Fundamentals

You may be reading this because you feel a subtle, or perhaps profound, shift in your body’s internal landscape. It could be a change in your energy, your mood, or how your body handles food. These experiences are valid and often point toward the intricate communication network of your endocrine system.

Understanding this system is the first step toward reclaiming a sense of balance and vitality. At the heart of female hormonal health lies a class of molecules known as progestogens, with natural progesterone produced by your body and its synthetic counterparts, progestins, used in medicine.

Your body is a finely tuned instrument, and introducing a synthetic hormone is like introducing a new musician into the orchestra. How that musician plays ∞ its unique properties and actions ∞ determines the harmony or discord that follows. This is particularly true when we consider metabolic health, the very process by which your body converts food into energy.

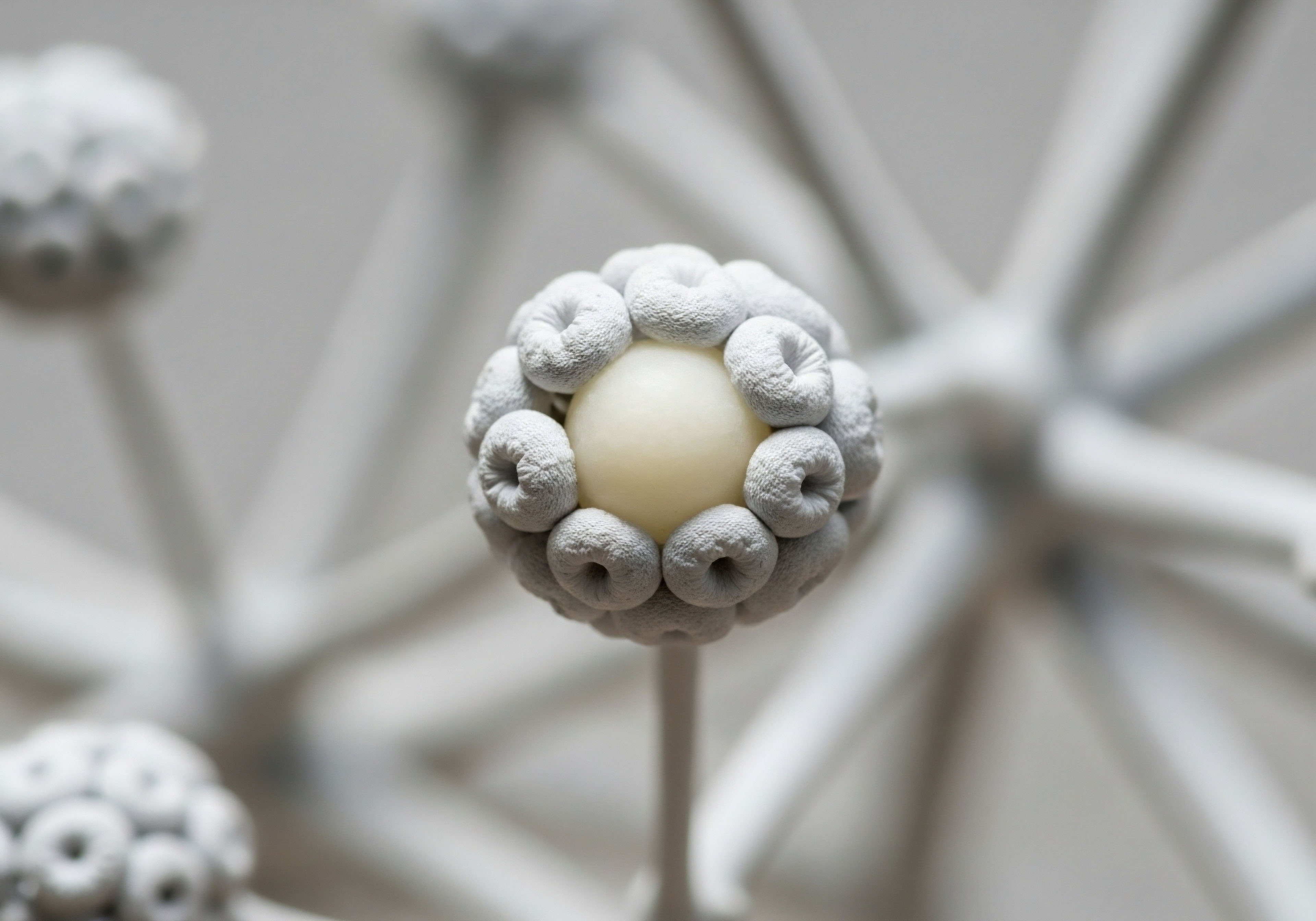

The journey to understanding how specific progestin types influence metabolic outcomes begins with a foundational concept ∞ molecular shape dictates function. Progesterone, the body’s natural progestogen, has a specific three-dimensional structure that allows it to fit perfectly into its designated receptors on cells, much like a key fits into a lock.

This interaction sends a precise signal to the cell, influencing everything from the uterine lining to brain function. Progestins, on the other hand, are molecules designed in a laboratory to mimic progesterone. While they are engineered to activate the progesterone receptor, their structures are different from natural progesterone.

These structural differences mean they can sometimes interact with other receptors in the body, including those for androgens (male hormones), glucocorticoids (stress hormones), and mineralocorticoids (hormones that regulate fluid balance). It is this cross-reactivity that is the source of their varied metabolic effects.

The unique molecular structure of each synthetic progestin determines its interaction with various hormonal receptors, leading to a distinct profile of metabolic effects.

Imagine your body’s hormonal system as a complex switchboard. Natural progesterone is designed to press only its specific button. A progestin, however, might be shaped in a way that it not only presses the progesterone button but also nudges the adjacent buttons for androgens or other hormones.

This unintended signaling can lead to a cascade of metabolic consequences. For instance, a progestin with significant androgenic activity might send signals that alter how your liver produces cholesterol, potentially lowering the protective high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. Another progestin with glucocorticoid-like properties could influence how your cells respond to insulin, a key hormone in glucose metabolism.

These are not flaws in the design of progestins; they are inherent properties of their molecular structure, and understanding them allows for a more informed and personalized approach to hormonal therapy.

The Concept of Metabolic Health

Metabolic health is a broad term that describes how well your body generates and processes energy. It is the sum of several interconnected processes, and its key indicators provide a snapshot of your internal efficiency. When we discuss the metabolic outcomes of progestin therapy, we are primarily concerned with its influence on these key areas:

- Glucose Metabolism and Insulin Sensitivity ∞ This refers to how your body manages blood sugar. After you eat, your blood glucose rises, and the pancreas releases insulin. Insulin acts like a gatekeeper, instructing cells to take up glucose from the blood for energy. Insulin sensitivity describes how responsive your cells are to insulin’s signal. High sensitivity is good; it means a small amount of insulin is effective. Low sensitivity, or insulin resistance, means your cells ignore the signal, forcing the pancreas to produce more insulin to get the job done. Over time, this can lead to chronically high insulin and glucose levels.

- Lipid Profiles ∞ This pertains to the fats circulating in your blood, including cholesterol and triglycerides. A standard lipid panel measures total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL, often called “bad” cholesterol), high-density lipoprotein (HDL, often called “good” cholesterol), and triglycerides. The balance of these lipids is important for cardiovascular health. Hormones can significantly influence the liver’s production and clearance of these fats.

- Body Composition and Weight ∞ Hormonal signals can influence where and how your body stores fat, as well as your overall body weight. Some hormonal effects are direct, while others are indirect, potentially affecting appetite or fluid retention. Changes in body composition, particularly an increase in visceral fat (fat around the organs), are closely linked to metabolic dysfunction.

Why Progestin Structure Matters

To understand the different metabolic effects, it helps to classify progestins based on their chemical origin. They are generally derived from either progesterone itself or from testosterone. This lineage gives us a clue about their potential side-effect profile.

Progestins derived from progesterone, known as pregnanes (e.g. medroxyprogesterone acetate), are structurally closer to the natural hormone. Progestins derived from testosterone are further divided into two main groups ∞ estranes (e.g. norethindrone) and gonanes (e.g. levonorgestrel, desogestrel). The gonanes are typically more potent and have been refined over generations to reduce unwanted androgenic activity.

A fourth generation has emerged, with unique properties, such as drospirenone, which is derived from a diuretic-like molecule and has anti-androgenic and anti-mineralocorticoid effects. Each of these structural families interacts with the body’s metabolic machinery in a slightly different way, creating a spectrum of effects that can be leveraged for personalized treatment.

This foundational knowledge empowers you to ask more specific questions about your health and the therapies available. It shifts the conversation from a general concern about side effects to a specific inquiry about how a particular progestin might interact with your unique biology. Your body’s response to a hormonal therapy is a direct consequence of these molecular interactions, and understanding them is the first step in a proactive and informed health journey.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the fundamentals, we can begin to dissect the specific ways different progestins exert their influence on metabolic pathways. The clinical choice of a progestin, whether for contraception or hormone replacement therapy, is guided by a desire to achieve the primary therapeutic goal while minimizing unintended metabolic disturbances.

This requires a detailed understanding of the progestin’s pharmacological profile, which is determined not just by its binding to the progesterone receptor but by its affinity for other steroid receptors. The generational classification of progestins reflects a progressive effort by pharmacologists to create molecules with greater specificity for the progesterone receptor and a more favorable metabolic footprint.

A Generational and Structural Overview of Progestins

Progestins are synthetic hormones that can be categorized based on when they were introduced to the market and their chemical structure. This classification helps predict their clinical and metabolic effects. The testosterone-derived progestins, in particular, have undergone significant evolution.

- First Generation (Estranes) ∞ This group includes norethindrone, norethindrone acetate, and ethynodiol diacetate. Being the earliest testosterone derivatives used in oral contraceptives, they possess a notable degree of androgenic activity. This residual androgenicity can manifest as metabolic changes, such as an adverse effect on lipid profiles, specifically a potential reduction in HDL cholesterol.

- Second Generation (Gonanes) ∞ This class is represented primarily by levonorgestrel and norgestrel. These progestins are more potent than their first-generation predecessors and exhibit significant androgenic activity. This androgenic quality is responsible for some of the well-documented metabolic effects of older contraceptive formulations, including negative impacts on both glucose and lipid metabolism.

- Third Generation (Gonanes) ∞ In an effort to reduce androgenic side effects, third-generation progestins like desogestrel and gestodene were developed. These molecules were engineered to have higher progestational activity with markedly reduced androgenic effects compared to the second generation. This refinement often translates to a more neutral impact on metabolic markers. Norgestimate is also part of this group and is considered to have low androgenic activity because it is metabolized to levonorgestrel, but its overall effect is less androgenic.

- Fourth Generation and Atypical Progestins ∞ This group is defined by unique properties rather than a shared chemical backbone. The most prominent member is drospirenone, which is a derivative of spironolactone. Its defining feature is its anti-mineralocorticoid and anti-androgenic activity. This profile means it can counteract the fluid retention that estrogen can cause and may be beneficial for lipid and glucose metabolism. Other progestins like dienogest also have potent anti-androgenic properties.

The evolution of progestins across generations reflects a deliberate pharmacological effort to isolate progestational effects while minimizing androgenic activity, thereby improving metabolic outcomes.

How Do Progestin Structures Affect Specific Metabolic Pathways?

The metabolic influence of a progestin is a direct result of its binding profile. A progestin that binds strongly to the androgen receptor can trigger metabolic changes similar to those caused by testosterone. A progestin that interacts with the glucocorticoid receptor might influence insulin signaling. Let’s examine these effects in more detail.

Impact on Lipid Metabolism

The liver is the primary site of cholesterol and triglyceride synthesis, and its function is highly sensitive to hormonal signals. Estrogens, like the ethinyl estradiol found in most combined oral contraceptives, generally have a favorable effect on lipids, increasing HDL and decreasing LDL cholesterol. Progestins, however, can modulate or even counteract these effects.

- Androgenic Progestins ∞ Progestins with higher androgenic activity, such as levonorgestrel, tend to oppose the beneficial lipid effects of estrogen. They can increase the activity of an enzyme called hepatic lipase, which breaks down HDL particles. The result is a decrease in HDL levels. They may also lead to an increase in LDL levels.

- Less Androgenic and Anti-Androgenic Progestins ∞ Third-generation progestins like desogestrel and gestodene have a much weaker effect on hepatic lipase, resulting in a more neutral impact on HDL levels. Fourth-generation progestins like drospirenone, with their anti-androgenic properties, are generally considered to have a favorable or neutral effect on lipid profiles, preserving the beneficial effects of estrogen.

Influence on Glucose Metabolism and Insulin Sensitivity

The relationship between progestins and insulin sensitivity is complex. Some studies suggest that certain progestins can induce a state of insulin resistance, where the body’s cells do not respond as efficiently to insulin. This forces the pancreas to work harder, increasing insulin secretion to maintain normal blood glucose levels.

For most healthy individuals, this change is subclinical and reversible. For individuals with pre-existing conditions like Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) or a predisposition to type 2 diabetes, the choice of progestin becomes more significant.

The mechanism is thought to be related to the androgenic and glucocorticoid activity of some progestins. Androgens can contribute to insulin resistance, and any progestin with residual androgenic effects could potentially worsen insulin sensitivity. Similarly, activation of the glucocorticoid receptor can interfere with insulin signaling pathways within the cell.

Progestins with lower androgenicity are generally preferred in individuals at risk for glucose intolerance. Drospirenone, due to its unique profile, has been shown in some studies to have a neutral or even slightly beneficial effect on insulin sensitivity.

Comparative Metabolic Effects of Common Progestins

To provide a clearer picture, the following table summarizes the general metabolic tendencies of several common progestins. It is important to remember that these effects are often dose-dependent and can be modified by the type and dose of the accompanying estrogen in combined hormonal formulations.

| Progestin Type | Generation | Androgenic Activity | Impact on HDL Cholesterol | Impact on Insulin Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norethindrone | First | Moderate | May decrease | Variable, potential for slight decrease |

| Levonorgestrel | Second | High | Tends to decrease | May decrease |

| Desogestrel | Third | Very Low | Neutral or slight increase | Generally neutral |

| Norgestimate | Third | Low | Generally neutral | Generally neutral |

| Drospirenone | Fourth | Anti-androgenic | Neutral or slight increase | Neutral or may improve |

| Medroxyprogesterone Acetate (MPA) | Pregnane Derivative | Low (but has glucocorticoid activity) | May decrease | May decrease, especially at higher doses |

This comparative view highlights a critical aspect of personalized medicine. For a young, healthy individual, the metabolic impact of a second-generation progestin might be negligible. For a woman with PCOS, who already struggles with insulin resistance and dyslipidemia, a fourth-generation progestin like drospirenone could be a more metabolically sound choice.

The selection process involves a careful weighing of the progestin’s potency, its side-effect profile, and the individual’s underlying metabolic health. Understanding these differences allows for a therapeutic partnership between you and your clinician, aimed at selecting a protocol that aligns with your body’s unique physiology.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of how specific progestin types influence metabolic outcomes requires a deep dive into molecular endocrinology, focusing on steroid receptor pharmacology and the intricate crosstalk between hormonal signaling pathways.

The metabolic phenotype induced by any given progestin is not a random occurrence; it is the predictable, summative result of that molecule’s binding affinities for a spectrum of nuclear receptors, including the progesterone receptor (PR), androgen receptor (AR), glucocorticoid receptor (GR), and mineralocorticoid receptor (MR). The unique “fingerprint” of a progestin’s receptor interactions dictates its ultimate physiological and metabolic impact. The clinical significance of these interactions becomes most apparent when considering long-term health trajectories, particularly concerning cardiometabolic risk.

Steroid Receptor Promiscuity and Its Metabolic Consequences

The concept of receptor promiscuity is central to understanding progestin effects. While engineered to target the PR, many synthetic progestins retain structural similarities to other endogenous steroids, allowing them to bind to and activate or block other receptors. This off-target activity is the primary driver of their diverse metabolic profiles.

- Androgen Receptor (AR) Agonism ∞ Progestins derived from 19-nortestosterone (the estranes and gonanes) often possess residual AR agonistic activity. When a progestin like levonorgestrel binds to and activates the AR in hepatocytes, it can upregulate the expression of hepatic lipase. This enzyme is critical in the reverse cholesterol transport pathway, facilitating the catabolism of HDL2 particles into smaller HDL3 particles and their subsequent clearance. This mechanism directly explains the observed decrease in HDL cholesterol associated with highly androgenic progestins. Furthermore, AR activation in adipose tissue and muscle can contribute to insulin resistance by interfering with intracellular insulin signaling cascades, such as the PI3K/Akt pathway.

- Glucocorticoid Receptor (GR) Agonism ∞ Some progestins, most notably medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), exhibit significant binding affinity for the GR. Glucocorticoids are known to be potent modulators of glucose metabolism. Activation of the GR can promote gluconeogenesis in the liver and induce insulin resistance in peripheral tissues. The GR-mediated effects of MPA may explain, in part, the negative metabolic outcomes observed in some studies, particularly with the high-dose depot injection used for contraception. This interaction represents a distinct pathway to metabolic dysfunction separate from androgenicity.

- Mineralocorticoid Receptor (MR) Antagonism ∞ Drospirenone is unique among progestins due to its structural relation to spironolactone, an MR antagonist. By blocking the MR, drospirenone inhibits the action of aldosterone. Aldosterone promotes sodium and water retention, which can increase blood pressure. Drospirenone’s anti-mineralocorticoid activity leads to a mild diuretic effect. From a metabolic standpoint, this is significant because the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) is increasingly implicated in metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance. By opposing aldosterone, drospirenone may offer a more favorable cardiometabolic profile, a hypothesis supported by its neutral-to-positive effects on blood pressure and insulin sensitivity markers in many clinical trials.

What Are the Implications for Endothelial Function?

The health of the vascular endothelium, the single-cell layer lining all blood vessels, is a critical determinant of cardiovascular health. Endothelial dysfunction is an early event in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Estrogens are generally protective of the endothelium, promoting the production of the vasodilator nitric oxide (NO).

The type of co-administered progestin can significantly modulate this effect. Progestins with androgenic properties may counteract the beneficial vascular effects of estrogen. In contrast, newer progestins with neutral or anti-androgenic properties appear to preserve estrogen’s positive influence on endothelial function. Drospirenone, for instance, has been shown in some vascular studies to have a neutral effect on flow-mediated dilation, a key measure of endothelial health, suggesting it does not interfere with the vasoprotective actions of estrogen.

The specific binding affinity of a progestin for androgen, glucocorticoid, and mineralocorticoid receptors is the primary determinant of its influence on lipid metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and vascular health.

A Deeper Look at Progestin Receptor Binding Profiles

The following table provides a more granular view of the relative binding affinities (RBAs) of various progestins for the different steroid receptors. The RBA is typically measured in vitro and compared to the natural ligand for that receptor (e.g. progesterone for PR, testosterone for AR). A higher RBA indicates stronger binding. This data provides a molecular basis for the clinical observations discussed.

| Compound | Progesterone Receptor (PR) | Androgen Receptor (AR) | Glucocorticoid Receptor (GR) | Mineralocorticoid Receptor (MR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progesterone (Natural) | 100% | Low (Antagonistic) | Low | Moderate (Antagonistic) |

| Levonorgestrel | High | High | Low | Negligible |

| Norethindrone | Moderate | Moderate | Negligible | Negligible |

| Desogestrel (active metabolite ∞ etonogestrel) | Very High | Low | Low | Negligible |

| Drospirenone | High | Moderate (Antagonistic) | Negligible | High (Antagonistic) |

| Medroxyprogesterone Acetate (MPA) | High | Low | Moderate | Negligible |

| Dienogest | High | Moderate (Antagonistic) | Negligible | Negligible |

How Does This Translate to Clinical Decision Making?

This academic understanding has profound clinical implications, especially in the context of long-term hormonal therapy for women with underlying metabolic vulnerabilities. For a patient with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), characterized by hyperandrogenism and insulin resistance, prescribing a combined oral contraceptive containing a progestin with high androgenic activity like levonorgestrel could potentially exacerbate her metabolic condition.

A formulation containing an anti-androgenic progestin like drospirenone or dienogest would be a more physiologically sound choice, as it would not only provide contraception but also help to mitigate her underlying hyperandrogenism. Similarly, for a perimenopausal woman seeking hormone therapy who has risk factors for cardiovascular disease, the choice of progestin is critical.

The use of natural micronized progesterone or a progestin with a more favorable metabolic profile like drospirenone is often preferred over more androgenic options or MPA, due to the latter’s potential negative impact on lipids and glucose metabolism.

The goal is to tailor the hormonal intervention to the individual’s specific physiology and risk profile, a practice that is the essence of modern, personalized endocrinology. The conversation moves from simply managing symptoms to optimizing long-term metabolic health and minimizing iatrogenic risk.

References

- Sitruk-Ware, R. & Nath, A. (2013). Characteristics and metabolic effects of estrogen and progestins contained in oral contraceptive pills. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 27(1), 13 ∞ 24.

- Justice, N. A. & Le, J. K. (2024). Progestins. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- Wiegratz, I. & Kuhl, H. (2006). Metabolic and clinical effects of progestogens. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care, 11(3), 153 ∞ 161.

- Stanczyk, F. Z. (2003). All progestins are not created equal. Steroids, 68(10-13), 879-890.

- Apgar, B. S. & Greenberg, G. (2000). Using progestins in clinical practice. American Family Physician, 62(8), 1839-1846.

Reflection

You have just navigated a deep exploration of the biochemical and physiological landscape of progestins. This knowledge is more than a collection of scientific facts; it is a toolkit for understanding your own body with greater clarity and precision.

The way you feel each day ∞ your energy, your clarity of mind, your physical well-being ∞ is the result of a constant, silent conversation between billions of cells, orchestrated by these powerful hormonal messengers. Recognizing that different progestins speak a different molecular language allows you to become a more active participant in that conversation.

This information serves as a map, but you are the expert on the territory of your own body. The symptoms you experience and the health goals you hold are the starting point for any therapeutic path. The science presented here is meant to bridge the gap between your lived experience and the clinical decisions you and your healthcare provider make together.

It provides a framework for asking deeper, more specific questions and for appreciating the profound connection between a single molecule and your overall metabolic vitality. Your health journey is uniquely yours, and arming yourself with this level of understanding is a powerful act of self-advocacy and a foundational step toward achieving a state of optimal function and well-being.