Fundamentals

The conversation around male fertility often orbits a single, powerful star testosterone. This hormonal axis is undeniably central to the entire system of male reproductive health. Yet, to focus on it exclusively is to admire the engine of a vehicle while ignoring the quality of the fuel, the integrity of the wiring, and the precision of the microscopic components that permit it to function.

Your body’s ability to construct and deploy healthy, motile, and genetically sound sperm is a process of immense biological complexity. It is a feat of cellular manufacturing that depends entirely on a consistent supply of specific, essential raw materials. These materials are the micronutrients obtained from your diet.

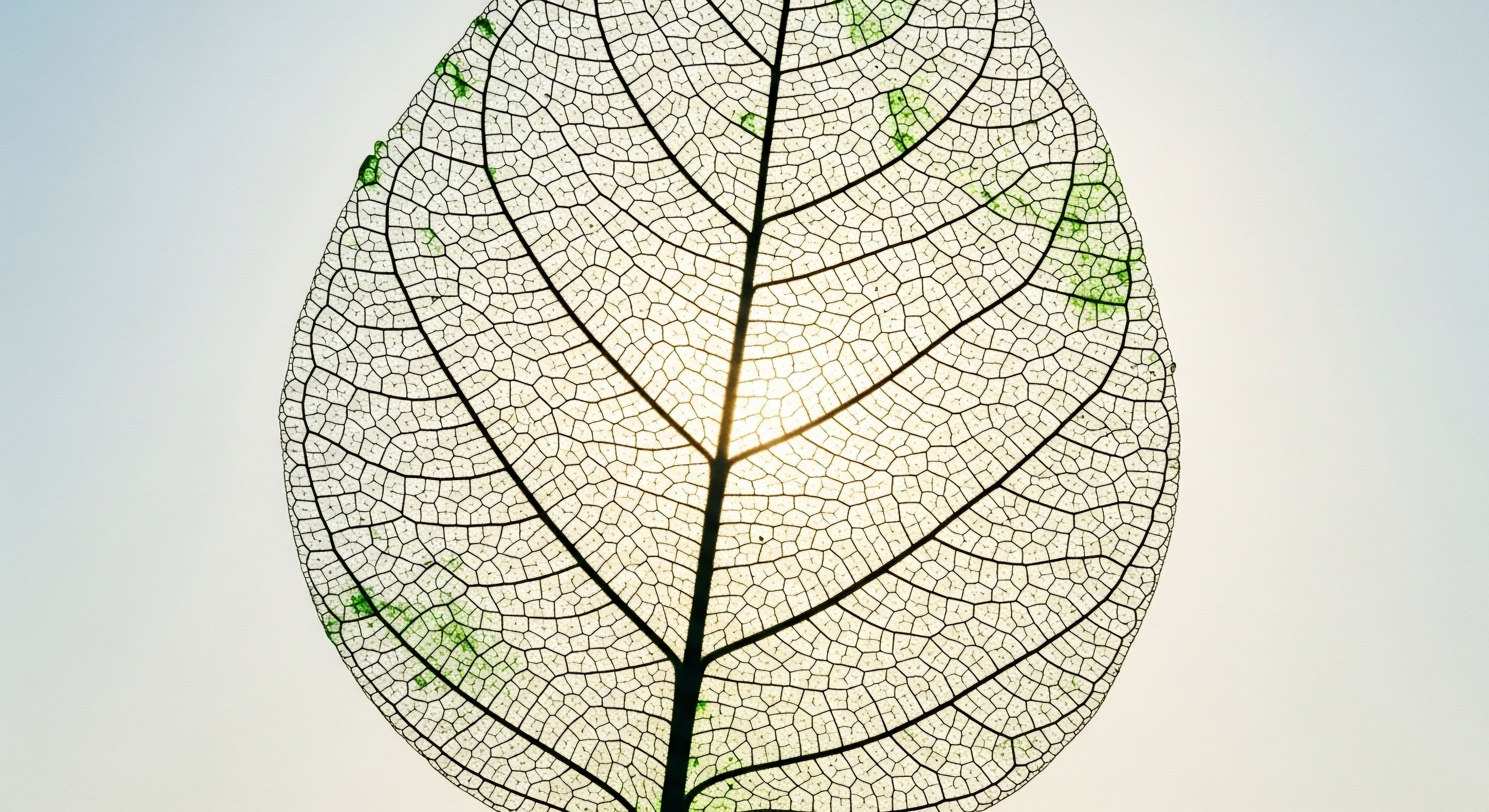

Consider the sperm cell. It is a biological marvel, tasked with a singular, critical mission. To succeed, it requires a powerful motor for propulsion, a durable yet flexible membrane to navigate complex environments, and a payload of perfectly organized genetic material. Each of these components is assembled piece by piece, molecule by molecule, in a process called spermatogenesis.

This 74-day cycle is profoundly sensitive to the biochemical environment in which it occurs. A deficiency in a key vitamin or mineral is akin to a critical parts shortage on an assembly line. The final product may look complete, but it lacks the structural integrity or functional capacity to perform its duty. This is where the lived experience of fertility challenges connects directly to the silent, cellular-level demands of the body.

The architecture of a healthy sperm cell is built from the micronutrients available in the body’s metabolic pool.

This perspective shifts the focus from a singular hormonal issue to a systemic, foundational one. It moves the locus of control, placing a significant degree of influence back into your hands through nutritional and lifestyle choices. Understanding that your daily intake of specific vitamins and minerals directly impacts the viability of your sperm provides a powerful framework for proactive health management.

The endocrine system, including testosterone production, operates within this larger systemic context. Hormones signal the start of production, but the quality of the final product is determined by the availability of these fundamental building blocks. Therefore, exploring male fertility requires us to look past the hormonal command structure and examine the logistics and supply chain that make its orders achievable.

The Cellular Assembly Line

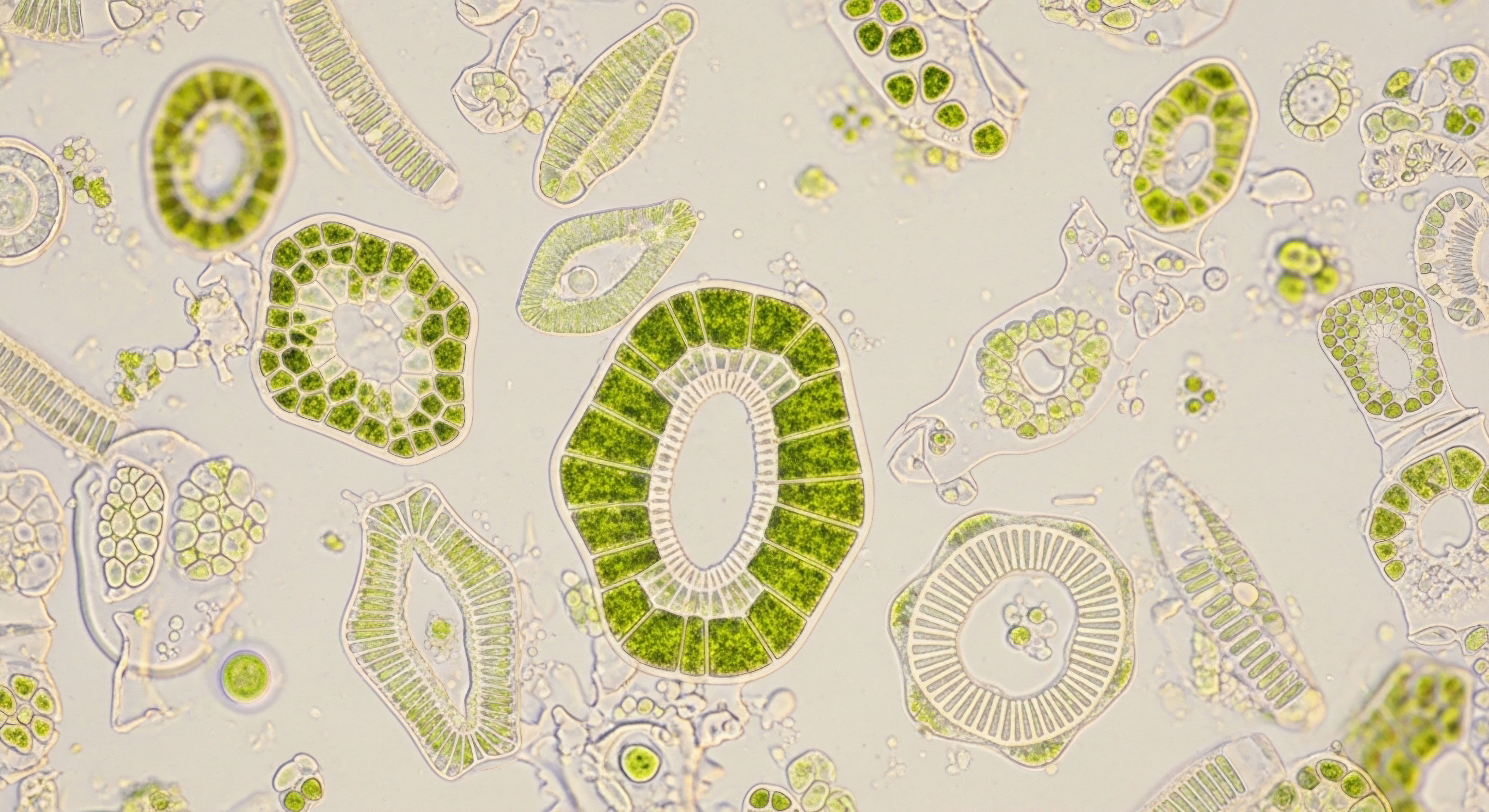

Spermatogenesis is a delicate and demanding process. Over approximately two and a half months, a single stem cell undergoes a remarkable transformation into a highly specialized, motile sperm cell. This journey involves rapid cell division, significant changes in cell shape and structure, and the precise packaging of DNA. Each stage is governed by enzymes, proteins whose function is entirely dependent on the presence of specific micronutrient cofactors.

For instance, zinc is not merely a mineral; it is a critical structural component for hundreds of enzymes. It is involved in everything from the initial cell division to the stabilization of the sperm’s tail and the proper condensation of its genetic material.

A shortage of zinc can disrupt this assembly line at multiple points, leading to a lower sperm count, poor motility, and abnormal morphology. This is a mechanical problem, a direct consequence of a missing part. Similarly, selenium is incorporated into proteins that form the structural backbone of the sperm midpiece, the cellular engine. Without adequate selenium, this engine is built improperly, compromising the sperm’s ability to generate the energy needed for its journey.

Beyond Simple Numbers

A standard semen analysis provides critical data points sperm count, motility, and morphology. These are quantitative measures. The micronutrient status of the body, however, speaks to the qualitative aspects of sperm health that are invisible to a microscope yet are determinative for successful conception.

The integrity of the DNA within the sperm head and the stability of the cell membrane are two such qualities. These are directly influenced by the balance of oxidative stress and antioxidant defenses within the reproductive tract, a balance governed by the availability of vitamins like C and E, and compounds like Coenzyme Q10.

A cell can be motile and perfectly shaped but carry damaged DNA, rendering it incapable of producing a viable embryo. This is the deeper layer of fertility, a place where nutritional science and reproductive biology converge.

Intermediate

To appreciate the direct impact of micronutrients on male fertility, we must move from the general concept of “building blocks” to the specific roles these compounds play in the intricate choreography of sperm production and function. The male reproductive system is a high-energy, metabolically active environment.

This activity, while necessary, generates byproducts, primarily reactive oxygen species (ROS). In balanced quantities, ROS are involved in normal cell signaling. In excess, they create a state of oxidative stress, which is profoundly damaging to the delicate structures of sperm. Micronutrients function as both the structural components of sperm and as the essential agents in the antioxidant defense system that protects them.

What Is the Role of Specific Micronutrients in Sperm Health?

Each micronutrient has a distinct portfolio of functions within the male reproductive system. Their actions are often synergistic, meaning their combined effect is greater than the sum of their individual parts. A deficiency in one can create a bottleneck that impairs the function of others. Understanding these specific roles allows for a more targeted and effective approach to nutritional support.

The Core Minerals Zinc and Selenium

Zinc and selenium are arguably the two most critical minerals for male fertility. Their influence extends across the entire lifecycle of a sperm cell, from initial development to final maturation and function.

- Zinc (Zn) ∞ This mineral is a master cofactor for enzymatic reactions. It is essential for the function of RNA and DNA polymerases, the enzymes that replicate and transcribe genetic material during the rapid cell division of spermatogenesis. Zinc also contributes to the structural integrity of chromatin, the complex of DNA and proteins within the sperm head. Furthermore, it plays a key role in the acrosome reaction, a critical step where the sperm releases enzymes to penetrate the egg. A deficiency can therefore lead to low sperm count, impaired DNA packaging, and a failure of fertilization.

- Selenium (Se) ∞ Selenium’s primary role is as a component of a special class of proteins known as selenoproteins. One of these, glutathione peroxidase, is a powerful antioxidant enzyme that neutralizes damaging ROS in the testes and seminal plasma. Another selenoprotein is a key structural component of the mitochondrial capsule in the sperm’s midpiece, the “engine room” that powers its motility. Selenium deficiency is directly linked to impaired motility and abnormal sperm morphology, particularly defects in the tail and midpiece.

The Antioxidant Vitamins C and E

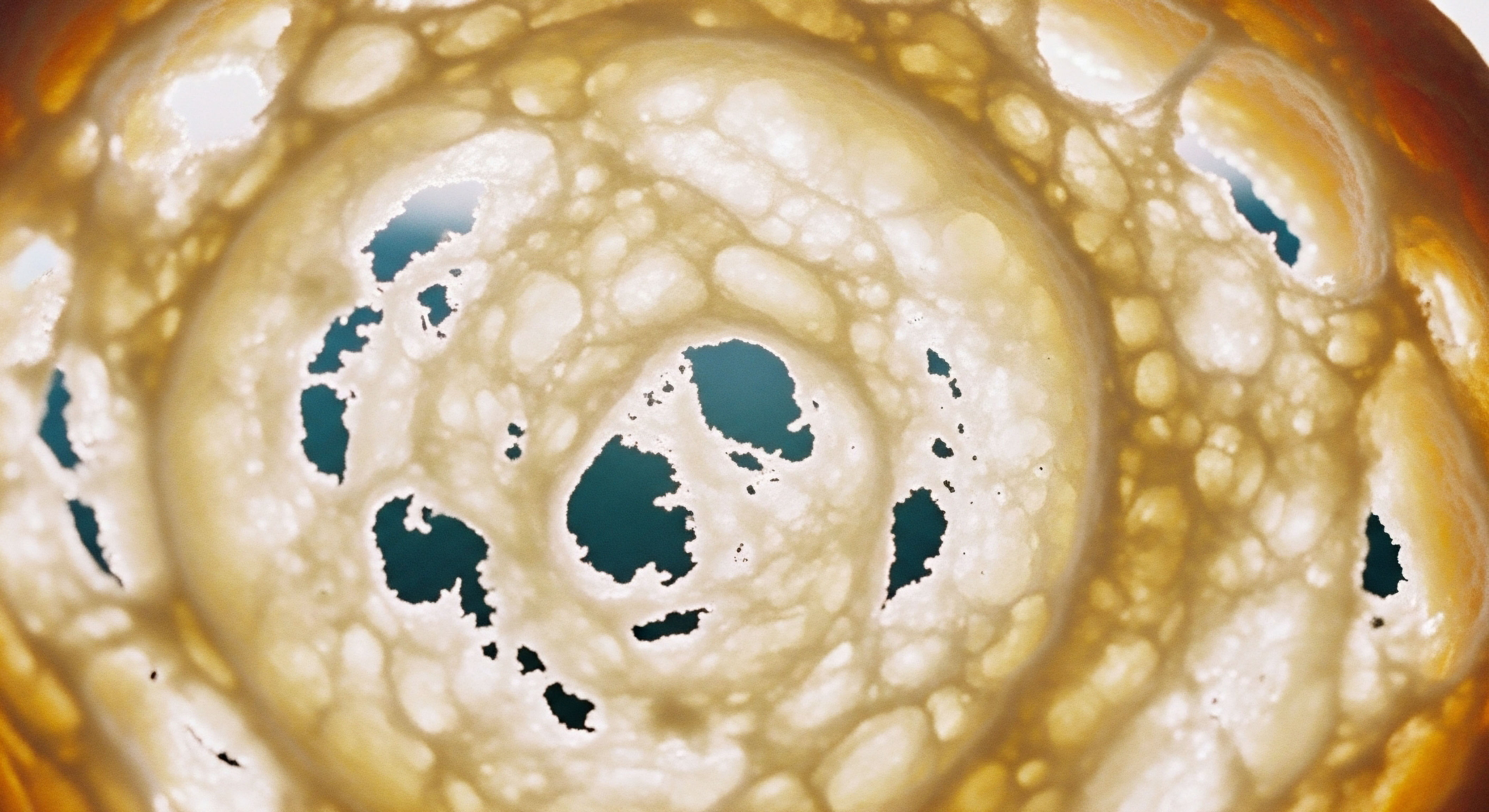

Sperm cells are uniquely vulnerable to oxidative damage. Their membranes are rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids, which are highly susceptible to lipid peroxidation by ROS, leading to stiff, non-functional membranes. Their cytoplasm is minimal, containing few of the cell’s natural antioxidant defenses. This makes them heavily reliant on the antioxidants present in the surrounding seminal fluid.

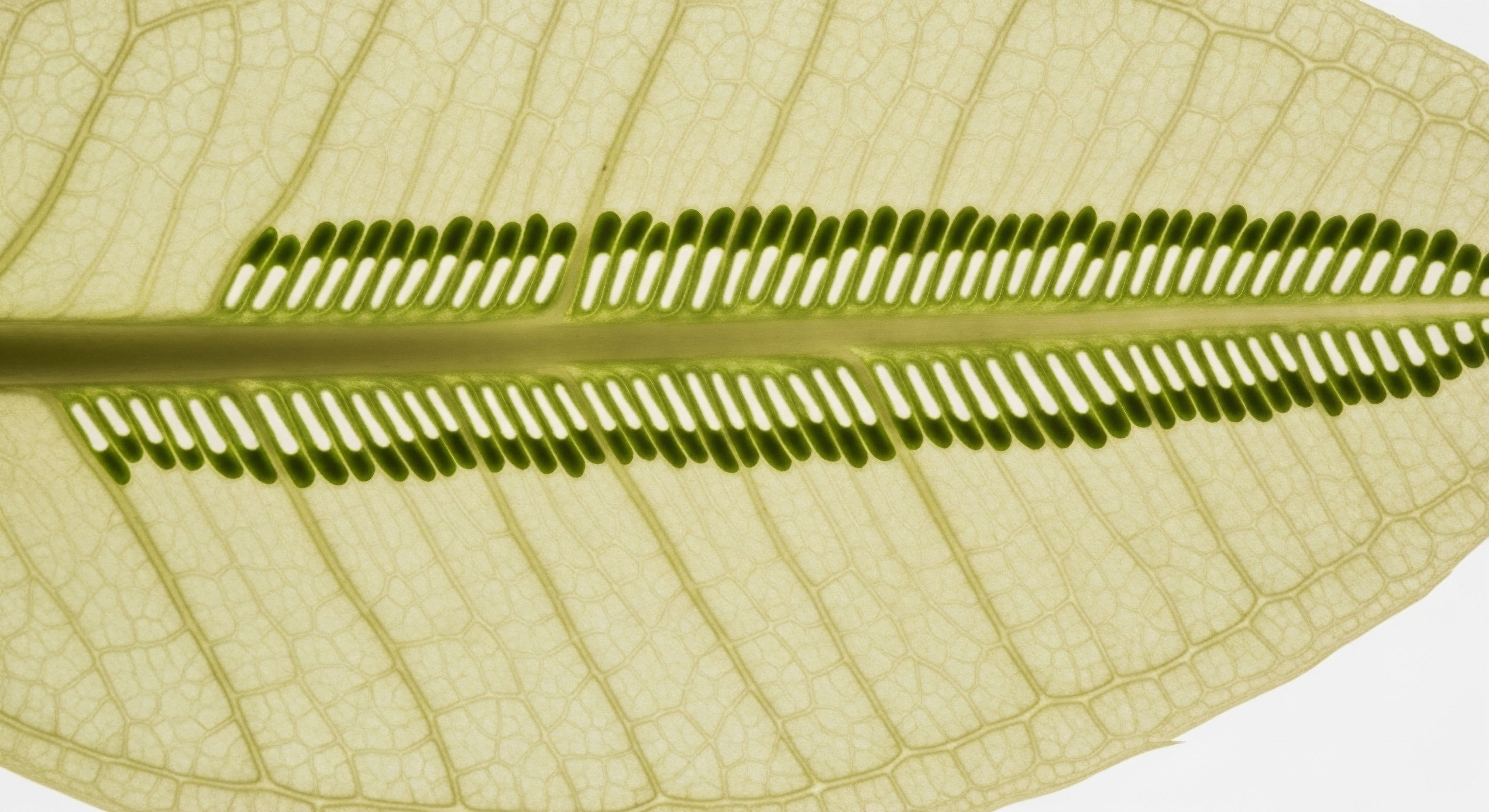

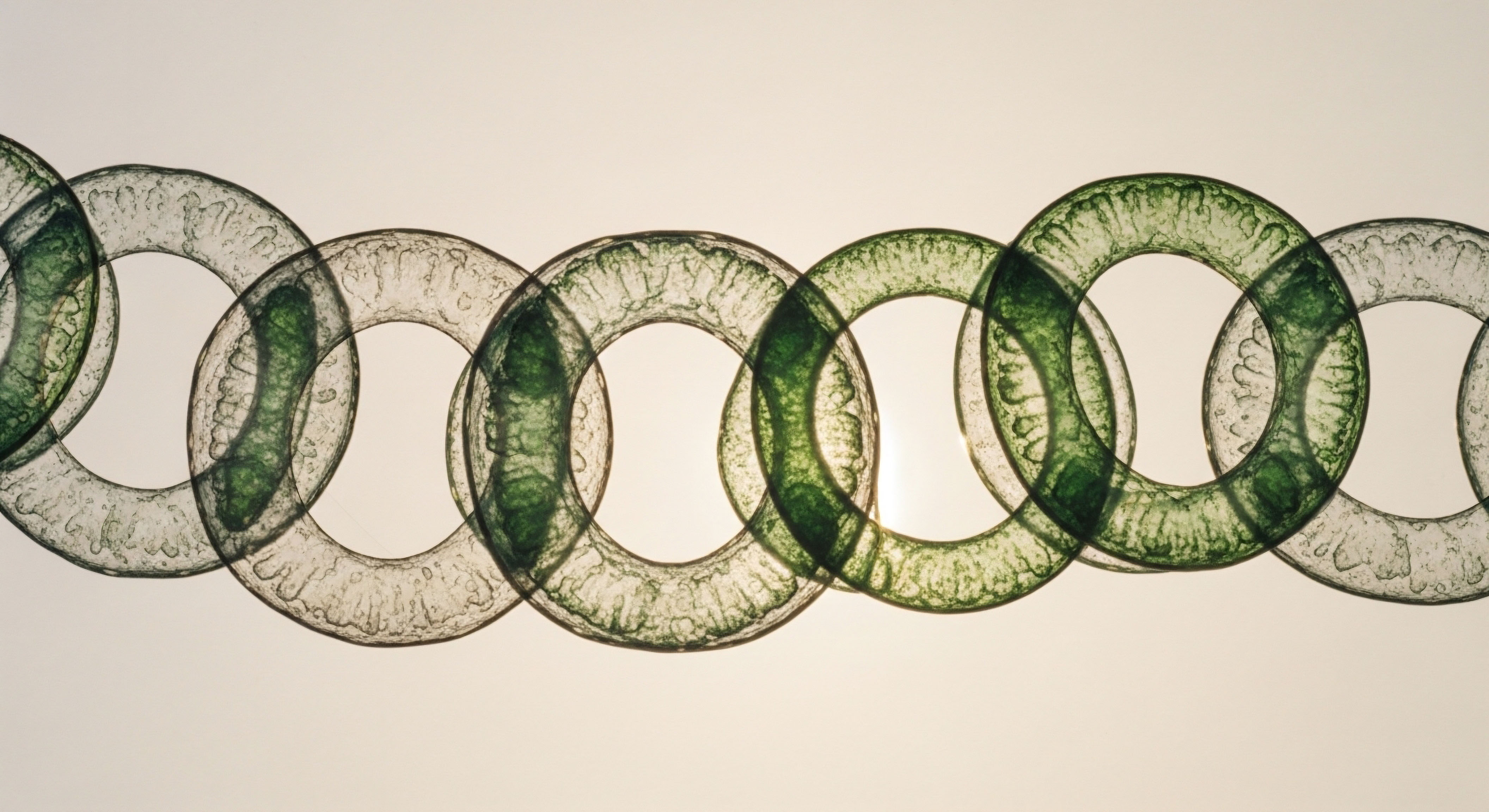

Antioxidant micronutrients form a protective shield, neutralizing the reactive molecules that threaten sperm structure and genetic integrity.

Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) is the primary water-soluble antioxidant in seminal plasma, protecting the sperm’s interior and the seminal fluid itself from ROS. Vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol) is the primary fat-soluble antioxidant, embedding itself within the sperm’s cell membrane to protect it from lipid peroxidation.

They work in concert; Vitamin E neutralizes a free radical, and Vitamin C can then regenerate the Vitamin E, allowing it to continue its protective function. This synergy is a powerful example of how multiple micronutrients create a robust defense system.

| Micronutrient | Primary Mechanism of Action | Impact of Deficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Zinc | Cofactor for DNA/RNA synthesis; chromatin stabilization; antioxidant enzyme function. | Reduced sperm count, poor morphology, impaired DNA integrity. |

| Selenium | Component of antioxidant selenoproteins (e.g. glutathione peroxidase); structural integrity of sperm midpiece. | Poor motility, tail defects, increased DNA damage. |

| Vitamin C | Water-soluble antioxidant in seminal plasma; protects sperm DNA from oxidative damage. | Increased DNA fragmentation, reduced sperm viability. |

| Vitamin E | Fat-soluble antioxidant; protects sperm cell membrane from lipid peroxidation. | Impaired motility, reduced ability to fertilize the egg. |

| Folate (Vitamin B9) | Essential for DNA synthesis and methylation; part of one-carbon metabolism. | Reduced sperm count, increased sperm aneuploidy (abnormal chromosome numbers). |

| Coenzyme Q10 | Mitochondrial energy production; potent fat-soluble antioxidant. | Reduced sperm motility and energy; increased oxidative stress. |

Folate and the Importance of Genetic Integrity

Folate, a B-vitamin, is well-known for its role in preventing neural tube defects in fetal development, but its importance begins much earlier. Folate is a critical component of the one-carbon metabolism pathway, which is responsible for two fundamental processes ∞ the synthesis of nucleotides (the building blocks of DNA) and methylation.

During the rapid cell division of spermatogenesis, an enormous amount of DNA must be synthesized accurately. Folate deficiency can lead to errors in this process, resulting in sperm with abnormal numbers of chromosomes (aneuploidy), which is a major cause of early miscarriage. The connection between folate and DNA integrity underscores how paternal nutrition is a direct factor in the health of a potential embryo.

Academic

The dialogue concerning male fertility is evolving from a quantitative assessment of semen parameters to a qualitative evaluation of the spermatozoon’s molecular and genetic payload. This advanced perspective focuses on two interconnected domains where micronutrients exert profound influence ∞ the mitigation of oxidative stress and the fidelity of epigenetic programming.

These areas move beyond the mechanics of testosterone signaling to address the very essence of what a sperm cell delivers, the integrity of its genetic blueprint and the epigenetic instructions required for successful embryonic development. A male may produce a normal quantity of motile sperm, yet these cells can be functionally compromised at a level undetectable by standard analysis.

How Does Oxidative Stress Compromise Sperm Function?

Oxidative stress represents a state of molecular imbalance where the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) overwhelms the body’s antioxidant defense capacity. Spermatozoa are exceptionally susceptible to this imbalance. Their plasma membranes possess a high concentration of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), which are primary targets for lipid peroxidation by ROS.

This process initiates a destructive chain reaction that degrades membrane fluidity, impairs the function of membrane-bound enzymes, and ultimately compromises the sperm’s motility and its ability to engage in the acrosome reaction necessary for fertilization. Concurrently, ROS can directly attack the integrity of both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA.

Mitochondrial DNA damage curtails the cell’s energy production, leading to asthenozoospermia (low motility). Nuclear DNA damage is more consequential, resulting in single- and double-strand breaks that create DNA fragmentation. While the oocyte possesses some capacity to repair this damage post-fertilization, extensive fragmentation can overwhelm this system, leading to fertilization failure, poor embryonic development, or early pregnancy loss.

The male reproductive system has an endogenous antioxidant system, including enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and glutathione peroxidase (GPx). The efficacy of this system is directly dependent on micronutrient availability. Zinc is a cofactor for SOD, and selenium is an integral component of GPx. Thus, a deficiency in these minerals directly diminishes the enzymatic shield protecting sperm from ROS.

The Epigenetic Signature of Sperm

Beyond the genetic sequence itself, sperm carries a complex layer of epigenetic information. This information, primarily in the form of DNA methylation patterns and histone modifications, does not change the DNA code but regulates gene expression in the early embryo.

These epigenetic marks are established during spermatogenesis and are critical for orchestrating the complex sequence of gene activation and silencing required for a zygote to develop properly. Paternal malnutrition is now understood to be a significant factor that can alter the sperm epigenome, with potential health consequences for the offspring.

Micronutrients and the One-Carbon Metabolism Pathway

The establishment of correct DNA methylation patterns is critically dependent on the one-carbon metabolism pathway. This metabolic cycle produces S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), the universal methyl donor for all methylation reactions in the body, including the methylation of DNA. The proper functioning of this pathway relies on several B-vitamins as essential cofactors.

- Folate (Vitamin B9) ∞ Folate is the primary carrier of one-carbon units. It receives a methyl group and transfers it into the cycle. Low folate status can directly lead to a reduced supply of methyl groups, potentially causing global hypomethylation of sperm DNA. This can result in the improper activation of genes that should be silenced, disrupting embryonic development.

- Vitamin B12 (Cobalamin) ∞ This vitamin is a required cofactor for methionine synthase, the enzyme that regenerates methionine, the precursor to SAM. A deficiency in B12 can trap folate in an unusable form and halt the entire methylation cycle, creating a functional folate deficiency even when dietary intake is adequate.

- Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine) ∞ This vitamin acts as a cofactor for enzymes in an intersecting pathway (the transsulfuration pathway) that can draw intermediates away from the methylation cycle. Its balance is important for maintaining the overall flux towards SAM production.

Disruptions in this pathway due to micronutrient deficiencies can therefore alter the epigenetic signature of sperm. Research has linked such alterations to changes in fetal development and an increased risk of metabolic diseases in the subsequent generation, a concept known as the paternal origins of health and disease.

| Parameter | Controlling Micronutrients | Consequence of Deficiency |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Fragmentation | Zinc, Selenium, Vitamin C, Vitamin E, CoQ10 | Increased single- and double-strand DNA breaks; potential for fertilization failure and miscarriage. |

| Lipid Peroxidation | Vitamin E, Vitamin C, Coenzyme Q10 | Loss of membrane fluidity, impaired motility, and compromised acrosome reaction. |

| DNA Hypomethylation | Folate, Vitamin B12, Vitamin B6, Zinc | Altered epigenetic programming, improper gene expression in the embryo, potential long-term health effects in offspring. |

| Mitochondrial Function | Coenzyme Q10, Selenium, L-Carnitine | Reduced ATP production, leading to low sperm motility (asthenozoospermia). |

Why Is This Deeper Understanding Clinically Relevant?

This molecular perspective explains why some cases of male infertility remain “unexplained” by conventional metrics. A man can present with normal sperm count and motility yet have high levels of DNA fragmentation or aberrant epigenetic patterns. These molecular defects are the downstream consequences of an suboptimal biochemical environment, often influenced by nutritional status.

Addressing micronutrient deficiencies provides a targeted therapeutic strategy to improve the fundamental quality of the sperm. It is a clinical intervention aimed at enhancing the integrity of the genetic and epigenetic information that is the father’s primary contribution to the next generation. This approach complements hormonal optimization by ensuring that the cellular machinery commanded by testosterone has all the necessary components to produce a biologically competent gamete.

References

- Salas-Huetos, Albert, et al. “The Effect of Nutrients and Dietary Supplements on Sperm Quality Parameters ∞ A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials.” Advances in Nutrition, vol. 9, no. 6, 2018, pp. 833-848.

- Fallah, A. et al. “Zinc is an Essential Element for Male Fertility ∞ A Review of Roles in Men’s Health, Germination, Sperm Quality, and Fertilization.” Journal of Reproduction & Infertility, vol. 19, no. 2, 2018, pp. 69-81.

- Smits, R. M. et al. “The impact of oxidative stress on male reproduction.” Reproduction, Fertility and Development, vol. 30, no. 8, 2018, pp. 1045-1053.

- Donkin, I. & Barres, R. “Sperm epigenetics and influence of paternal lifestyle on offspring health.” Nature Reviews Endocrinology, vol. 14, no. 12, 2018, pp. 735-748.

- Qazi, I. H. et al. “The role of selenium and selenoproteins in male reproductive function ∞ A review of the literature.” Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology, vol. 10, no. 1, 2019, p. 84.

- Gual-Frau, J. et al. “The effect of antioxidant supplementation on sperm quality, DNA fragmentation and assisted reproductive technology (ART) outcomes ∞ a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Reproductive BioMedicine Online, vol. 31, no. 5, 2015, pp. 637-646.

- Lafuente, R. et al. “Coenzyme Q10 and male infertility ∞ a meta-analysis.” Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics, vol. 30, no. 9, 2013, pp. 1147-1156.

- Lambrot, R. & Kimmins, S. “Paternal programming of health and disease ∞ the role of the sperm epigenome.” Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity, vol. 18, no. 6, 2011, pp. 385-391.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a map of the intricate biological landscape that governs male fertility. It illustrates the profound connection between the micronutrients you consume and the molecular integrity of the cells responsible for creating new life.

This knowledge serves as more than a set of clinical facts; it is a call to view your own body as a dynamic system that you can directly influence. The path to optimizing health is one of conscious participation. Consider the daily choices that build your internal biochemical environment.

What raw materials are you providing for the most critical manufacturing process your body undertakes? This journey of understanding is the first, most definitive step toward reclaiming vitality and function, not through complex intervention, but through the foundational act of nourishing the system from within.

Glossary

male fertility

micronutrients

spermatogenesis

rapid cell division

zinc

sperm count

selenium

oxidative stress

coenzyme q10

male reproductive system

reactive oxygen species

selenoproteins

lipid peroxidation

vitamin c

vitamin e

one-carbon metabolism pathway

folate

asthenozoospermia

dna fragmentation

dna methylation

one-carbon metabolism

micronutrient deficiencies