Fundamentals

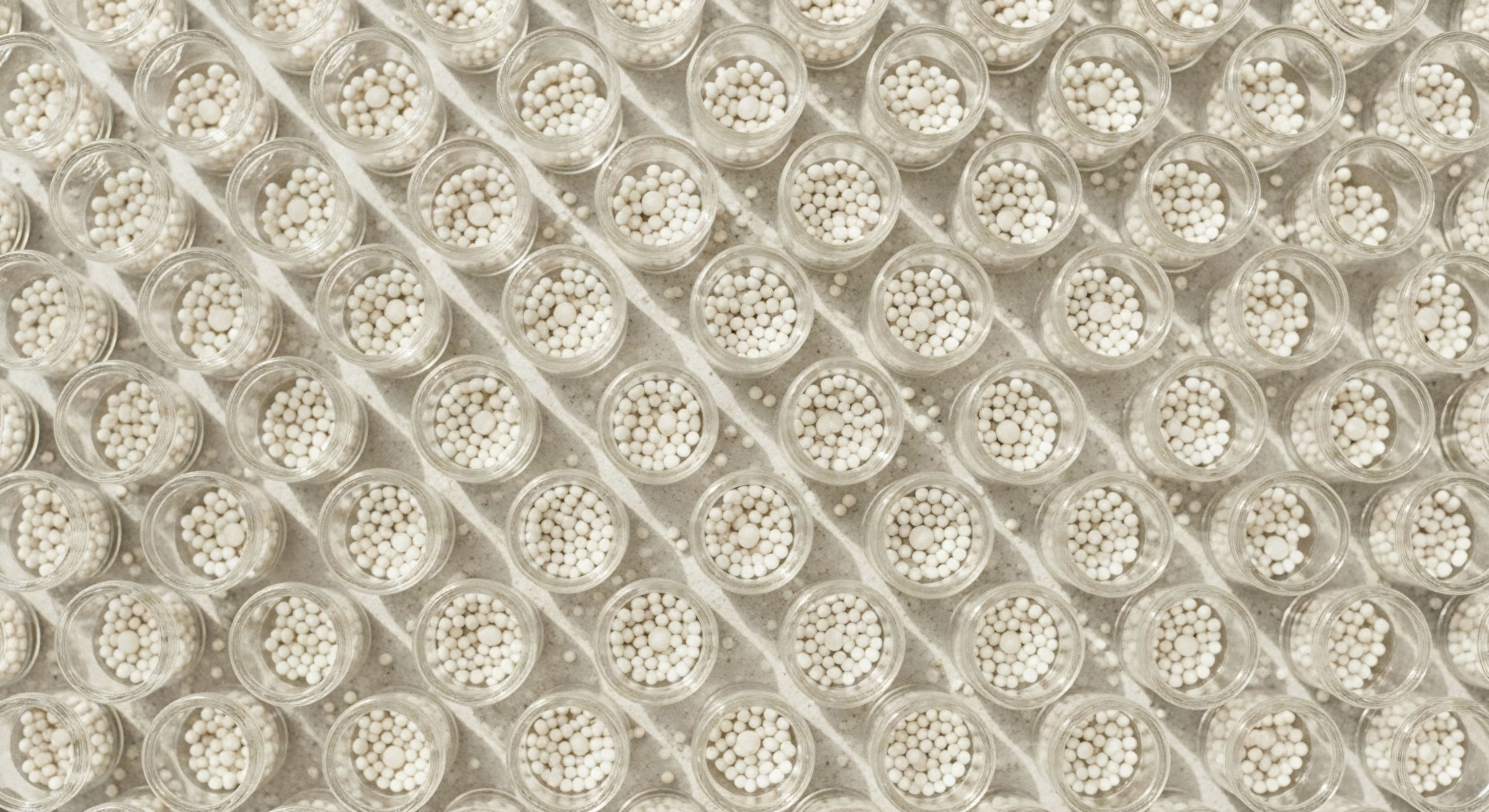

You hold in your hands a small vial, often cool to the touch. Inside rests a lyophilized powder, a substance that feels both clinical and full of potential. This is the starting point of a protocol designed to communicate with your body on a molecular level.

The instructions for reconstitution and storage are precise for a very specific reason. The peptide within that vial is a carefully constructed message, a key designed to fit a specific lock within your cells. The entire purpose of meticulous storage is to protect the integrity of that key, ensuring that when it reaches its destination, it can turn the lock as intended. Its efficacy is a direct extension of its physical structure.

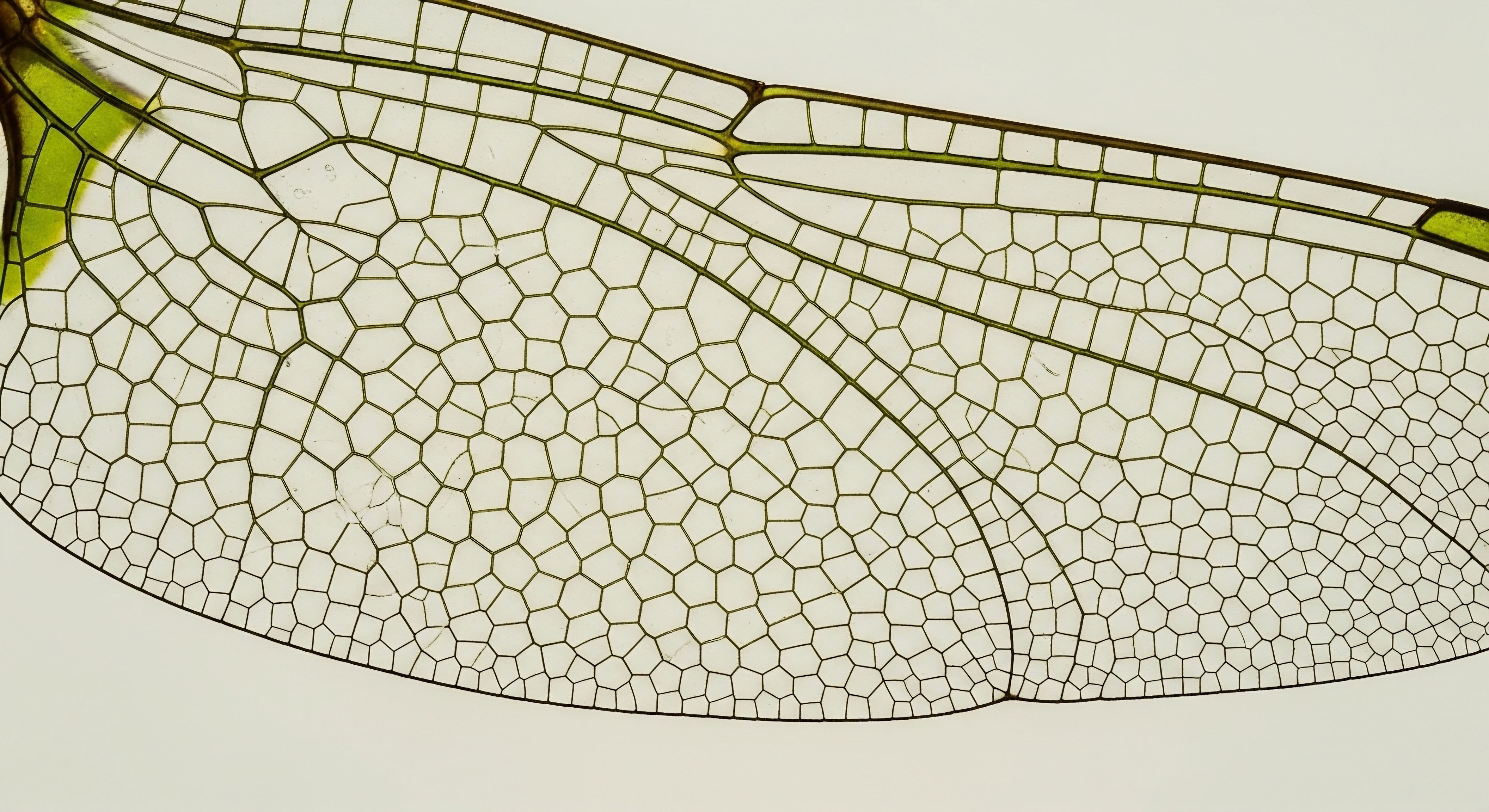

Think of a peptide as a delicate, three-dimensional piece of origami. Its folds and shape are what give it meaning and function. When that shape is compromised, the message it carries becomes garbled. The primary forces that can unfold this delicate structure are environmental.

Temperature, light, moisture, and even air itself are powerful agents of change at this microscopic scale. Understanding their influence is the first step in safeguarding the potential held within each vial and ensuring your protocol can deliver its intended biological outcome.

The Primary Guardian Temperature

Heat is a form of energy. When introduced to a peptide solution, this energy causes molecules to vibrate more rapidly. This molecular agitation can be strong enough to break the weak bonds that hold the peptide in its specific three-dimensional shape. The process is called denaturation.

A denatured peptide is like a key that has been bent out of shape; it will no longer fit the receptor it was designed for. This is why refrigeration or freezing is the universal standard for peptide storage. Lowering the temperature slows down molecular motion, preserving the peptide’s structure for a longer duration.

The lyophilized, or freeze-dried, state offers the highest degree of stability because the absence of water prevents many degradation pathways from occurring. Once you add bacteriostatic water to reconstitute the peptide, it becomes much more vulnerable. It is now in a liquid environment where molecules can move freely and interact.

The refrigerator becomes its sanctuary, a low-energy environment that protects its structure between administrations. Repeated freeze-thaw cycles should be avoided, as the formation of ice crystals can physically damage the peptides, shearing them apart. Aliquoting, or dividing the reconstituted solution into smaller, single-use portions, is a practical strategy to prevent this.

A peptide’s therapeutic power is directly linked to the preservation of its precise molecular shape.

The Role of Light and Air

Peptides, particularly those with certain amino acids in their sequence, can be sensitive to ultraviolet (UV) light. The energy from UV radiation can directly break chemical bonds or promote oxidation, another form of degradation. This is why many peptides are shipped in amber or opaque vials.

Storing them in a dark place, such as the box they came in, inside a refrigerator, provides an additional layer of protection. It is a simple step that shields the molecules from this external energetic assault.

Oxygen in the air is also a reactive molecule. Oxidation can alter specific amino acid side chains, particularly methionine and cysteine. This chemical change modifies the peptide’s structure and, consequently, its function. While lyophilized powders are relatively safe, once a peptide is in solution, minimizing its exposure to air is beneficial.

This is accomplished by keeping the vial sealed, reconstituting it swiftly, and storing it properly. Each of these storage parameters works in concert to maintain the peptide’s structural integrity from the moment it is reconstituted to the moment it is administered.

- Temperature ∞ Store lyophilized peptides at ∞ 20°C for long-term stability. Once reconstituted, store in a refrigerator at around 2-8°C.

- Light ∞ Keep peptides in their original amber or dark vials and store them in a box or dark area to prevent degradation from UV exposure.

- Moisture ∞ The lyophilized state is protective. Once reconstituted with water, the peptide is more susceptible to hydrolysis.

- Handling ∞ Avoid shaking the vial vigorously, as this can physically damage the peptide structure. Gentle swirling is sufficient for mixing.

Intermediate

The general principles of proper storage ∞ keeping peptides cool, dark, and sealed ∞ provide a solid foundation for preserving their function. Advancing your understanding requires a look into the specific chemical reactions that these conditions are designed to prevent. Peptide degradation is a biochemical process.

It follows predictable pathways that alter the covalent bonds of the molecule, creating new chemical entities that lack the efficacy of the original peptide. These pathways are the “how” behind a peptide losing its potency. By examining them, we move from following rules to understanding the molecular logic that underpins them.

The three primary chemical degradation pathways are hydrolysis, oxidation, and deamidation. Each one targets different weak points within the peptide’s amino acid sequence and is accelerated by specific environmental conditions. A peptide’s susceptibility is determined by its unique composition.

For instance, a peptide rich in aspartic acid may be particularly vulnerable to hydrolysis, while one containing multiple cysteine residues is more prone to oxidation. This is why storage guidelines are so stringent; they represent a generalized defense against these ubiquitous chemical threats.

Hydrolysis the Unraveling by Water

Hydrolysis is the chemical breakdown of a compound due to reaction with water. In the context of peptides, this typically involves the cleavage of the peptide backbone itself. This breaks the chain of amino acids, effectively destroying the peptide. This process is highly dependent on pH.

Acidic or alkaline conditions can significantly accelerate the rate of hydrolysis. This is a primary reason why reconstituted peptides have a much shorter shelf-life than their lyophilized counterparts. The presence of water itself makes hydrolysis possible.

A specific form of hydrolysis targets sequences containing an aspartic acid (Asp) residue. The side chain of aspartic acid can attack the peptide backbone, forming a cyclic succinimide intermediate. This intermediate is then rapidly hydrolyzed by water, which can result in either the original aspartic acid residue or, more problematically, an isoaspartic acid residue.

This isomerization creates a kink in the peptide backbone, altering its three-dimensional shape and reducing its ability to bind to its target receptor. This single, small chemical change can have a substantial impact on biological activity.

What Are the Consequences of Using Degraded Peptides in China?

The regulatory landscape for peptides in any country, including China, adds another layer of complexity to their use. When peptides are imported or transported under suboptimal conditions, their degradation is accelerated. Using a degraded peptide means you are administering a substance with reduced or absent therapeutic activity.

This leads to a lack of results and can cause confusion about the efficacy of a given protocol. Instead of achieving the desired physiological response, such as the release of growth hormone stimulated by Sermorelin, the body receives a molecule that cannot perform its function. This translates to wasted time, effort, and financial investment in a therapeutic regimen.

From a clinical standpoint, the consequences extend beyond a simple lack of effect. The breakdown products of a peptide are new chemical entities. While many may be inert, some have the potential to be immunogenic, meaning they could trigger an immune response.

The body might recognize these altered peptide fragments as foreign invaders, leading to the production of antibodies. This could, in a theoretical scenario, cause a reaction to the correctly structured peptide in the future. Ensuring a peptide’s integrity through an unbroken “cold chain” from manufacturing to administration is therefore a matter of both efficacy and safety.

The stability of a reconstituted peptide is a countdown clock, with each environmental exposure accelerating the degradation process.

Oxidation and Deamidation Subtle Changes

Oxidation is a chemical reaction that involves the loss of electrons. For peptides, the amino acids most susceptible to this process are methionine (Met) and cysteine (Cys). Exposure to atmospheric oxygen, especially in a liquid solution, can convert a methionine residue to methionine sulfoxide.

A cysteine residue can be oxidized to form a disulfide bond with another cysteine residue, either within the same chain or by linking two separate peptide molecules together. This dimerization creates a much larger molecule that will not be recognized by the target receptor. These oxidative changes alter the chemical properties and shape of the peptide, diminishing its biological function.

Deamidation is a reaction that affects asparagine (Asn) and glutamine (Gln) residues. It involves the removal of an amide group from the side chain. For asparagine, this process is particularly common, especially if it is followed by a glycine (Gly) residue in the sequence.

The reaction proceeds through a cyclic imide intermediate, similar to the one seen in aspartic acid isomerization, and results in the conversion of asparagine to either aspartic acid or isoaspartic acid. This introduces a negative charge into a previously neutral part of the molecule, which can disrupt the folding and binding affinity of the peptide. N-terminal glutamine residues can also cyclize to form pyroglutamic acid, a modification that can block the peptide’s activity.

| Peptide Type | Lyophilized Stability (at -20°C) | Reconstituted Stability (at 2-8°C) | Primary Degradation Vulnerability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sermorelin / Ipamorelin | Up to 12 months | 30-60 days | Hydrolysis of the peptide backbone |

| BPC-157 (PDA) | Up to 24 months | Up to 6 months (highly stable) | Less susceptible than many other peptides |

| CJC-1295 | Up to 12 months | 30-90 days | Deamidation, particularly of asparagine residues |

| PT-141 | Up to 12 months | 60-90 days | Oxidation and cyclization |

Academic

An academic examination of peptide stability moves beyond storage guidelines and into the realms of chemical kinetics, molecular biophysics, and immunology. The efficacy of a peptide therapeutic is a direct function of its concentration in a biologically active conformation at the site of action.

Storage conditions are the primary determinant of the initial concentration of active peptide. Any degradation that occurs before administration represents a loss of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), which will proportionally decrease the achievable therapeutic effect. The relationship between storage and efficacy is therefore a question of preserving molecular integrity to ensure predictable pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.

The degradation of a peptide is not an instantaneous event. It is a process that occurs over time, and its rate can be modeled using chemical kinetics. The rate of degradation is influenced by temperature, pH, light exposure, and the presence of catalysts.

For example, the hydrolysis of the peptide backbone often follows first-order kinetics, meaning the rate of degradation is directly proportional to the concentration of the peptide. Understanding these reaction rates allows for the prediction of a peptide’s shelf-life under various conditions and informs the development of more stable formulations.

Molecular Integrity and Receptor Affinity

The interaction between a peptide and its receptor is governed by the principles of molecular recognition. The peptide’s three-dimensional structure, or tertiary structure, creates a specific surface with a unique distribution of charge, hydrophobicity, and hydrogen-bonding potential. This surface is complementary to the binding pocket of its target receptor. The binding affinity, a measure of how tightly the peptide binds to the receptor, is highly sensitive to even minor structural perturbations.

Degradation pathways introduce such perturbations. The isomerization of an aspartic acid residue to isoaspartic acid, for example, introduces a methylene group into the peptide backbone, creating a “kink” that disrupts the local conformation. This can drastically reduce binding affinity.

Similarly, the oxidation of a methionine residue to methionine sulfoxide introduces a polar, bulky group that can sterically hinder the peptide from fitting into the receptor’s binding pocket. A degraded peptide may therefore be present in the bloodstream but is unable to effectively signal the cell because it cannot properly dock with its receptor. Its biological message is lost due to a failure in the physical interface.

Every degradation event reduces the population of effective molecules available to produce a biological response.

How Do Chinese Regulations Impact Peptide Import and Storage?

The importation of therapeutic peptides into any country, including China, is subject to stringent regulations governed by agencies analogous to the FDA. These regulations are designed to ensure the safety, purity, and potency of all pharmaceutical agents. A critical component of this regulatory framework is the control over the supply chain, often referred to as Good Distribution Practices (GDP).

GDP mandates that all pharmaceuticals are stored and transported under conditions that prevent degradation. For peptides, this almost universally requires an unbroken cold chain, where the product is maintained within a specific temperature range (e.g. 2-8°C) from the manufacturer to the end user.

Any deviation in this cold chain, which can be monitored by temperature-logging devices, can be grounds for a shipment being rejected by customs or regulatory bodies. This has direct commercial implications for suppliers and can cause significant delays for patients. The documentation required to prove an unbroken cold chain is extensive.

For individuals importing peptides for personal use, navigating these regulations can be exceptionally challenging. The risk of a shipment being held at customs at ambient temperature for an extended period is high, which would almost certainly lead to significant degradation and a complete loss of efficacy.

Can Third Party Testing Verify Peptide Potency after Shipment?

Yes, third-party analytical laboratories can be contracted to verify the potency and purity of a peptide sample. The gold standard technique for this is High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) coupled with Mass Spectrometry (MS). HPLC separates the components of a sample based on their chemical properties.

In a pure, undegraded peptide sample, the HPLC chromatogram will show a single, large peak at a specific retention time. If the peptide has degraded, the chromatogram will show the main peak being smaller, with additional peaks appearing that correspond to the degradation products.

Mass Spectrometry then analyzes the mass-to-charge ratio of the molecules in each peak. This allows for the precise identification of the original peptide and its degradation products. For example, MS can differentiate between a peptide with an asparagine residue and one where that residue has been deamidated to aspartic acid, as there will be a one-dalton mass difference.

This level of analysis provides a definitive quantitative assessment of a peptide’s purity and can confirm the percentage of active, intact peptide remaining in a vial. This type of testing is expensive but provides the highest level of assurance regarding a product’s integrity after it has been shipped or stored for a period of time.

| Amino Acid Residue | Degradation Pathway | Chemical Consequence | Accelerated By |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspartic Acid (Asp) | Isomerization | Forms a cyclic imide intermediate, leading to isoaspartic acid. | Acidic or basic pH, presence of water. |

| Asparagine (Asn) | Deamidation | Forms a cyclic imide intermediate, leading to aspartic or isoaspartic acid. | Neutral to basic pH, specific neighboring residues (e.g. Glycine). |

| Glutamine (Gln) | Pyroglutamate Formation | N-terminal Gln cyclizes, removing the N-terminal amine group. | Acidic conditions, heat. |

| Methionine (Met) | Oxidation | Forms methionine sulfoxide or sulfone. | Oxygen, metal ions, light. |

| Cysteine (Cys) | Oxidation | Forms disulfide bonds (dimerization) or sulfonic acid. | Oxygen, higher pH, metal ions. |

| Tryptophan (Trp) | Oxidation | Forms various oxidation products, including kynurenine. | Oxygen, light, peroxide contaminants. |

References

- Sigma-Aldrich. “Peptide Stability and Potential Degradation Pathways.” MilliporeSigma, Accessed July 25, 2025.

- Acedo, J.Z. et al. “Instability of Peptide and Possible Causes of Degradation.” Encyclopedia, vol. 3, no. 1, 2023, pp. 339-357.

- “Do Peptides Degrade Over Time.” Peptide Sciences, Accessed July 25, 2025.

- Al-Ghananeem, A.M. and Malkawi, A.H. “Strategies for Improving Peptide Stability and Delivery.” Pharmaceuticals, vol. 15, no. 10, 2022, p. 1289.

- Patel, J. “Peptides and probable degradation pathways.” SlideShare, Uploaded 12 May 2015.

Reflection

The knowledge of how a peptide’s environment dictates its function is more than an academic exercise. It is a form of stewardship over your own therapeutic protocol. Each step you take, from the moment you open the shipping container to the careful reconstitution and daily storage, is an active participation in your health journey.

You are the guardian of this molecular information. This detailed understanding transforms the simple act of storing a vial in the refrigerator into a conscious decision to protect the potential for biological change.

This information serves as a map, showing you the forces that can diminish the efficacy of these powerful tools. It illuminates the reasoning behind the precise instructions you receive. With this map, you are better equipped to ensure that the message you are sending to your cells arrives intact, clear, and ready to perform its designated function.

The ultimate path to wellness is built upon such foundational details, where your understanding and actions directly influence the outcome of your protocol and your journey toward renewed vitality.