Fundamentals

You may feel a sense of confusion when it comes to progesterone. You might have noticed that a friend’s prescription is a cream, while yours is a capsule, and both are intended to address hormonal symptoms. This difference in delivery method is at the heart of a profound biological distinction in how your body receives and utilizes this essential signaling molecule.

The journey of progesterone into your system is determined by its route of administration, and the primary gatekeeper in this process is the liver. Understanding this organ’s role is the first step in comprehending why the method of delivery is a critical component of your personalized wellness protocol.

Your liver is the body’s master metabolic hub, a sophisticated processing plant that inspects, sorts, and transforms substances that enter your bloodstream. When you swallow a capsule of micronized progesterone, it is absorbed from your digestive tract and travels directly to the liver before it can enter general circulation.

This initial journey is known as the “hepatic first-pass effect.” During this process, the liver’s enzymes extensively metabolize, or chemically alter, the progesterone molecule. A significant portion is converted into different substances called metabolites. These metabolites are not inert byproducts; they are biologically active compounds with their own unique effects, particularly on the central nervous system.

The Two Primary Pathways a Matter of Destination

The route chosen for progesterone supplementation determines whether it engages with this first-pass effect or largely bypasses it. This choice creates two fundamentally different therapeutic outcomes, each with specific applications and benefits. Thinking about these pathways helps to clarify why your clinician recommends a specific form of progesterone tailored to your individual symptoms and health profile.

One path involves direct absorption into the systemic circulation, avoiding the initial, intensive metabolic conversion in the liver. The other path intentionally utilizes the liver’s metabolic machinery to generate a cascade of secondary compounds. Both approaches are valid and powerful when applied correctly.

- The Direct-to-System Route This category includes transdermal (creams or gels applied to the skin), vaginal (suppositories or creams), and injectable (intramuscular or subcutaneous) methods. When progesterone is absorbed through the skin or vaginal mucosa, or injected into muscle, it enters the capillary networks and flows into the general bloodstream. From there, it travels throughout the body and reaches target tissues, like the uterus, in its original, unaltered form. The liver will eventually metabolize this progesterone, but it does so gradually as the blood circulates, not all at once in a concentrated pass.

- The Liver-First Route This pathway is exclusive to oral progesterone. After absorption from the small intestine, the portal vein transports the progesterone directly to the liver. Here, it undergoes substantial enzymatic conversion before the remaining progesterone and its newly created metabolites are released into systemic circulation. This initial, high-concentration encounter with liver enzymes dramatically changes the profile of the hormonal signal your body receives.

Why the Liver’s First Pass Changes Everything

The central consequence of the oral route is that the liver transforms a large percentage of the progesterone dose into metabolites, most notably allopregnanolone and pregnanediol. This means that when you take an oral capsule, you are administering a precursor for these other active substances. Allopregnanolone, in particular, is a potent neurosteroid.

It interacts with GABA-A receptors in the brain, which are the same receptors targeted by anti-anxiety medications. This interaction produces a calming, sedative, and mood-stabilizing effect. Therefore, oral progesterone protocols are often designed to leverage this metabolic conversion to address symptoms like anxiety, irritability, and insomnia, which are common during perimenopause and menopause.

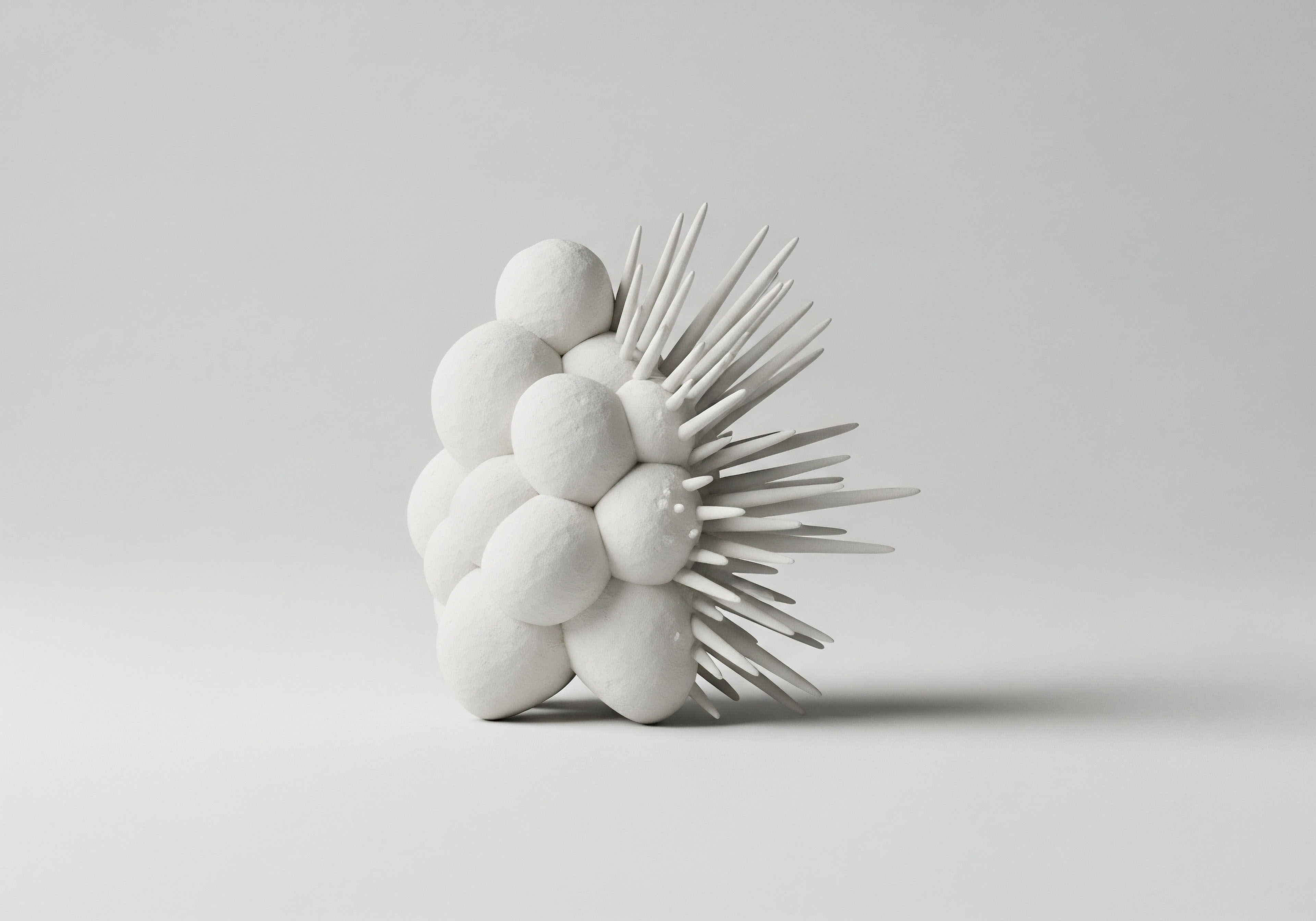

Oral progesterone’s journey through the liver transforms it, creating unique metabolites with their own distinct effects on the brain and nervous system.

Conversely, routes that bypass the liver deliver progesterone directly to the tissues where it is needed for its primary pro-gestational effects, such as balancing estrogen and supporting the uterine lining. Transdermal and vaginal applications are particularly effective for this purpose.

They provide a steady, consistent level of progesterone in the bloodstream without the large initial spike and subsequent surge of sedative metabolites seen with oral administration. This makes them suitable for individuals who require the direct hormonal effects of progesterone without the accompanying drowsiness, or for those whose livers may process medications less efficiently. The choice of administration is a strategic decision, made to align the biological action of the hormone with your specific therapeutic needs.

Intermediate

Advancing from a foundational knowledge of progesterone pathways requires a closer examination of the specific biochemical outcomes of each route. The decision to use oral versus non-oral progesterone is a clinical choice that hinges on pharmacokinetics ∞ the study of how a substance moves through the body, from absorption to elimination.

The liver’s first-pass metabolism of oral progesterone drastically alters its bioavailability and metabolic profile, creating a therapeutic tool with applications distinct from its non-orally administered counterparts. This section explores the “how” and “why” behind these differences, connecting them to tangible clinical goals and patient experiences.

Understanding Progesterone Metabolites the Neuroactive Cascade

When oral micronized progesterone enters the liver, it encounters a host of enzymes, primarily from the reductase family. These enzymes chemically reduce the progesterone molecule, leading to the formation of several metabolites. The two most clinically significant are allopregnanolone (a 5-alpha reduced metabolite) and pregnanolone (a 5-beta reduced metabolite). These are not merely breakdown products; they are potent neurosteroids that exert powerful effects on the central nervous system.

Allopregnanolone is a positive allosteric modulator of the GABA-A receptor. This means it binds to a site on the receptor that is different from the main binding site for the neurotransmitter GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid), but its presence enhances GABA’s natural calming effect.

When GABA binds to its receptor, it opens a chloride ion channel, allowing negatively charged chloride ions to flow into the neuron. This influx hyperpolarizes the cell, making it less likely to fire an electrical signal. Allopregnanolone makes this process more efficient, amplifying the brain’s primary inhibitory system.

This mechanism is responsible for the anxiolytic (anxiety-reducing), sedative, and even hypnotic (sleep-inducing) effects reported by many women who use oral progesterone. For a patient struggling with the anxiety, mood swings, and insomnia that often accompany hormonal fluctuations, this metabolic conversion is the primary therapeutic goal.

Comparing Administration Routes a Clinical Overview

Each method of progesterone delivery has a unique pharmacokinetic profile that dictates its clinical utility. Bypassing the liver’s first pass, as is the case with transdermal, vaginal, and injectable routes, results in higher systemic bioavailability of the parent progesterone molecule and a dramatically different ratio of progesterone to its metabolites. This distinction is critical for tailoring hormonal support to the individual’s needs.

The following table provides a comparative overview of the most common administration routes:

| Administration Route | Systemic Bioavailability | Primary Metabolite Profile | Typical Half-Life | Key Clinical Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral (Micronized) | Very low (<10%) | High levels of allopregnanolone and pregnanediol relative to progesterone. | Short (5-10 hours) | Addressing CNS symptoms like insomnia, anxiety, and mood instability. |

| Transdermal (Cream/Gel) | Variable; bypasses first-pass | Low levels of neuroactive metabolites; high progesterone-to-metabolite ratio. | Long (30-40 hours) | Providing steady, physiologic progesterone levels for systemic balance without sedation. |

| Vaginal (Suppository/Gel) | Moderate (4-8%) | Very low levels of neuroactive metabolites; high local uterine concentration. | Long (14-50 hours) | Targeting uterine tissue directly (first uterine pass effect) for endometrial support. |

| Intramuscular (Injection) | High (approaching 100%) | Minimal first-pass metabolites; achieves high, supraphysiologic progesterone levels. | Moderate (20-28 hours) | Luteal phase support in assisted reproductive technology (ART) or correcting significant deficiency. |

The Significance of Bioavailability and Half-Life

Oral progesterone’s very low bioavailability reflects the extensive hepatic metabolism it undergoes; much of the initial dose is converted to metabolites before it ever reaches systemic circulation. This is why oral doses are typically much higher (e.g. 100-200 mg) than those used in other methods. The short half-life necessitates daily, often bedtime, dosing to align its sedative effects with the natural sleep cycle.

Choosing a progesterone route is a strategic decision to either engage the liver for its neuroactive metabolites or bypass it for direct hormonal action.

Transdermal and vaginal routes provide a more sustained release. The skin and vaginal mucosa act as reservoirs, slowly releasing progesterone into the bloodstream over a longer period. This results in a longer half-life and more stable serum levels, mimicking the body’s natural luteal phase secretion more closely.

Intramuscular injections create a depot of progesterone in the muscle tissue, from which it is absorbed over time, leading to very high peak concentrations followed by a steady decline. This method is often reserved for specific clinical situations, like fertility treatments, where achieving high serum levels quickly is the priority.

Impact on Systemic Markers Lipids and SHBG

The liver is also responsible for synthesizing many important proteins and managing lipid metabolism. The route of hormone administration can influence these functions. Oral estrogens are known to increase levels of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) and can have a mixed effect on lipid profiles, sometimes increasing triglycerides.

When progesterone is administered orally alongside estrogen, it is processed by the liver in a similar manner. However, non-oral routes of progesterone, by bypassing the liver, have been shown to be neutral in their effect on lipid profiles and do not interfere with the beneficial effects of transdermal estrogen on HDL cholesterol.

This makes a combination of transdermal estrogen and a non-oral progesterone (like vaginal or transdermal) a preferred protocol for many individuals, particularly those with cardiovascular risk factors, as it separates the desired hormonal effects from unwanted hepatic interactions.

Academic

A sophisticated clinical application of progesterone therapy requires a molecular-level appreciation of its metabolic fate, which is overwhelmingly dictated by the route of administration. The differential impact of these routes on the liver extends beyond the generation of neurosteroids to influence systemic protein synthesis, lipid profiles, and inflammatory markers.

The choice between an oral or a parenteral (non-oral) route is a decision that modulates distinct enzymatic pathways, resulting in profoundly different pharmacodynamic effects. This section analyzes these differences from a systems-biology perspective, examining the enzymatic machinery, the downstream effects on biomarkers, and the clinical implications for personalized medicine.

Hepatic Enzymology the Metabolic Crossroads of Oral Progesterone

Upon entering the hepatic sinusoids following oral administration, progesterone becomes a substrate for a cascade of reductive enzymes. The primary transformations are mediated by two key enzyme families:

- 5α-Reductase and 5β-Reductase ∞ These enzymes catalyze the irreversible reduction of the double bond in the A-ring of the steroid nucleus. This is the rate-limiting step in the formation of dihydroprogesterone isomers. 5α-reductase (SRD5A) produces 5α-dihydroprogesterone (5α-DHP), while 5β-reductase (AKR1D1) produces 5β-dihydroprogesterone (5β-DHP). The expression and activity of these enzymes can vary significantly among individuals due to genetic polymorphisms, which partly explains the variable sedative response to oral progesterone.

- 3α-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase (3α-HSD) ∞ Following the initial reduction, the keto group at the C3 position is reduced by 3α-HSD enzymes (part of the aldo-keto reductase family). 5α-DHP is converted to allopregnanolone (3α,5α-tetrahydroprogesterone), and 5β-DHP is converted to pregnanolone (3α,5β-tetrahydroprogesterone). It is allopregnanolone that possesses the highest affinity for the GABA-A receptor, making it the most clinically relevant neurosteroid metabolite.

This entire sequence is what constitutes the hepatic first-pass metabolism. Parenteral routes such as transdermal, vaginal, and intramuscular administration deliver progesterone to the systemic circulation first. While progesterone circulating systemically will eventually be metabolized by the liver and in extra-hepatic tissues, it avoids this initial, high-concentration metabolic surge. Consequently, the ratio of parent progesterone to its 5α-reduced metabolites is dramatically higher with parenteral routes compared to the oral route.

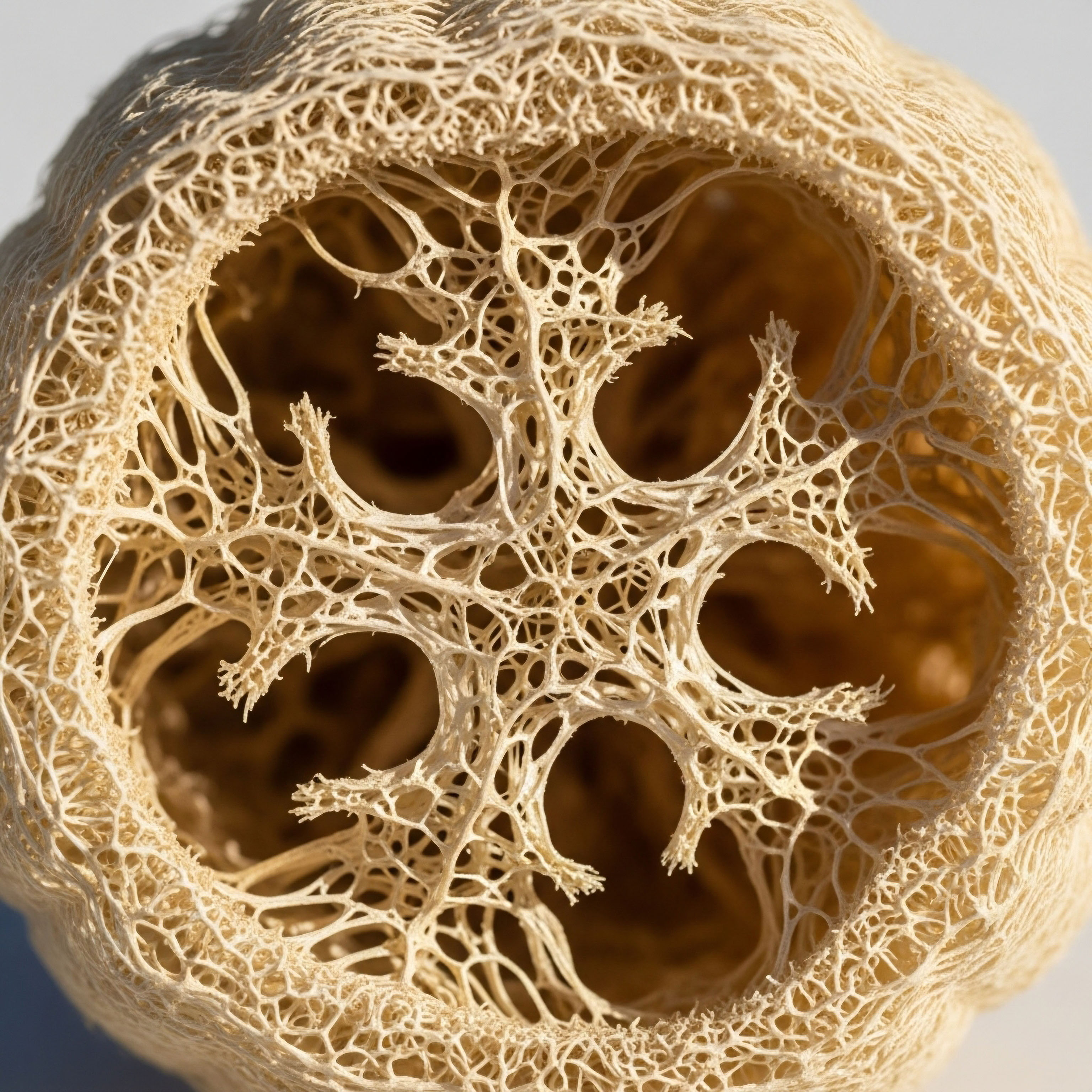

What Is the Uterine First Pass Effect?

Vaginal administration introduces another layer of complexity known as the “first uterine pass effect.” Progesterone absorbed through the vaginal mucosa can be transported directly to the adjacent uterine tissue through local vascular connections (the utero-vaginal venous plexus) before entering systemic circulation.

This results in significantly higher progesterone concentrations in the endometrial tissue compared to what would be expected from the observed serum levels. This mechanism makes vaginal progesterone exceptionally efficient for inducing secretory changes in the endometrium, a primary goal in hormone replacement therapy and fertility protocols, while minimizing systemic side effects like sedation.

Systemic Biomarker Modulation a Comparative Analysis

The liver’s role as a central regulator means that the route of progesterone administration can have measurable effects on various biomarkers beyond the hormone itself. These effects are primarily observed when progesterone is co-administered with estrogen in hormone therapy protocols. The following table details the differential impact on key metabolic and inflammatory markers.

| Biomarker | Impact of Oral Progesterone | Impact of Non-Oral Progesterone (Transdermal/Vaginal) | Clinical Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| HDL Cholesterol | Can sometimes blunt the HDL-increasing effect of oral estrogen. | Largely neutral; does not interfere with the beneficial HDL increase from transdermal estrogen. | Non-oral routes are preferred for preserving the cardioprotective lipid profile benefits of estrogen therapy. |

| Triglycerides | May have a neutral or slightly beneficial counterbalancing effect on estrogen-induced triglyceride elevation. | Neutral effect. Does not influence the triglyceride increases associated with oral estrogen. | The clinical significance is debated, but non-oral routes avoid complex hepatic lipid interactions. |

| Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) | Does not significantly alter SHBG levels. | Does not significantly alter SHBG levels. | Progesterone itself, regardless of route, has minimal impact on SHBG, unlike synthetic progestins which can have androgenic effects that lower SHBG. |

| C-Reactive Protein (CRP) | Oral progesterone may attenuate the increase in CRP sometimes seen with oral estrogen. | Transdermal progesterone, when combined with transdermal estrogen, is associated with no increase in CRP. | Avoiding hepatic inflammation is a key goal; the all-transdermal route appears most favorable in this regard. |

How Does Progesterone Route Influence Clinical Decision Making?

The data clearly indicate that the route of administration is a determining factor in the therapeutic outcome. For a postmenopausal woman with intact uterine tissue who is primarily experiencing vasomotor symptoms and sleep disturbances, a combination of transdermal estradiol and oral micronized progesterone at bedtime is a logical protocol.

This approach leverages transdermal estradiol for systemic symptom control while avoiding a hepatic first pass, and it utilizes oral progesterone’s first-pass metabolism to generate allopregnanolone for its sedative and anxiolytic benefits, while also providing endometrial protection.

The biochemical pathway of progesterone is a clinical choice, allowing for the precise targeting of either the uterine endometrium or the central nervous system.

Conversely, for a patient with a history of cardiovascular disease or concerns about lipid metabolism, a fully transdermal or vaginal approach is superior. A combination of transdermal estradiol and vaginal progesterone provides effective systemic hormone replacement and endometrial protection without the hepatic impact on lipids and inflammatory markers.

This demonstrates a sophisticated, systems-based approach to hormonal optimization, where the delivery route is selected to maximize therapeutic benefit and minimize potential risks by selectively engaging or bypassing the liver’s metabolic functions.

References

- de Lignières, B. L. Dennerstein, and P. F. Backstrom. “Influence of route of administration on progesterone metabolism.” Maturitas, vol. 21, no. 3, 1995, pp. 251-257.

- The Writing Group for the PEPI Trial. “Effects of estrogen or estrogen/progestin regimens on heart disease risk factors in postmenopausal women. The Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Trial.” JAMA, vol. 273, no. 3, 1995, pp. 199-208.

- Cicinelli, E. et al. “The ‘first uterine pass effect’ of progesterone administered by vaginal route.” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 68, no. 3, 1997, pp. 484-486.

- Söderpalm, A. H. V. et al. “Pharmacokinetics of progesterone and its metabolites allopregnanolone and pregnanolone after oral administration of low-dose progesterone.” Gynecological Endocrinology, vol. 21, no. 1, 2005, pp. 44-51.

- Stanczyk, F. Z. “All progestins are not created equal.” Steroids, vol. 68, no. 10-13, 2003, pp. 879-890.

- Freeman, E. W. et al. “Anxiolytic metabolites of progesterone ∞ correlation with mood and performance measures following oral progesterone administration to healthy female volunteers.” Neuroendocrinology, vol. 61, no. 2, 1995, pp. 202-209.

- Arafat, E. S. et al. “The pharmacokinetics of an intramuscular injection of progesterone.” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, vol. 159, no. 6, 1988, pp. 1460-1465.

- Kuhl, H. “Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens ∞ influence of different routes of administration.” Gynecological Endocrinology, vol. 8, suppl. 1, 2005, pp. 1-7.

Reflection

Calibrating Your Internal Systems

The information presented here provides a map of the biological pathways progesterone can take through your body. This is more than academic knowledge; it is the operating manual for a critical part of your internal communication network.

Seeing your body as an integrated system, where a single decision ∞ like the route of a hormone ∞ can create such distinct and predictable outcomes, is the first step toward a more empowered relationship with your own health. The journey through hormonal transition is a process of recalibration.

The feelings of anxiety, the sleepless nights, the changes in your cycle ∞ these are signals from a system in flux. Understanding that we have tools that can work with your body’s own metabolic processes, either to calm the nervous system via the liver or to directly support tissues by bypassing it, moves the conversation from one of managing decline to one of actively restoring function.

Your unique biochemistry and personal experience are the most important data points in this process. Consider this knowledge not as a final answer, but as the beginning of a more informed conversation with yourself and with a clinician who can help you interpret your body’s signals and choose the most precise tools to restore your vitality.