Fundamentals

The feeling of persistent fatigue, the frustrating inability to manage your weight despite your best efforts, or the brain fog that descends at inconvenient times are all valid and real experiences. These sensations are often the body’s way of communicating a deeper imbalance within its intricate internal messaging system.

One of the most fundamental aspects of this system is the dialogue between the hormone insulin and your cells. Understanding this conversation is the first step toward reclaiming your vitality. Your body is a finely tuned biological engine, and insulin is a master key that unlocks the door for glucose, your body’s primary fuel, to enter your cells and provide energy.

When this system works efficiently, your cells are sensitive to insulin’s signal. They respond immediately, welcoming the glucose from your bloodstream and keeping your energy levels stable and your mind clear.

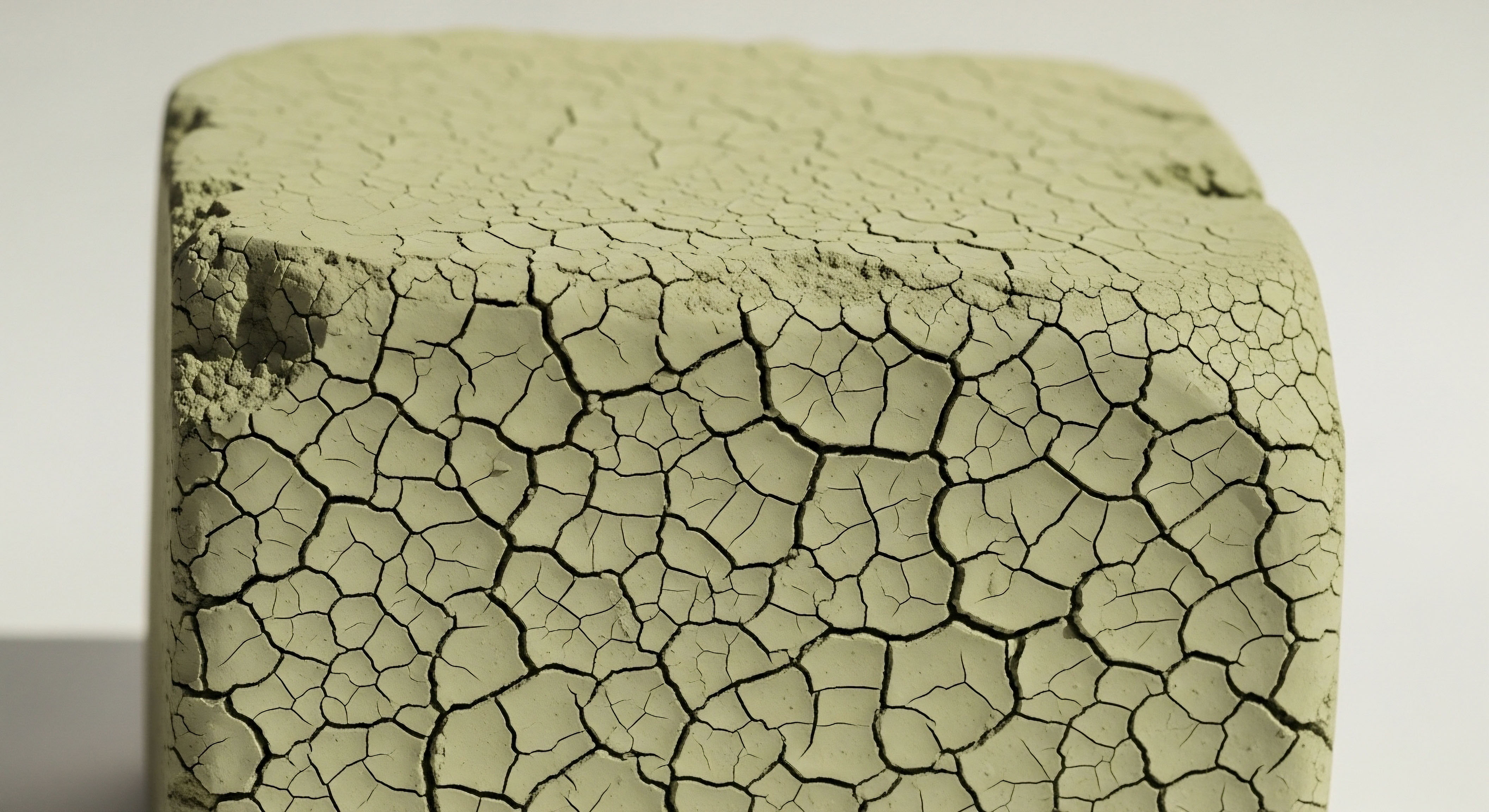

Over time, due to a combination of factors including genetics, chronic stress, and particularly our dietary patterns and activity levels, the locks on our cellular doors can become resistant to insulin’s key. The pancreas, the organ responsible for producing insulin, compensates by releasing more and more of the hormone to get the message through.

This state is known as insulin resistance. It is a condition of escalating internal noise, where the vital signal for fuel uptake is drowned out. This leads to both high levels of insulin and high levels of glucose in the bloodstream, a metabolically stressful situation that can manifest as the very symptoms you may be experiencing.

The journey to improving insulin sensitivity begins with recognizing that your lifestyle choices are the most powerful tools you have to quiet this noise and restore the clarity of this essential biological conversation.

Improving insulin sensitivity is about re-establishing a clear and efficient conversation between the hormone insulin and the body’s cells.

The Cellular Dialogue and Its Disruption

Imagine your cells as individual workshops, each requiring a steady supply of fuel to perform its specific job. Insulin, produced by the pancreas, acts as the delivery dispatcher, signaling to these workshops that a shipment of glucose has arrived in the bloodstream after a meal.

In a state of good insulin sensitivity, the workshop doors, equipped with specialized receptors, recognize insulin’s signal and open promptly, allowing glucose to enter and be used for immediate energy or stored for later. This process is seamless and efficient, maintaining a stable blood sugar level and ensuring every part of your body has the fuel it needs.

Insulin resistance disrupts this elegant system. It is akin to the locks on the workshop doors becoming rusted and difficult to turn. The insulin key still arrives, but it struggles to engage the mechanism. The pancreas, sensing that glucose is piling up in the bloodstream, works harder, sending out more and more insulin keys in an attempt to force the doors open.

This sustained overproduction of insulin, a condition called hyperinsulinemia, is a key feature of insulin resistance. While it might work as a temporary solution, it creates a cascade of downstream problems. The cells become even less responsive to the constant barrage of insulin signals, and the persistently high levels of glucose in the blood can be damaging to blood vessels and organs over time.

This is the biological reality behind the feelings of energy crashes, cravings for sugar, and the accumulation of visceral fat, particularly around the abdomen.

Lifestyle as the Primary Intervention

The most empowering aspect of understanding insulin resistance is the knowledge that it is profoundly influenced by daily habits. Lifestyle interventions are the cornerstone of restoring insulin sensitivity because they directly address the root causes of the cellular miscommunication. These interventions can be categorized into three main areas of influence:

- Dietary Modifications ∞ The food you consume has the most direct impact on your blood sugar and insulin levels. A diet high in refined carbohydrates and sugars causes rapid and large spikes in blood glucose, forcing the pancreas into overdrive. Conversely, a diet rich in whole foods, fiber, healthy fats, and adequate protein helps to moderate this response. Fiber, in particular, slows down the absorption of sugar, leading to a more gradual rise in blood glucose and a less demanding insulin signal.

- Physical Activity ∞ Exercise acts on insulin sensitivity through multiple powerful mechanisms. During physical activity, your muscles can take up glucose from the bloodstream without needing much, if any, insulin. This provides an alternative pathway for glucose utilization, immediately lowering blood sugar levels. Regular exercise also improves the efficiency of the insulin receptors on your muscle cells, effectively “oiling the locks” so they respond better to insulin’s signal in the long term. Both aerobic and resistance training have been shown to have beneficial effects.

- Stress Management and Sleep ∞ Chronic stress and inadequate sleep contribute to hormonal imbalances that can worsen insulin resistance. The stress hormone cortisol, for instance, can raise blood sugar levels to prepare the body for a “fight or flight” response. When stress is chronic, cortisol levels remain elevated, contributing to persistently high blood glucose and insulin resistance. Prioritizing sleep and incorporating stress-reduction techniques are thus essential components of a holistic approach to improving metabolic health.

By making conscious choices in these areas, you are not merely treating symptoms; you are fundamentally recalibrating your body’s metabolic machinery. You are providing the right conditions for your cells to once again become exquisitely responsive to insulin, paving the way for sustained energy, mental clarity, and long-term well-being.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational understanding of insulin resistance, we can examine the specific biochemical and physiological mechanisms through which lifestyle interventions exert their beneficial effects. These interventions are powerful because they target the very pathways that have become dysfunctional.

Improving insulin sensitivity is a process of systemic recalibration, influencing how different tissues ∞ primarily skeletal muscle, the liver, and adipose tissue ∞ communicate and function. The effectiveness of lifestyle changes lies in their ability to induce specific molecular adaptations within these tissues, leading to a more efficient and harmonious metabolic environment.

The distinction between peripheral and hepatic insulin sensitivity is a key concept at this level of understanding. Peripheral insulin sensitivity largely refers to the ability of skeletal muscle and adipose tissue to take up glucose from the blood in response to insulin.

Hepatic insulin sensitivity, on the other hand, relates to the liver’s ability to suppress its own production of glucose when insulin is present. In a state of insulin resistance, both of these processes are impaired. Lifestyle interventions work by addressing both of these facets, often through distinct yet complementary mechanisms.

For instance, a dietary change might primarily impact hepatic insulin sensitivity by reducing liver fat, while exercise might have a more pronounced effect on peripheral insulin sensitivity by enhancing glucose uptake in the muscles.

The Role of Diet in Modulating Insulin Signaling

Dietary interventions influence insulin sensitivity through several interconnected pathways, extending beyond simple calorie control. The composition of the diet, particularly the type and amount of carbohydrates and fats, plays a significant role in modulating the insulin signaling cascade.

A key mechanism involves the reduction of lipotoxicity, a state where the accumulation of certain fat metabolites in non-adipose tissues like the liver and muscle interferes with insulin signaling. A diet lower in refined carbohydrates and unhealthy fats can decrease the burden on the liver, reducing the accumulation of ectopic fat and thereby improving hepatic insulin sensitivity. This allows the liver to become more responsive to insulin’s signal to shut down glucose production.

Furthermore, the types of amino acids consumed can also have an impact. Research has shown that interventions improving both peripheral and hepatic insulin sensitivity are associated with decreases in circulating branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), particularly valine. This suggests that dietary patterns that do not overload the body with these specific amino acids may be beneficial.

The inclusion of high-fiber foods also plays a crucial role by modulating the gut microbiota. A healthy gut microbiome can produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, which have been shown to improve insulin sensitivity and reduce inflammation.

Strategic dietary changes can improve insulin sensitivity by reducing ectopic fat accumulation in the liver and muscle and by favorably altering the profile of circulating metabolites.

Comparing Dietary Approaches

While many dietary patterns can improve insulin sensitivity, they often work through slightly different mechanisms. The table below outlines some common approaches and their primary modes of action.

| Dietary Approach | Primary Mechanism of Action | Key Food Components |

|---|---|---|

| Low-Glycemic Diet | Reduces the magnitude of post-meal blood glucose spikes, lessening the demand on the pancreas for insulin production. | Complex carbohydrates, high-fiber vegetables, legumes, and lean proteins. |

| Mediterranean Diet | Combines anti-inflammatory effects from high intake of monounsaturated fats and polyphenols with the benefits of high fiber. | Olive oil, nuts, seeds, fish, whole grains, fruits, and vegetables. |

| Paleolithic-type Diet | Emphasizes whole, unprocessed foods and eliminates grains and legumes, which can lead to reductions in BCAA metabolites and ectopic fat. | Lean meats, fish, fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds. |

How Does Exercise Enhance Cellular Glucose Uptake?

Physical activity is a uniquely potent intervention for improving insulin sensitivity, particularly in skeletal muscle, which is the largest site of glucose disposal in the body. Exercise has both acute and chronic effects on glucose metabolism. The acute effect is an insulin-independent pathway of glucose uptake.

During muscle contraction, a protein called AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is activated. AMPK activation stimulates the translocation of GLUT4 glucose transporters to the cell surface, allowing glucose to enter the muscle cell without the need for insulin. This provides an immediate benefit by lowering blood glucose levels.

The chronic effects of regular exercise involve adaptations that improve the muscle’s overall insulin sensitivity. Regular training can increase the expression of GLUT4 transporters and other key proteins in the insulin signaling pathway. It also enhances mitochondrial density and function, improving the muscle’s capacity to oxidize both fat and glucose for fuel.

This increased metabolic flexibility prevents the buildup of lipid intermediates that can interfere with insulin signaling. Resistance training, in particular, increases muscle mass, which expands the body’s capacity for glucose storage and disposal. Aerobic exercise excels at improving mitochondrial function and cardiovascular health, which are also closely linked to metabolic wellness.

A study on individuals with type 2 diabetes found that a diet-only intervention improved both peripheral and hepatic insulin sensitivity, associated with a decrease in BCAA metabolites. In contrast, a combined diet and exercise intervention, while only improving peripheral insulin sensitivity, was linked to an increase in specific diacylglycerol and triacylglycerol species in the muscle and an improved rate of muscle fat oxidation.

This highlights that exercise can remodel the lipid profile within the muscle itself, making it more efficient at using fat for fuel and thereby protecting insulin signaling.

Academic

From an academic perspective, the influence of lifestyle interventions on insulin sensitivity markers is best understood as a complex interplay of systemic and tissue-specific adaptations. The molecular mechanisms are intricate, involving crosstalk between organs, modulation of inflammatory pathways, and significant shifts in the metabolic landscape.

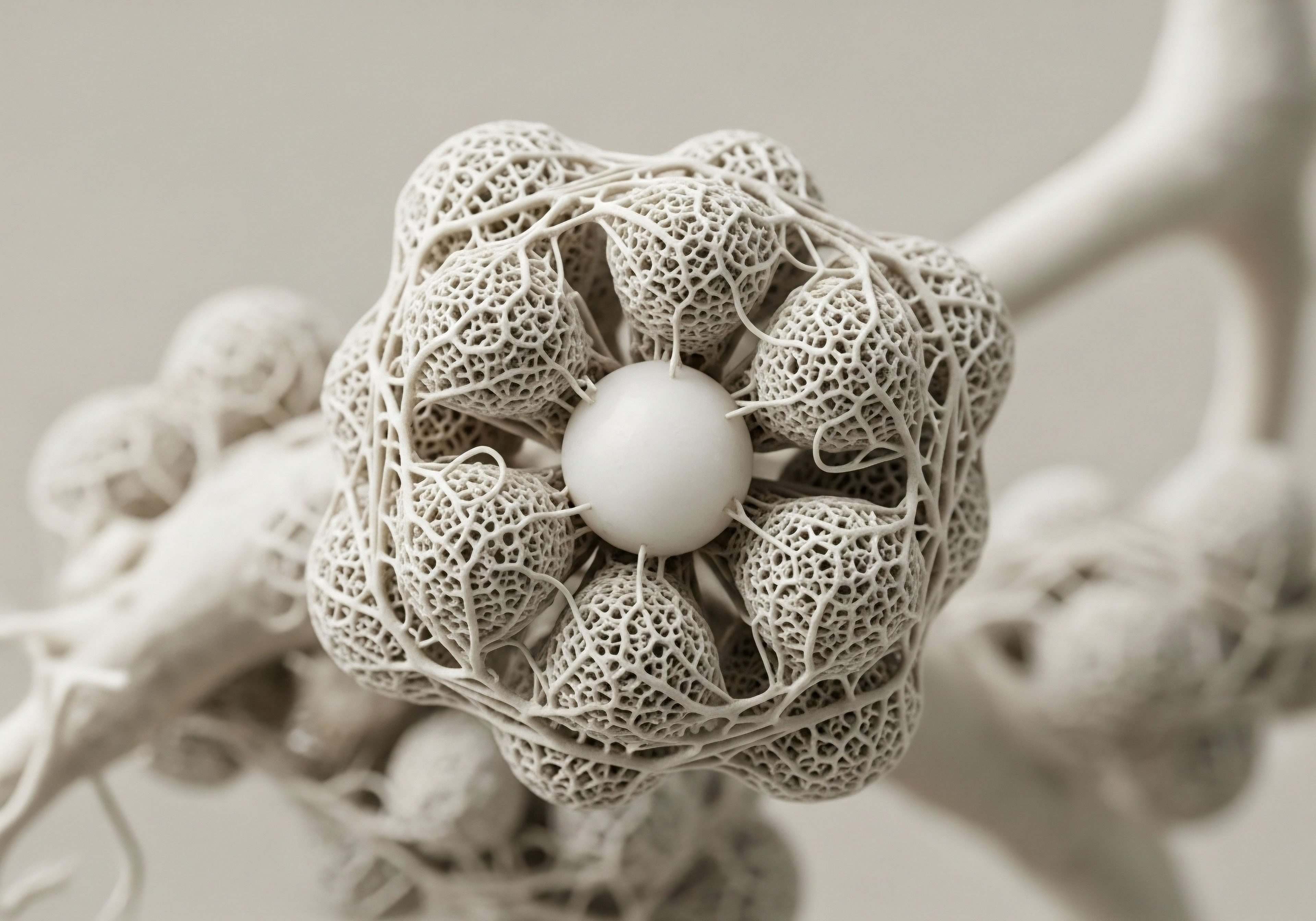

A particularly compelling area of research is the role of the gut microbiota as a central mediator in the relationship between diet and metabolic health. The gut microbiome functions as an endocrine organ, producing a vast array of metabolites that can enter systemic circulation and influence host physiology, including insulin sensitivity.

The composition of the gut microbiota is highly responsive to dietary changes, particularly the intake of different types of dietary fiber. Fermentable fibers are metabolized by gut bacteria into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as butyrate, propionate, and acetate. These SCFAs are not merely waste products; they are potent signaling molecules.

Butyrate, for example, serves as the primary energy source for colonocytes, strengthening the gut barrier. A more robust gut barrier reduces the translocation of inflammatory bacterial components like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) into the bloodstream, a phenomenon known as metabolic endotoxemia, which is a known contributor to insulin resistance.

Microbial Metabolites and Insulin Signaling

The influence of SCFAs extends beyond the gut. They can enter the portal circulation and travel to the liver, and also reach the systemic circulation, where they can directly impact insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues. SCFAs can activate G-protein coupled receptors, such as GPR41 and GPR43, on various cell types, including adipocytes and immune cells.

The activation of these receptors can modulate inflammatory responses and improve glucose homeostasis. Furthermore, SCFAs can promote the secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) from intestinal L-cells. GLP-1 is an incretin hormone that enhances glucose-stimulated insulin secretion from the pancreas, inhibits glucagon release, and slows gastric emptying, all of which contribute to better glycemic control.

Research has also begun to elucidate the role of other microbial metabolites, such as secondary bile acids and certain amino acid derivatives, in modulating metabolic health. The intricate dance between diet, the gut microbiome, and the host’s metabolic machinery underscores the importance of a systems-biology approach to understanding insulin resistance.

Lifestyle interventions, particularly those focused on a high-fiber, plant-rich diet, are effective in part because they cultivate a more favorable microbial ecosystem, leading to a metabolic milieu that promotes insulin sensitivity.

The gut microbiome acts as a critical interface between diet and host metabolism, with its metabolites playing a direct role in modulating systemic insulin sensitivity.

The Impact of Exercise on Gut Microbiota and Insulin Sensitivity

While diet is the primary driver of gut microbial composition, exercise also appears to have a modulatory effect. Physical activity can increase the diversity of the gut microbiota and enrich for beneficial species, including those that produce butyrate.

The mechanisms are still being explored but may involve alterations in gut transit time, changes in bile acid metabolism, and exercise-induced shifts in the immune system that create a more favorable environment for certain bacteria. The synergy between diet and exercise in improving insulin sensitivity may, therefore, be partly mediated by their combined positive effects on the gut microbiome.

The table below summarizes some of the key microbial-mediated mechanisms through which lifestyle interventions can influence insulin sensitivity.

| Intervention | Effect on Gut Microbiota | Key Microbial Metabolites | Downstream Effects on Insulin Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Fiber Diet | Increases diversity; enriches for fiber-fermenting species (e.g. Faecalibacterium, Roseburia). | Increased production of SCFAs (butyrate, propionate, acetate). | Enhanced GLP-1 secretion, reduced inflammation, improved gut barrier function. |

| Regular Exercise | Increases microbial diversity; may increase abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria. | Increased butyrate production. | Contributes to reduced systemic inflammation and may synergize with diet-induced changes. |

| Diet High in Polyphenols | Modulates microbial composition and function; polyphenols can act as prebiotics. | Production of various phenolic acid metabolites. | Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects that can improve insulin signaling. |

What Is the Role of Adipose Tissue Remodeling?

Beyond the gut, lifestyle interventions also induce significant remodeling of adipose tissue, which is a critical endocrine organ in its own right. In the context of obesity and insulin resistance, adipose tissue often becomes dysfunctional, characterized by chronic, low-grade inflammation. This inflamed adipose tissue releases pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6, which can directly impair insulin signaling in other tissues.

Weight loss achieved through diet and exercise helps to resolve this inflammation. It reduces the size of adipocytes, which alleviates cellular stress and hypoxia, and shifts the immune cell profile within adipose tissue from a pro-inflammatory to an anti-inflammatory state.

This “healthier” adipose tissue has an improved capacity to store lipids, preventing their spillover into other organs where they can cause lipotoxicity. Furthermore, healthy adipose tissue secretes beneficial adipokines, such as adiponectin, which has potent insulin-sensitizing effects. Therefore, the improvement in insulin sensitivity seen with lifestyle interventions is not just about losing weight; it is about restoring the metabolic and endocrine function of adipose tissue.

References

- Rojas-Gomez, L. et al. “Improved Peripheral and Hepatic Insulin Sensitivity after Lifestyle Interventions in Type 2 Diabetes Is Associated with Specific Metabolomic and Lipidomic Signatures in Skeletal Muscle and Plasma.” Metabolites, vol. 12, no. 9, 2022, p. 855.

- Asif, M. “Lifestyle Interventions to Manage Insulin Resistance.” ResearchGate, 2024.

- Yaribeygi, H. et al. “The crucial role and mechanism of insulin resistance in metabolic disease.” Journal of Translational Medicine, vol. 21, no. 1, 2023, p. 733.

- Wang, B. et al. “The role of gut microbiota in insulin resistance ∞ recent progress.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, vol. 15, 2024.

- Cleveland Clinic. “Prediabetes ∞ What Is It, Causes, Symptoms & Treatment.” Cleveland Clinic, 2023.

Reflection

You have now explored the intricate biological systems that govern your metabolic health, from the fundamental conversation between insulin and your cells to the complex ecosystem within your gut. This knowledge is a powerful starting point. It transforms abstract feelings of fatigue or frustration into an understandable physiological narrative.

Seeing your body as a responsive system, rather than a fixed state, opens up a new field of possibility. The path forward involves taking this understanding and applying it to your unique context. Your biology, your history, and your daily life are all part of the equation.

Consider where the opportunities for change lie within your own routines. The journey to reclaiming your vitality is a personal one, and it begins with the decision to engage with your own health in a more informed and proactive way.