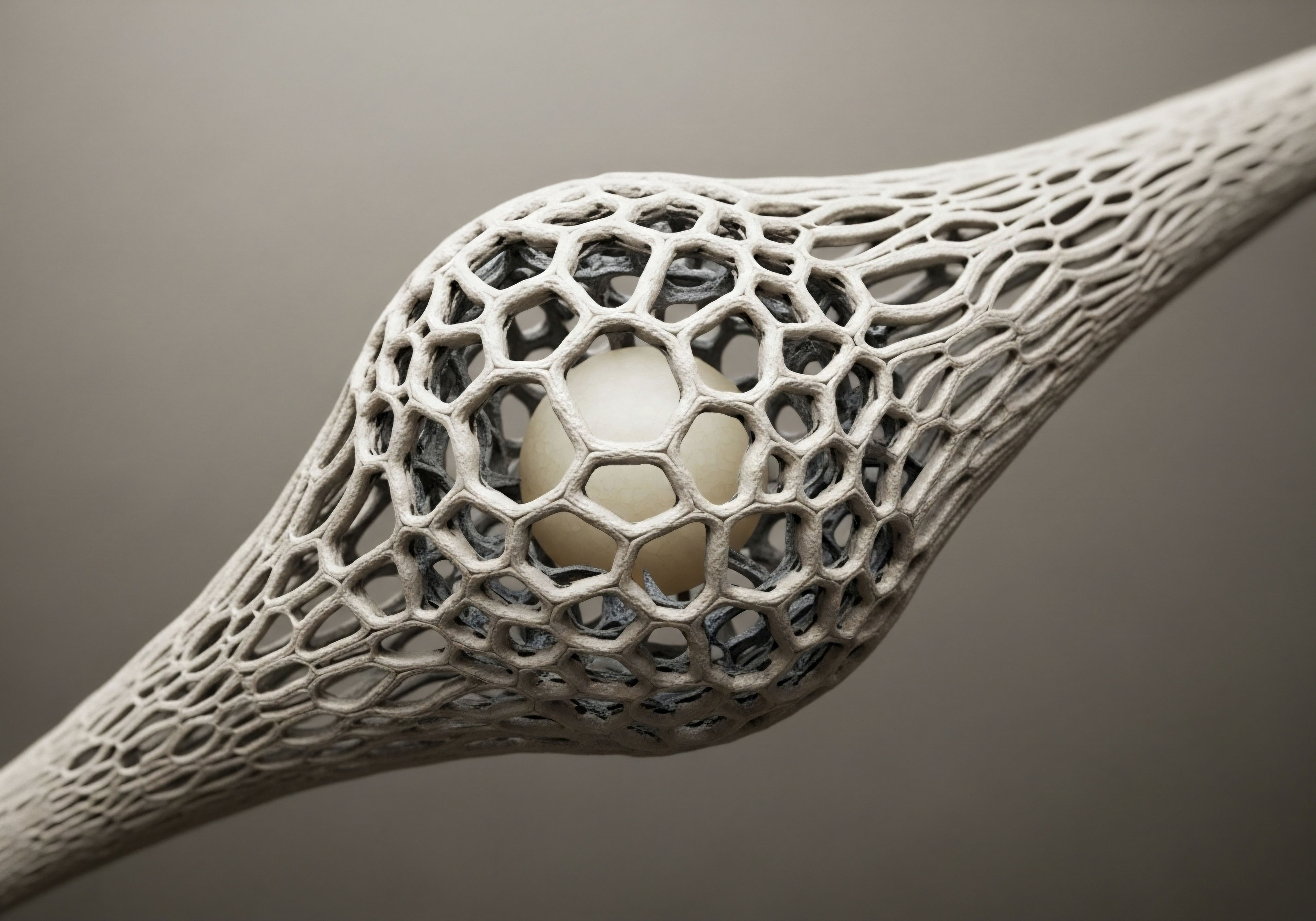

What Is the Role of 11β-HSD1 in Tissue-Specific Cortisol Action?

The local concentration of active cortisol within specific tissues is not solely dependent on circulating levels. It is tightly regulated by the enzyme 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (11β-HSD1). This enzyme is highly expressed in key metabolic tissues, including the liver and adipose tissue.

Its primary function is to convert inactive cortisone into active cortisol, thereby amplifying glucocorticoid action locally. Overexpression or increased activity of 11β-HSD1 in adipose tissue has been strongly implicated in the pathogenesis of central obesity and metabolic syndrome. Even with normal circulating cortisol levels, elevated local conversion within fat cells can drive visceral fat accumulation and insulin resistance.

This mechanism provides a crucial link between the systemic stress response and tissue-specific metabolic dysfunction. Therapeutic strategies targeting the inhibition of 11β-HSD1 have been an area of intense research for the treatment of type 2 diabetes and obesity, underscoring the importance of this enzymatic control point.

Tissue-specific regulation of cortisol activity, particularly by the enzyme 11β-HSD1, is a key determinant in the development of visceral obesity and insulin resistance.

The interplay between systemic cortisol levels and local enzymatic regulation creates a complex picture. For example, a person might exhibit laboratory tests showing cortisol levels within the normal range, yet still suffer from the metabolic consequences of glucocorticoid excess due to heightened 11β-HSD1 activity in their visceral fat.

This highlights the limitations of relying solely on serum cortisol measurements and emphasizes the importance of assessing the clinical picture, including body composition and markers of insulin resistance, to understand an individual’s metabolic health status.

Interplay of HPA, HPG, and HPT Axes

A systems-biology perspective reveals that the HPA axis does not operate in isolation. Its chronic activation has profound inhibitory effects on other critical endocrine axes, namely the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) axis. This crosstalk is a primary mechanism through which chronic stress degrades overall health and vitality.

- HPA-HPG Interaction ∞ Elevated levels of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and cortisol can suppress the release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus. This, in turn, reduces the pituitary’s secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), leading to decreased production of testosterone in men and estrogen in women. This explains the common clinical findings of low libido, reproductive dysfunction, and symptoms of hypogonadism in individuals under significant chronic stress.

- HPA-HPT Interaction ∞ Chronic stress can also impair thyroid function. Cortisol can inhibit the conversion of inactive thyroxine (T4) to active triiodothyronine (T3) in peripheral tissues. It can also increase the conversion of T4 to reverse T3 (rT3), an inactive metabolite. The resulting decrease in active thyroid hormone can slow the metabolic rate, contributing to fatigue, weight gain, and cognitive sluggishness, further compounding the metabolic disruption caused directly by cortisol.

Key Mediators in Endocrine Axis Crosstalk

The following table outlines the key hormones and their roles in the interconnected stress, reproductive, and thyroid axes.

| Axis | Key Hypothalamic Hormone | Key Pituitary Hormone | Key End-Organ Hormone | Effect of Chronic HPA Activation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPA (Stress) | CRH | ACTH | Cortisol | Becomes chronically activated |

| HPG (Gonadal) | GnRH | LH / FSH | Testosterone / Estrogen | Suppressed at hypothalamic and pituitary levels |

| HPT (Thyroid) | TRH | TSH | T3 / T4 | Impaired T4 to T3 conversion; increased rT3 |

This integrated view is essential for effective clinical intervention. A patient presenting with symptoms of hypogonadism and hypothyroidism may have a primary issue within those systems. It is also possible that these are downstream consequences of chronic HPA axis activation. A successful therapeutic strategy must identify and address the primary driver of the dysfunction.

In many cases, this involves a dual approach ∞ supporting the suppressed HPG and HPT axes through appropriate hormonal protocols while simultaneously implementing measures to down-regulate the overactive stress response system. This might include peptide therapies like Sermorelin or Ipamorelin/CJC-1295, which can support anabolic processes and improve sleep quality, thereby helping to restore a more favorable overall hormonal balance.

References

- Hewagalamulage, S. D. Lee, T. K. Clarke, I. J. & Breen, E. J. (2016). Stress, cortisol, and obesity ∞ a role for cortisol responsiveness in identifying individuals prone to obesity. Domestic Animal Endocrinology, 56, S112-S120.

- Adam, T. C. & Epel, E. S. (2007). Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiology & Behavior, 91(4), 449-458.

- An, Y. & An, W. (2020). Glucocorticoids and the metabolic syndrome. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 196, 105505.

- Thau, L. Gandhi, J. & Sharma, S. (2021). Physiology, Cortisol. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- Kyrou, I. Chrousos, G. P. & Tsigos, C. (2006). Stress, weight gain and the endocannabinoid system. Endocrinology and Metabolism, 2(3), 1-8.

- Bjorntorp, P. (2001). Do stress reactions cause abdominal obesity and comorbidities?. Obesity Reviews, 2(2), 73-86.

- Pasquali, R. Vicennati, V. Cacciari, M. & Pagotto, U. (2006). The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in obesity. International Journal of Obesity, 30(S4), S14-S17.

- Pivonello, R. Patalano, R. De Martino, M. C. & Colao, A. (2011). Glucocorticoid-induced insulin resistance. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, 34(7 Suppl), 21-25.

- Chapman, K. E. Seckl, J. R. & Walker, B. R. (2013). 11β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 and its role in the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 27(3), 381-393.

- Whirledge, S. & Cidlowski, J. A. (2010). Glucocorticoids, stress, and fertility. Minerva Endocrinologica, 35(2), 109-125.

Reflection

Recalibrating Your Internal Compass

The information presented here offers a biological map, tracing the pathways from the feeling of being stressed to the measurable changes in your metabolic health. This knowledge provides a powerful framework for understanding your own body’s signals. The fatigue, the changes in body composition, the persistent sense of being overwhelmed ∞ these are not abstract complaints.

They are data points. They tell a story of a system working hard to protect you, a system that may now require intentional support to find its way back to balance.

Consider the patterns in your own life. Think about the periods of prolonged pressure and how your body felt during and after those times. This personal history, when viewed through the lens of endocrinology and metabolic science, becomes an invaluable tool.

It allows you to move from a position of reacting to symptoms to one of proactively managing the underlying systems. The journey to reclaiming your vitality begins with this shift in perspective. It starts with the recognition that you have the capacity to understand and influence the intricate, intelligent systems that govern your health.