Fundamentals

You may be reading this because you feel a persistent sense of fatigue that sleep does not seem to fix. Perhaps you experience a mental fog that makes clear thought difficult, or you are contending with unexplained changes in your weight and mood.

These experiences are common for individuals with thyroid-related concerns, and they represent a disruption within a complex biological system. Your body is not a collection of independent parts; it is a highly interconnected network. The sensations you are experiencing are valid signals from this network, and understanding their origin is the first step toward restoring your vitality.

The thyroid gland, a small butterfly-shaped organ at the base of your neck, is a central regulator of your body’s metabolic rate, influencing everything from energy levels to body temperature. Yet, it does not operate in isolation.

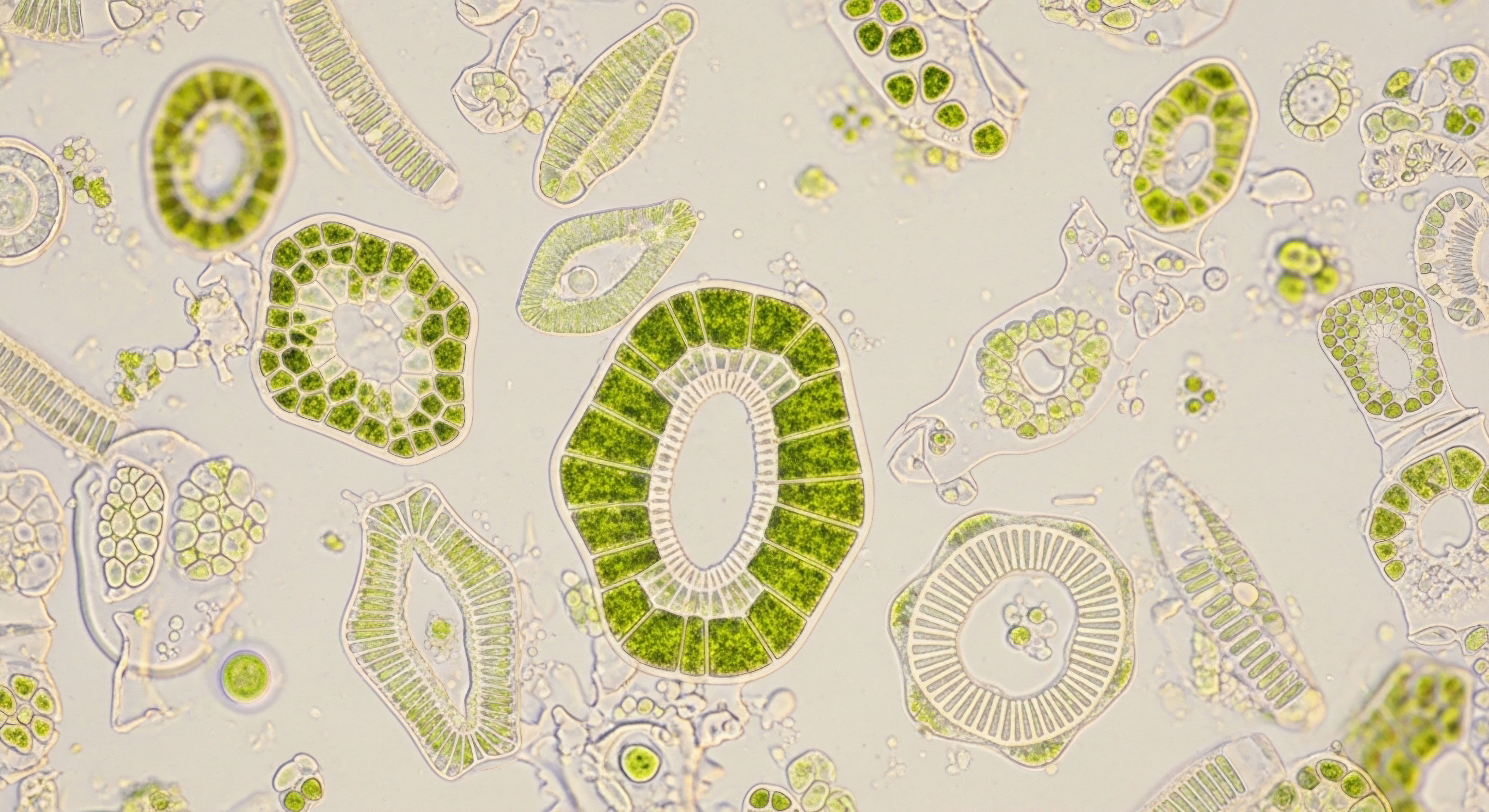

A significant and often overlooked partner in thyroid function is the vast, dynamic ecosystem residing within your intestines ∞ the gut microbiome. This internal world, composed of trillions of microorganisms, acts as a critical support system for your thyroid. Think of the thyroid as a central command center and the gut as its essential logistics and communications department.

This department is responsible for processing raw materials, activating key messages, and maintaining a secure perimeter. When this department is in disarray, command’s ability to manage the entire system is compromised, regardless of how well the command center itself is built. Therefore, addressing your thyroid health requires looking beyond the neck and into the intricate workings of your digestive tract.

The gut microbiome acts as a crucial regulatory hub that directly and indirectly manages the resources and signals necessary for optimal thyroid function.

The Thyroid’s Basic Operations

To appreciate the gut’s role, we must first understand the thyroid’s primary output. The gland produces several hormones, but the two most important are thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). T4 is the primary hormone produced, a stable, long-lasting molecule that circulates throughout the body.

You can consider T4 a prohormone, a precursor molecule that is largely inactive. For your body to use it to generate energy, regulate your heartbeat, or maintain cognitive function, T4 must be converted into the much more potent, active form, T3. This conversion is a critical step in the process. Your body’s cells have receptors for T3, which, when activated, switch on metabolic processes.

The entire system is regulated by a feedback loop involving the brain. The pituitary gland in your brain releases Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH). When the brain senses that thyroid hormone levels are low, it releases more TSH to tell the thyroid gland to produce more T4.

Conversely, when levels are sufficient, TSH production decreases. This is why physicians frequently test TSH levels; it serves as a sensor for the brain’s perception of the body’s thyroid status. A high TSH often suggests the thyroid is underactive (hypothyroidism), as the brain is “shouting” for more hormone production.

However, the TSH level alone does not tell the full story. It does not reveal how effectively your body is converting the inactive T4 into the biologically active T3, a process in which your gut is a key participant.

Where Does the Gut Microbiome Fit In?

The connection between your gut and thyroid is not theoretical; it is a biochemical reality. A substantial portion of T4 to T3 conversion, estimated to be around 20%, occurs not in the thyroid gland itself, but in peripheral tissues, with the gut being a primary location.

Specific bacteria within your intestines produce an enzyme called intestinal sulfatase. This enzyme effectively performs the final step of activation, cleaving a sulfate molecule from thyroid hormone precursors to release active T3 into circulation. If the composition of your gut microbiome is imbalanced ∞ a state known as dysbiosis ∞ this critical conversion process can be impaired.

You could have sufficient T4, and a normal TSH, yet still experience the symptoms of low thyroid function because you are not producing enough active T3 to run your cells efficiently.

This is just one of the gut’s foundational roles. The microbiome also governs the absorption of key nutrients essential for thyroid health and helps to maintain the integrity of the intestinal barrier, which is paramount for preventing the kind of immune system disruptions that underlie autoimmune thyroid conditions. Understanding this relationship shifts the focus from merely supplementing a hormone to restoring the biological environment that allows your own body to produce, convert, and utilize it correctly.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational understanding of the gut-thyroid connection, we can examine the precise mechanisms through which specific microbial populations influence thyroid physiology. The relationship is not passive; it is an active, ongoing biochemical dialogue. Probiotic strains, which are specific, well-defined beneficial microorganisms, can be seen as targeted interventions designed to improve the quality of this dialogue.

Their influence can be categorized into three primary areas of support ∞ enhancing the nutrient supply chain, optimizing hormone activation, and modulating immune system communication. Addressing these areas provides a more robust and systemic approach to thyroid wellness than focusing on a single lab value might suggest.

How Do Probiotics Support the Thyroid Nutrient Supply Chain?

The thyroid gland cannot produce its hormones from thin air. It requires a steady supply of specific micronutrients, the availability of which is directly influenced by the health of your gut. An imbalanced microbiome or poor digestive function can lead to malabsorption, meaning that even a nutrient-rich diet may not translate into adequate resources for your thyroid. Probiotics can help restore the gut’s ability to extract and process these vital elements.

Consider the following key nutrients and their dependence on gut function:

| Nutrient | Role in Thyroid Function | Connection to Gut Health and Probiotics |

|---|---|---|

| Iodine | The fundamental building block of T4 and T3 hormones. Each molecule of T4 contains four iodine atoms, and T3 contains three. | The gut microbiome helps regulate iodine uptake and metabolism. Certain bacteria can bind iodine, affecting its availability. A healthy gut environment ensures more stable and efficient absorption. |

| Selenium | A critical cofactor for the deiodinase enzymes that convert inactive T4 to active T3. It also has potent antioxidant properties that protect the thyroid gland from oxidative stress generated during hormone synthesis. | Probiotic strains, particularly of the Lactobacillus family, have been shown to convert dietary selenium into more bioavailable forms like selenocysteine and selenomethionine, which the body can use more effectively. |

| Zinc | Plays a role in both the synthesis of thyroid hormones and the function of the deiodinase enzymes. Zinc deficiency can impair T4 to T3 conversion. | Chronic gut inflammation can impair zinc absorption. By reducing inflammation and improving the health of the intestinal lining, probiotics can enhance the body’s ability to absorb zinc from the diet. |

| Iron | The enzyme thyroid peroxidase (TPO), which is essential for producing thyroid hormones, is iron-dependent. Iron deficiency is strongly associated with hypothyroidism. | Gut conditions like celiac disease or low stomach acid can severely limit iron absorption. Probiotics that help balance the gut environment can improve conditions for iron uptake. |

Optimizing Hormone Activation and Metabolism

As established, the gut is a major site for the conversion of T4 to T3. This process is mediated by bacterial enzymes. An imbalance in the gut microbiome, with an overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria and a reduction in beneficial species, can directly suppress this conversion.

The result is a metabolic bottleneck ∞ the thyroid produces the precursor hormone, but the body fails to activate it efficiently. This leads to a state where TSH and T4 levels might appear normal, while T3 levels are suboptimal, leaving the individual with persistent hypothyroid symptoms.

The gut’s enzymatic activity is a key determinant of how much active T3 hormone is available to your body’s cells.

Furthermore, the gut microbiota influences the enterohepatic circulation of thyroid hormones. Hormones are conjugated in the liver, excreted into the gut via bile, and can then be deconjugated by bacterial enzymes and reabsorbed. A healthy microbiome facilitates this recycling process, helping to maintain a stable pool of circulating thyroid hormones.

Dysbiosis disrupts this cycle, leading to increased excretion and loss of thyroid hormones in the stool. Specific probiotic strains can help restore the microbial balance needed for both efficient T4-to-T3 conversion and proper hormone recycling.

Modulating Immune System Communication

The vast majority of cases of hypothyroidism in the developed world are autoimmune in nature, primarily Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. In this condition, the immune system mistakenly identifies thyroid tissue as a foreign invader and attacks it. Since approximately 70-80% of the body’s immune cells reside in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), the health of the intestinal barrier is paramount for maintaining immune tolerance.

A compromised gut barrier, often called “leaky gut” or increased intestinal permeability, allows undigested food particles and bacterial components to pass into the bloodstream. One of the most inflammatory of these components is lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a toxin from the cell wall of gram-negative bacteria. When LPS enters the circulation, it triggers a strong systemic immune response. This chronic, low-grade inflammation can be a primary driver of autoimmunity. Probiotics contribute to thyroid health by:

- Strengthening the Gut Barrier ∞ Certain strains, like Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Bifidobacterium longum, enhance the production of tight junction proteins, which are the molecules that “glue” intestinal cells together, reducing permeability.

- Displacing Pathogens ∞ Probiotics compete with pathogenic bacteria for resources and attachment sites on the intestinal wall, making it harder for harmful microbes to flourish.

- Regulating Immune Signals ∞ Beneficial bacteria interact with immune cells in the GALT, promoting the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines and encouraging the development of regulatory T-cells (T-regs), which help to suppress autoimmune reactions.

By restoring the integrity of the gut barrier and calming immune overactivity at its source, probiotics can help address the underlying drivers of autoimmune thyroid disease, rather than just managing its symptoms.

Academic

A sophisticated examination of the gut-thyroid axis requires a deep analysis of the molecular mechanisms that initiate and perpetuate autoimmune thyroid disease (AITD), particularly Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. The central thesis is that intestinal dysbiosis, specifically an increase in gram-negative bacteria, leads to elevated translocation of the endotoxin lipopolysaccharide (LPS) across a compromised epithelial barrier.

This event serves as a potent trigger for a cascade of innate and adaptive immune responses that ultimately culminate in the loss of self-tolerance to thyroid antigens. Understanding this pathway provides a clear rationale for therapeutic interventions aimed at restoring gut barrier function and modulating the microbiome.

The Pathophysiology of LPS Translocation and Immune Activation

LPS is a major component of the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria. In a state of eubiosis (a healthy gut balance), its presence is managed locally. However, in dysbiosis, the death of these bacteria releases large quantities of LPS into the gut lumen.

Concurrently, dysbiosis is associated with a downregulation of tight junction proteins like occludin and zonulin-1, leading to increased intestinal permeability. This allows LPS to translocate from the gut lumen into the systemic circulation, a condition known as metabolic endotoxemia.

Once in the bloodstream, LPS acts as a powerful pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP). It is primarily recognized by Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), a receptor expressed on various innate immune cells, including macrophages and dendritic cells.

The binding of LPS to TLR4 initiates a downstream signaling cascade, predominantly through the MyD88-dependent pathway, which culminates in the activation of the transcription factor Nuclear Factor-kappa B (NF-κB).

NF-κB activation drives the transcription of a wide array of pro-inflammatory genes, leading to the systemic release of cytokines such as Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α), Interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and Interleukin-6 (IL-6). This creates a state of chronic, low-grade systemic inflammation that is a hallmark of many autoimmune conditions.

How Does Systemic Inflammation from LPS Target the Thyroid?

The link between LPS-induced systemic inflammation and a specific attack on the thyroid gland can be explained by several interconnected mechanisms. First, the inflammatory environment itself can cause collateral damage to the thyroid.

Thyrocytes, the cells that make up the thyroid follicles, can be induced by cytokines like TNF-α to express molecules that they normally would not, making them appear “foreign” to the immune system. Second, and more specifically, is the concept of molecular mimicry.

It is hypothesized that structural similarities exist between components of certain bacteria and thyroid proteins, such as thyroglobulin (Tg) or thyroid peroxidase (TPO). When the immune system mounts a vigorous response against a bacterial antigen (or LPS), the activated T-cells and B-cells may cross-react with these structurally similar thyroid proteins, initiating an autoimmune attack.

The immune system, primed by gut-derived endotoxins, may lose its ability to distinguish between a foreign threat and the body’s own thyroid tissue.

Research has demonstrated that LPS can have even more direct effects. Studies have shown that LPS can directly interact with thyrocytes, which also express TLR4. This interaction can trigger the production of chemokines ∞ powerful signaling molecules that attract immune cells ∞ directly within the thyroid gland itself.

This creates a self-perpetuating cycle ∞ LPS triggers systemic inflammation, which attracts immune cells to the thyroid, and LPS can also directly stimulate the thyroid to call for more immune cells, facilitating lymphocytic infiltration and progressive tissue destruction.

| LPS-Mediated Effect | Biochemical Mechanism | Physiological Consequence for the Thyroid |

|---|---|---|

| Suppression of the HPT Axis | LPS-induced inflammation in the hypothalamus can inhibit the release of Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone (TRH), subsequently reducing TSH secretion from the pituitary. | Reduced central stimulation of the thyroid gland, contributing to a state of non-thyroidal illness syndrome or “euthyroid sick syndrome.” |

| Induction of Autoimmunity | Activation of TLR4 on antigen-presenting cells, leading to a Th1-dominant immune response and potential cross-reactivity with thyroid antigens (molecular mimicry). | Generation of autoantibodies (TPOAb, TgAb) and autoreactive T-cells that attack and destroy thyroid tissue, characteristic of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. |

| Direct Thyrocyte Activation | LPS binds to TLR4 expressed on thyroid follicular cells, stimulating the local production of inflammatory chemokines (e.g. RANTES, MCP-1). | Active recruitment of lymphocytes into the thyroid gland, accelerating the inflammatory process and follicular cell death. |

| Impaired T4-to-T3 Conversion | Systemic inflammation from LPS can inhibit the activity of the type 1 deiodinase (D1) enzyme in peripheral tissues like the liver. | Reduced conversion of inactive T4 to active T3, leading to symptoms of hypothyroidism even with adequate T4 levels. |

What Is the Therapeutic Rationale for Probiotic Intervention?

Given this detailed pathogenic model, the therapeutic goal becomes clear ∞ reduce the translocation of LPS from the gut into the circulation. This is where specific probiotic strains offer a targeted biological intervention. Their mechanisms of action directly counter the initial steps of the disease process.

- Enhancement of Barrier Integrity ∞ Probiotic species such as Lactobacillus plantarum and Bifidobacterium infantis have been shown in clinical studies to increase the expression of genes coding for tight junction proteins. By physically strengthening the intestinal barrier, they reduce the paracellular flux of LPS.

- Competitive Exclusion and Microbiome Modulation ∞ Probiotics compete with gram-negative bacteria for nutrients and adhesion sites. Some strains also produce bacteriocins, which are antimicrobial peptides that can directly inhibit the growth of pathogenic species, thereby reducing the overall LPS load in the gut lumen.

- Immunomodulation at the Source ∞ Certain probiotic strains can modulate the immune response within the gut. They can steer the immune system away from a pro-inflammatory Th1/Th17 phenotype, which is implicated in autoimmunity, towards a more tolerant state characterized by the activity of regulatory T-cells and the production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. This helps to quell the initial immune overreaction to gut-derived antigens.

By focusing on the gut barrier and the microbial ecosystem it contains, this approach seeks to extinguish the inflammatory fire at its source, rather than simply managing the downstream consequences of a system-wide conflagration. It represents a shift toward addressing the root immunological and metabolic disturbances that drive autoimmune thyroid disease.

References

- Knezevic, J. Starchl, C. Tmava Berisha, A. & Amrein, K. “Thyroid-Gut-Axis ∞ How Does the Microbiota Influence Thyroid Function?” Nutrients, vol. 12, no. 6, 2020, p. 1769.

- Fröhlich, E. & Wahl, R. “Microbiota and Thyroid Interaction in Health and Disease.” Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 30, no. 8, 2019, pp. 479-490.

- Virili, C. & Centanni, M. “Does microbiota composition affect thyroid homeostasis?” Endocrine, vol. 49, no. 3, 2015, pp. 583-587.

- Shu, Qinxi, et al. “Effect of probiotics or prebiotics on thyroid function ∞ A meta-analysis of eight randomized controlled trials.” PLoS One, vol. 19, no. 1, 2024, e0296733.

- Ishaq, H. M. et al. “The role of gut microbiota in the pathology of autoimmune diseases.” Journal of Immunology Research, vol. 2017, 2017, 5409297.

- Cayres, L. C. F. de Salis, L. V. V. & Rodrigues, G. “Detection of antibodies against gut bacteria in patients with autoimmune thyroid diseases.” Endocrine, vol. 52, no. 3, 2016, pp. 543-551.

- Mori, K. Nakagawa, Y. & Ozaki, H. “Does the gut microbiota trigger Hashimoto’s thyroiditis?” Discovery Medicine, vol. 14, no. 78, 2012, pp. 321-326.

- Eskes, D. & Wiersinga, W. M. “The role of the gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of Graves’ disease.” European Thyroid Journal, vol. 8, no. 5, 2019, pp. 227-235.

- Carpi, S. et al. “Bacterial lipopolysaccharide stimulates the thyrotropin-dependent thyroglobulin gene expression at the transcriptional level by involving the transcription factors thyroid transcription factor-1 and paired box domain transcription factor 8.” Endocrinology, vol. 148, no. 11, 2007, pp. 5473-5483.

Reflection

Considering Your Body as a System

The information presented here moves the conversation about thyroid health from a narrow focus on a single gland to a broader appreciation of an interconnected system. Your body’s functions are not siloed. The energy you feel, the clarity of your thoughts, and the stability of your immune system are all outcomes of a complex network of communication.

The dialogue between your gut microbiome and your endocrine system is a foundational part of this network. Recognizing this connection allows you to see your symptoms not as isolated failures, but as signals from a system requesting support.

This perspective invites you to think about your health in a different way. It suggests that true, sustainable wellness comes from restoring the function of the entire system, not just patching over a single endpoint. The journey to understanding your own biology is a personal one.

The knowledge you have gained is a tool, a map that can help you ask more informed questions and make more deliberate choices. Your path forward is unique to your biology, your history, and your goals. The next step is to consider how you can best support the intricate, intelligent system that is your body.