Fundamentals

The experience of menopausal transition Meaning ∞ The Menopausal Transition, frequently termed perimenopause, represents the physiological phase preceding menopause, characterized by fluctuating ovarian hormone production, primarily estrogen and progesterone, culminating in the eventual cessation of menstruation. is written in the language of your body’s internal communication network. The sensations of heat that rise unexpectedly, the shifts in mood that feel untethered to your daily life, the alterations in your sleep patterns and energy reserves ∞ these are the direct results of a recalibration within your endocrine system.

At the heart of this recalibration is a change in the production of key hormones, most centrally estrogen. Your lifelong biological rhythm is entering a new phase. Understanding how to support your body through this transition begins with the most fundamental inputs you provide it every day ∞ the food you consume.

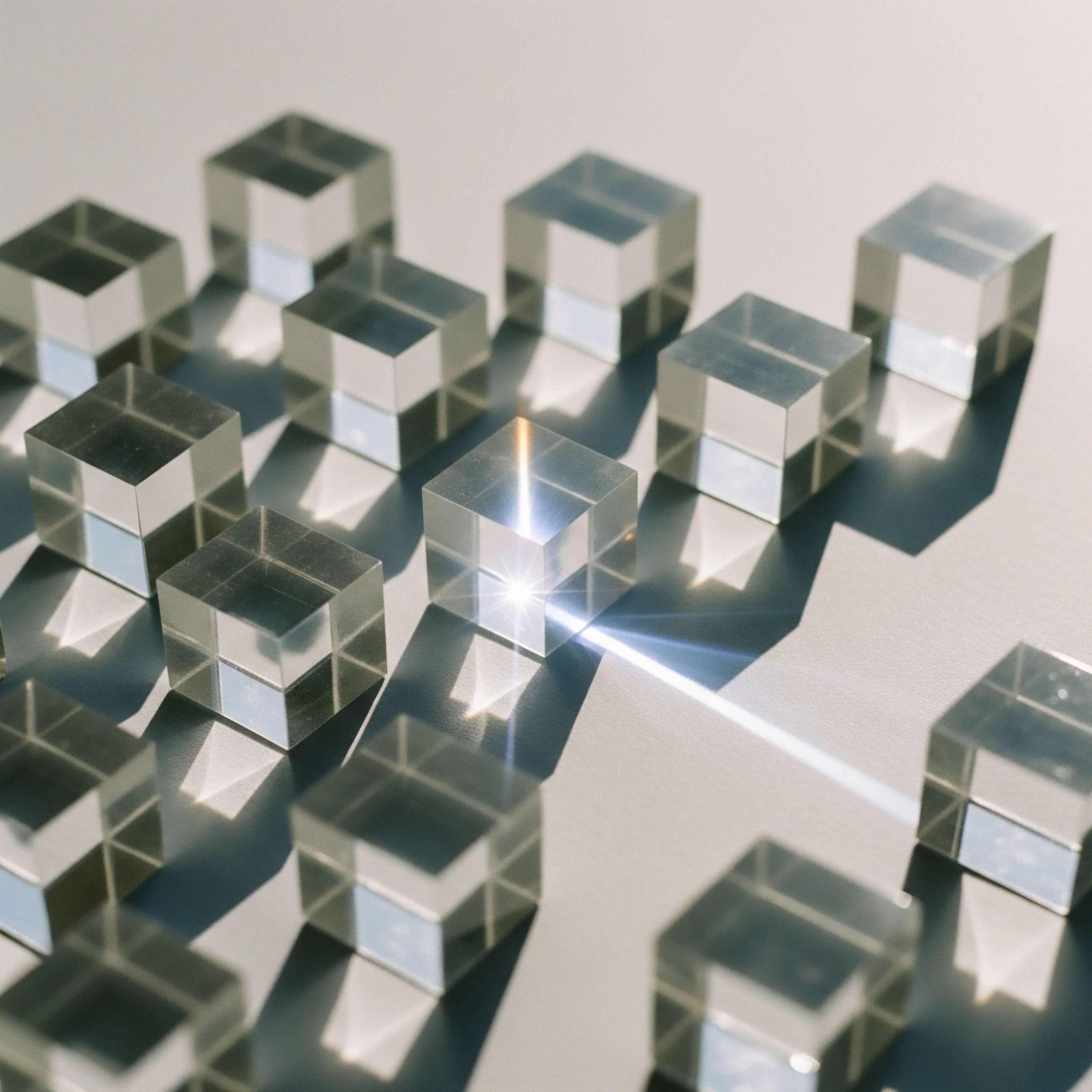

Specifically, the three macronutrients ∞ protein, carbohydrates, and fats ∞ are the primary architectural and fuel components that your body uses to navigate this new hormonal landscape. They are the raw materials for your physiological resilience.

Each macronutrient holds a unique and powerful influence over the way your hormonal systems function, especially during the dynamic changes of menopause. Think of your endocrine system as a finely tuned orchestra; for decades, estrogen acted as a primary conductor, guiding the tempo and performance of numerous bodily processes.

As estrogen’s role diminishes, other conductors, such as insulin, must take on a more prominent role, and the entire symphony must learn a new score. The composition of your meals directly influences these other conductors, determining whether the resulting music is chaotic or coherent.

By consciously selecting the quality and quantity of your macronutrients, you are actively participating in the process of creating a new, stable biological rhythm. This is the foundational principle of reclaiming your vitality. You are learning to nourish your body for the specific biological reality it now inhabits.

The Foundational Role of Protein

Protein serves as the primary structural component for nearly every part of your body, from muscle fibers to enzymes that facilitate countless chemical reactions. During the menopausal transition, its importance becomes even more pronounced. The decline in estrogen signaling directly accelerates the loss of lean muscle Meaning ∞ Lean muscle refers to skeletal muscle tissue that is metabolically active and contains minimal adipose or fat content. mass, a condition known as sarcopenia.

This loss of muscle is a critical issue because muscle tissue is a primary site of metabolic activity. It is a glucose-consuming organ, and its reduction means your body has less capacity to manage blood sugar Meaning ∞ Blood sugar, clinically termed glucose, represents the primary monosaccharide circulating in the bloodstream, serving as the body’s fundamental and immediate source of energy for cellular function. effectively. This can lead to increased fat storage, particularly around the abdomen, and a higher risk of insulin resistance.

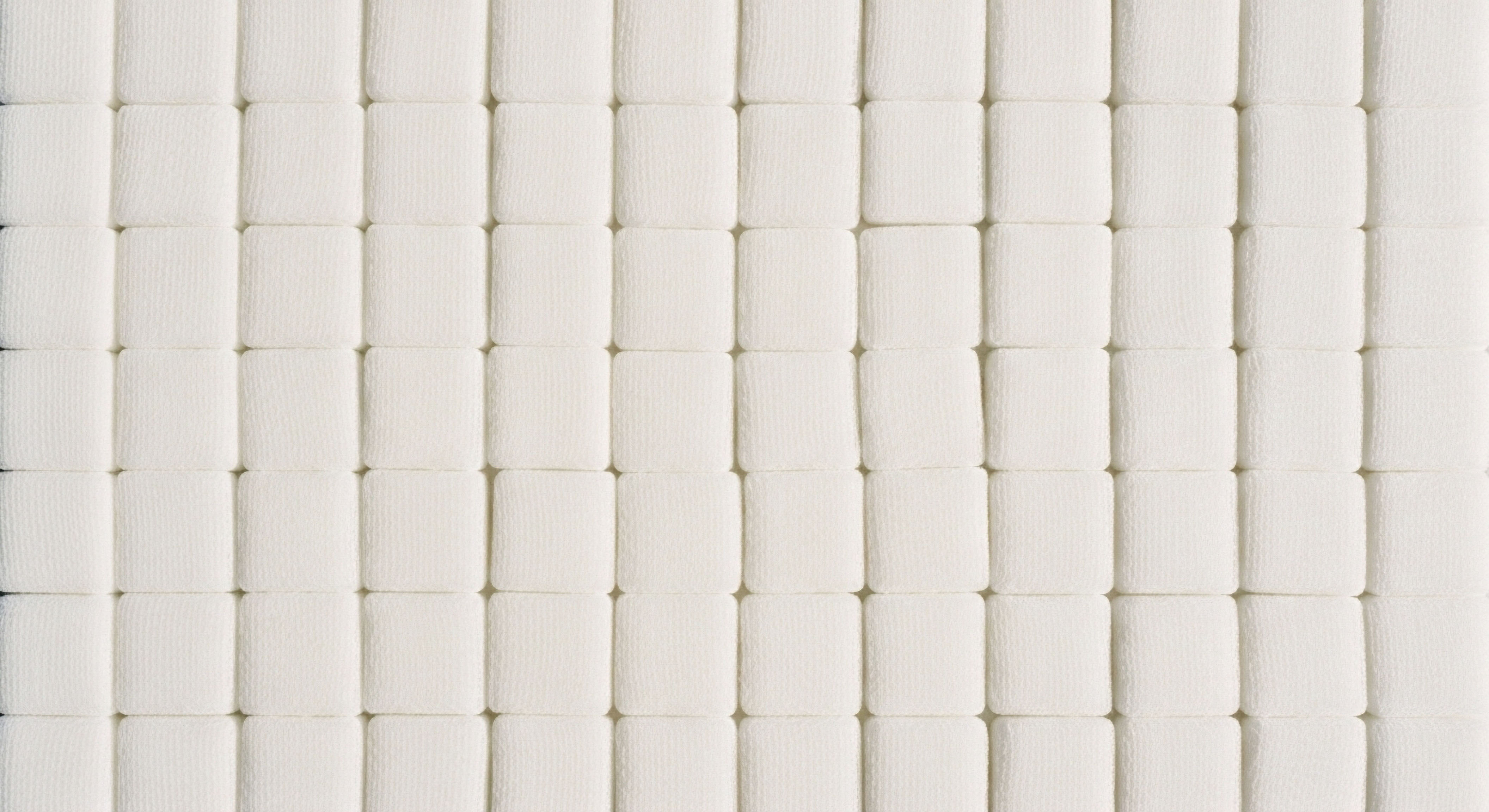

A consistent and adequate intake of high-quality protein provides the essential amino acids Amino acids can support testosterone’s anabolic signaling by influencing hormone synthesis and enhancing cellular receptor sensitivity. your body requires to counteract this process. It is the biological resource needed to preserve metabolically active muscle tissue.

Consuming sufficient protein at each meal sends a clear signal to your body to preserve and, where possible, build muscle. This has a cascading effect on your overall metabolic health. Preserving muscle mass Meaning ∞ Muscle mass refers to the total quantity of contractile tissue, primarily skeletal muscle, within the human body. helps maintain your resting metabolic rate, which is the number of calories your body burns at rest.

A higher metabolic rate Meaning ∞ Metabolic rate quantifies the total energy expended by an organism over a specific timeframe, representing the aggregate of all biochemical reactions vital for sustaining life. makes weight management more achievable. Moreover, protein has a higher thermic effect of food compared to carbohydrates and fats, meaning your body expends more energy digesting and processing it. This contributes to a healthier energy balance. Adequate protein intake also supports bone density, which is another system vulnerable to the decline in estrogen.

The amino acids Meaning ∞ Amino acids are fundamental organic compounds, essential building blocks for all proteins, critical macromolecules for cellular function. from dietary protein are integral to the collagen matrix that forms the structure of your bones. In this way, protein provides the literal framework for a strong and resilient body during and after menopause.

Carbohydrates as Information and Energy

Carbohydrates are your body’s principal source of energy, but their role extends far beyond simple fuel. The type of carbohydrate you consume transmits critical information to your hormonal systems, particularly to insulin, the hormone responsible for managing blood sugar.

The menopausal transition often brings with it a state of increased insulin resistance, where your cells become less responsive to insulin’s signals. This means your pancreas must produce more insulin to manage the same amount of glucose, a state which promotes fat storage and inflammation.

Complex carbohydrates, found in whole grains, legumes, and vegetables, are digested slowly due to their high fiber content. This slow digestion leads to a gradual release of glucose into the bloodstream, placing less stress on your insulin response system. This measured release of energy helps maintain stable blood sugar Peptide therapies can alter fluid dynamics by influencing kidney function, a process managed with dietary electrolyte support. levels throughout the day, which in turn contributes to more stable moods and consistent energy.

Conversely, simple or refined carbohydrates, such as those in sugary drinks, white bread, and processed snacks, are rapidly digested. They cause a sharp spike in blood glucose, demanding a large and rapid insulin surge. This can lead to a subsequent crash in blood sugar, contributing to feelings of fatigue, irritability, and cravings for more sugar.

This volatility is particularly taxing during menopause, when the nervous system is already more sensitive due to fluctuating estrogen levels. Fiber, an indigestible carbohydrate, plays another vital role. It supports a healthy gut microbiome, which is essential for proper hormone metabolism.

A specific community of gut bacteria, known as the estrobolome, is responsible for processing and eliminating excess estrogens from the body. A high-fiber diet nourishes these beneficial bacteria, supporting a healthier hormonal balance and reducing the burden on your system.

A consistent intake of high-quality protein provides the essential amino acids your body requires to counteract the accelerated loss of lean muscle mass associated with menopause.

The Critical Function of Dietary Fats

Dietary fats have long been misunderstood, yet they are absolutely essential for hormonal health, especially during menopause. Fats are the structural building blocks for all steroid hormones, including estrogen and progesterone. Without an adequate supply of healthy fats, your body lacks the fundamental raw materials needed for hormone production, even at the new, lower levels characteristic of menopause.

Healthy fats, such as monounsaturated fats found in avocados, olive oil, and nuts, and polyunsaturated fats, particularly omega-3 fatty acids Meaning ∞ Omega-3 fatty acids are essential polyunsaturated fatty acids with a double bond three carbons from the methyl end. found in fatty fish, flaxseeds, and chia seeds, are critical for cellular health. They form the lipid bilayer of every cell membrane in your body, ensuring that cells remain fluid and responsive to hormonal signals. A healthy cell membrane allows hormones to dock with their receptors effectively, ensuring that their messages are received and acted upon.

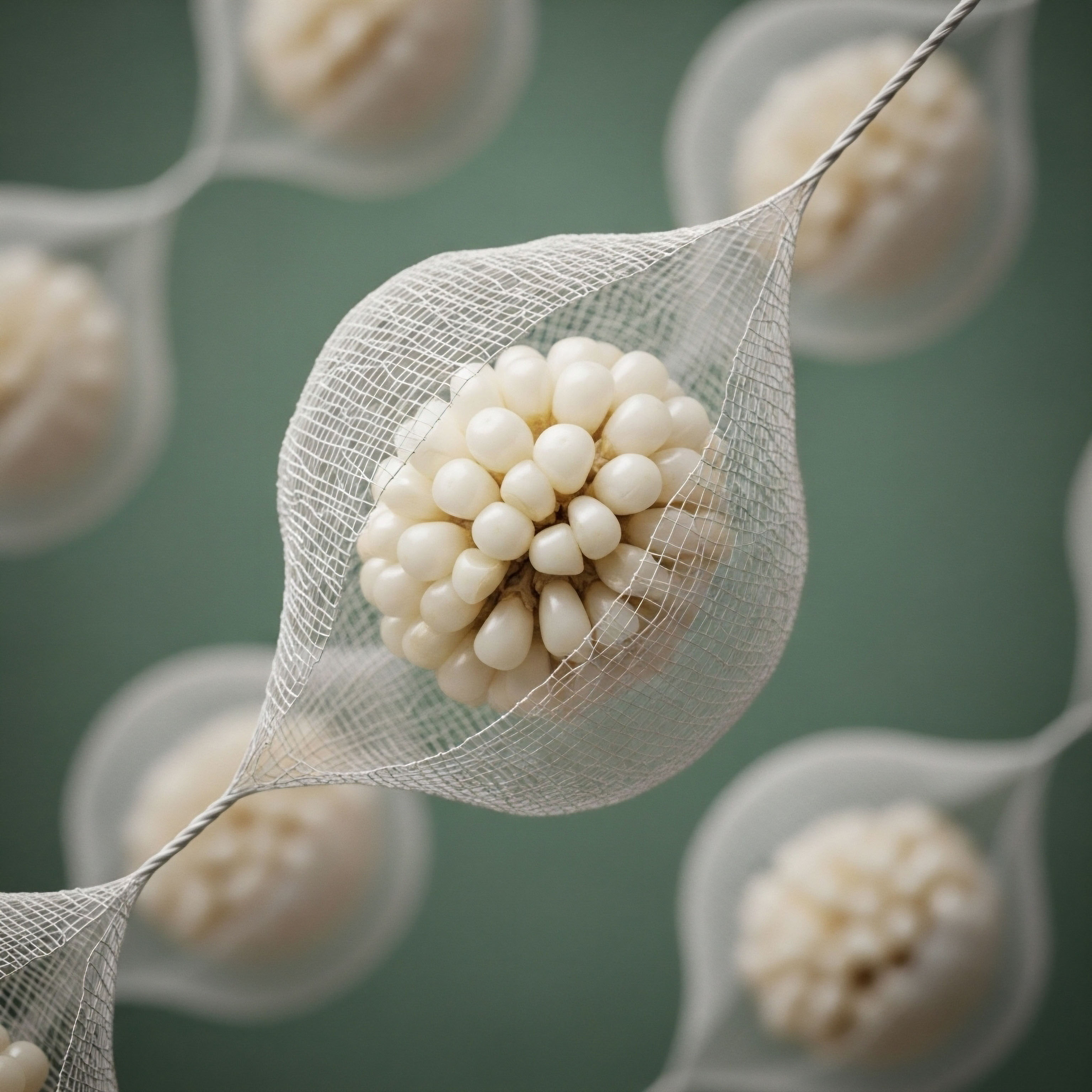

Furthermore, fats play a central role in managing inflammation. The menopausal transition is often associated with an increase in systemic inflammation, which can contribute to a wide range of symptoms, including joint pain, cognitive fog, and an increased risk of chronic disease. Omega-3 fatty acids Meaning ∞ Fatty acids are fundamental organic molecules with a hydrocarbon chain and a terminal carboxyl group. are potent anti-inflammatory agents.

They are converted into signaling molecules Meaning ∞ Signaling molecules are chemical messengers that transmit information between cells, precisely regulating cellular activities and physiological processes. called resolvins and protectins that actively resolve inflammation in the body. By incorporating sources of omega-3s into your diet, you can help modulate this inflammatory response, potentially easing some of the discomforts of menopause.

Healthy fats also aid in the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins ∞ A, D, E, and K ∞ which are involved in everything from immune function and bone health to antioxidant protection. They also contribute to satiety, helping you feel full and satisfied after meals, which is a key component of sustainable weight management.

The strategic inclusion of these three macronutrients forms the cornerstone of a physiological strategy to navigate menopause with strength and grace. It is a process of providing your body with the precise tools it needs to find its new equilibrium. This is not about restriction; it is about intentional nourishment. It is about understanding the language of your own biology and learning to respond with wisdom and care.

Intermediate

Advancing beyond the foundational understanding of macronutrients requires a more granular examination of their biochemical roles and their direct influence on the interconnected hormonal pathways that are in flux during menopause. The conversation shifts from what each macronutrient does to how it achieves its effects.

The menopausal body is operating under a new set of rules, dictated by the withdrawal of high levels of estrogen. This hormonal shift creates a domino effect, altering insulin sensitivity, cortisol regulation, and inflammatory signaling. A sophisticated nutritional strategy recognizes this new internal environment and uses macronutrients as precision tools to modulate these interconnected systems.

It is a clinical approach to diet, where food choices are made with a clear understanding of their physiological consequences. This allows for a proactive stance, using nutrition to guide the body toward a state of balanced function.

Protein Quality and Amino Acid Signaling

The simple recommendation to consume adequate protein evolves into a more nuanced discussion about protein quality and the specific roles of its constituent amino acids. Protein quality is determined by its amino acid profile and bioavailability. Complete proteins, which contain all nine essential amino acids, are particularly important.

These are typically found in animal sources like lean meats, fish, eggs, and dairy, as well as in some plant sources like soy and quinoa. During menopause, the amino acid leucine takes on a special significance. Leucine is a branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) that acts as a powerful signaling molecule, directly activating the mTOR pathway in muscle cells.

This pathway is a master regulator of muscle protein synthesis. Consuming a leucine-rich protein source, particularly after physical activity, provides a potent stimulus for muscle maintenance and growth, directly counteracting the sarcopenic effects of estrogen decline.

Beyond muscle, specific amino acids are precursors to key neurotransmitters that are heavily influenced by hormonal changes. The amino acid tryptophan is the precursor to serotonin, a neurotransmitter that regulates mood, sleep, and appetite. Estrogen helps regulate serotonin production and receptor function.

As estrogen levels decline, many women experience mood disturbances and sleep issues that are linked to this dysregulation. Consuming adequate tryptophan from protein sources like turkey, nuts, and seeds can support the brain’s ability to produce serotonin. Similarly, the amino acid tyrosine is the precursor to dopamine and norepinephrine, neurotransmitters that govern motivation, focus, and alertness.

Supporting the production of these catecholamines through diet can help mitigate the cognitive fog and low motivation that some women experience during this transition. This demonstrates how a protein-rich diet functions on multiple levels, providing structural support, metabolic benefits, and the building blocks for neurological health.

How Does Protein Intake Affect Metabolic Rate?

Protein’s influence on metabolic rate is a key lever for managing body composition during menopause. The thermic effect of food (TEF) for protein is approximately 20-30%, meaning that 20-30% of the calories from protein are expended during its digestion and metabolism. This is substantially higher than the TEF for carbohydrates (5-10%) and fats (0-3%).

A diet with a higher proportion of protein thus naturally increases daily energy expenditure. This metabolic advantage is compounded by protein’s effect on satiety. Protein stimulates the release of several gut hormones, including peptide YY (PYY) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), which signal fullness to the brain. This enhanced satiety helps regulate appetite and reduce overall calorie intake without inducing feelings of deprivation, a critical factor for long-term adherence to any nutritional plan.

The strategic consumption of specific carbohydrates can directly influence cortisol levels, the body’s primary stress hormone, which is often dysregulated during the menopausal transition.

Carbohydrate Precision the Glycemic Index and Cortisol Connection

A sophisticated approach to carbohydrates moves beyond the simple dichotomy of “good” versus “bad” and focuses on the concept of glycemic load. The glycemic load Meaning ∞ Glycemic Load, or GL, quantifies the estimated impact of a specific food portion on an individual’s blood glucose levels, integrating both the food’s carbohydrate content per serving and its glycemic index. (GL) of a food accounts for both the quality (glycemic index) and quantity of carbohydrates in a serving.

Managing the glycemic load of your meals is paramount for controlling the insulin response. During menopause, the body’s ability to handle glucose is often impaired. Chronic high insulin levels, resulting from a diet high in high-GL foods, not only promote fat storage but also drive inflammation. Insulin resistance Meaning ∞ Insulin resistance describes a physiological state where target cells, primarily in muscle, fat, and liver, respond poorly to insulin. is closely linked to elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines, which can worsen menopausal symptoms Meaning ∞ Menopausal symptoms represent a collection of physiological and psychological manifestations experienced by individuals during the menopausal transition, primarily driven by the decline in ovarian hormone production, notably estrogen and progesterone. like hot flashes and joint pain.

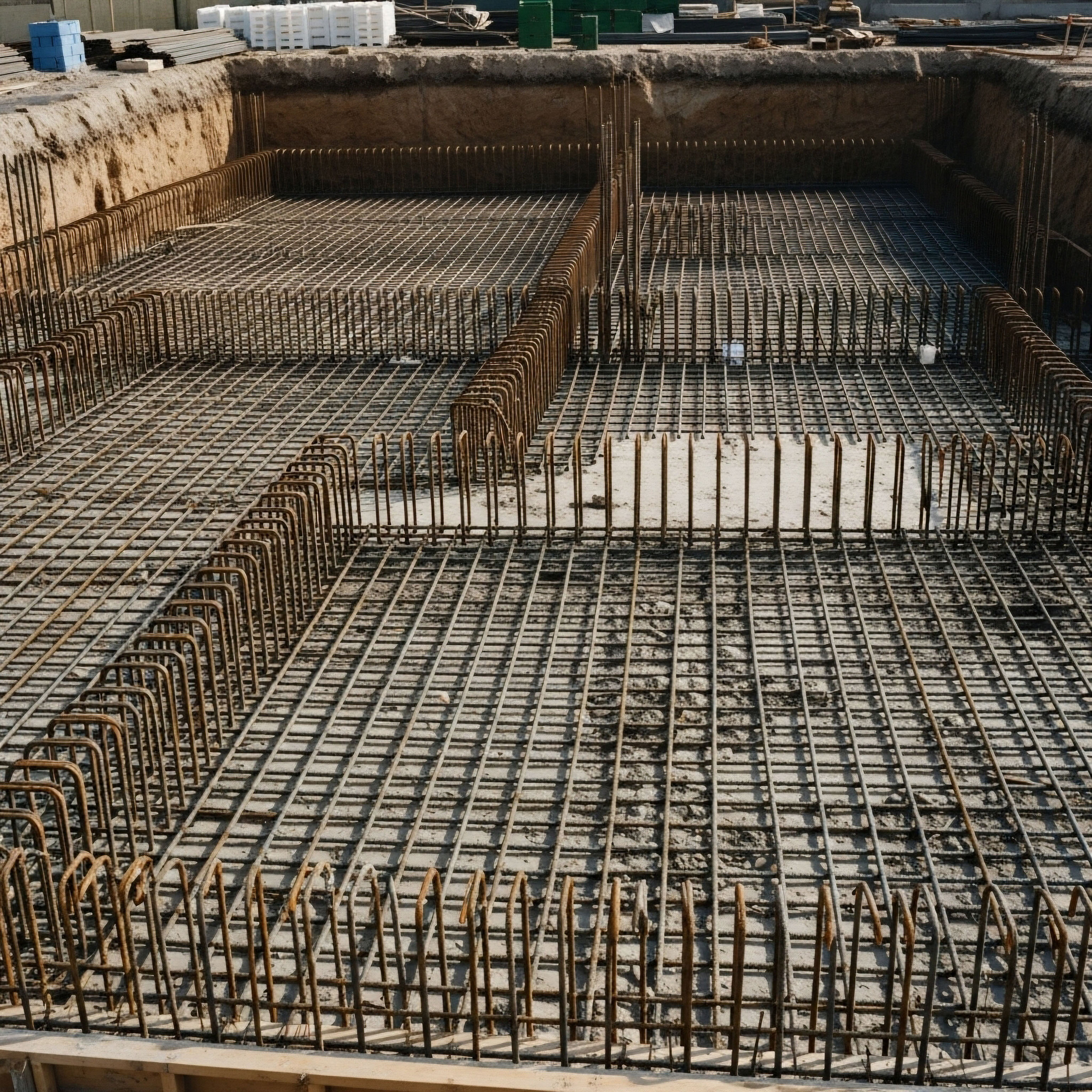

The connection between carbohydrate intake and the stress hormone cortisol is another critical consideration. The HPA (Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal) axis, which governs the stress response, becomes more sensitive during menopause. Sharp drops in blood sugar, which can occur after a high-glycemic meal or from overly restricting carbohydrates, are perceived by the body as a stressor.

This triggers the release of cortisol. Chronically elevated cortisol can lead to increased central adiposity (belly fat), further muscle breakdown, and disrupted sleep patterns, creating a vicious cycle. Consuming low-glycemic, high-fiber carbohydrates at regular intervals helps to maintain stable blood sugar, preventing these cortisol surges. This strategic use of carbohydrates can help soothe a reactive HPA axis, promoting a greater sense of calm and stability.

| Macronutrient | Optimal Sources | Primary Clinical Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Protein | Lean poultry, fatty fish (salmon), eggs, Greek yogurt, lentils, tofu | Preserves lean muscle mass, boosts metabolic rate, enhances satiety, provides amino acids for neurotransmitter synthesis. |

| Carbohydrates | Quinoa, oats, sweet potatoes, berries, leafy greens, beans | Stabilizes blood sugar and insulin levels, supports gut health and the estrobolome, helps regulate cortisol response. |

| Fats | Avocado, olive oil, walnuts, chia seeds, flaxseeds, almonds | Provides building blocks for hormones, reduces inflammation, supports brain health and cell membrane integrity. |

Fats as Signaling Molecules the Omega-3 to Omega-6 Ratio

The function of dietary fats Meaning ∞ Dietary fats are macronutrients derived from food sources, primarily composed of fatty acids and glycerol, essential for human physiological function. extends into the realm of intracellular signaling. Polyunsaturated fats are categorized into two main families ∞ omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids. Both are essential, meaning the body cannot produce them. However, they are precursors to different families of eicosanoids, which are powerful, localized signaling molecules that regulate inflammation, blood clotting, and blood vessel constriction.

The typical Western diet is overwhelmingly high in omega-6 fatty acids (found in many vegetable oils like corn, soybean, and sunflower oil) and low in omega-3s. This imbalance promotes the production of pro-inflammatory eicosanoids from omega-6s, creating a chronic, low-grade inflammatory state. This systemic inflammation can amplify many menopausal symptoms, particularly vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes) and musculoskeletal pain.

Consciously shifting this ratio by decreasing the intake of processed foods and industrial seed oils while increasing the intake of omega-3-rich foods is a powerful therapeutic strategy. The omega-3 fatty acids EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) and DHA (docosahexaenoic acid), found primarily in fatty fish, are particularly potent.

EPA is a direct competitor to the omega-6 arachidonic acid, reducing the production of inflammatory signals. DHA is a primary structural component of the brain and retina, and adequate levels are critical for maintaining cognitive function and mood stability. For women experiencing mood lability or cognitive changes, ensuring a rich supply of DHA is a key nutritional objective.

This targeted approach to fat consumption allows you to directly influence the inflammatory tone of your body, creating a more stable internal environment.

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids ∞ Found in salmon, mackerel, sardines, flaxseeds, and walnuts, these fats are converted into anti-inflammatory compounds, supporting cardiovascular and cognitive health.

- Monounsaturated Fats ∞ Abundant in olive oil, avocados, and almonds, these fats support healthy cholesterol levels and improve insulin sensitivity.

- Saturated Fats ∞ Present in coconut oil and animal fats, these should be consumed in moderation, prioritizing whole-food sources over processed ones.

Academic

A deep, academic exploration of macronutrient influence on menopausal hormonal balance requires a systems-biology perspective, moving beyond isolated effects to analyze the intricate feedback loops between nutrient sensing pathways, metabolic hormones, and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. The withdrawal of estradiol during menopause is not a simple event; it is a systemic shock that perturbs multiple homeostatic mechanisms.

The body’s response to this perturbation is heavily conditioned by its metabolic status, which is, in turn, dictated by macronutrient intake. The central thesis of this advanced analysis is that macronutrient composition functions as a chronic modulator of the key cellular signaling nodes ∞ namely mTOR, AMPK, and insulin/IGF-1 signaling ∞ which collectively determine the phenotype of the menopausal transition.

The symptomatology experienced by an individual can be viewed as the emergent property of the interaction between their unique genetic predispositions and the metabolic environment sculpted by their diet.

Macronutrients and the Insulin-Glucose-Adipokine Axis

The decline in estrogen induces a state of relative insulin resistance, independent of other factors. Estrogen normally has a beneficial effect on glucose uptake in peripheral tissues. Its absence predisposes women to hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia. A diet characterized by a high glycemic load chronically activates the insulin/IGF-1 signaling pathway.

This has profound consequences. Persistent hyperinsulinemia downregulates the production of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) in the liver, leading to higher levels of free circulating androgens. This can contribute to symptoms like acne and hirsutism, and it alters the overall hormonal milieu. Furthermore, the resulting visceral adipose tissue Meaning ∞ Visceral Adipose Tissue, or VAT, is fat stored deep within the abdominal cavity, surrounding vital internal organs. (VAT) accumulation is a critical factor.

VAT is not an inert storage depot; it is a highly active endocrine organ that secretes a variety of adipokines, including leptin, adiponectin, and inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6.

This “adiposopathy” creates a self-perpetuating cycle of inflammation and metabolic dysfunction. The inflammatory cytokines secreted by VAT further impair insulin signaling in muscle and liver tissue, exacerbating insulin resistance. Leptin resistance, a common consequence of obesity, disrupts hypothalamic signaling related to satiety and energy expenditure.

Conversely, adiponectin, which has insulin-sensitizing and anti-inflammatory properties, is downregulated in states of increased adiposity. A dietary strategy centered on low-glycemic carbohydrates and adequate fiber directly targets this pathological axis. By minimizing postprandial glucose and insulin excursions, such a diet reduces the stimulus for VAT accumulation and can improve adipokine profiles.

High-fiber intake also modulates the gut microbiota, which has been shown to influence systemic inflammation and insulin sensitivity Meaning ∞ Insulin sensitivity refers to the degree to which cells in the body, particularly muscle, fat, and liver cells, respond effectively to insulin’s signal to take up glucose from the bloodstream. through the production of short-chain fatty acids like butyrate.

How Do Fatty Acids Modulate Cellular Inflammation?

The molecular mechanism by which dietary fats modulate inflammation involves the competitive metabolism of omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) by the cyclooxygenase (COX) and lipoxygenase (LOX) enzymes. The omega-6 PUFA arachidonic acid (AA) is the substrate for the synthesis of pro-inflammatory series-2 prostaglandins (e.g.

PGE2) and series-4 leukotrienes. These eicosanoids are potent mediators of pain, fever, and vascular permeability, and are implicated in the pathophysiology of vasomotor symptoms. The omega-3 PUFA eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) competes with AA for the same enzymes. When EPA is metabolized, it produces series-3 prostaglandins and series-5 leukotrienes, which are significantly less inflammatory or are actively anti-inflammatory.

Furthermore, omega-3 PUFAs are precursors to a specialized class of lipid mediators known as Specialized Pro-resolving Mediators (SPMs), including resolvins, protectins, and maresins. These molecules play an active role in the resolution of inflammation, a process distinct from simple anti-inflammatory blockade. They orchestrate the clearance of cellular debris and promote tissue healing.

A diet with a low omega-6 to omega-3 ratio therefore shifts the entire lipid mediator landscape from a pro-inflammatory to a pro-resolving state, offering a powerful intervention to mitigate the heightened inflammatory tone of menopause.

| Intervention | Key Biomarkers Affected | Observed Clinical Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Protein Diet (35-40% of calories) | Increased GLP-1 and PYY; Decreased Ghrelin; Increased Resting Metabolic Rate | Improved satiety, preservation of lean body mass during weight loss, reduced overall caloric intake. |

| Low-Glycemic Load Diet | Reduced postprandial insulin and glucose; Decreased C-Reactive Protein (CRP) and IL-6 | Reduced frequency and severity of vasomotor symptoms, improved insulin sensitivity, weight management. |

| Increased Omega-3 Fatty Acid Intake | Decreased AA/EPA ratio; Reduced PGE2 synthesis; Increased SPM production | Reduction in depressive symptoms, decreased joint pain, improvement in markers of cardiovascular risk. |

The Role of Amino Acids in Neuroendocrine Regulation

The neurobiological impact of macronutrient choices during menopause is a field of growing interest. The decline in estrogen significantly impacts the synthesis and signaling of key neurotransmitters, including serotonin, dopamine, and GABA. This contributes to the increased prevalence of depression, anxiety, and cognitive disturbances during this period.

Dietary protein provides the precursor amino acids for these neurotransmitters. Tryptophan competes with other large neutral amino acids (LNAAs), including the BCAAs, for transport across the blood-brain barrier (BBB). A high-protein meal can paradoxically lower brain tryptophan levels by increasing the plasma concentration of competing LNAAs.

However, a meal that combines complex carbohydrates with a moderate amount of protein can facilitate brain tryptophan uptake. The insulin release stimulated by the carbohydrates promotes the uptake of BCAAs into muscle tissue, reducing their competition with tryptophan at the BBB. This allows for increased serotonin synthesis, which can have a stabilizing effect on mood and sleep.

The integrity of the gut-brain axis is also a critical factor. The gut microbiota metabolizes dietary fiber to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). These SCFAs, particularly butyrate, have neuroprotective effects and can influence neurotransmitter production. A healthy, diverse microbiome, fostered by a fiber-rich diet, can therefore support neuroendocrine stability.

This intricate interplay highlights the necessity of a holistic dietary approach. It is not simply about one macronutrient, but about the synergistic effect of a well-formulated dietary pattern that simultaneously manages glycemic load, optimizes fatty acid profiles, provides adequate protein, and nourishes the gut microbiome. This integrated strategy provides the most robust support for the body’s complex adaptation to the hormonal realities of menopause.

- Protein Distribution ∞ The timing of protein intake, particularly ensuring an adequate bolus (25-30g) at each main meal, is critical for stimulating muscle protein synthesis throughout the day.

- Fiber Diversity ∞ Consuming a wide variety of fiber types (soluble, insoluble, prebiotic) from different plant sources is essential for cultivating a diverse and resilient gut microbiome.

- Mindful Fat Selection ∞ The focus should be on whole-food sources of fats, such as avocados, nuts, and seeds, which provide a complex matrix of nutrients in addition to the fatty acids themselves.

References

- Te-Fu Tsai, et al. “Effect of Soy Isoflavone on Menopausal Symptoms, Endometrium, and Breast in Postmenopausal Women ∞ A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study.” Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, vol. 110, no. 5, 2011, pp. 299-307.

- Simin Blourchian, et al. “The effect of soy isoflavones on hot flashes and bone mineral density in menopausal women ∞ a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Journal of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, vol. 8, no. 1, 2020, pp. 2063-2074.

- Lori A. T. Thomas, et al. “The Effect of a High-Protein Diet on Mood, Menopausal Symptoms, and Quality of Life in Postmenopausal Women.” Menopause, vol. 24, no. 10, 2017, pp. 1133-1139.

- Westerterp-Plantenga, Margriet S. “Protein intake and energy balance.” Regulatory Peptides, vol. 149, no. 1-3, 2008, pp. 67-69.

- Freeman, Marlene P. et al. “Omega-3 fatty acids and menopause ∞ a review.” Menopause, vol. 13, no. 4, 2006, pp. 723-730.

- Davis, S. R. et al. “Understanding weight gain at menopause.” Climacteric, vol. 15, no. 5, 2012, pp. 419-429.

- Silva, Thais R. et al. “The role of nutrition in the management of menopausal symptoms ∞ a narrative review.” Maturitas, vol. 139, 2020, pp. 98-105.

- Mohammad-Rezaeizadeh, Hossein, et al. “The effect of isoflavones on menopausal symptoms ∞ a systematic review.” Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, vol. 19, no. 9, 2014, pp. 883-891.

Reflection

Charting Your Own Biological Course

The information presented here provides a map of the physiological territory of menopause, detailing how the fundamental elements of nutrition interact with your body’s shifting hormonal landscape. This knowledge is a powerful tool, transforming abstract feelings of change into understandable biological processes.

You now have a framework for understanding why your body may be responding in new ways and how your choices at every meal can become a form of communication with your own endocrine system. This is the first, essential step ∞ the transition from being a passenger in your own health journey to becoming the pilot.

The path forward is one of self-discovery and personalization. The principles discussed ∞ supporting muscle with protein, stabilizing energy with fiber-rich carbohydrates, and cooling inflammation with healthy fats ∞ are the universal guidelines. Your unique task is to apply them within the context of your own life, your own preferences, and your own body’s distinct responses.

This is an invitation to become a careful observer of yourself, to notice how different foods and meal structures make you feel, both physically and mentally. The ultimate goal is to create a personalized protocol that is both scientifically sound and deeply sustainable for you. This journey of recalibration is an opportunity to forge a new, more profound relationship with your body, one built on a foundation of scientific understanding and compassionate self-awareness.