Fundamentals

You may be familiar with the profound sense of disconnection that arises when your body feels one way, yet conventional medical tests suggest everything is within a normal range. This experience of fatigue, mental fog, or emotional dysregulation, while your blood work appears unremarkable, is a valid and deeply personal challenge.

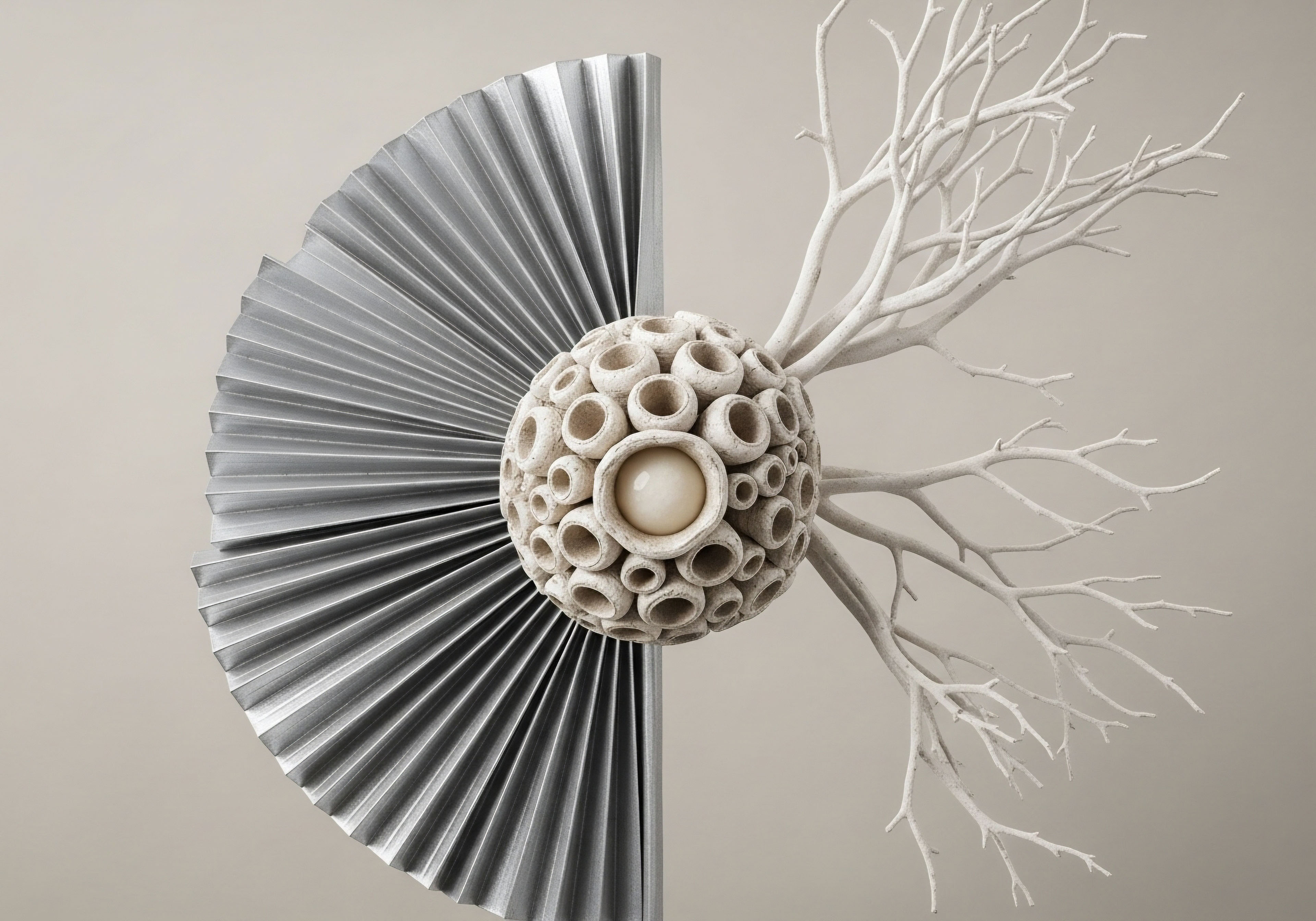

The explanation for this dissonance often resides beyond the simple measurement of hormone levels in the bloodstream. The true story unfolds at a much smaller, more intricate scale ∞ the surface of your cells, where hormonal messages are received. Your vitality is a direct reflection of your body’s ability to communicate with itself, and this cellular conversation depends entirely on the integrity of your hormone receptors.

Think of a hormone, such as testosterone or estrogen, as a precisely crafted key, carrying a vital instruction for a cell. A hormone receptor is the specific lock on the cell’s surface or within its nucleus, engineered to fit that key perfectly.

When the key enters the lock, the cell receives its instructions and carries out a specific function, such as building muscle, regulating mood, or managing metabolism. Your body produces trillions of these keys, but their effectiveness is entirely dependent on the quality and responsiveness of the locks. If the lock is rusted, misshapen, or unresponsive, the key cannot turn, and the message goes unheard. This state of reduced responsiveness is known as diminished receptor sensitivity.

The structural integrity and functional capacity of these cellular locks are maintained by a class of essential compounds your body cannot produce on its own ∞ micronutrients. These vitamins and minerals are the biological hardware, the raw materials required to build, repair, and operate your hormone receptors.

A deficiency in these foundational elements can lead to a system-wide communication breakdown, where even adequate hormone levels fail to produce their intended effects. This is the biological reality behind feeling unwell despite having “normal” labs. The messages are being sent, yet the receiving equipment is offline.

The Architects of Cellular Reception

Specific micronutrients have distinct and non-negotiable roles in the lifecycle of a hormone receptor. Understanding these roles provides a clear biochemical basis for why a nutrient-dense diet is the bedrock of endocrine health. These are not accessory molecules; they are the architectural components of your internal communication network.

Vitamin D the Receptor Gene Whisperer

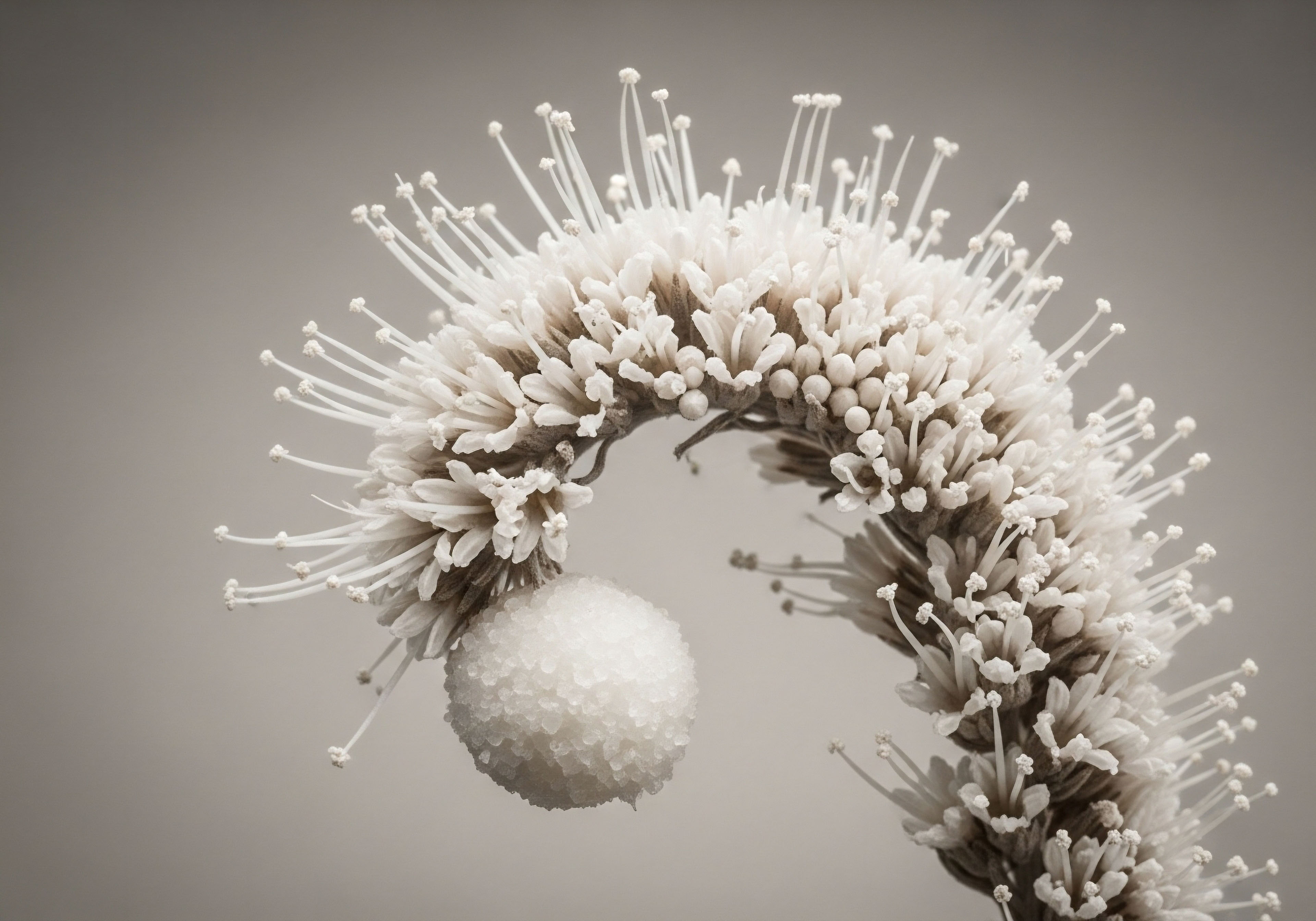

Vitamin D functions much like a hormone itself, operating as a powerful signaling molecule that directly influences the genetic blueprint for hormone receptors. It travels to the nucleus of a cell and interacts with the Vitamin D Receptor (VDR). This binding event initiates the transcription of genes that code for other hormone receptors, including those for testosterone and thyroid hormone.

An insufficiency of Vitamin D means the cellular machinery receives a weaker signal to build new, functional receptors. This results in fewer available “locks” for hormones to bind to, effectively silencing their messages before they can be delivered. Adequate Vitamin D status ensures the body is consistently manufacturing the high-quality receptors necessary for robust hormonal signaling.

Zinc the Structural Linchpin

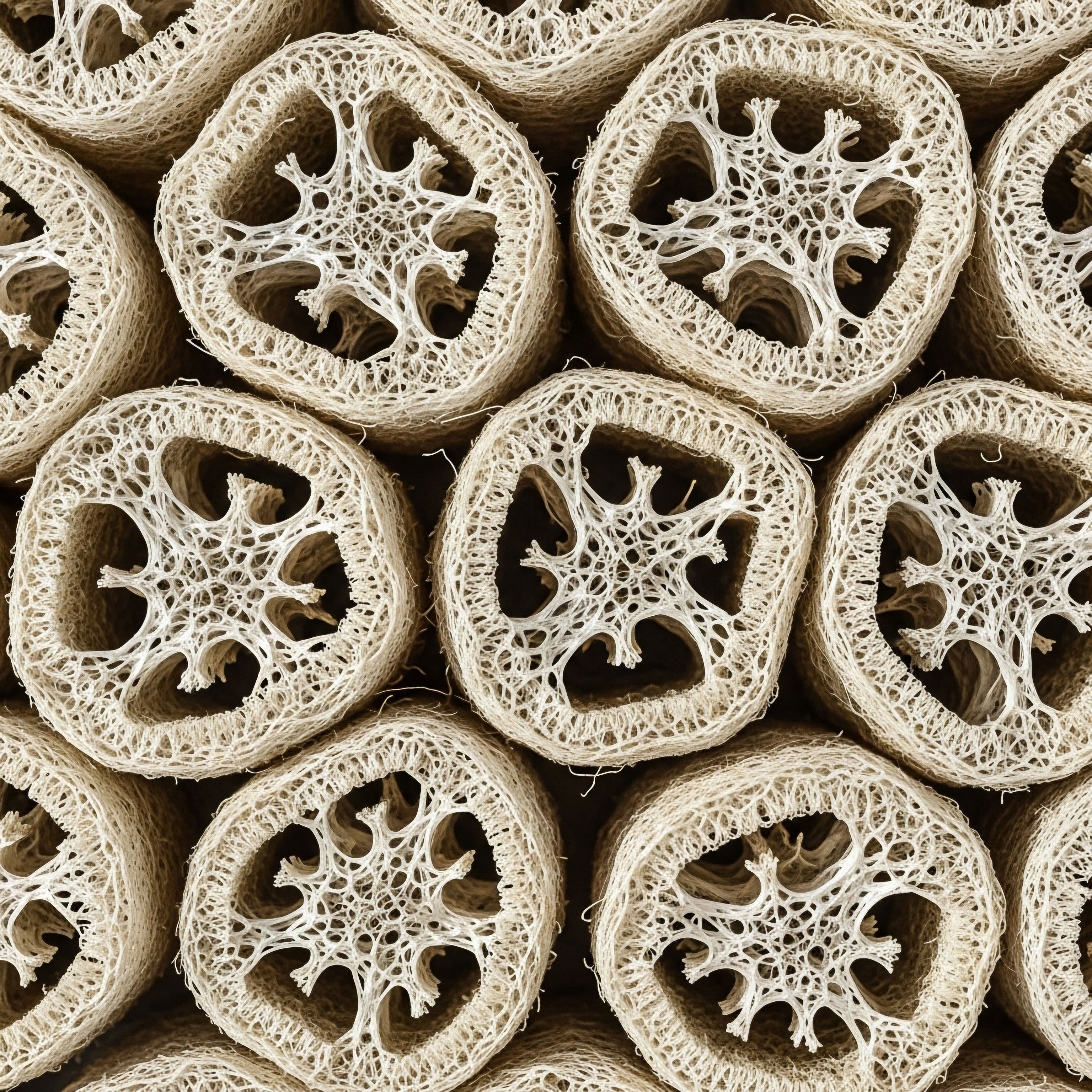

Many of the most important hormone receptors, including those for steroid hormones like testosterone, estrogen, and cortisol, as well as thyroid hormone, belong to a family of proteins that require zinc for their very structure.

These are known as “zinc-finger proteins.” The zinc atom is a central organizing element that allows the receptor protein to fold into a specific three-dimensional shape ∞ a “finger” ∞ that can physically grip onto the DNA within a cell’s nucleus.

This physical binding is the event that turns a gene “on” or “off” in response to a hormone. Without sufficient zinc, the receptor cannot form this critical finger-like structure. It becomes structurally unstable and unable to bind to DNA, rendering it completely non-functional. A zinc deficiency directly compromises the receptor’s ability to execute a hormone’s command at the genetic level.

A hormone receptor’s ability to function depends directly on the availability of specific micronutrients for its structure and activation.

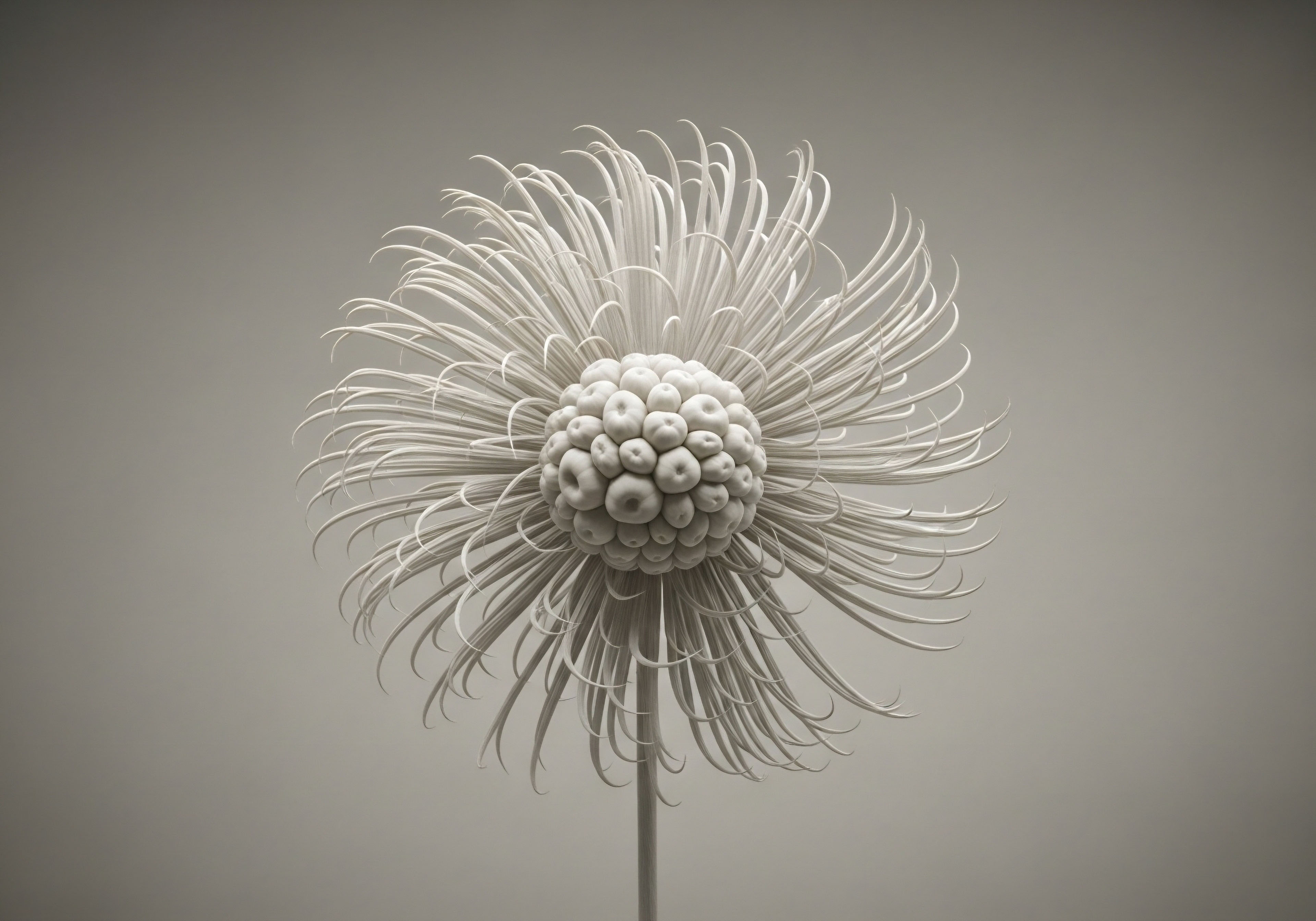

Magnesium the Energy Catalyst for Hormonal Action

Magnesium’s role is universal and indispensable, acting as a cofactor in over 300 enzymatic reactions in the body. Its connection to hormone receptor sensitivity is fundamentally tied to cellular energy. After a hormone successfully binds to its receptor, the cell must expend energy to carry out the hormone’s instructions.

This energy is supplied by a molecule called adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Every single molecule of ATP in the body must be bound to a magnesium ion to become biologically active. A deficiency in magnesium creates a cellular energy crisis. Even if a hormone binds its receptor perfectly, the cell may lack the energetic capacity to execute the resulting command.

This can manifest as fatigue, poor exercise recovery, or mood instability, symptoms often attributed to the hormonal imbalance itself, when they may stem from a downstream failure in the cell’s ability to respond.

These three micronutrients exemplify a foundational principle of endocrine health ∞ hormonal balance is a product of both hormone production and hormone reception. Addressing deficiencies in these key areas is a primary step in restoring the body’s intricate and elegant system of internal communication, ensuring that vital messages for health and vitality are both sent and received with clarity.

| Micronutrient | Primary Role in Receptor Sensitivity | Affected Hormone Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin D | Regulates the genetic expression and synthesis of new hormone receptors. | Testosterone, Thyroid, Insulin |

| Zinc | Provides essential structural integrity to nuclear receptors (zinc-finger proteins). | Testosterone, Estrogen, Cortisol, Thyroid |

| Magnesium | Enables cellular energy (ATP) production required for the cell to respond to a hormonal signal. | All systems, especially Insulin and Adrenal hormones |

Intermediate

Understanding that micronutrients are the building blocks for hormone receptors provides the foundation for a more sophisticated clinical perspective. We can now examine how specific deficiencies directly influence the efficacy of hormonal optimization protocols and create symptoms that mirror hormonal imbalances themselves.

When an individual embarks on a therapeutic regimen like Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) or thyroid support, the assumption is that the introduced hormones will find responsive and functional receptors. The presence of a micronutrient deficit can significantly undermine this process, leading to frustratingly suboptimal outcomes and a clinical picture that can be misleading.

The body does not distinguish between the source of a hormone, whether endogenous or therapeutic. Its ability to utilize that hormone remains entirely dependent on the cellular machinery of reception. Therefore, a successful clinical strategy involves preparing the cellular environment to receive these signals.

This means ensuring the body is replete with the cofactors needed for receptor synthesis, structural stability, and downstream signaling. Ignoring this aspect is akin to broadcasting a powerful radio signal to a city full of radios that are unplugged or have broken antennas. The signal is present, but the capacity for reception is impaired.

How Do Deficiencies Impact Clinical Hormone Protocols?

The interaction between micronutrients and therapeutic hormones is a critical area of consideration in personalized medicine. A patient’s nutrient status can be the determining factor between a successful therapeutic response and a muted or paradoxical one. This is particularly relevant in the context of common hormonal interventions for men and women.

The Androgen Receptor and TRT Efficacy

For a man undergoing Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT), the primary goal is to alleviate the symptoms of hypogonadism by restoring optimal testosterone levels. The clinical efficacy of this protocol, which may involve weekly injections of Testosterone Cypionate, hinges on the androgen receptor (AR). The AR is a classic zinc-finger protein.

Its ability to bind to testosterone and subsequently activate genes related to muscle mass, libido, and cognitive function is structurally dependent on zinc. A subclinical zinc deficiency can lead to a situation where, despite achieving ideal serum testosterone levels, the patient experiences only a partial resolution of symptoms.

They may notice some improvements, but the full spectrum of benefits remains elusive. This occurs because a portion of their androgen receptors are structurally compromised, unable to effectively translate the hormonal signal into a biological action. This same principle applies to protocols using Enclomiphene to stimulate endogenous production; the increased testosterone will be less effective if the receptors are not fully functional.

Thyroid Hormone Conversion and Receptor Interaction

The thyroid system offers a compelling example of a multi-stage process where micronutrients are essential. Thyroid function depends on both the production of hormones and their conversion into an active form. The thyroid gland primarily produces thyroxine (T4), which is relatively inactive.

It must be converted into triiodothyronine (T3), the active form, primarily in peripheral tissues like the liver and muscles. This conversion is catalyzed by deiodinase enzymes, which are selenium-dependent. A selenium deficiency can lead to poor T4-to-T3 conversion, resulting in symptoms of hypothyroidism even with normal TSH and T4 levels.

The story continues at the receptor level. The thyroid hormone receptor (TR) is another zinc-finger protein. Once active T3 is produced, it must bind to a functional TR to regulate metabolism.

Therefore, a concurrent deficiency in both selenium and zinc can cripple the thyroid pathway at two separate points ∞ first by impairing the production of the active hormone, and second by compromising the receptor’s ability to respond to it. A person with these deficiencies might report classic hypothyroid symptoms like fatigue, weight gain, and cold intolerance, prompting a therapeutic intervention that may be less effective than anticipated if the underlying nutrient issues are not addressed.

- Zinc Deficiency ∞ Can manifest as reduced libido, poor immune function, and slow wound healing, symptoms that directly overlap with low testosterone.

- Magnesium Deficiency ∞ Often presents as muscle cramps, poor sleep quality, anxiety, and heart palpitations, which can be confused with symptoms of perimenopause or adrenal dysregulation.

- Selenium Deficiency ∞ May lead to fatigue and hair loss, classic signs of hypothyroidism.

- Vitamin D Insufficiency ∞ Is strongly associated with mood disorders and fatigue, which are common complaints in nearly all forms of hormonal imbalance.

Metabolic Health the Insulin Receptor Connection

No discussion of hormonal health is complete without addressing insulin, the master regulator of metabolic function. The concept of insulin resistance, a state where cells become less responsive to insulin’s signal to take up glucose, is a primary example of diminished receptor sensitivity. This condition is a precursor to a host of metabolic disorders and is deeply intertwined with the function of the broader endocrine system. Several micronutrients are directly involved in maintaining the sensitivity of the insulin receptor.

Chromium, for instance, has been shown to enhance the action of insulin by improving its binding to the insulin receptor and amplifying the downstream signaling cascade. Magnesium is equally important, as it is required for the proper function of tyrosine kinase, an enzyme that is activated when insulin binds to its receptor.

A deficiency in either of these minerals can contribute to insulin resistance, forcing the pancreas to produce more insulin to achieve the same effect. This state of high insulin (hyperinsulinemia) can disrupt the balance of other hormones, including testosterone and cortisol, creating a vicious cycle of metabolic and hormonal dysregulation. Supporting insulin receptor sensitivity with targeted micronutrients is a foundational strategy for restoring systemic hormonal equilibrium.

Optimal hormonal therapy requires a cellular environment that is fully prepared to receive and act upon therapeutic signals.

By viewing hormonal health through this lens of receptor sensitivity, the clinical approach becomes more comprehensive. It shifts from a singular focus on hormone levels to a dual focus on both the signal and the receiver. This integrated perspective is essential for developing truly personalized and effective wellness protocols that address the root causes of an individual’s symptoms.

| Hormone System | Key Micronutrients | Mechanism of Impact on Receptor Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|

| Androgen System (Testosterone) | Zinc, Vitamin D | Zinc is a structural component of the androgen receptor. Vitamin D regulates androgen receptor gene expression. |

| Thyroid System (T3/T4) | Selenium, Zinc, Iron | Selenium is required for T4 to T3 conversion. Zinc is a structural component of the thyroid receptor. Iron is needed for hormone production. |

| Estrogen System | Magnesium, B Vitamins | Magnesium supports downstream signaling and energy. B vitamins are cofactors in hormone metabolism and detoxification pathways. |

| Insulin & Glucose Metabolism | Magnesium, Chromium | Magnesium is required for insulin receptor enzyme activity. Chromium enhances insulin binding and signaling. |

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of hormonal health requires a deliberate shift in perspective from systemic physiology to the precise molecular events that govern gene expression. The interface between a hormone and its target cell is a domain of intricate biochemistry, where micronutrients function as indispensable structural and catalytic components.

The concept of “receptor sensitivity” can be deconstructed into a series of discrete, quantifiable molecular processes ∞ receptor protein synthesis, conformational stability, DNA binding affinity, and post-receptor signaling cascades. A deficiency in a key micronutrient can induce a critical failure at any of these points, effectively uncoupling the endocrine signal from its intended genomic or metabolic consequence.

The most elegant and direct illustration of this principle is found within the superfamily of nuclear receptors, which includes the receptors for androgens, estrogens, progesterone, cortisol, thyroid hormone, and vitamin D. These ligand-activated transcription factors translate hormonal signals directly into changes in gene expression. Their ability to perform this function is absolutely contingent upon a specific structural motif whose integrity is maintained by a single trace mineral ∞ the zinc finger domain.

The Molecular Biology of the Zinc Finger Domain

The DNA-binding domain (DBD) of a nuclear hormone receptor is the portion of the protein that physically interacts with specific DNA sequences known as Hormone Response Elements (HREs). This interaction is the pivotal event that initiates or represses the transcription of target genes.

The DBD of these receptors is characterized by the presence of two Cys2-Cys2 zinc finger motifs. Each motif is a highly conserved protein structure wherein a single zinc ion (Zn2+) is tetrahedrally coordinated by four cysteine residues.

This coordination is not a passive association; the electrostatic interactions between the zinc ion and the sulfur atoms of the cysteine residues force the polypeptide chain into a stable, compact, finger-like fold. This specific three-dimensional conformation is a non-negotiable prerequisite for the receptor’s function.

What Is the Structural Role of the Zinc Ion?

The zinc ion acts as a structural scaffold. Without it, the protein sequence of the DBD would exist as a flexible, disordered chain, incapable of recognizing its specific HRE on the DNA molecule.

The first zinc finger contains a region, often called the P-box, which makes direct contact with the nucleotide bases in the major groove of the DNA, determining the sequence specificity of the binding. The second zinc finger contains the D-box, which is primarily involved in mediating the dimerization of the receptor on the DNA strand.

This dimerization is required for the stable binding and transcriptional activity of most nuclear receptors. A deficiency of zinc at the cellular level leads to an inability to properly form these zinc finger structures. The result is a receptor protein that, while it may be synthesized and capable of binding its hormone ligand, is conformationally inert and unable to bind to DNA. This molecular failure manifests as profound hormone resistance at the tissue level.

Experimental studies using zinc chelation have demonstrated this principle unequivocally. When zinc is removed from a purified nuclear receptor, its ability to bind to its corresponding HRE is completely abolished. This provides direct evidence that the mineral is not merely an accessory cofactor but a fundamental structural component of the receptor itself. Consequently, an individual’s zinc status is a primary determinant of the functional capacity of their entire steroid and thyroid hormone signaling apparatus.

Vitamin D Receptor as a Master Regulator of Genetic Transcription

The Vitamin D Receptor (VDR) itself is a nuclear receptor and a zinc-finger protein, but its role extends beyond mediating the effects of Vitamin D. The VDR, when activated by its ligand (calcitriol, the active form of Vitamin D), functions as a powerful transcription factor that regulates a vast network of genes, including those that code for other hormone receptors.

For example, VDR activation has been shown to upregulate the expression of the androgen receptor gene. This creates a hierarchical system of control ∞ adequate Vitamin D status is required to synthesize the very receptors that testosterone will later activate. An insufficiency of Vitamin D can therefore precipitate a state of reduced androgen sensitivity by limiting the raw number of functional receptors available in target tissues like muscle and bone.

Furthermore, magnesium is an essential cofactor for the enzymatic conversion of dietary Vitamin D into its biologically active form, calcitriol. This occurs in a two-step process in the liver and then the kidneys. Both hydroxylation steps are dependent on magnesium-requiring enzymes.

A magnesium deficiency can therefore impair the activation of Vitamin D, creating a downstream bottleneck that limits VDR activation and subsequently reduces the synthesis of other critical hormone receptors. This demonstrates the profound interconnectedness of these micronutrients, where the deficiency of one can functionally impair the entire cascade.

- Hormone Binding ∞ A steroid hormone diffuses across the cell membrane and binds to its cognate receptor in the cytoplasm or nucleus.

- Conformational Change and Dimerization ∞ Ligand binding induces a conformational change in the receptor, causing it to dimerize (pair up) with another receptor molecule.

- Nuclear Translocation ∞ The hormone-receptor complex translocates into the nucleus (if it wasn’t there already).

- DNA Binding via Zinc Fingers ∞ The zinc finger domains of the receptor’s DBD recognize and bind to the specific HRE sequence on the DNA. This step is entirely zinc-dependent.

- Recruitment of Co-activators and Gene Transcription ∞ The bound receptor complex recruits other proteins (co-activators) and the cellular transcription machinery to initiate the process of reading the gene and synthesizing messenger RNA (mRNA). This entire process is highly energy-intensive and requires a constant supply of magnesium-bound ATP.

How Does This Impact Therapeutic Interventions?

This molecular framework has direct implications for the administration of hormonal therapies like TRT or peptide-based protocols such as those using Sermorelin or CJC-1295/Ipamorelin. While peptides operate through G-protein coupled receptors on the cell surface rather than nuclear receptors, the subsequent intracellular signaling pathways that lead to the synthesis and release of growth hormone are profoundly energy-dependent, requiring magnesium.

For nuclear-acting hormones like testosterone, the clinical implication is even more direct. Administering exogenous testosterone into a zinc-deficient system is a strategy of limited efficacy. The therapeutic signal is being provided, but the molecular apparatus required to transduce that signal into a genomic action is compromised.

A truly academic and clinically effective approach must therefore involve a biochemical recalibration of the patient’s micronutrient status to ensure the entire signaling pathway, from receptor structure to final gene transcription, is fully operational.

References

- Pizzorno, Joseph E. “Mitochondria Are the Central Target of Organ-Specific Autoimmunity.” Integrative Medicine (Encinitas, Calif.), vol. 19, no. S1, 2020, pp. 8 ∞ 14.

- Razavi, M. et al. “Magnesium-Zinc-Calcium-Vitamin D Co-supplementation Improves Hormonal Profiles, Biomarkers of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome ∞ a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial.” Biological Trace Element Research, vol. 177, no. 2, 2017, pp. 21-28.

- Smail, M. A. et al. “Zinc’s Influence on Hormonal Health ∞ An Essential Mineral in Endocrine Disorders.” Rupa Health, 12 Jan. 2024.

- Lopresti, Adrian L. “The Effects of Psychological and Environmental Stress on Micronutrient Concentrations in the Body ∞ A Review of the Evidence.” Advances in Nutrition, vol. 11, no. 1, 2020, pp. 103-112.

- Wegmüller, R. et al. “Zinc absorption by young adults from supplemental zinc citrate is comparable with that from zinc gluconate and higher than from zinc oxide.” The Journal of nutrition, vol. 144, no. 2, 2014, pp. 132-136.

- Ghavami, A. et al. “The effect of vitamin D supplementation on hormonal and metabolic parameters in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome ∞ A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Journal of Ovarian Research, vol. 14, no. 1, 2021, p. 147.

- Forman, J. P. et al. “Effect of vitamin D supplementation on blood pressure in blacks.” Hypertension, vol. 61, no. 4, 2013, pp. 779-785.

- Schwalfenberg, Gerry K. and Stephen J. Genuis. “The Importance of Magnesium in Clinical Healthcare.” Scientifica, vol. 2017, 2017, p. 4179326.

- Laity, J. H. Lee, B. M. & Wright, P. E. “Zinc finger proteins ∞ new insights into structural and functional diversity.” Current Opinion in Structural Biology, vol. 11, no. 1, 2001, pp. 39-46.

- Fallah, A. et al. “The effects of magnesium-zinc-calcium-vitamin D co-supplementation on biomarkers of inflammation, oxidative stress and pregnancy outcomes in gestational diabetes.” BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, vol. 19, no. 1, 2019, p. 107.

Reflection

Having journeyed from the tangible experience of your symptoms to the intricate molecular ballet occurring within your cells, the connection between what you consume and how you feel becomes undeniably clear. The biological narrative is no longer one of mysterious dysfunction but of logical, addressable needs.

The human body is a system of immense precision, constantly striving for equilibrium. The knowledge that you can directly support this system at its most fundamental level ∞ by providing the specific raw materials it requires to communicate with itself ∞ is a powerful realization.

A Shift in Perspective

This understanding moves the focus from merely managing symptoms to actively cultivating a state of cellular wellness. How does this new lens change the way you view your daily choices?

When you consider that a single meal can provide the zinc required to stabilize thousands of androgen receptors or the magnesium needed to power a cell’s response to a vital signal, the act of eating transforms from a routine into a therapeutic opportunity. It reframes the health journey as a collaborative partnership with your own biology.

The information presented here is a map, detailing the mechanisms and pathways that govern your endocrine health. It illuminates the “why” behind the protocols and the “how” behind your body’s responses. The next step in this journey is deeply personal.

It involves applying this understanding to your unique context, recognizing that your body’s specific needs are written in the language of your own lived experience. The path forward is one of informed, proactive engagement with your health, built upon the foundational principle that restoring function begins with restoring communication at the cellular level.