Fundamentals

You may have seen it on a blood test report, a simple acronym among a sea of others ∞ SHBG. For many, it is an unfamiliar term, easily overlooked. Yet, this single marker offers a profound glimpse into the intricate, silent conversations happening within your body.

Understanding Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin, or SHBG, is a foundational step in comprehending your own metabolic and hormonal health. It is a key piece of the puzzle, revealing how your systems are responding to the demands of your life, your diet, and your internal environment. Your body is constantly communicating with itself, and learning the language of these biomarkers is the first step toward reclaiming your vitality.

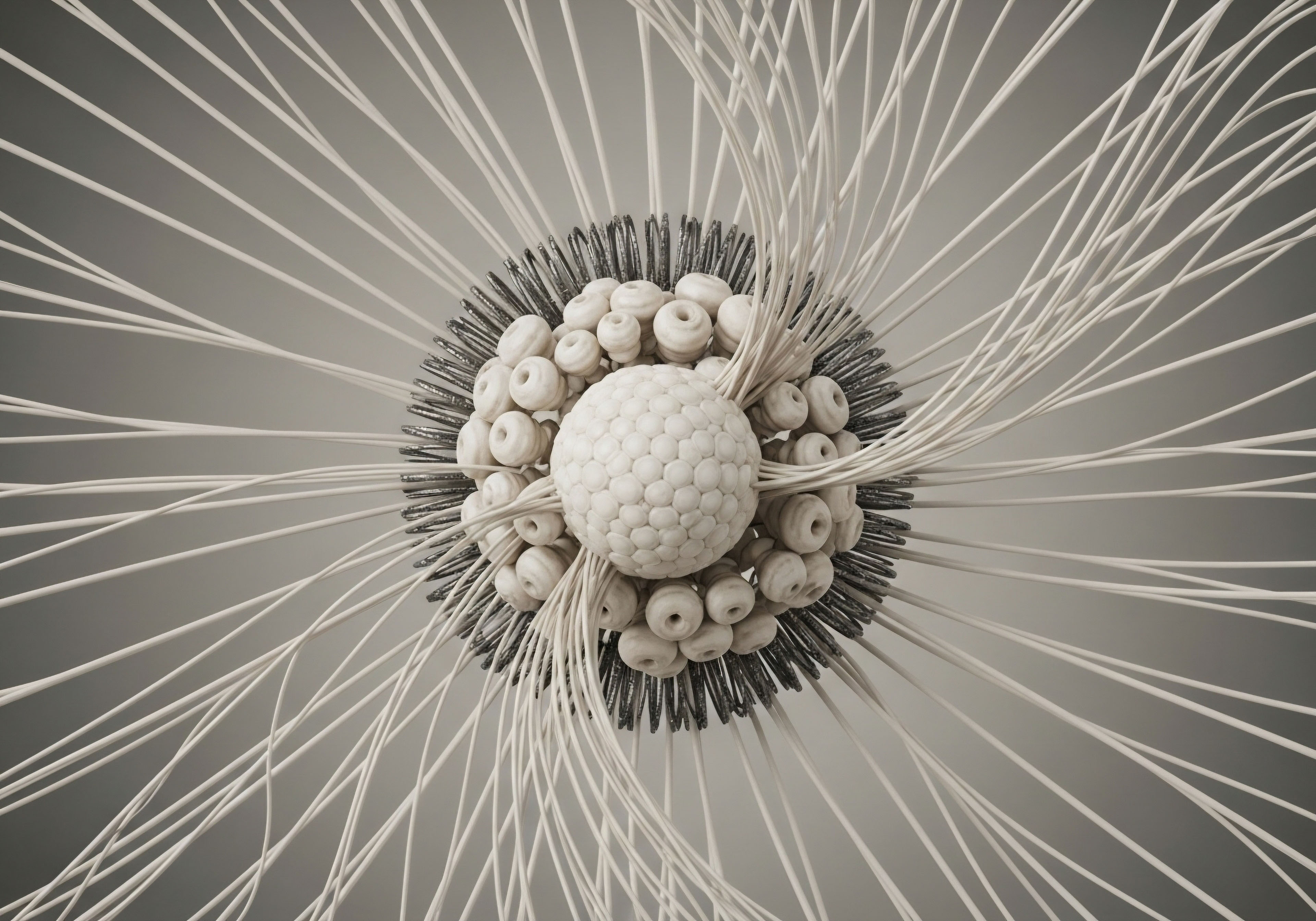

SHBG is a protein produced primarily by your liver. Its most well-understood role is to act as a transport vehicle for sex hormones, particularly testosterone and estradiol, through the bloodstream. Think of SHBG as a fleet of specialized shuttles. These shuttles bind to their hormonal passengers, rendering them inactive until they are released at specific target tissues.

The amount of available SHBG in your circulation directly dictates the quantity of “free” hormones ∞ those that are unbound and biologically active, ready to exert their effects on your cells. This regulation is a delicate balancing act, essential for maintaining physiological equilibrium.

The Cluster of Metabolic Dysregulation

Metabolic syndrome is a collection of conditions that occur together, collectively increasing your risk for significant health challenges, including cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. It is a state of systemic disharmony, where the body’s ability to manage energy and regulate core functions becomes compromised. Clinically, it is identified by the presence of several specific metabolic markers. Recognizing these signs is crucial, as they represent clear signals from your body that its internal processes are under strain.

To understand the connection with SHBG, we must first define the components of this syndrome. Each one tells a part of the story about your body’s metabolic state.

- Abdominal Obesity This refers to excess fat stored around the waistline. This visceral fat is metabolically active, producing inflammatory signals that disrupt normal bodily functions.

- High Triglycerides These are a type of fat found in your blood. Elevated levels indicate that your body may be struggling to clear fats from the bloodstream after meals, a process linked to how your body handles sugars and fats.

- Low HDL Cholesterol High-density lipoprotein, or HDL, is often called “good” cholesterol because it helps remove other forms of cholesterol from your bloodstream. Low levels suggest a reduced capacity for this vital cleanup process.

- High Blood Pressure This condition, also known as hypertension, reflects excessive force on the walls of your arteries. Over time, this sustained pressure can damage blood vessels and strain the heart.

- Elevated Fasting Glucose High levels of sugar in the blood after a period of not eating point toward the body’s declining ability to use insulin effectively, a state known as insulin resistance.

How Does SHBG Connect to Metabolic Health?

The relationship between SHBG and metabolic syndrome is one of profound clinical significance. Observational studies consistently show a strong inverse correlation ∞ as the features of metabolic syndrome worsen, SHBG levels tend to decline. An individual with low circulating SHBG is more likely to exhibit one or more of the five components of the syndrome.

This connection is so consistent that low SHBG is now considered a reliable biomarker for underlying metabolic dysfunction, often appearing even before conditions like type 2 diabetes are formally diagnosed.

A low level of SHBG is a strong and early indicator of underlying metabolic stress and insulin resistance.

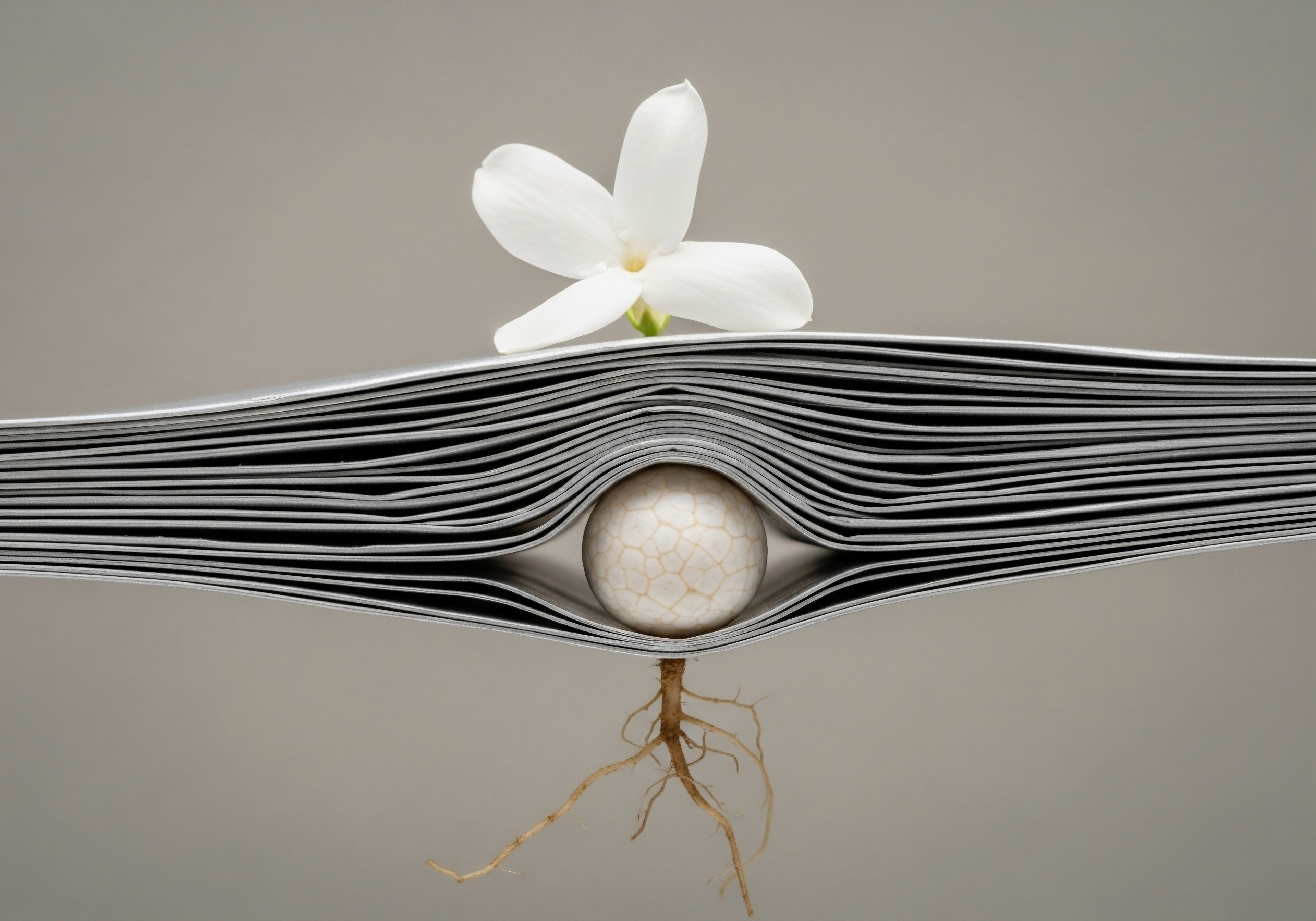

This relationship is not merely a statistical curiosity; it points to a deep physiological link between the liver, hormonal balance, and energy metabolism. The liver, as the producer of SHBG, is also the central hub for processing nutrients, glucose, and fats.

When the liver becomes burdened, particularly with excess fat accumulation due to conditions like insulin resistance, its functions are altered. One of the direct consequences of this hepatic stress is a reduction in its capacity to produce SHBG. Therefore, your SHBG level acts as a sensitive barometer, reflecting the health and operational status of your liver and your body’s overall metabolic efficiency.

Intermediate

To truly grasp the link between SHBG and metabolic risk, we must move beyond simple correlation and examine the biological mechanisms at play. The conversation begins in the liver, the body’s primary metabolic engine. It is here that SHBG is synthesized, and its production rate is exquisitely sensitive to the metabolic signals it receives.

The most powerful of these signals is insulin. In a state of health, insulin works efficiently to help your cells absorb glucose from the blood for energy. When insulin resistance develops, the cells become less responsive to its message. The pancreas compensates by producing even more insulin, leading to a condition of hyperinsulinemia, or chronically high insulin levels.

This excess insulin sends a direct message to the liver. One of its effects is to suppress the genetic expression of the SHBG gene. Specifically, hyperinsulinemia is thought to down-regulate a key transcription factor in the liver known as hepatocyte nuclear factor 4-alpha (HNF-4α).

HNF-4α is a master regulator that directly promotes the transcription of the SHBG gene. When its activity is dampened by the metabolic chaos of insulin resistance and associated liver fat accumulation, SHBG production falls. This creates a measurable drop in circulating SHBG levels, providing a direct window into the metabolic stress occurring within the liver.

The Free Hormone Conundrum

The reduction in SHBG has significant downstream effects on your endocrine system. With fewer SHBG “shuttles” available in the bloodstream, a larger proportion of sex hormones, like testosterone, exist in their “free” or unbound state. While this might initially sound beneficial, particularly for men concerned with testosterone levels, the reality is more complex.

The body’s tissues are calibrated to respond to a specific balance of free and bound hormones. An excess of free testosterone, driven by low SHBG, can be converted into estrogen at a higher rate in fat tissue, potentially disrupting the delicate testosterone-to-estrogen ratio critical for both male and female health.

This alteration in hormone bioavailability is a key part of the feedback loop that perpetuates metabolic syndrome. The hormonal imbalance can contribute further to fat storage, inflammation, and other metabolic disturbances. It is a systemic issue where a breakdown in one area ∞ glucose metabolism ∞ triggers a cascade of effects in another, such as hormonal signaling.

Chronically high insulin levels directly suppress the liver’s production of SHBG, altering the availability of active sex hormones.

Understanding this mechanism reframes SHBG from a passive transport molecule to an active participant in your metabolic story. Its level is a direct report on how well your liver is handling its metabolic load. For this reason, physicians and clinicians are increasingly using SHBG as a predictive biomarker.

A low SHBG level in a routine blood test can be an early warning sign, prompting a deeper investigation into insulin sensitivity and other metabolic markers, sometimes years before a patient meets the full criteria for metabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes.

What Factors Influence SHBG Levels?

Several physiological and lifestyle factors can influence your SHBG levels, highlighting the interconnectedness of your endocrine and metabolic systems. These factors work together to determine the final circulating concentration of this critical protein.

| Factor | Effect on SHBG | Underlying Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Insulin | Decreases | Suppresses the HNF-4α transcription factor in the liver, directly inhibiting SHBG gene expression. |

| Thyroid Hormone (T3) | Increases | Stimulates the promoter region of the SHBG gene in the liver, up-regulating its production. |

| Estrogen | Increases | Directly stimulates hepatic synthesis of SHBG, which is why women typically have higher levels than men. |

| Androgens (Testosterone) | Decreases | High levels of androgens send a negative feedback signal to the liver, reducing SHBG production. |

| High-Fiber Diet | Increases | Certain dietary patterns may improve insulin sensitivity and reduce liver fat, indirectly supporting SHBG synthesis. |

| Excess Caloric Intake | Decreases | Contributes to hepatic fat accumulation (steatosis) and insulin resistance, leading to SHBG suppression. |

This table illustrates that your SHBG level is a dynamic marker, responsive to a wide array of internal and external inputs. It sits at the crossroads of your hormonal status, your metabolic health, and even your dietary choices. Therefore, addressing a low SHBG level involves a holistic approach, focusing on the root cause, which is very often centered on improving insulin sensitivity and overall metabolic function.

Academic

The association between low serum SHBG and metabolic syndrome is robustly established through cross-sectional and prospective observational studies. A more sophisticated clinical question, however, pertains to causality. Does low SHBG directly contribute to the pathogenesis of metabolic dysfunction, or is it merely a passive biomarker reflecting underlying insulin resistance?

Advanced genetic research, particularly Mendelian randomization (MR) studies, has provided compelling data to address this question. MR analysis uses genetic variants, or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), associated with SHBG levels as an instrumental variable. Because these genetic variants are randomly allocated at conception, they allow researchers to assess the lifelong effect of lower or higher SHBG concentrations on disease risk without the confounding variables of lifestyle and environment.

Multiple MR studies have demonstrated that genetic variants predisposing individuals to lifelong lower SHBG levels are associated with a significantly higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes. This genetic evidence supports a causal role for SHBG in the pathophysiology of T2DM. The mechanism appears to be multifaceted.

While the free hormone hypothesis offers a partial explanation, another emerging concept is the function of SHBG as a hepatokine ∞ a protein secreted by the liver that has its own signaling functions on distant tissues. This expands the role of SHBG from a simple transporter to an active endocrine organ in its own right.

SHBG as a Direct Modulator of Insulin Sensitivity

The discovery of a specific membrane receptor for SHBG (SHBG-R) on various cell types suggests that the SHBG protein itself can initiate intracellular signaling cascades. When SHBG binds to this receptor, it can activate a G-protein-linked second messenger system, typically involving cyclic AMP (cAMP).

This signaling can modulate cellular processes independently of the hormones it carries. While research into the full scope of SHBG-R signaling is ongoing, it presents a plausible mechanism through which SHBG could directly influence insulin sensitivity in tissues like muscle and fat.

Genetic evidence from Mendelian randomization studies supports a causal contribution of low SHBG to the development of type 2 diabetes.

This concept reframes the clinical narrative. A low SHBG state, driven by hepatic insulin resistance, could then directly exacerbate insulin resistance in peripheral tissues through reduced SHBG-R signaling. This establishes a true vicious cycle, where metabolic dysfunction in the liver perpetuates and amplifies metabolic dysfunction throughout the body. The clinical implication is that restoring SHBG levels is a valid therapeutic goal, a way to break the cycle.

Can Therapeutic Interventions Modify SHBG?

Given the evidence, interventions that raise SHBG levels are of significant clinical interest. These interventions primarily target the root cause of SHBG suppression ∞ insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis. The Diabetes Prevention Program, a major clinical trial, showed that intensive lifestyle intervention (ILS) resulted in significant increases in SHBG levels compared to placebo or metformin treatment. This demonstrates that improvements in diet and exercise, leading to weight loss and enhanced insulin sensitivity, can directly reverse the suppression of SHBG production.

The following table summarizes key prospective studies that have solidified the predictive value of SHBG for metabolic disease and cardiovascular events.

| Study/Analysis | Population | Key Finding | Clinical Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ding et al. (Meta-analysis) | Men and Women | Demonstrated a strong, graded inverse relationship between SHBG levels and future risk of T2DM. | Established SHBG as a powerful, independent predictor of diabetes risk. |

| UK Biobank Study | Men and Women | Found that genetically predicted higher SHBG was associated with a lower risk of coronary heart disease (CHD). | Suggests a causal protective role of SHBG against cardiovascular disease. |

| Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) | High-Risk Adults | Intensive lifestyle changes led to increased SHBG levels, correlating with reduced diabetes risk. | Shows that SHBG is a modifiable biomarker and that interventions improving it are effective. |

| Simo et al. (Adolescents) | Adolescent Boys and Girls | Low SHBG was already associated with components of metabolic syndrome in adolescents. | Indicates that SHBG is a very early marker of metabolic dysfunction, present before adulthood. |

These studies, taken together, build a compelling case. SHBG is a central node in a complex network linking liver health, glucose metabolism, hormonal balance, and cardiovascular outcomes. Its measurement provides actionable clinical data, and its modulation through targeted lifestyle and therapeutic protocols represents a sophisticated strategy for mitigating metabolic risk.

- Genetic Predisposition Certain SNPs within the SHBG gene are directly associated with lower circulating levels of the protein and a higher lifetime risk for developing T2DM, independent of other risk factors.

- Hepatic Regulation The primary driver of low SHBG is insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis, which suppress the SHBG gene’s transcription via the HNF-4α pathway in the liver.

- Systemic Consequences The resulting low SHBG state contributes to an altered hormonal milieu (increased free hormones) and potentially impaired direct signaling via the SHBG receptor, further perpetuating a state of metabolic dysregulation.

References

- Simo, R. et al. “Sex hormone-binding globulin levels and metabolic syndrome and its features in adolescents.” Clinical Endocrinology, vol. 75, no. 3, 2011, pp. 344-50.

- Mohammadi, Maryam, et al. “The relationship between components of metabolic syndrome and plasma level of sex hormone-binding globulin.” Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, vol. 20, no. 5, 2015, pp. 479-84.

- Ding, Eric L. et al. “Sex hormone-binding globulin and risk of type 2 diabetes in women and men.” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 361, no. 12, 2009, pp. 1152-63.

- Wallace, I. R. et al. “Sex hormone binding globulin and insulin resistance.” Clinical Endocrinology, vol. 78, no. 3, 2013, pp. 321-9.

- Pugeat, Michel, et al. “Sex hormone-binding globulin gene expression and insulin resistance.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 95, no. 9, 2010, pp. 4338-45.

- Zhao, Shanshan, et al. “Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in Men and Women.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 107, no. 7, 2022, e2821-e2831.

- Mather, K. J. et al. “Circulating sex hormone binding globulin levels are modified with intensive lifestyle intervention, but their changes did not independently predict diabetes risk in the Diabetes Prevention Program.” BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care, vol. 8, no. 2, 2020, e001614.

- Simo, R. and C. Hernández. “Sex hormone-binding globulin ∞ a new and promising biomarker for the diagnosis and prediction of metabolic syndrome.” Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, vol. 32, no. 1, 2009, pp. 78-80.

Reflection

From Biomarker to Blueprint

The journey to understanding a single lab value like SHBG reveals a fundamental truth about human biology ∞ no system operates in isolation. Your hormonal health is inextricably linked to your metabolic function, and both are reflections of the constant dialogue between your genes, your lifestyle, and your environment.

The knowledge that a protein produced in your liver can so accurately predict the health of your cardiovascular system years down the line is a powerful realization. It transforms the way you see your body, shifting the perspective from a collection of separate parts to a single, integrated, and intelligent system.

This understanding is more than academic. It is the key to proactive and personalized wellness. When you see your SHBG level on a report, you can now recognize it as a message from your liver about its current state. It is a piece of actionable data, a starting point for a conversation with a knowledgeable clinician about your unique physiology.

This knowledge empowers you to move beyond simply reacting to symptoms and toward consciously shaping your long-term health. The path forward is one of calibration and optimization, using these precise biological insights as your guide.

Glossary

shbg

sex hormone-binding globulin

metabolic syndrome

insulin resistance

shbg levels

metabolic dysfunction

biomarker

your shbg level

chronically high insulin levels

shbg gene

hnf-4α

endocrine system

free testosterone

insulin sensitivity

mendelian randomization

hepatokine

diabetes prevention program