Fundamentals

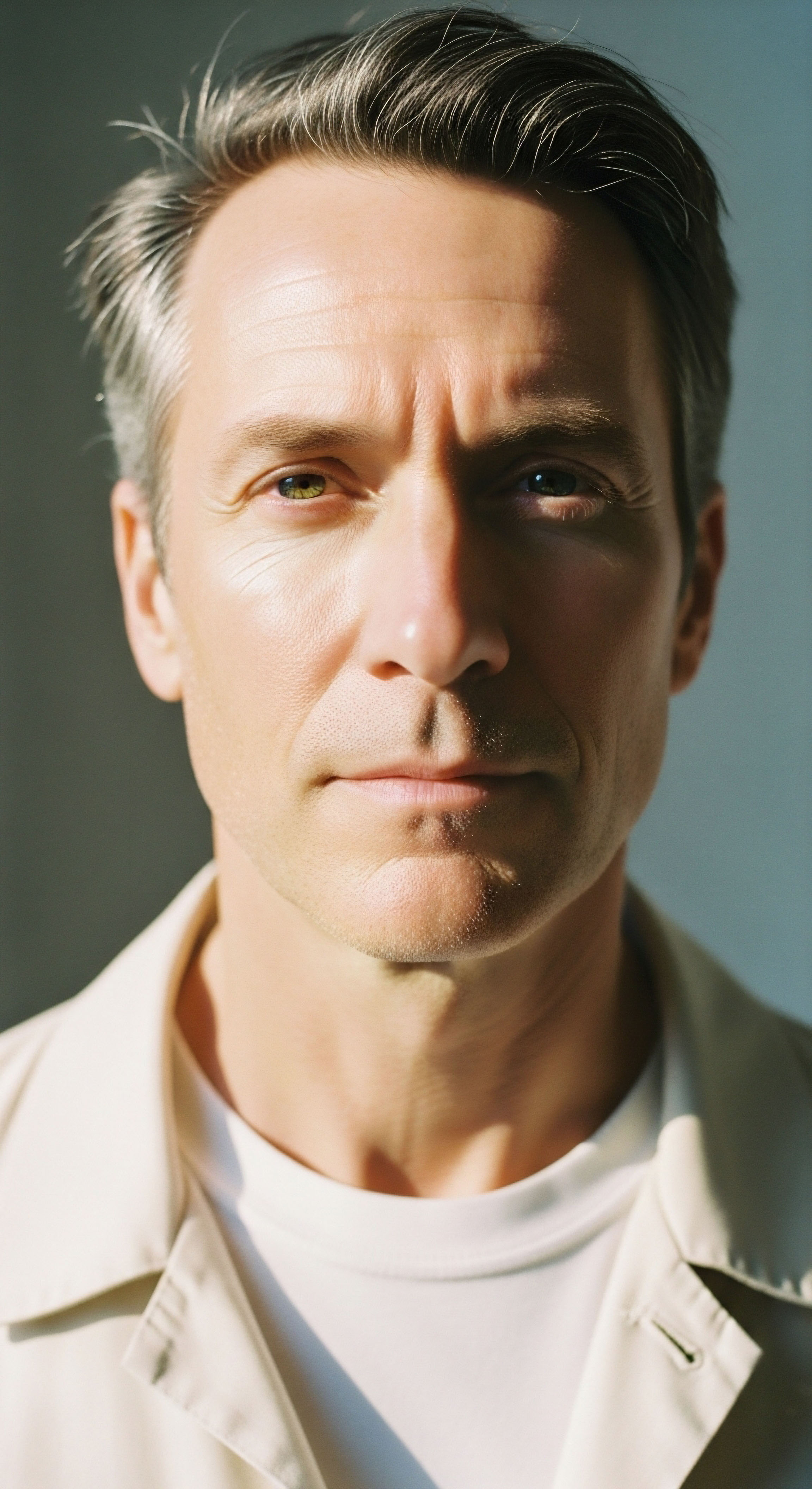

You feel it long before any lab test can confirm it. A persistent sense of fatigue that sleep does not seem to touch, a subtle shift in your body’s responses, and a mind that feels less sharp than it once was.

This experience, this lived reality of feeling misaligned with your own biology, is the starting point of a profound journey into your body’s inner world. Your body operates on an ancient, intricate rhythm, a daily cadence of activity and restoration orchestrated by the endocrine system. The conductor of this complex biological orchestra is your sleep-wake cycle. The quality and duration of your sleep directly determine the harmony or discord of your hormonal health.

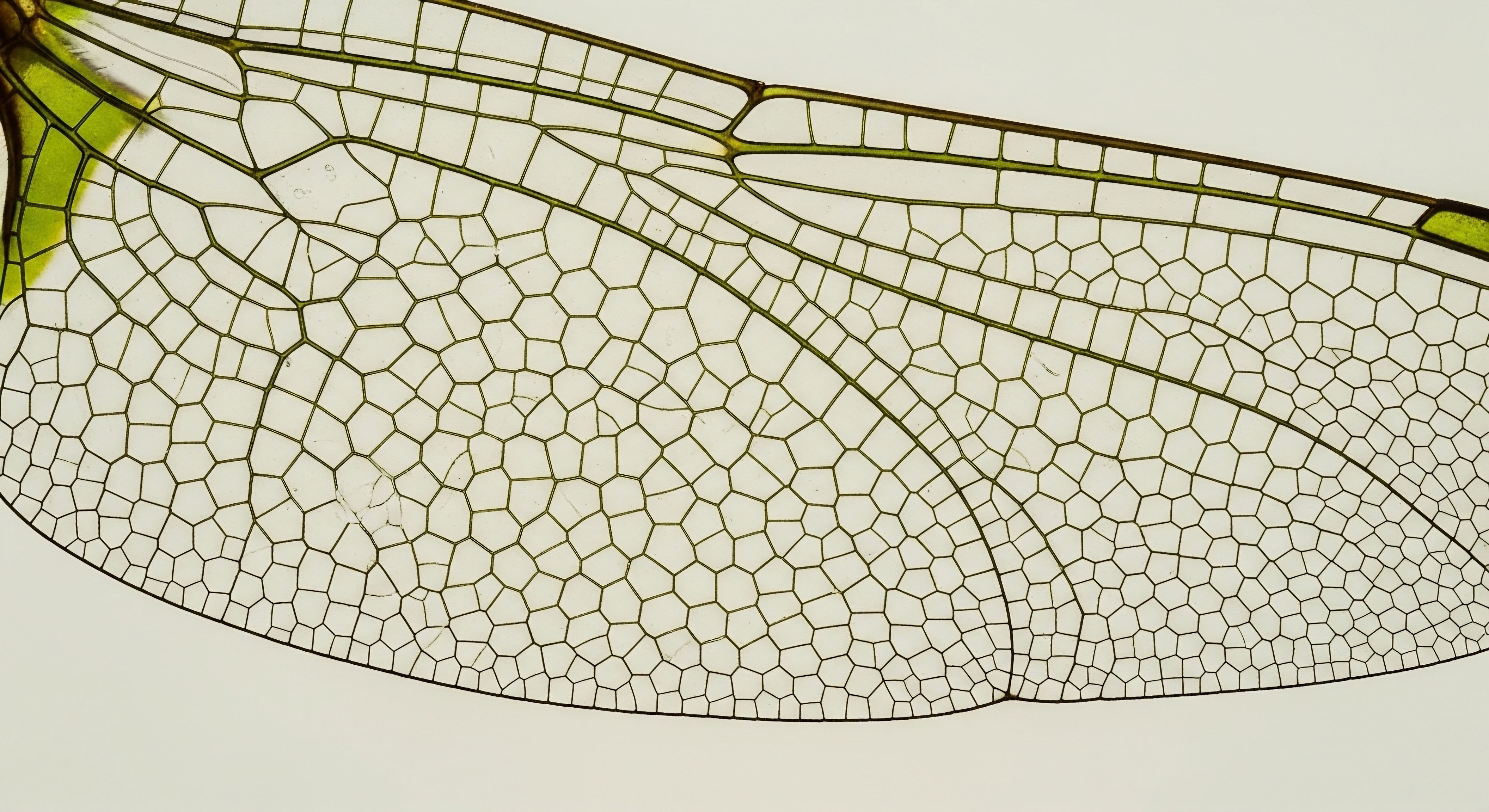

At the center of this regulation is the circadian rhythm, the body’s 24-hour internal clock. This master timekeeper, located in the hypothalamus region of the brain, dictates the precise timing for the release of nearly every hormone. When you sleep, your body is performing a vital, active process of cleansing and recalibration.

It is during these hours of restorative rest that the brain clears metabolic waste products accumulated during waking hours. Simultaneously, the endocrine glands engage in their most critical work, producing and balancing the chemical messengers that govern your energy, mood, metabolism, and cellular repair.

The Nightly Hormonal Reset

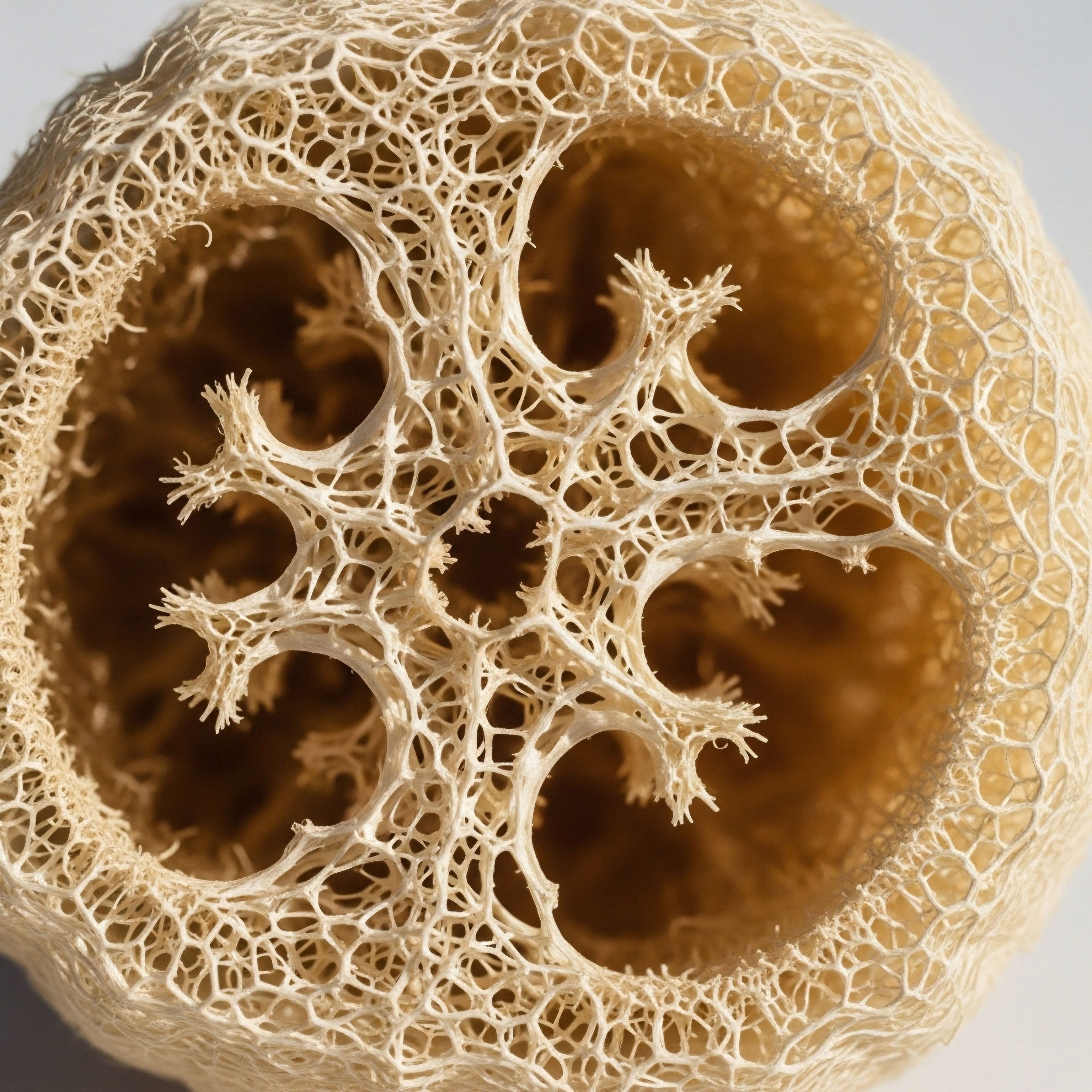

Think of your endocrine system as a sophisticated communication network. Hormones are the messages, and sleep is the period when the system performs its most important updates and maintenance. Several key hormones are profoundly influenced by the quality of your rest. Understanding their roles provides a foundation for appreciating the power of sleep interventions.

Cortisol the Rhythm of Alertness

Cortisol is often labeled the “stress hormone,” yet its function is far more elegant. It governs the body’s natural rhythm of energy and alertness. In a healthy cycle, cortisol levels are highest in the morning, providing the physiological impetus to wake up and engage with the day.

Throughout the day, these levels gradually decline, reaching their lowest point in the evening to prepare the body for sleep. Chronic sleep disruption inverts this pattern. Insufficient or fragmented rest can lead to elevated cortisol levels at night, creating a state of hyper-arousal that prevents the deep, restorative sleep necessary for recovery. This creates a self-perpetuating cycle of poor sleep and hormonal imbalance.

Growth Hormone the Architect of Repair

Human Growth Hormone (HGH) is the body’s primary agent of repair and regeneration. Its release is pulsatile, with the most significant surge occurring during the deep stages of sleep, often in the first few hours after you fall asleep. This powerful hormone is responsible for repairing tissues, building muscle, and maintaining healthy body composition.

When sleep is cut short or lacks sufficient deep-sleep stages, the primary window for HGH release is missed. The consequences manifest as slower recovery from exercise, difficulty maintaining muscle mass, and an increased tendency to store visceral fat, particularly around the abdomen.

Sleep is the active, nightly process that cleanses the brain and recalibrates the body’s entire hormonal network.

Your personal experience of waking up unrefreshed or feeling physically depleted is a direct reflection of these missed opportunities for biological repair. The feeling of sluggishness is your body communicating a deficit in its primary restorative process. Acknowledging this connection is the first step toward using sleep as a deliberate tool for reclaiming your vitality. The language of your body is spoken through these feelings of wellness or unease; learning to interpret it is central to navigating your own health.

Intermediate

Understanding that sleep governs hormonal health provides a powerful framework. The next step is to examine the specific biological machinery involved. Your body’s endocrine function is managed by intricate feedback loops, primarily the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. These systems are the central command centers for your stress response and reproductive health, respectively. Sleep quality acts as a master regulator for both, and its disruption sends destabilizing ripples throughout your entire physiology.

The HPA axis is your body’s stress-response system. The hypothalamus releases a hormone that signals the pituitary gland, which in turn signals the adrenal glands to produce cortisol. In a balanced state, this system activates in response to a threat and deactivates once the threat has passed.

Chronic sleep deprivation, however, keeps the HPA axis in a state of low-grade, persistent activation. This results in the elevated evening cortisol levels that interfere with sleep onset and quality, creating a vicious cycle. This sustained activation has systemic consequences, promoting inflammation and insulin resistance.

How Does Sleep Affect Male and Female Hormones Differently?

The HPG axis governs the production of sex hormones. While both men and women produce testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone, their balance and primary functions differ significantly. Sleep disruption affects the HPG axis in both sexes, but the manifestations are distinct. In men, a substantial portion of daily testosterone production occurs during sleep. For women, the intricate monthly dance of estrogen and progesterone is closely tied to the stability of the sleep-wake cycle.

| Hormonal System | Primary Effects in Men | Primary Effects in Women |

|---|---|---|

| Testosterone |

Reduced total and free testosterone levels. Symptoms include fatigue, low libido, decreased muscle mass, and mood disturbances. Consistent sleep restriction can lower testosterone levels by an amount equivalent to aging 10-15 years. |

Disruption in the testosterone-to-estrogen ratio. While testosterone is lower in women, it is vital for libido, bone density, and muscle maintenance. Imbalances can contribute to symptoms associated with perimenopause. |

| Estrogen & Progesterone |

Secondary effects related to the aromatization of testosterone to estrogen. Poor sleep can alter this balance, potentially leading to symptoms of estrogen dominance. |

Irregular menstrual cycles. Sleep disruption can interfere with the luteinizing hormone (LH) surge that triggers ovulation. It can also worsen symptoms of PMS and perimenopause, such as hot flashes and mood swings, as progesterone’s calming effects are diminished. |

The Metabolic Consequences of Poor Sleep

The hormonal impact of sleep loss extends directly to your metabolic health. The regulation of appetite and blood sugar is controlled by a trio of hormones ∞ leptin, ghrelin, and insulin. Efficient sleep keeps these three messengers in a delicate balance, promoting stable energy and healthy body composition.

A consistent sleep schedule is a non-negotiable foundation for stabilizing the body’s central hormonal command centers.

Leptin is the “satiety” hormone, produced by fat cells to signal to the brain that you are full. Ghrelin is the “hunger” hormone, released by the stomach to stimulate appetite. During a full night’s rest, leptin levels rise, and ghrelin levels fall, leaving you with a balanced appetite upon waking.

Sleep deprivation reverses this. It causes leptin levels to drop and ghrelin levels to spike. This biochemical shift creates a powerful craving for energy-dense, high-carbohydrate foods, even when the body does not require the additional calories. This explains the intense desire for sugary or processed foods after a night of poor sleep.

This imbalance is compounded by sleep’s effect on insulin, the hormone that manages blood sugar. Sleep loss induces a state of insulin resistance, meaning your cells become less responsive to insulin’s signals. Your pancreas must then produce more insulin to manage the same amount of glucose, leading to higher circulating insulin levels.

This state promotes fat storage and significantly increases the long-term risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. Addressing sleep is therefore a primary intervention for restoring metabolic function.

- Establish a Consistent Sleep-Wake Cycle ∞ Go to bed and wake up within the same 30-minute window every day, including weekends. This practice anchors your body’s circadian rhythm, providing a stable foundation for hormonal regulation.

- Optimize Your Sleep Environment ∞ Your bedroom should be completely dark, quiet, and cool. Blackout curtains, white noise machines, and lowering the thermostat can significantly improve sleep onset and quality.

- Implement a Pre-Sleep Wind-Down Routine ∞ An hour before bed, cease all work and screen time. The blue light from electronic devices suppresses melatonin production. Instead, engage in calming activities like reading a physical book, gentle stretching, or meditation.

- Time Your Light Exposure ∞ Expose yourself to bright, natural sunlight for at least 15-20 minutes as early as possible after waking. This powerful signal helps to lock in your circadian clock and reinforces the natural morning cortisol surge.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of sleep’s role in hormonal regulation requires moving beyond general principles to the specific mechanisms of sleep architecture and autonomic nervous system modulation. The nightly sleep period is a highly structured sequence of distinct stages, primarily categorized into Non-Rapid Eye Movement (NREM) sleep (which includes deep “slow-wave” sleep) and Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep.

The pulsatile release of specific hormones is tightly coupled to these distinct neurophysiological states. Therefore, interventions that improve sleep quality do so by optimizing the time spent in the most hormonally restorative stages.

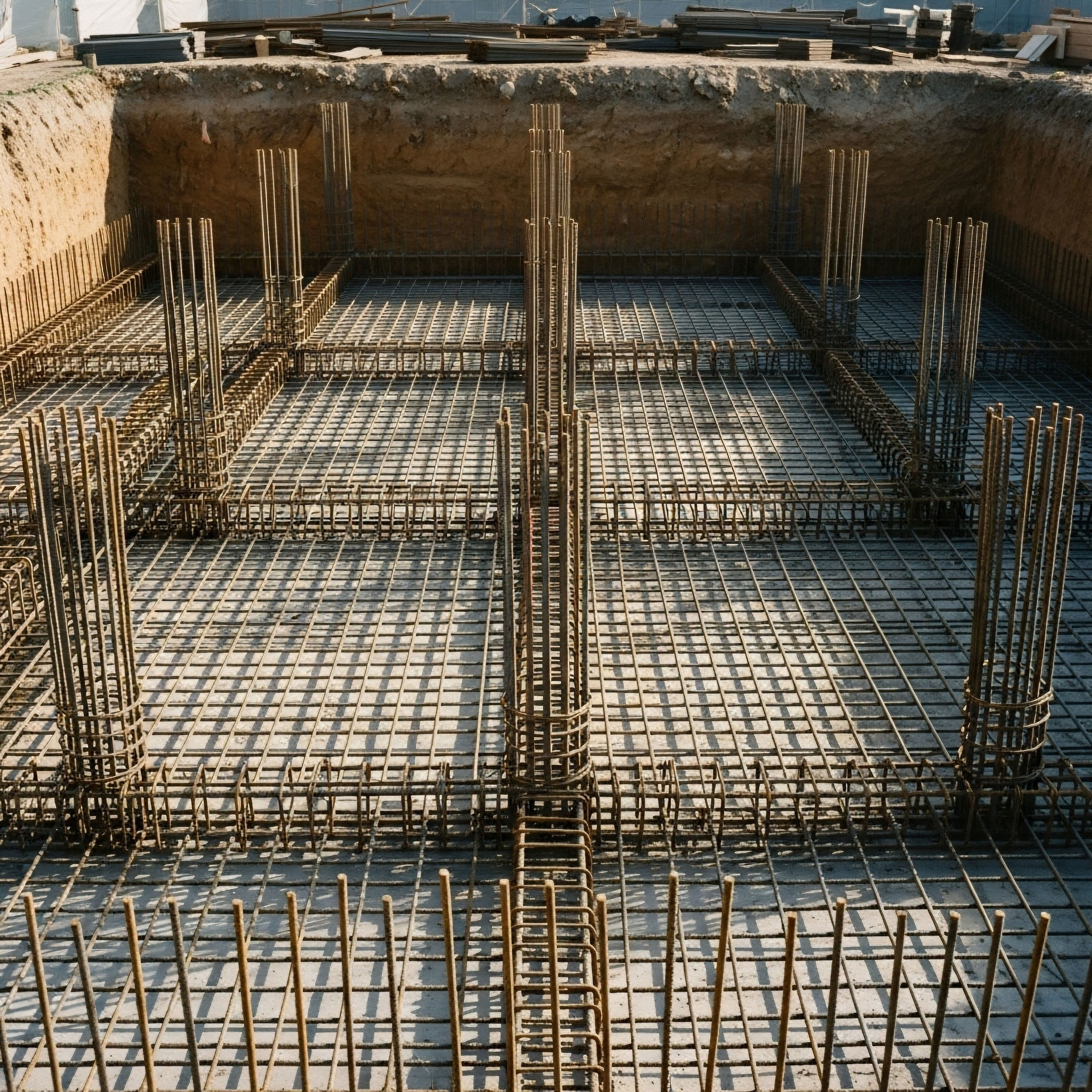

The most significant endocrine event of the night is the massive release of Growth Hormone (GH) from the anterior pituitary, which is almost exclusively linked to NREM slow-wave sleep. This is a period of high-amplitude, low-frequency delta wave activity in the brain, reflecting a state of deep neuronal synchrony.

It is this synchronized state that facilitates the powerful outflow of GH. Any fragmentation of sleep that prevents an individual from achieving and sustaining this deep stage directly truncates GH secretion. This has profound implications not just for athletes seeking muscle repair, but for the general adult population, as GH is a key modulator of body composition, metabolic function, and tissue integrity.

How Does the Autonomic Nervous System Mediate Sleep’s Hormonal Effects?

The autonomic nervous system (ANS), with its sympathetic (“fight-or-flight”) and parasympathetic (“rest-and-digest”) branches, is the conduit through which the brain’s sleep state influences peripheral endocrine glands. During NREM deep sleep, there is a profound shift toward parasympathetic dominance. This state is characterized by reduced heart rate, blood pressure, and sympathetic outflow.

This systemic calming is a prerequisite for optimal endocrine function. For instance, the parasympathetic tone enhances pancreatic beta-cell sensitivity, facilitating efficient insulin secretion and glucose regulation.

Conversely, sleep deprivation, or even sleep restriction to four or five hours per night, induces a state of heightened sympathovagal balance. The body remains in a state of elevated sympathetic nervous system activity, even during its limited rest period.

This chronic sympathetic drive directly promotes insulin resistance at the cellular level and contributes to the dysregulated evening cortisol profile seen in poor sleepers. It is a state of being physiologically “on alert” when one should be in a state of deep repair. This ANS imbalance is a core mechanism linking poor sleep to a host of downstream pathologies, including hypertension, obesity, and diabetes.

The architecture of your sleep, specifically the time spent in deep slow-wave stages, dictates the efficacy of your body’s hormonal repair and regeneration programs.

This mechanistic understanding illuminates the rationale behind certain therapeutic protocols. For example, Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy, using agents like Sermorelin or Ipamorelin/CJC-1295, is designed to mimic the natural signaling process that has been compromised by poor sleep. These peptides are secretagogues, meaning they stimulate the pituitary gland to release its own GH.

Their action is most effective when administered before sleep, as they augment the body’s natural, albeit diminished, slow-wave sleep-associated GH pulse. They are, in essence, a clinical intervention designed to restore a specific endocrine event that has been lost due to disruptions in sleep architecture.

- Thyroid Axis ∞ Sleep restriction has been shown to blunt the normal nocturnal rise in Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH). After several days of limited sleep, mean TSH levels can be reduced by over 30%, leading to a downregulation of the entire thyroid axis and contributing to symptoms of fatigue and slowed metabolism.

- Gonadotropins ∞ The pulsatile release of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus, which governs the release of Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH), is highly dependent on a consolidated sleep period. Disrupted sleep can alter the frequency and amplitude of these pulses, directly impacting testosterone production in men and ovulation in women.

- Neurotransmitter Function ∞ Sleep is also essential for recalibrating neurotransmitter systems, including dopamine and serotonin. Imbalances in these systems, driven by poor sleep, can affect mood and motivation, which are often comorbid with the physical symptoms of hormonal decline.

| Sleep Stage | Primary Neurological Characteristics | Key Hormonal Events |

|---|---|---|

| NREM Stage 1-2 (Light Sleep) |

Transition from wakefulness; slowing brain waves. |

Initiation of melatonin secretion; gradual decrease in cortisol. |

| NREM Stage 3 (Deep/Slow-Wave Sleep) |

High-amplitude, low-frequency delta waves; high neuronal synchrony. |

Peak release of Human Growth Hormone (GH); peak prolactin release; continued suppression of cortisol. |

| REM Sleep |

Active, desynchronized brain waves similar to wakefulness; muscle atonia. |

Cortisol secretion begins its circadian rise; modulation of testosterone release. |

The clinical implication is clear. Before initiating or optimizing any hormonal therapy, such as TRT for men or women, a thorough assessment of sleep quality is mandatory. An individual with severely disrupted sleep architecture will have a compromised physiological environment.

Their elevated sympathetic tone and insulin resistance may blunt the effectiveness of exogenous hormone therapy and may even exacerbate certain side effects. Therefore, a foundational intervention focused on improving sleep hygiene and restoring healthy sleep patterns is not an adjunctive therapy; it is a primary component of a successful and sustainable hormonal optimization protocol.

References

- Leproult, R. & Van Cauter, E. (2010). Role of sleep and sleep loss in hormonal release and metabolism. Endocrine development, 17, 11 ∞ 21.

- Spiegel, K. Tasali, E. Penev, P. & Van Cauter, E. (2004). Brief communication ∞ Sleep curtailment in healthy young men is associated with decreased leptin levels, elevated ghrelin levels, and increased hunger and appetite. Annals of internal medicine, 141(11), 846 ∞ 850.

- Knutson, K. L. Spiegel, K. Penev, P. & Van Cauter, E. (2007). The metabolic consequences of sleep deprivation. Sleep medicine reviews, 11(3), 163 ∞ 178.

- Kim, T. W. Jeong, J. H. & Hong, S. C. (2015). The impact of sleep and circadian disturbance on hormones and metabolism. International journal of endocrinology, 2015, 591729.

- Mullington, J. M. Haack, M. Toth, M. Serrador, J. M. & Meier-Ewert, H. K. (2009). Cardiovascular, inflammatory, and metabolic consequences of sleep deprivation. Progress in cardiovascular diseases, 51(4), 294 ∞ 302.

Reflection

A Personalized Path to Restoration

The information presented here offers a map of the intricate connections between your rest and your internal biochemistry. You have seen how the quality of your sleep is not a passive state but an active process of biological governance. The fatigue you may feel, the changes in your body, and the shifts in your mental clarity are not isolated symptoms.

They are data points, signals from a complex system communicating a need for recalibration. This knowledge transforms you from a passive recipient of symptoms into an active participant in your own health journey.

Consider your own daily rhythms. Think about the light you see in the morning, the food you consume, the stress you manage, and the environment in which you rest. Each of these is an input, a piece of information you are giving to your body’s regulatory systems.

The path to restoring your vitality begins with understanding these inputs and deliberately shaping them to support your biology. This is the foundation of personalized wellness. The journey is yours to direct, and the process of learning your own body’s language is the most empowering step you can take.

Glossary

endocrine system

circadian rhythm

sleep interventions

poor sleep

human growth hormone

sleep quality

hpa axis

insulin resistance

sleep deprivation

testosterone production

hpg axis

autonomic nervous system

sleep architecture

slow-wave sleep

growth hormone

nervous system