Fundamentals

You may feel a subtle shift, a change in your energy, your mood, or your body’s resilience that is difficult to articulate. These feelings are valid, representing real biological signals from your body’s intricate communication network. This network, the endocrine system, operates through chemical messengers called hormones.

Testosterone is one of these essential messengers, a foundational hormone for female physiology that is integral to maintaining vitality, cognitive sharpness, and a sense of well-being. Its role extends far beyond reproduction, influencing everything from the way your body manages energy to the clarity of your thoughts. Understanding its function is the first step toward deciphering your body’s signals and reclaiming your sense of self.

The conversation around testosterone biochemical recalibration is often framed by life stages, particularly the transition into menopause. This is because the ovaries, the primary producers of both estrogen and a significant portion of a woman’s testosterone, undergo a profound change.

Before menopause, during the reproductive years, the ovaries operate in a cyclical rhythm, guided by signals from the brain’s pituitary gland. This creates a dynamic hormonal environment. After menopause, ovarian production of these hormones ceases, creating a different, more stable, yet much lower, hormonal baseline. This biological shift is central to understanding why therapeutic guidelines for testosterone must be tailored to your specific life stage. The body’s needs and the underlying hormonal architecture are fundamentally different.

The body’s internal hormonal environment dictates the clinical approach to testosterone therapy, adapting from managing dynamic systems to restoring a stable foundation.

The Symphony of Your Hormones

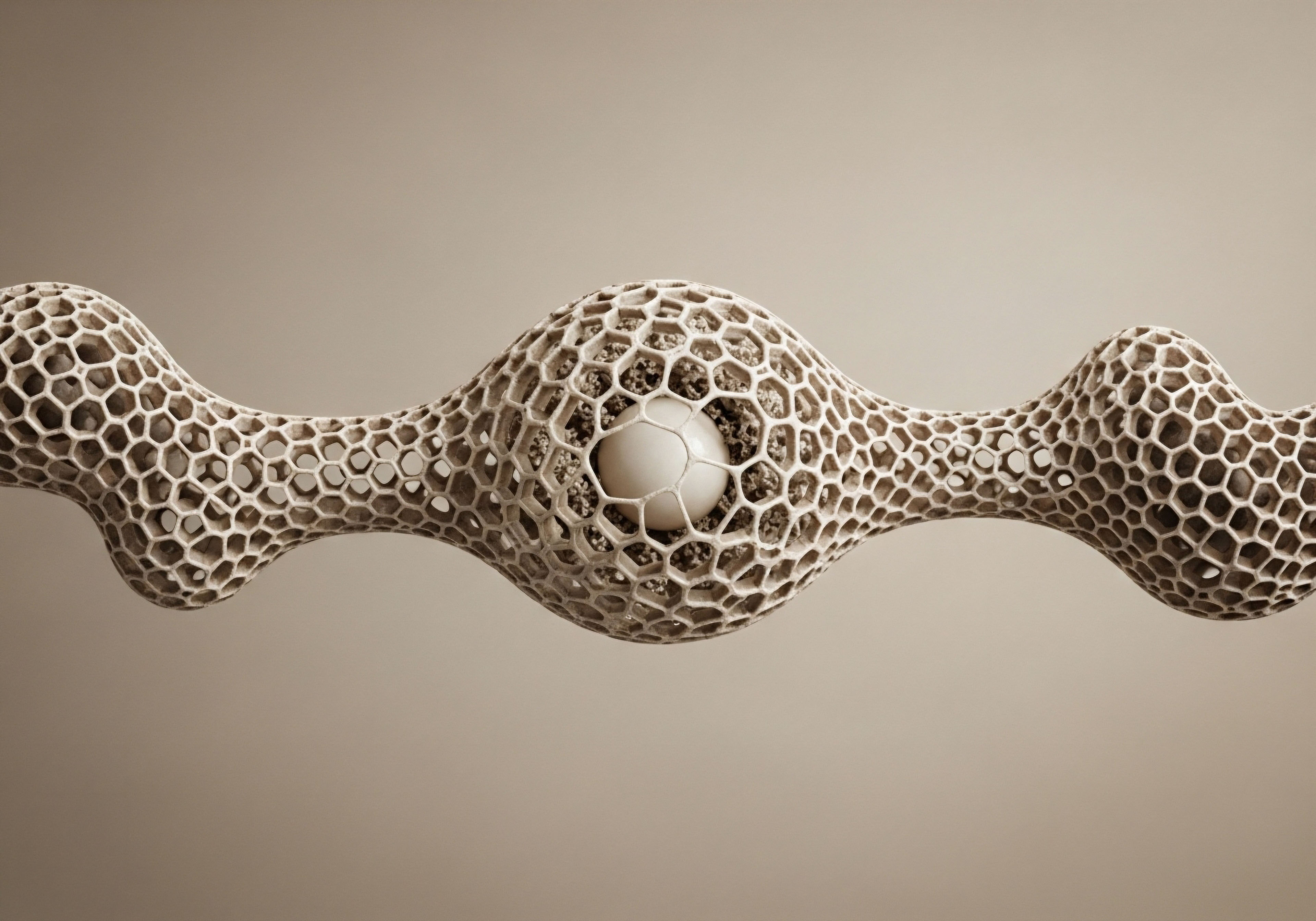

Think of your endocrine system as a finely tuned orchestra. In a premenopausal woman, the ovaries are the powerful conductor, directing the rhythmic rise and fall of estrogen and progesterone, while also contributing a steady baseline of testosterone. The adrenal glands, smaller but vital players, also produce androgens, including testosterone precursors.

The entire system is in constant communication, a complex feedback loop between the brain, ovaries, and adrenal glands known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. Every instrument plays its part in a coordinated performance that influences your monthly cycle, your mood, your energy, and your metabolic health.

In the postmenopausal phase, the conductor has left the stage. The ovaries no longer produce estrogen or significant amounts of testosterone. The music does not stop; instead, the orchestra reconfigures. The adrenal glands continue to produce androgens, which become the primary source of testosterone, and some of this testosterone is converted into estrogen in other body tissues, like fat cells.

The symphony becomes quieter, less dynamic, and plays a different tune. This new arrangement has profound implications for every system in the body, from bone density to cardiovascular health and cognitive function.

Testosterone’s Role in Female Physiology

Testosterone’s function in the female body is extensive and deeply integrated into overall health. Its presence is vital for maintaining a healthy and responsive system. It is not simply a libido hormone; its receptors are found in almost every tissue, including the brain, bone, muscle, and blood vessels, indicating its widespread importance.

- Musculoskeletal Health ∞ Testosterone plays a direct role in maintaining bone mineral density and promoting the growth and maintenance of lean muscle mass. This is critical for metabolic rate, strength, and preventing age-related frailty.

- Cognitive and Mood Function ∞ Within the brain, testosterone acts as a neurosteroid, influencing neurotransmitter systems that regulate mood, motivation, and cognitive functions like memory and spatial awareness. A healthy testosterone level contributes to a sense of assertiveness, confidence, and emotional resilience.

- Sexual Health ∞ Testosterone is a key driver of libido, or sexual desire. It also contributes to the physiological aspects of sexual response, such as sensitivity and arousal, by promoting healthy blood flow to genital tissues.

- Metabolic Wellbeing ∞ This hormone is a significant player in metabolic regulation. It helps improve insulin sensitivity, which allows your body to manage blood sugar more effectively. It also supports the body’s ability to use fat for energy, contributing to a healthier body composition.

What Changes with Time?

The decline in testosterone is a gradual process that often begins years before the final menstrual period. During the premenopausal and perimenopausal years, fluctuations in ovarian function can lead to an increasingly unpredictable hormonal environment. While estrogen levels may be erratic, testosterone levels often begin a slow, steady decline.

This can contribute to the very symptoms that are often dismissed as the normal stresses of life ∞ persistent fatigue, a slump in motivation, difficulty concentrating, and a noticeable drop in libido. Because the other hormones are still fluctuating, isolating the specific impact of declining testosterone can be challenging.

After menopause, the picture becomes clearer. With the cessation of ovarian function, testosterone levels fall to a new, stable, and significantly lower baseline. This drop, combined with the loss of estrogen, can accelerate changes in body composition, bone density, and sexual function. The symptoms of androgen insufficiency, once subtle, may become more pronounced.

It is this clearer clinical picture in the postmenopausal state that has allowed for more robust research and the development of specific therapeutic guidelines. The approach for a premenopausal woman, therefore, involves navigating a complex and dynamic system, while the approach for a postmenopausal woman focuses on restoring a foundational element that has been lost.

Intermediate

Moving beyond foundational concepts requires a clinical perspective on how testosterone protocols are differentiated between the premenopausal and postmenopausal states. The core distinction lies in the underlying physiology and, consequently, the evidence guiding therapeutic intervention. For a postmenopausal woman, the primary indication for testosterone therapy, as established by a global consensus of medical societies, is the diagnosis of Hypoactive Sexual Desire Dysfunction (HSDD).

This condition is characterized by a persistent and distressing lack of sexual desire. In this context, the goal of therapy is to restore testosterone to a physiological level that supports sexual health, with a body of evidence from randomized controlled trials confirming its efficacy and safety in the short term.

The clinical scenario for a premenopausal woman is substantially more complex. Her endocrine system remains dynamic, with cyclical hormonal fluctuations. Symptoms like low libido, fatigue, or mood changes can have multiple overlapping causes, including stress, relationship factors, other medical conditions, or the complex interplay of her own cycling hormones.

There is currently a lack of high-quality evidence from large-scale trials to support the general use of testosterone for any specific condition in premenopausal women. Consequently, its application is considered off-label and requires a highly individualized approach, a thorough evaluation to rule out other causes, and a deep understanding of the intricate hormonal balance at play.

The diagnostic process itself is more nuanced, as defining a “low” testosterone level is difficult when the numbers are meant to fluctuate.

A diagnosis of Hypoactive Sexual Desire Dysfunction is the primary evidence-based gateway for testosterone therapy in postmenopausal women, a clarity that is absent in the premenopausal context.

Diagnostic Approaches a Tale of Two Timelines

Diagnosing androgen insufficiency is a clinical skill that relies on a synthesis of patient-reported symptoms and biochemical analysis, with the emphasis shifting depending on menopausal status.

The Postmenopausal Assessment

In a postmenopausal woman, the diagnosis of HSDD is the central pillar. The 2019 Global Consensus Position Statement explicitly advises against using a blood testosterone level alone to diagnose HSDD. The diagnosis is clinical, based on a careful history that confirms a significant and bothersome loss of libido that is causing personal distress.

Laboratory testing is used as a baseline measurement before initiating therapy and for subsequent monitoring to ensure levels remain within a safe, physiological range. The goal is to replicate the testosterone levels of a healthy young woman, not to exceed them.

The Premenopausal Investigation

For a premenopausal woman presenting with symptoms, the investigation is broader. The clinician’s first responsibility is to conduct a comprehensive evaluation to exclude other potential causes. This includes:

- Psychosocial Factors ∞ Assessing relationship satisfaction, stress levels, and mental health is paramount, as these are potent modulators of libido and well-being.

- Medical Conditions ∞ Conditions like thyroid dysfunction, anemia, or depression can mimic symptoms of androgen insufficiency and must be ruled out.

- Medication Review ∞ Certain medications, including some hormonal contraceptives and antidepressants, can impact libido and hormone levels.

Only after this thorough workup might a clinician consider androgen insufficiency. Measuring total and free testosterone can be part of this evaluation, but interpretation is challenging. “Normal” ranges are wide and vary throughout the menstrual cycle. A low reading might be transient or may not correlate with symptoms. Therefore, the decision to trial therapy is based on a compelling clinical picture in the absence of other explanations, and it proceeds with significant caution.

Contrasting Treatment Protocols and Goals

The objectives and methods of hormonal optimization protocols differ significantly based on whether a woman is pre- or postmenopausal, reflecting the differences in both the evidence base and the underlying biological state.

The following table outlines the key distinctions in the hormonal landscape between these two phases of life, providing context for the different therapeutic strategies.

| Hormonal Factor | Typical Premenopausal State | Typical Postmenopausal State |

|---|---|---|

| Estrogen |

High and cyclical, produced primarily by the ovaries. |

Very low, no longer produced by ovaries; derived from peripheral conversion of androgens. |

| Progesterone |

Produced cyclically by the ovaries after ovulation. |

Essentially absent, unless supplemented via hormonal therapy. |

| Testosterone Source |

Approximately 25% from ovaries, 25% from adrenal glands, 50% from peripheral conversion of precursors. |

Primarily from adrenal glands and peripheral conversion; ovarian production ceases. |

| HPG Axis |

Active and dynamic, with regular feedback loops governing the menstrual cycle. |

Altered feedback loop; high levels of FSH and LH from the pituitary with no ovarian response. |

The treatment goals and monitoring strategies are tailored to these distinct physiological backdrops. The following table compares the clinical approaches.

| Treatment Aspect | Premenopausal Protocol Considerations | Postmenopausal Protocol Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Indication |

No established indication; considered off-label for persistent, unexplained symptoms after a thorough workup. |

Diagnosed Hypoactive Sexual Desire Dysfunction (HSDD) causing distress. |

| Evidence Base |

Limited; based on small studies and clinical experience. Long-term safety data is lacking. |

Supported by multiple randomized controlled trials and a Global Consensus Statement for HSDD. |

| Dosage Strategy |

Use of very low, cautious doses (e.g. 10-20 units weekly of Testosterone Cypionate 200mg/ml via subcutaneous injection). The goal is to gently supplement without disrupting the existing cyclical system. |

Dosing aims to restore testosterone to the normal physiological range for a healthy premenopausal woman. This may involve subcutaneous injections or pellet therapy. |

| Monitoring |

Frequent and careful monitoring of both symptoms and hormone levels to avoid supraphysiological concentrations and potential side effects. |

Initial baseline testing followed by regular monitoring (e.g. at 3, 6, and 12 months) to ensure levels remain within the target therapeutic window and to assess for side effects. |

| Concurrent Hormones |

Progesterone may be used to regulate cycles if needed, but the interaction with existing hormones is a key consideration. |

Often co-administered with systemic estrogen and progesterone therapy (in women with a uterus) to manage other menopausal symptoms. |

What Are the Safety Considerations?

For postmenopausal women, short-term studies using physiological doses of testosterone have shown a good safety profile. The most common side effects are mild and may include acne or a slight increase in facial hair. Virilizing effects like voice deepening or clitoromegaly are not seen with appropriate, monitored dosing. Long-term data on cardiovascular health and breast cancer risk are still being gathered, which is why ongoing monitoring and adherence to established guidelines are so important.

For premenopausal women, the safety considerations are magnified by the lack of long-term data. The primary concern is the potential for unintended consequences within a still-functioning, complex endocrine system. Exogenous testosterone could potentially disrupt the natural menstrual cycle or have other unforeseen effects.

This uncertainty is why the clinical community approaches testosterone use in this population with such a high degree of caution, reserving it for specific cases where the potential benefits are judged to outweigh the unknowns, and always with diligent follow-up.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of testosterone protocols across the female lifespan necessitates a systems-biology perspective, focusing on the progressive dysregulation and eventual recalibration of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal-Adrenal (HPGA) axis. The distinction between pre- and postmenopausal guidelines is a direct consequence of the differing states of this axis.

In the premenopausal woman, the system is characterized by its integrated, cyclical functionality. In the postmenopausal woman, the system operates from a new, non-cyclical, and androgen-dominant baseline established after ovarian senescence. Therapeutic interventions must respect this fundamental divergence in operating logic.

The primary challenge in the premenopausal period is diagnostic precision. Androgen insufficiency symptoms are nonspecific and overlap with numerous other conditions. Furthermore, the standard laboratory assays for testosterone often lack the sensitivity and precision to be reliable in the low concentrations typical of women, making the definition of “deficiency” a moving target.

The Endocrine Society’s clinical practice guidelines have highlighted this limitation, complicating the establishment of a clear biochemical threshold for intervention. Therefore, any premenopausal protocol is inherently experimental and must be predicated on a rigorous exclusion of all other etiologies and a deep appreciation for the potential to disrupt the delicate HPG feedback loops that govern fertility and menstrual regularity.

The shift from pre- to postmenopausal testosterone therapy reflects a strategic change from cautiously modulating a dynamic, integrated hormonal axis to methodically restoring a key component of a system that has reached a new, stable state.

The HPGA Axis from Fluctuation to Stability

The HPGA axis is the master control system of reproductive and much of metabolic endocrinology. In premenopausal women, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus stimulates the pituitary to release luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). These gonadotropins act on the ovaries, driving folliculogenesis and the production of estradiol and progesterone in a cyclical pattern.

LH also stimulates ovarian theca cells to produce androgens, including androstenedione and testosterone, which serve as both active hormones and precursors for estrogen synthesis via the aromatase enzyme.

Perimenopause marks the beginning of axis dysregulation. As the ovarian follicular pool depletes, feedback signals become erratic. FSH levels begin to rise in an attempt to stimulate a less responsive ovary. This phase is characterized by hormonal chaos. Following the final menstrual period, ovarian senescence is complete.

The ovaries cease to respond to gonadotropins and no longer produce significant estradiol or testosterone. The HPG axis finds a new equilibrium ∞ GnRH, FSH, and LH levels are persistently high due to the loss of negative feedback from ovarian hormones.

The adrenal glands, under the influence of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, become the principal source of androgens, primarily dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and androstenedione, which are converted to testosterone in peripheral tissues. This postmenopausal state is one of relative androgen predominance, even though the absolute levels of androgens are lower than in youth.

Molecular Actions and Therapeutic Targets

Testosterone exerts its effects through several mechanisms. It can bind directly to androgen receptors (AR) to modulate gene transcription. It can also be converted by the 5-alpha reductase enzyme to dihydrotestosterone (DHT), a more potent AR agonist. Finally, it can be converted by the aromatase enzyme to estradiol, which then acts on estrogen receptors (ER).

This metabolic plasticity means that administering testosterone can have both androgenic and estrogenic effects, the balance of which depends on the activity of these enzymes in target tissues like the brain, bone, and adipose tissue.

In postmenopausal women with HSDD, the therapeutic goal is to restore AR signaling in key areas of the brain associated with sexual desire, while also potentially increasing local estradiol production. The Global Consensus Position Statement, based on a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, confirms that achieving physiological testosterone levels effectively improves sexual desire, arousal, and overall sexual satisfaction. The evidence strongly supports this specific therapeutic target.

In premenopausal women, the targets are less clear. If a woman is experiencing low libido due to an SSRI antidepressant, for example, the mechanism may involve serotonin’s inhibitory effects on dopamine and norepinephrine pathways, which are modulated by androgens. A cautious trial of testosterone might aim to counteract this effect.

However, this is a complex neurochemical intervention with potential downstream consequences on the HPG axis. This highlights why such an approach remains outside mainstream guidelines and is the domain of specialized clinical practice.

Pharmacokinetic Considerations a Point of Digression

The method of testosterone delivery is a critical variable that influences clinical outcomes, a point of particular importance when translating academic understanding to practical application. The choice of delivery system determines the pharmacokinetics of the hormone ∞ its absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion.

In my clinical experience, aligning the delivery system with the patient’s physiology and therapeutic goals is fundamental. Intramuscular injections of Testosterone Cypionate, for example, create a peak level followed by a trough, a pattern that can be managed with weekly or bi-weekly dosing to maintain stability.

Subcutaneous pellet therapy, conversely, provides a very stable, long-term release of testosterone over several months, which can be ideal for postmenopausal women seeking consistent restoration. Transdermal creams offer daily application but can have variable absorption and risk of transference to others. The selection of a protocol is a decision about which pharmacokinetic profile best serves the biological context, whether that is the stable deficiency of postmenopause or the delicate, fluctuating system of premenopause.

Why Is Long-Term Data so Important?

The endocrine system is characterized by its long-term influence on chronic disease risk. Hormones modulate cardiovascular health, bone metabolism, and cellular proliferation over decades. The current evidence for testosterone therapy in women is primarily from studies lasting two years or less. While these trials provide reassurance about short-term safety, particularly regarding virilization and metabolic markers, they are insufficient to definitively assess long-term risks, especially concerning breast cancer and cardiovascular events.

For postmenopausal women, who may be on therapy for many years, this data gap is significant. The current consensus is that physiological testosterone replacement does not appear to increase breast density or breast cancer risk in the short term, and may even be protective, but longer-term studies are needed for a conclusive statement.

For premenopausal women, the data gap is even wider. The lack of any long-term studies makes prescribing a matter of careful clinical judgment and extensive patient counseling about the unknown risks. This evidentiary disparity is the single greatest factor differentiating the academic and clinical confidence in postmenopausal versus premenopausal testosterone protocols.

References

- Davis, Susan R. et al. “Global Consensus Position Statement on the Use of Testosterone Therapy for Women.” Climacteric, vol. 22, no. 5, 2019, pp. 429-434.

- Davis, Susan R. et al. “Global Consensus Position Statement on the Use of Testosterone Therapy for Women.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 104, no. 10, 2019, pp. 4660-4666.

- Glaser, Rebecca, and Constantine Dimitrakakis. “Testosterone therapy in women ∞ myths and misconceptions.” Maturitas, vol. 74, no. 3, 2013, pp. 230-4.

- Fonseca, Helena Proni, et al. “Androgen deficiency in women.” Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira, vol. 56, no. 5, 2010, pp. 579-82.

- Mathur, Ruchi, and Glenn D. Braunstein. “Androgen deficiency and therapy in women.” Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Obesity, vol. 17, no. 4, 2010, pp. 342-9.

- Bachmann, Gloria, et al. “Female androgen insufficiency ∞ the Princeton consensus statement on definition and classification.” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 77, no. 4, 2002, pp. 660-665.

- Traish, Abdulmaged M. et al. “The dark side of testosterone deficiency ∞ I. Metabolic syndrome and erectile dysfunction.” Journal of Andrology, vol. 30, no. 1, 2009, pp. 10-22.

Reflection

Charting Your Own Biological Course

You have now explored the intricate biological logic that shapes the clinical application of testosterone in women. You have seen how the body’s internal architecture shifts over a lifetime, and why a therapeutic approach must honor that evolution. This knowledge is more than a collection of facts; it is a set of tools for self-understanding.

It allows you to listen to your body with greater clarity and to ask more precise questions. The journey toward optimal function is deeply personal. The feelings and symptoms you experience are the starting point of a vital investigation into your own unique physiology.

Understanding the difference between a premenopausal and postmenopausal state is understanding the difference between a system in dynamic flux and one that has settled into a new baseline. Which state more closely resembles your own? What signals is your body sending about its current operational capacity?

This information serves as a map, but you are the navigator of your own health journey. The path forward involves taking this foundational knowledge and using it to engage in a productive, informed dialogue with a clinical partner who can help you interpret your unique biological blueprint and co-create a strategy for lifelong vitality.