Fundamentals

The experience of a struggling thyroid system is deeply personal and pervasive. It manifests as a persistent chill that blankets the body, a cognitive fog that obscures sharp thought, and a profound fatigue that sleep cannot seem to remedy. You may feel this deep in your bones, a sense of your internal furnace dwindling to embers.

When you seek answers, the clinical process often translates these lived experiences into a series of numbers on a lab report. This is the starting point of a journey toward understanding the intricate biological conversations that govern your energy, metabolism, and vitality.

The conventional approach to addressing low thyroid function is built upon a principle of direct, reliable replacement. This therapeutic model identifies a deficiency and provides the missing element. Levothyroxine, a synthetic form of the thyroid hormone thyroxine (T4), is the cornerstone of this strategy.

It is a bioidentical molecule that replenishes the body’s primary reservoir of thyroid hormone. The objective is to restore hormonal balance in the bloodstream, which is typically monitored by measuring Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH). TSH is the signal sent from the pituitary gland to the thyroid; when T4 levels are low, TSH rises, calling for more production.

By providing sufficient T4, the TSH level typically returns to a normal range, indicating to the clinical observer that the hormonal feedback loop is satisfied.

A Different Operational Philosophy

Peptide therapies function from an entirely different operational standpoint. They are designed to engage in systemic communication rather than direct replacement. These therapies utilize small protein chains, known as peptides, that act as precise signaling molecules. In the context of thyroid health, specific peptides can interact directly with the control centers in the brain.

For instance, analogs of Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone (TRH) are peptides that communicate with the pituitary gland. Their function is to prompt the pituitary to produce and release its own TSH, thereby engaging the body’s innate capacity to manage the thyroid gland. This method seeks to restore the natural, pulsatile rhythm of hormonal conversation within the body’s sophisticated endocrine architecture.

Conventional therapy replaces the final hormone product, while peptide therapy aims to restore the upstream signaling that directs its production.

The Body’s Metabolic Command Center

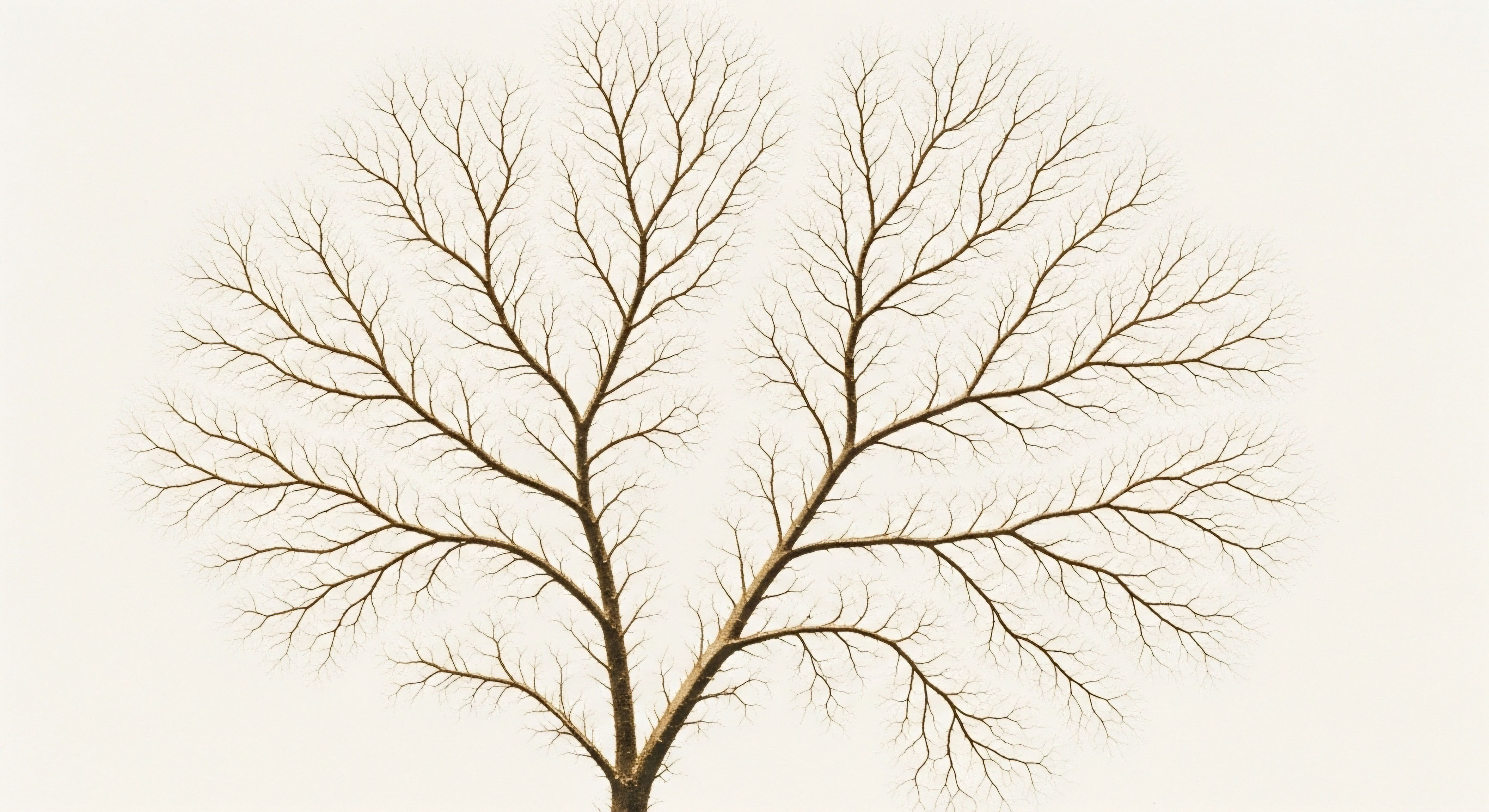

To grasp the distinction between these two approaches, one must first appreciate the biological system they influence ∞ the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) axis. This is the body’s central command structure for regulating metabolism. The process is an elegant cascade of communication:

- The Hypothalamus ∞ Located in the brain, it senses the body’s metabolic needs and releases Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone (TRH).

- The Pituitary Gland ∞ Receiving the TRH signal, this master gland responds by secreting Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH) into the bloodstream.

- The Thyroid Gland ∞ TSH travels to the thyroid gland in the neck, instructing it to produce and release its hormones, primarily the storage hormone T4 and the active hormone T3.

Conventional T4 therapy adds to the final step of this cascade, supplying the hormone that the thyroid gland itself is failing to produce in sufficient quantity. Peptide therapies, conversely, intervene at the top of the cascade, seeking to repair and amplify the initial signals from the brain. This foundational difference in mechanism defines the unique potential and application of each approach on the path to restoring metabolic wellness.

Intermediate

Advancing beyond foundational concepts requires a more detailed examination of the clinical tools themselves. Understanding how each therapeutic modality interacts with the body’s intricate physiology illuminates its specific applications, strengths, and limitations. This involves appreciating the subtle yet significant differences between hormone replacement and hormone regulation, and recognizing how the body’s broader systemic state can influence the outcome of any intervention.

The Mechanics of Conventional Thyroid Protocols

Conventional treatment for hypothyroidism is a well-established science focused on restoring and maintaining a euthyroid state, a condition of normal thyroid function, primarily through monitoring serum hormone levels. The tools for this are precise and have been refined over decades of clinical use.

Levothyroxine T4 Monotherapy

Levothyroxine is a prohormone, meaning it is a precursor to the more biologically active hormone. After ingestion, it is absorbed and circulates throughout the body as T4. For it to exert its metabolic effects, it must be converted into triiodothyronine (T3) within the body’s cells, a process carried out by enzymes called deiodinases.

This conversion is a critical step that happens in various tissues, including the liver, kidneys, and brain. The entire strategy rests on the body’s ability to perform this conversion efficiently. Clinical management involves regular blood tests to ensure the dose of levothyroxine is sufficient to keep TSH within the desired therapeutic range, typically between 0.4 and 4.0 mIU/L. This approach is effective for a majority of individuals with primary hypothyroidism, where the thyroid gland itself is the source of the problem.

The Question of Combination Therapy T4 and T3

A subset of individuals continues to experience hypothyroid symptoms despite having normal TSH levels on levothyroxine monotherapy. One physiological explanation is inefficient conversion of T4 to the active T3. For these individuals, combination therapy, which involves adding a direct dose of T3 (Liothyronine), may be considered.

Liothyronine provides the active hormone directly, bypassing the need for conversion. This can produce a more immediate effect on cellular metabolism. However, its management is more complex due to its shorter half-life and more potent activity, which can increase the risk of side effects if not dosed carefully.

| Hormone | Mechanism of Action | Biological Half-Life | Primary Clinical Application | Monitoring Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levothyroxine (T4) | Synthetic prohormone; requires enzymatic conversion to active T3 in peripheral tissues. | Approximately 7 days | Standard first-line treatment for hypothyroidism. | Serum TSH levels. |

| Liothyronine (T3) | Synthetic active hormone; directly binds to nuclear receptors in cells. | Approximately 1 day | Used in combination therapy for poor converters or for specific diagnostic tests. | Serum T3 levels and clinical symptoms. |

The Mechanics of Peptide Based Protocols

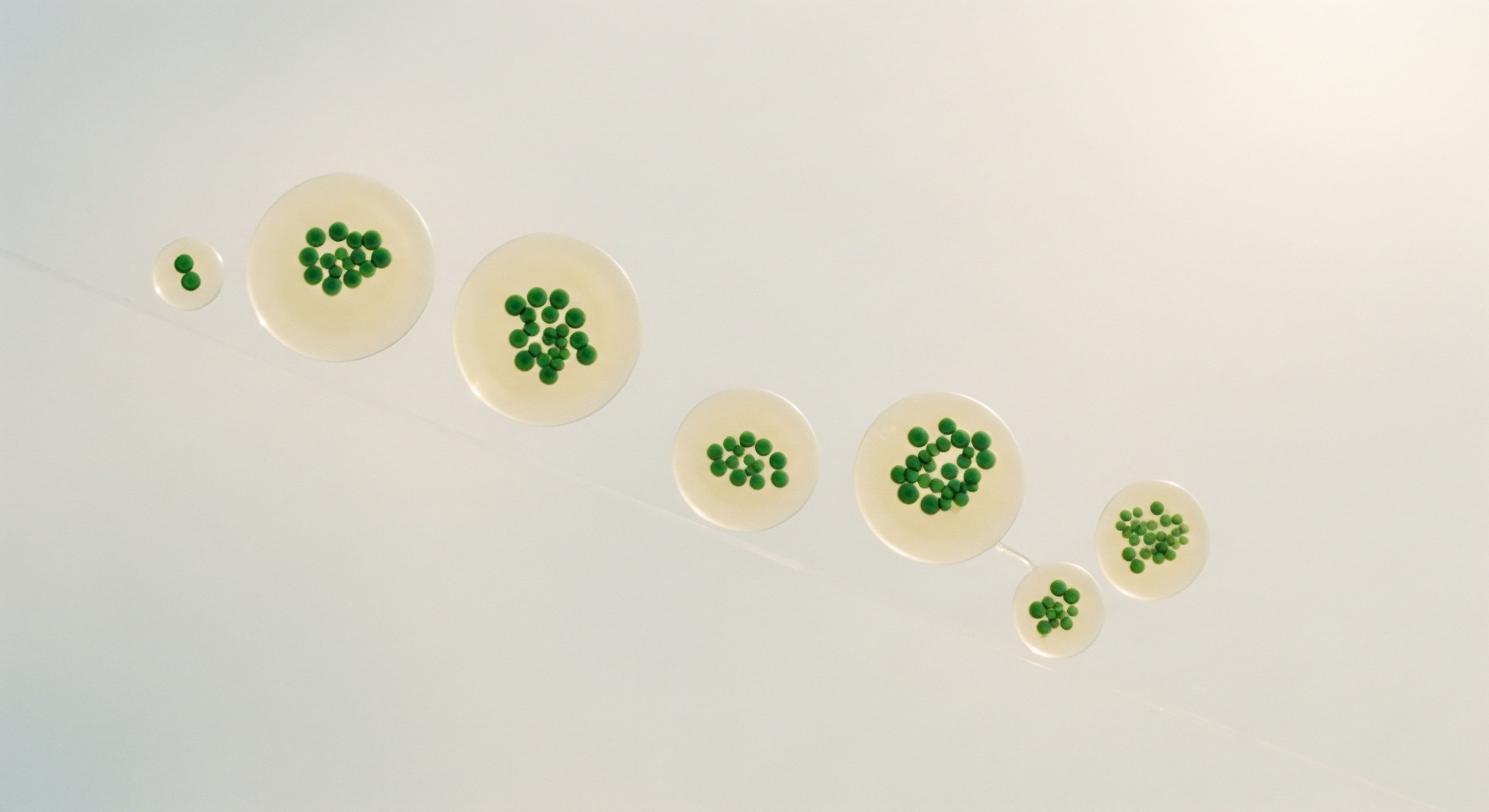

Peptide therapies represent a shift in strategy from hormone replacement to physiological stimulation. The goal is to encourage the body’s own endocrine glands to function more effectively by providing precise, targeted signals. This approach is inherently more dynamic, as it relies on the integrity of the existing biological machinery.

TRH Analogs a Signal from the Top

The primary peptide strategy for thyroid function involves the use of Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone (TRH) or its synthetic analogs. Protirelin is a synthetic version of TRH. When administered, it travels to the anterior pituitary and directly stimulates the thyrotroph cells to synthesize and release TSH.

This action preserves the natural pulsatile release of TSH, which is believed to be important for maintaining healthy receptor sensitivity throughout the body. More advanced TRH analogs, such as Taltirelin, have been developed with modifications to their peptide structure. These changes are designed to make them more resistant to degradation by serum enzymes and to have a higher affinity for TRH receptors in the central nervous system, potentially offering more targeted effects with a longer duration of action.

The body’s response to stress is not isolated; high levels of cortisol can suppress the conversion of T4 to active T3, creating a functional thyroid slowdown.

Why Does Systemic Health Matter?

No hormonal axis operates in a vacuum. The HPT axis is in constant communication with other systems, most notably the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, which governs the body’s stress response. Chronic physiological or psychological stress leads to sustained elevation of the hormone cortisol. Elevated cortisol has a direct inhibitory effect on the thyroid system in two ways:

- Suppression of TSH ∞ High cortisol levels can blunt the pituitary’s release of TSH, reducing the primary signal to the thyroid gland.

- Inhibition of T4-to-T3 Conversion ∞ Cortisol directly impairs the function of the deiodinase enzymes that convert inactive T4 into active T3.

This creates a scenario where an individual under chronic stress may have adequate T4 levels from medication, but their body is unable to convert it to the active form needed by the cells. This is a prime example of where a simple replacement model may fall short, as it does not address the underlying systemic imbalance that is hindering hormone function. A therapeutic approach that considers these interconnections is essential for comprehensive wellness.

Academic

A sophisticated understanding of thyroid physiology requires moving beyond the measurement of hormones circulating in the bloodstream and considering the final, critical step in their journey ∞ entry into the target cell and interaction with its nucleus.

This is the arena of cellular transport and hormone resistance, a field that reveals the profound limitations of relying solely on serum lab values to assess a patient’s true metabolic state. The ultimate efficacy of any thyroid therapy, whether conventional or peptide-based, depends on the successful completion of this microscopic voyage.

The Cellular Gateway Thyroid Hormone Transporters

For many years, it was assumed that lipophilic molecules like thyroid hormones could diffuse passively across the cell membrane. It is now definitively established that their entry into cells is a highly regulated, energy-dependent process facilitated by specific transmembrane proteins.

Several families of transporters are involved, but one has been identified as uniquely specific and critical for thyroid hormone transport ∞ Monocarboxylate Transporter 8, or MCT8. The gene encoding MCT8, SLC16A2, is located on the X chromosome. MCT8 is responsible for transporting thyroid hormones, particularly the active T3 hormone, across the cell membrane in numerous tissues, with its function being especially vital in the brain.

What Is the Clinical Significance of Cellular Transport?

The clinical relevance of MCT8 is dramatically illustrated by a rare genetic condition known as Allan-Herndon-Dudley Syndrome (AHDS). Males with a mutation in the SLC16A2 gene have a non-functional MCT8 transporter. The consequences are devastating, leading to severe psychomotor retardation and neuromuscular impairment.

The biochemical profile of these patients is extraordinarily revealing ∞ they exhibit very high levels of circulating T3, low-to-normal T4, and non-suppressed TSH. This creates a paradoxical state. From the perspective of the bloodwork, the body appears to be in a state of hyperthyroidism due to the excess T3.

However, because this T3 cannot effectively enter crucial cells like neurons, the brain exists in a state of profound hypothyroidism. The high peripheral T3 levels are a result of the hormone being unable to enter cells, causing it to accumulate in the bloodstream, while also leading to thyrotoxic effects in tissues where transport is less MCT8-dependent, such as the liver and muscles.

The diagnosis of Allan-Herndon-Dudley Syndrome provides definitive proof that normal or even high serum thyroid hormone levels can coexist with severe tissue-specific hypothyroidism.

This syndrome serves as a powerful lesson in endocrine physiology. It demonstrates that the concentration of a hormone in the blood is merely a measure of its availability. Its biological effect is entirely contingent on its ability to reach its intracellular destination. While AHDS is a rare genetic disorder, it highlights a physiological principle with broader implications.

Subtler inefficiencies or polymorphisms in transporter genes like MCT8 could potentially contribute to the variable responses seen in patients treated for hypothyroidism, where some individuals continue to report symptoms of cognitive fog or low energy despite normalized serum TSH.

| Tissue/Compartment | Serum (Bloodstream) | Central Nervous System (Brain) | Peripheral Tissues (e.g. Liver) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T4 Level | Low to Normal | Very Low | Normal |

| T3 Level | High | Very Low (Hypothyroid State) | High (Thyrotoxic State) |

| Physiological State | Biochemically Hyperthyroid | Functionally Hypothyroid | Functionally Hyperthyroid |

How Does This Relate to Therapeutic Choices?

This deep dive into cellular transport provides a new lens through which to compare conventional and peptide-based therapies. Neither approach can correct a fundamental genetic defect in a transporter like MCT8. However, acknowledging this layer of complexity challenges the sufficiency of a therapeutic model that defines success solely by the normalization of serum TSH.

A systems-biology perspective, which is more aligned with the philosophy of peptide therapy, inherently appreciates that multiple points of potential failure exist within a biological pathway.

- A Replacement Model’s Blind Spot ∞ A conventional approach that successfully normalizes TSH with levothyroxine may resolve the issue of hormone production but remains blind to potential issues in transport or cellular utilization. The therapeutic endpoint is met in the blood, but not necessarily in the cell.

- A Systems-Regulation Perspective ∞ While peptide therapies like TRH analogs also primarily influence upstream production, their foundational principle is the restoration of a physiological communication cascade. This philosophy is more amenable to a future of medicine that seeks to understand and influence the entire pathway, from hypothalamic signal to nuclear receptor binding. The research into peptide-based agents is part of a broader movement to find molecules that can modulate specific biological processes with high precision, which may one day include influencing cellular transport mechanisms.

The future of endocrinology lies in developing a more granular understanding of these processes. The journey of a hormone is not complete until its message is delivered and received. This requires looking past the messengers in the bloodstream and focusing on the handshake at the cellular door.

References

- Visser, T. J. “Thyroid hormone transporters and resistance.” Endocrine, 2013.

- Bernal, J. et al. “Thyroid hormone transporters ∞ functions and clinical implications.” Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 2015.

- Helmreich, D. L. et al. “Relation between the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis during repeated stress.” Neuroendocrinology, 2005.

- Wiersinga, W. M. et al. “Evidence-based use of levothyroxine/liothyronine combinations in treating hypothyroidism ∞ a consensus document.” Thyroid, 2021.

- Nillni, E. A. “Biology of pro-Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone-Derived Peptides.” Endocrine Reviews, 1999.

- Gelato, M. C. et al. “Tesamorelin, a GHRH analog, in HIV-infected patients with abdominal fat accumulation.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2004.

- Schwartz, M. W. et al. “The hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis and the regulation of body weight.” The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 1999.

- Mullur, R. et al. “Thyroid hormone action.” Physiological Reviews, 2014.

- “Levothyroxine ∞ Uses, Interactions, Mechanism of Action.” DrugBank Online, Accessed July 2024.

- “Liothyronine ∞ Uses, Interactions, Mechanism of Action.” DrugBank Online, Accessed July 2024.

Reflection

Viewing Your Biology as a System

The information presented here offers a framework for understanding the body not as a collection of independent parts, but as a deeply interconnected system. The language of symptoms ∞ the fatigue, the cold, the mental slowness ∞ is a form of communication. It is the system reporting on its operational status. The journey toward wellness begins with learning to interpret this language, using clinical data not as a final judgment, but as one of several dialects in a complex conversation.

Your personal health narrative is unique. The interplay between your genetics, your environment, your stress levels, and your cellular machinery creates a biological signature that is yours alone. Understanding the principles of hormone replacement and system regulation provides you with a more sophisticated map.

It allows you to ask more precise questions and to partner with healthcare providers in a more informed way. The ultimate goal is to move from a state of passive symptom management to one of active, personalized biological calibration. What is your system communicating to you right now?