Fundamentals

You feel it in your body ∞ a shift in energy, a change in mood, a sense that your internal settings are no longer calibrated to your life. This experience, this intimate awareness of your own biological state, is the most valid data point you have.

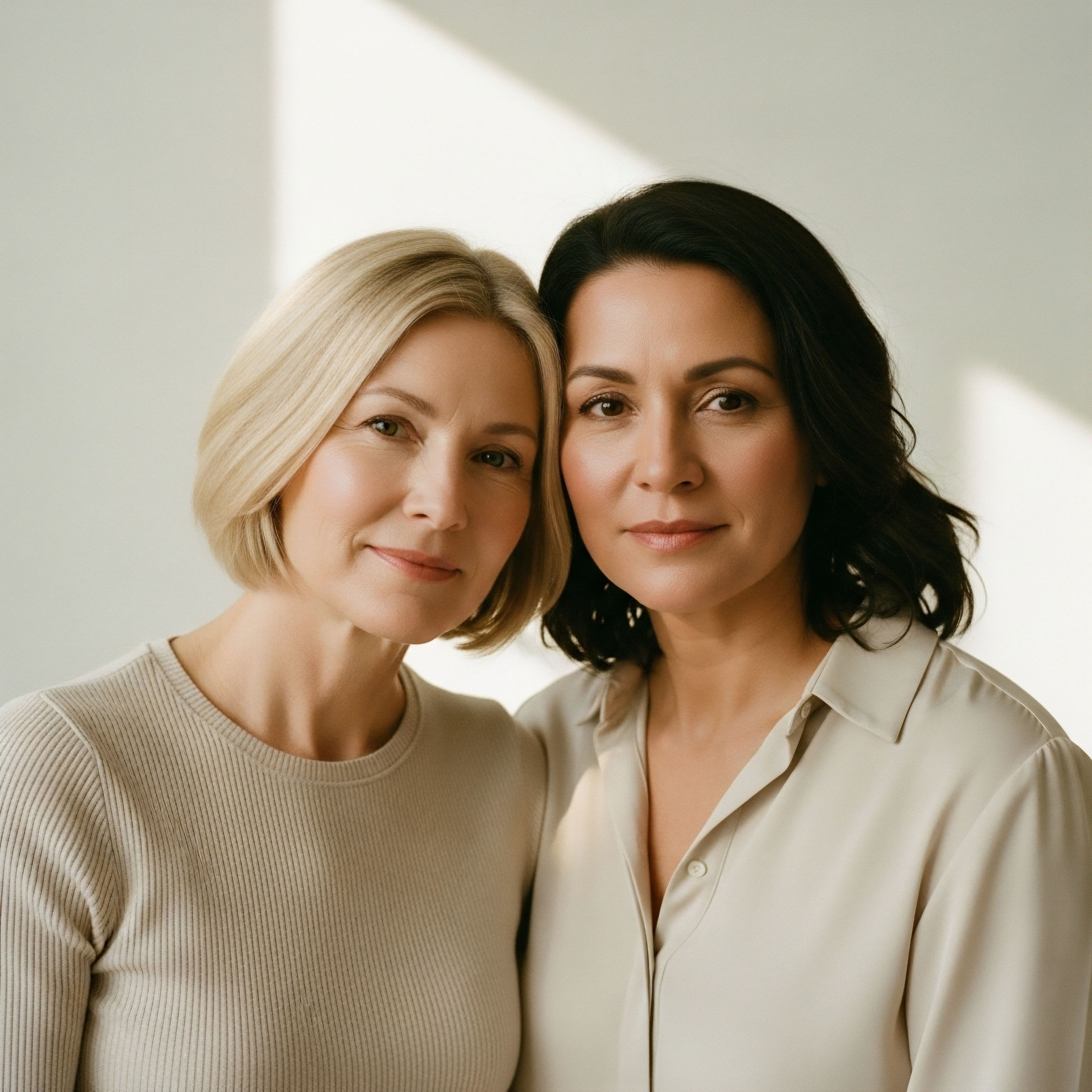

When we discuss how what you eat affects your hormonal balance, we are starting with that lived reality. The question of how specific dietary choices influence estrogen in men versus women is a profound one because it speaks to the very core of our vitality, mood, and long-term health.

The food on your plate is not merely fuel; it is a set of instructions, sending biochemical signals that can either support or disrupt the delicate conversation happening within your endocrine system. Understanding this dialogue is the first step toward reclaiming control over your biological blueprint.

At the center of this conversation is estrogen, a hormone often associated with female physiology but which plays a vital role in both sexes. In women, it governs the reproductive cycle, bone density, and cardiovascular health. In men, estrogen is essential for modulating libido, erectile function, and sperm production.

The body’s ability to maintain estrogen within an optimal range is a dynamic process of production, utilization, and, critically, elimination. It is this final step ∞ elimination or detoxification ∞ where dietary interventions exert their most significant influence. Your nutritional choices directly impact how efficiently your body clears out used estrogens, preventing the accumulation that can lead to hormonal imbalance in both men and women.

Your diet provides the essential tools your body needs to properly metabolize and excrete hormones, directly influencing your internal estrogen balance.

Consider the liver as the primary sorting facility for your body’s hormonal mail. After estrogen has delivered its message to the cells, it is sent to the liver to be packaged for removal. Certain foods provide the raw materials that allow the liver to perform this function effectively.

Cruciferous vegetables, for instance, contain compounds that support the liver’s detoxification pathways, ensuring estrogen is neutralized and tagged for excretion. Conversely, other lifestyle factors, such as alcohol consumption, can impair this process. The liver prioritizes metabolizing alcohol, effectively putting its estrogen-clearing duties on hold, which can lead to a backlog and elevated levels in the bloodstream. This dynamic is true for both male and female physiology, though the clinical consequences of excess estrogen may manifest differently.

This introduces a foundational principle of hormonal health ∞ your body’s internal environment is profoundly shaped by external inputs. The symptoms you may be experiencing ∞ fatigue, weight gain, mood swings, or low libido ∞ are often signals of a systemic imbalance. By understanding how specific foods interact with your unique physiology, you begin a personal journey of biochemical recalibration.

This is a process of learning to listen to your body and responding with targeted, evidence-based nutritional strategies that restore function and vitality from the inside out.

Intermediate

Moving beyond foundational concepts, we can begin to dissect the precise mechanisms through which dietary choices modulate estrogen levels. This requires an appreciation for the body’s intricate systems of hormonal communication and clearance, particularly the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis and the metabolic pathways within the liver and gut.

Your daily food intake directly interfaces with these systems, acting as a powerful modulator of your endocrine function. For men and women alike, mastering these inputs is key to achieving hormonal equilibrium.

The Role of Phytoestrogens a Complex Relationship

Phytoestrogens are plant-derived compounds with a chemical structure similar to the body’s own estrogen, allowing them to interact with estrogen receptors. This interaction is complex; they can exert either a weak estrogenic (agonist) or an anti-estrogenic (antagonist) effect depending on the hormonal environment. The two primary classes of phytoestrogens Meaning ∞ Phytoestrogens are plant-derived compounds structurally similar to human estrogen, 17β-estradiol. are isoflavones, found abundantly in soy products, and lignans, which are concentrated in flaxseeds, sesame seeds, and whole grains.

- In Women During the reproductive years, when endogenous estrogen levels are high, phytoestrogens can compete with the body’s more potent estrogen for receptor binding sites. This competitive inhibition results in a net anti-estrogenic effect, which can be beneficial in conditions of estrogen excess. In postmenopausal women, where endogenous estrogen is low, these same phytoestrogens can provide a weak estrogenic signal, potentially mitigating some symptoms associated with menopause.

- In Men The concern for men often revolves around the potential for estrogenic effects from phytoestrogens to disrupt the testosterone-to-estrogen ratio. However, the existing body of clinical research does not consistently support this fear with moderate consumption. The weak binding affinity of most phytoestrogens means they are unlikely to cause significant feminizing effects. Some research even suggests a protective role against prostate conditions due to their modulatory effects.

Cruciferous Vegetables and Estrogen Detoxification

One of the most powerful dietary interventions for hormonal health involves the consumption of cruciferous vegetables Meaning ∞ Cruciferous vegetables are a distinct group of plants belonging to the Brassicaceae family, characterized by their four-petal flowers resembling a cross. like broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, and cabbage. These vegetables are rich in a glucosinolate called glucobrassicin, which, upon chewing and digestion, yields a compound named Indole-3-Carbinol (I3C). In the acidic environment of the stomach, I3C is converted into several active metabolites, most notably 3,3′-Diindolylmethane (DIM).

Both I3C and DIM are instrumental in supporting the liver’s Phase I and Phase II detoxification pathways. They help steer estrogen metabolism Meaning ∞ Estrogen metabolism refers to the comprehensive biochemical processes by which the body synthesizes, modifies, and eliminates estrogen hormones. toward the production of less potent and more easily excreted estrogen metabolites. This process is critical for both sexes. For women, efficient estrogen clearance is associated with a lower risk of estrogen-sensitive conditions. For men, it helps maintain a healthy balance between testosterone and estrogen, as excess testosterone can be converted to estrogen via the aromatase enzyme.

Compounds from cruciferous vegetables act as traffic controllers for estrogen metabolism, guiding it down healthier, less potent pathways in the liver.

The table below outlines the primary mechanisms of key dietary components on estrogen metabolism.

| Dietary Component | Primary Active Compound | Mechanism of Action | Primary Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soy Products | Isoflavones (e.g. Genistein) | Binds to estrogen receptors, acting as a Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulator (SERM). | Can exert weak estrogenic or anti-estrogenic effects depending on endogenous hormone levels. |

| Flaxseeds | Lignans | Metabolized by gut bacteria into enterolactone and enterodiol, which have weak estrogenic activity. | Modulates estrogen activity and supports healthy metabolism. |

| Cruciferous Vegetables | Indole-3-Carbinol (I3C) & DIM | Promotes favorable estrogen metabolism pathways in the liver (Phase I & II detoxification). | Enhances clearance of potent estrogens, supporting hormonal balance in both sexes. |

| Dietary Fiber | Insoluble and Soluble Fiber | Binds to estrogens in the gut and modulates the estrobolome, reducing reabsorption. | Increases fecal excretion of estrogen, lowering circulating levels. |

How Does Dietary Fiber Influence the Estrobolome?

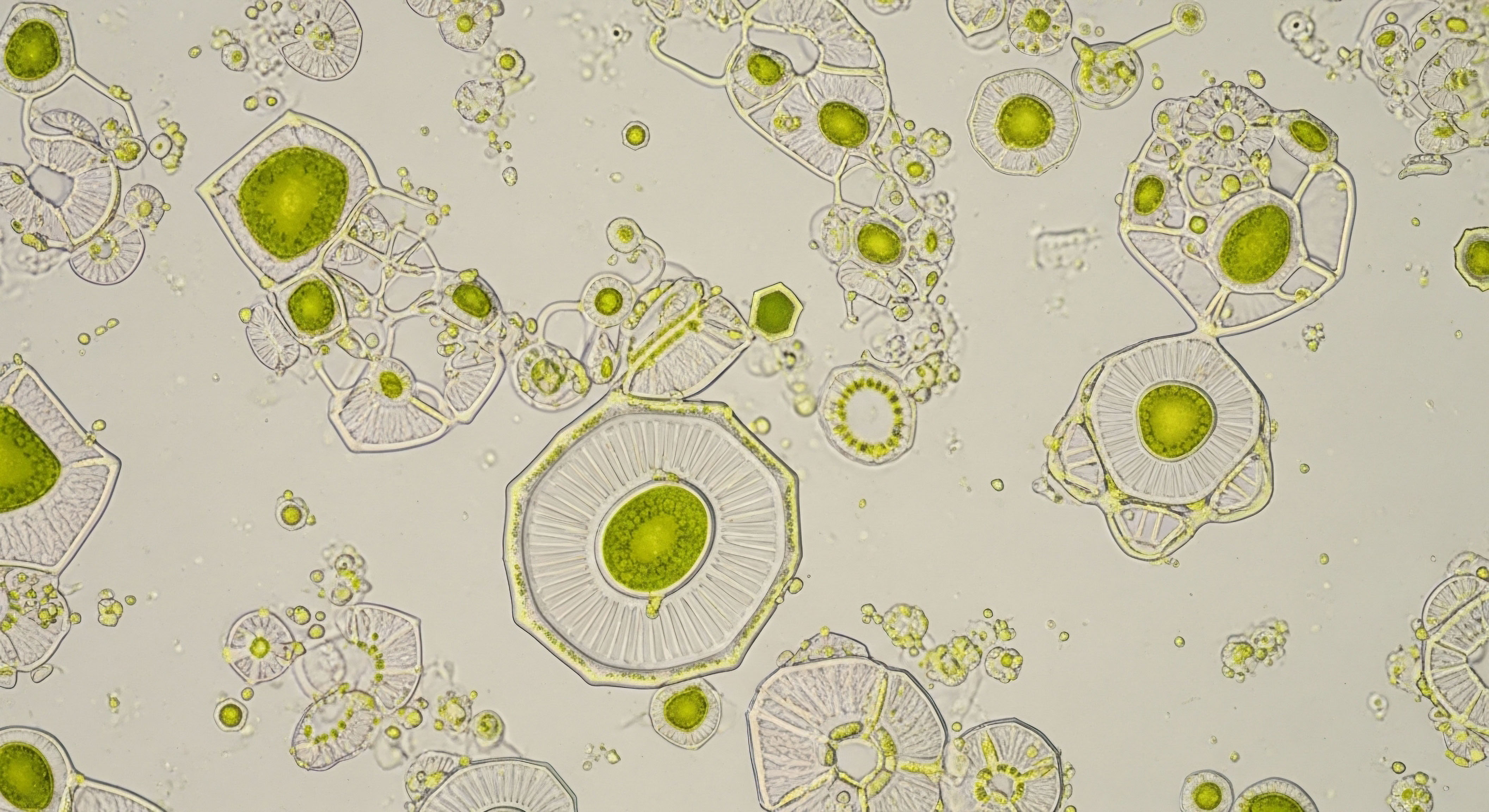

The gut microbiome Meaning ∞ The gut microbiome represents the collective community of microorganisms, including bacteria, archaea, viruses, and fungi, residing within the gastrointestinal tract of a host organism. contains a specific collection of bacteria, termed the “estrobolome,” that produces an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase. This enzyme can “reactivate” estrogens that have been conjugated (packaged for removal) by the liver and sent to the gut for excretion.

High levels of beta-glucuronidase activity lead to more estrogen being reabsorbed back into circulation, raising overall estrogen levels. A diet rich in fiber has a profound impact on this process. Fiber increases the bulk and transit time of stool, which helps to bind and excrete estrogens before they can be reabsorbed.

Furthermore, certain fibers act as prebiotics, feeding beneficial gut bacteria that help maintain a healthy balance within the estrobolome, thereby reducing the activity of beta-glucuronidase. This mechanism is equally important for men and women seeking to optimize their hormonal health.

Academic

A sophisticated understanding of dietary influence on estrogen levels Meaning ∞ Estrogen levels denote the measured concentrations of steroid hormones, predominantly estradiol (E2), estrone (E1), and estriol (E3), circulating within an individual’s bloodstream. requires a systems-biology perspective, integrating endocrinology, gastroenterology, and molecular biology. The primary regulatory interface between diet and estrogen is not a single point but a network of interconnected metabolic pathways.

These include the hepatic metabolism of steroids, the enzymatic activity of the gut’s estrobolome, and the availability of precursor molecules for hormone synthesis. The differential impact on men and women arises from their distinct baseline hormonal milieus and the physiological consequences of altering the androgen-to-estrogen ratio.

Hepatic Cytochrome P450 Enzymes and Estrogen Metabolism

The metabolism of estradiol (E2), the most potent endogenous estrogen, is primarily carried out in the liver by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) family of enzymes. This process, known as hydroxylation, can proceed down several pathways, producing metabolites with varying degrees of estrogenic activity. The two principal pathways are:

- The 2-hydroxylation pathway (CYP1A1/1A2) This pathway produces 2-hydroxyestrone (2-OHE1), a metabolite with very weak estrogenic activity that is considered protective. It is readily conjugated and excreted from the body.

- The 16α-hydroxylation pathway (CYP3A4) This pathway yields 16α-hydroxyestrone (16α-OHE1), a metabolite that retains significant estrogenic activity and has been implicated in promoting cellular proliferation.

Dietary compounds found in cruciferous vegetables, specifically Indole-3-Carbinol Meaning ∞ Indole-3-Carbinol, commonly referred to as I3C, is a naturally occurring compound derived from the breakdown of glucobrassicin, a sulfur-containing glucosinolate found abundantly in cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli, cabbage, and kale. (I3C) and its dimer Diindolylmethane (DIM), are potent inducers of the CYP1A family enzymes. By upregulating this pathway, I3C and DIM shift the balance of estrogen metabolism away from the production of the proliferative 16α-OHE1 and toward the benign 2-OHE1 metabolite.

This biochemical shift is advantageous for both sexes. In women, a higher ratio of 2-OHE1 to 16α-OHE1 is associated with a reduced risk of estrogen-dependent cancers. In men, promoting this pathway aids in the efficient clearance of estrogen derived from the aromatization of testosterone, thereby helping to maintain a favorable hormonal balance Meaning ∞ Hormonal balance describes the physiological state where endocrine glands produce and release hormones in optimal concentrations and ratios. and mitigating risks associated with estrogen excess, such as gynecomastia.

Dietary modulation of liver enzymes provides a direct molecular mechanism for altering the biological activity of estrogen metabolites.

The Estrobolome and Enterohepatic Recirculation

The concept of the estrobolome Meaning ∞ The estrobolome is the collection of gut bacteria that metabolize estrogens. represents a critical nexus between gut health and systemic hormonal balance. After hepatic conjugation (primarily glucuronidation), estrogens are excreted into the gut via bile. The estrobolome consists of gut microbes that possess β-glucuronidase genes.

The enzyme β-glucuronidase deconjugates these estrogens, liberating them into their active, unbound form, which can then be reabsorbed into the bloodstream through enterohepatic circulation. A diet low in fiber and high in processed foods can alter the composition of the gut microbiota, leading to an overgrowth of bacteria with high β-glucuronidase activity. This dysbiosis results in increased deconjugation and reabsorption of estrogens, contributing to a state of estrogen dominance.

Conversely, a high-fiber diet directly counteracts this mechanism in two ways. First, insoluble fiber increases fecal bulk and accelerates intestinal transit, reducing the time available for β-glucuronidase to act on conjugated estrogens. Second, soluble fibers and prebiotics promote the growth of beneficial bacteria (e.g.

Lactobacillus species), which can lower the pH of the colon and competitively inhibit the microbes responsible for high β-glucuronidase activity. This dietary strategy effectively reduces the enterohepatic recirculation of estrogens, lowering systemic exposure in both men and women.

The following table details the impact of specific dietary patterns on hormonal markers.

| Dietary Pattern | Key Components | Effect on Male Hormones | Effect on Female Hormones |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Fiber, Plant-Based | Whole grains, legumes, vegetables, fruits | May help optimize the testosterone-to-estrogen ratio by improving estrogen excretion. | Lowers circulating estrogen levels through increased fecal excretion and modulation of the estrobolome. |

| Western Diet | High in processed meats, refined grains, high-fat dairy | Associated with higher levels of circulating estrogen and lower testosterone. | Consistently associated with higher estrogen levels and increased risk of estrogen-dominant conditions. |

| Low-Fat Diet | Reduced intake of all fats | Systematic reviews show that low-fat diets may decrease total and free testosterone levels. | Some studies show a reduction in circulating estrogens, potentially beneficial for high-estrogen states. |

| Chronic Alcohol Consumption | Regular intake of alcoholic beverages | Can increase aromatase activity, converting more testosterone to estrogen, and impair liver clearance. | Increases circulating estradiol levels by impairing liver metabolism. |

What Is the Impact of Dietary Fat on Steroidogenesis?

The quantity and type of dietary fat can influence sex hormone levels, partly by providing the precursor for steroidogenesis cholesterol. Low-fat diets have been shown in some meta-analyses to be associated with modest reductions in total and free testosterone Meaning ∞ Total testosterone represents the sum of all testosterone molecules circulating in the bloodstream, encompassing both those bound to proteins and the small fraction that remains unbound. in men.

Since testosterone is the primary substrate for estrogen production in men via the aromatase Meaning ∞ Aromatase is an enzyme, also known as cytochrome P450 19A1 (CYP19A1), primarily responsible for the biosynthesis of estrogens from androgen precursors. enzyme, a significant reduction in testosterone could theoretically lead to lower estrogen levels. However, the clinical significance of this reduction is still under investigation. For women, particularly postmenopausal women, adipose tissue is a primary site of estrogen production.

Diets that lead to an increase in adiposity can therefore increase overall estrogen synthesis, creating a link between high-fat, high-calorie diets and elevated estrogen levels. The relationship is complex, as specific fatty acids may also have direct effects on enzyme activity within the steroidogenic pathways.

References

- Adlercreutz, H. “Phyto-oestrogens and cancer.” The Lancet Oncology, vol. 3, no. 6, 2002, pp. 364-73.

- Auborn, K. J. et al. “Indole-3-carbinol is a negative regulator of estrogen.” The Journal of nutrition, vol. 133, no. 7 Suppl, 2003, pp. 2470S-2475S.

- Baker, K. T. & Wetherill, Y. B. “The role of the estrobolome in breast cancer.” Endocrine-related cancer, vol. 25, no. 8, 2018, pp. R347-R360.

- Bradlow, H. L. et al. “2-hydroxyestrone ∞ the ‘good’ estrogen.” Journal of endocrinology, vol. 150, no. 3, 1996, pp. S259-65.

- Emanuele, M. A. & Emanuele, N. V. “Alcohol and the male reproductive system.” Alcohol research & health ∞ the journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, vol. 25, no. 4, 2001, pp. 282-7.

- Fowke, J. H. et al. “Brassica vegetable consumption shifts estrogen metabolism in healthy postmenopausal women.” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, vol. 9, no. 8, 2000, pp. 773-79.

- Ginsburg, E. S. et al. “Effects of alcohol ingestion on estrogens in postmenopausal women.” JAMA, vol. 276, no. 21, 1996, pp. 1747-51.

- Horn-Ross, P. L. et al. “Phytoestrogen consumption and breast cancer risk in a multiethnic population ∞ the Bay Area Breast Cancer Study.” American journal of epidemiology, vol. 154, no. 5, 2001, pp. 434-41.

- Kwa, M. et al. “The Intestinal Microbiome and Estrogen Receptor-Positive Female Breast Cancer.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 108, no. 8, 2016, p. djw029.

- Whittaker, J. & Wu, K. “Low-fat diets and testosterone in men ∞ Systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention studies.” The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology, vol. 210, 2021, p. 105878.

Reflection

You have now seen the intricate biological pathways that connect the food you consume to the hormonal signals that regulate your body. This knowledge is a powerful tool. It shifts the perspective from being a passive recipient of symptoms to becoming an active participant in your own wellness.

The journey to hormonal balance is deeply personal, as your unique genetics, lifestyle, and health history all contribute to how your body responds to these dietary instructions. The information presented here is a map, showing the established routes through which nutrition influences physiology. The next step is to consider your own starting point.

What aspects of this information resonate with your personal experience? Understanding the ‘why’ behind your body’s signals is the beginning of a more intentional and empowered approach to your health, a path where you are the one making the informed choices that will ultimately recalibrate your system toward vitality.