Fundamentals

You may be reading this because you feel a persistent disconnect between how you believe you should feel and how you actually feel each day. A pervasive fatigue, a mental fog that clouds your focus, or a subtle but steady decline in your physical vitality are common experiences.

These feelings are valid data points. They are your body’s method of communicating a change in its internal environment. The journey toward reclaiming your well-being begins with understanding the language of your own biology, particularly the intricate relationship between your metabolic health and your hormonal systems.

At the center of this conversation for many men and women is testosterone. This steroid hormone is a primary regulator of muscle mass, bone density, libido, and cognitive function. When its levels decline or its action is impaired, the effects are felt system-wide.

The solution often proposed is a form of hormonal optimization, such as Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT). A compounding pharmacy is a specialized facility where pharmacists meticulously combine ingredients to create custom-dosed medications. This allows for personalized medicine that standard commercial products cannot offer. Yet, the effectiveness of any such protocol is profoundly influenced by a factor that is unique to you ∞ your individual metabolism.

Your personal metabolic signature is the soil in which hormonal therapy will either grow effectively or struggle to take root.

The Metabolic Machinery That Governs Hormones

Your metabolism is the sum of all chemical reactions that sustain life. It dictates how you extract energy from food, build and repair tissues, and regulate your internal chemistry. Two individuals can receive the exact same dose of testosterone yet experience vastly different outcomes. This variability is often rooted in their distinct metabolic profiles, which are shaped by genetics, diet, physical activity, and overall health. Several key components of your metabolic machinery directly influence how your body processes therapeutic testosterone.

Body Composition as an Endocrine Factor

The proportion of fat to muscle in your body is a critical metabolic determinant. Adipose tissue, or body fat, functions as an active endocrine organ. It produces its own hormones and enzymes that participate in a constant chemical dialogue with the rest of your body.

One of the most significant of these is the enzyme aromatase. Aromatase converts testosterone into estradiol, a form of estrogen. In individuals with a higher percentage of body fat, there is a greater abundance of aromatase. This can lead to an accelerated conversion of administered testosterone into estrogen, potentially diminishing the intended benefits of the therapy and introducing side effects associated with elevated estrogen levels.

The Role of Insulin Sensitivity

Insulin is the hormone that manages blood sugar, signaling cells to absorb glucose from the bloodstream for energy. Insulin resistance is a condition where cells become less responsive to insulin’s signal. The pancreas compensates by producing more insulin, leading to elevated levels of this hormone in the blood.

This state, a hallmark of metabolic syndrome, has a direct and powerful effect on another critical protein ∞ Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG). Insulin directly suppresses the liver’s production of SHBG. Understanding this relationship is fundamental to comprehending your hormonal health.

What Is the True Meaning of Your Lab Results?

When you review your blood work, you will see values for total testosterone and, ideally, free testosterone and SHBG. These numbers tell a story about your metabolic health.

- Total Testosterone represents all the testosterone circulating in your bloodstream. A significant portion of this is bound to proteins and is not immediately available for your cells to use.

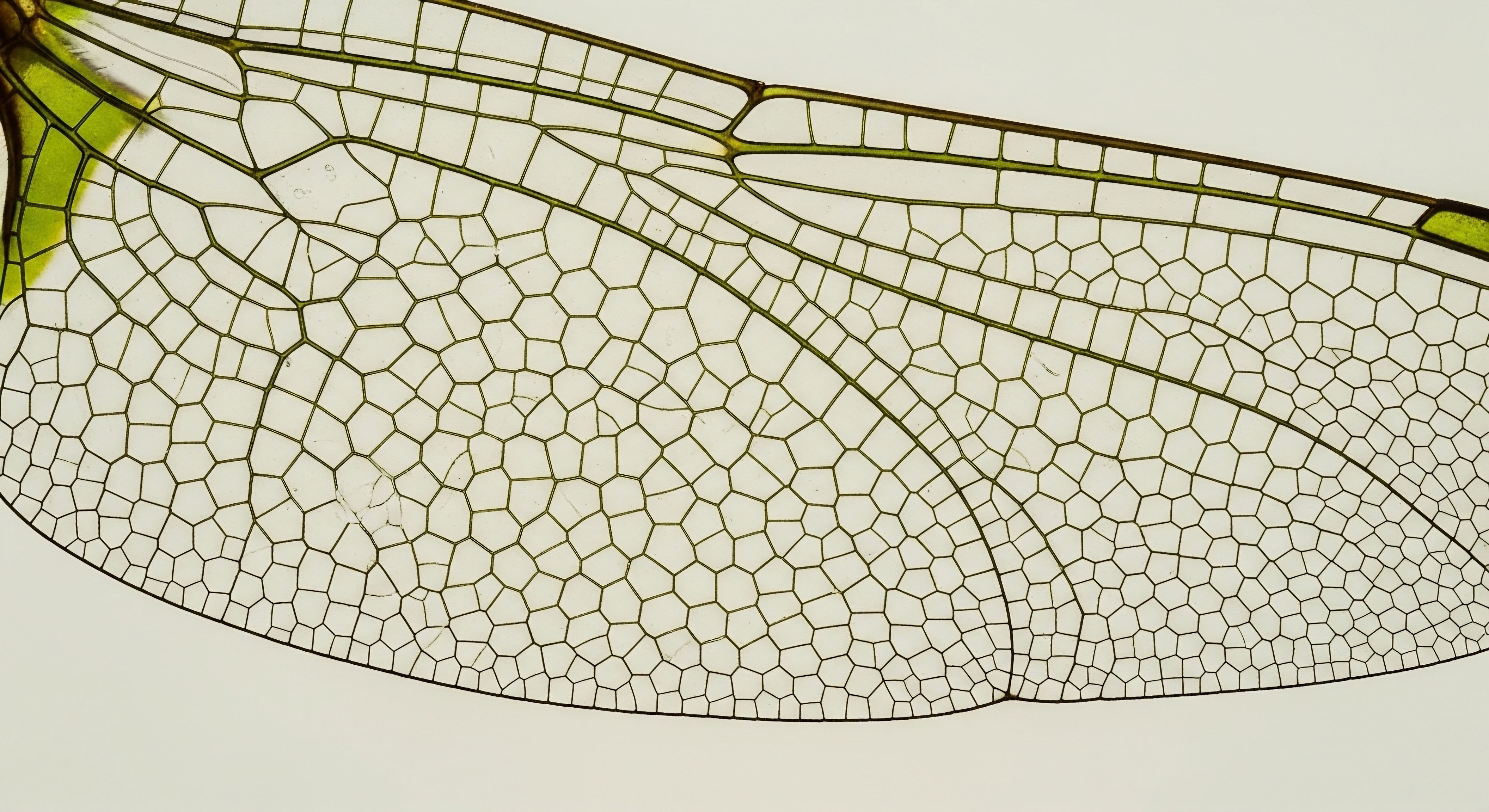

- Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) is the primary transport protein for testosterone. When testosterone is bound to SHBG, it is inactive. Think of SHBG as a carrier and a reservoir, regulating how much testosterone is available at any given moment.

- Free Testosterone is the small fraction of testosterone that is unbound and biologically active. This is the testosterone that can enter cells, bind to androgen receptors, and exert its effects on your tissues, from your brain to your muscles.

An individual with insulin resistance will often present with low SHBG levels. This metabolic state means less of their testosterone is bound up, which might initially seem beneficial. The reality is more complex. With less SHBG to act as a buffer, free testosterone may be cleared from the body more rapidly, leading to greater fluctuations and potential instability in hormone levels.

Conversely, very high SHBG can bind too much testosterone, leading to symptoms of deficiency even when total testosterone levels appear normal. Your metabolic health, specifically your degree of insulin sensitivity, directly sculpts the landscape in which your hormones operate. This biological context dictates how any therapeutic intervention will perform.

Intermediate

Understanding that your metabolic state governs hormonal efficacy is the first step. The next is to connect that knowledge to the practical realities of different testosterone delivery methods. Each protocol possesses a distinct pharmacokinetic profile, which describes how the substance is absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and eliminated by the body.

The interaction between this profile and your unique metabolic fingerprint determines the true clinical outcome. The goal of any well-designed hormonal optimization protocol is to create stable, physiological levels of the hormone, mimicking the body’s natural rhythm as closely as possible.

The delivery method is a vehicle, and its performance is entirely dependent on the terrain of your individual metabolism.

Intramuscular Injections a Weekly Bolus

Weekly intramuscular injections of Testosterone Cypionate are a common and effective protocol. This method involves administering testosterone esterified in an oil-based solution directly into a large muscle. The ester tail must be cleaved off by enzymes in your body before the testosterone becomes active, a process that creates a timed-release effect.

An injection creates a supraphysiological peak in testosterone levels within the first 24-48 hours, followed by a gradual decline over the course of the week until the next dose.

Metabolic Influence on Injection Efficacy

Your metabolic health significantly modulates this peak-and-trough cycle. An individual with a higher body mass index (BMI) and greater adipose tissue may experience a different pharmacokinetic curve. The oil-based testosterone can be sequestered in fat tissue, potentially blunting the initial peak and slightly extending the release.

The more critical metabolic factor is the increased aromatase activity in the adipose tissue. The large bolus of testosterone from an injection provides a substantial substrate for this enzyme, risking a significant conversion to estradiol. This is why an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole is often co-prescribed in TRT protocols, particularly for individuals with higher body fat.

Furthermore, the low SHBG associated with insulin resistance impacts the injection cycle. The initial surge in testosterone can lead to a higher peak of free, active hormone. This can feel potent, but it also means the hormone is available for more rapid metabolism and clearance, potentially leading to a more pronounced trough toward the end of the week, where symptoms of deficiency can reappear. For some, this cycle can create a sense of hormonal instability.

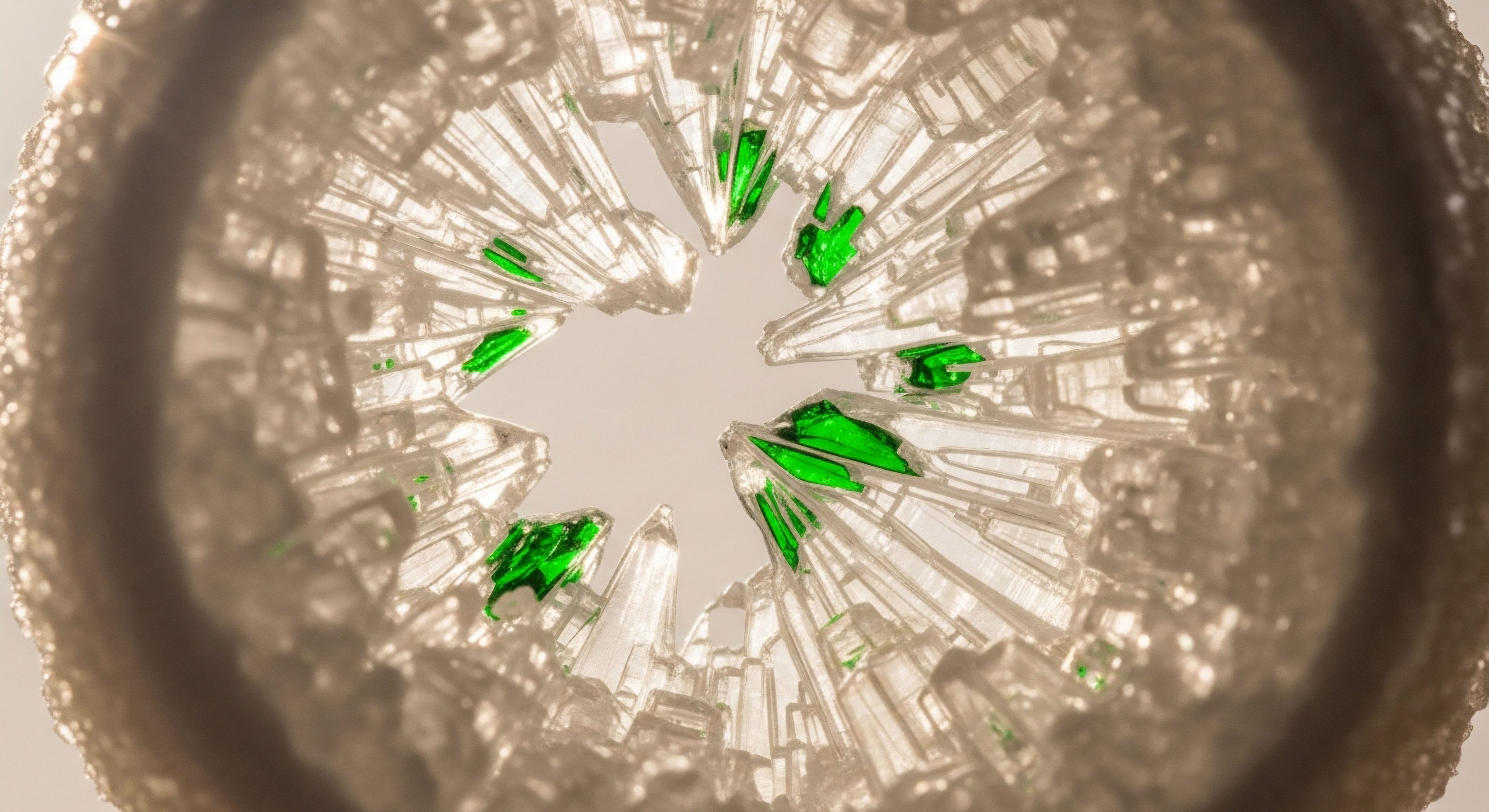

Subcutaneous Pellets a Steady State Approach

Testosterone pellets are small, crystalline implants placed under the skin during a minor in-office procedure. These pellets are designed to dissolve slowly over three to five months, releasing a consistent, low dose of testosterone directly into the bloodstream. This method is designed to avoid the peaks and troughs associated with injections, aiming for a more stable and physiological hormonal environment.

Metabolic Influence on Pellet Efficacy

The success of pellet therapy is highly dependent on the local tissue environment and vascularity. The pellets release testosterone based on cardiac output; as blood flows past them, the hormone is absorbed. Factors that affect circulation can influence their effectiveness. Chronic inflammation, a common companion to metabolic syndrome, could theoretically alter the tissue matrix surrounding the pellets and affect absorption rates.

Body composition is also a key variable. Research indicates that men with a higher BMI may have a larger volume of distribution for testosterone, which can result in lower serum testosterone levels for a given dose of pellets. This requires careful calculation by the clinician to avoid under-dosing.

Because pellets provide a steady, lower-level release, they may reduce the risk of a dramatic spike in estradiol conversion compared to injections. The stable hormone levels provided by pellets can be particularly beneficial for individuals whose SHBG levels are either very high or very low, as it avoids the wide fluctuations in free testosterone that can occur with bolus dosing.

| Delivery Method | Pharmacokinetic Profile | Interaction with High Body Fat / Insulin Resistance | Clinical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intramuscular Injections (e.g. Testosterone Cypionate) | Weekly peak-and-trough cycle. | Increased aromatization to estradiol. Faster clearance due to low SHBG. | May require an aromatase inhibitor (Anastrozole). Dosing frequency may need adjustment. |

| Subcutaneous Pellets | Steady-state release over 3-5 months. | Larger volume of distribution may require dose adjustment. Less dramatic estradiol conversion. | Provides stable hormone levels, beneficial for SHBG abnormalities. |

| Transdermal Gels/Creams | Daily application with variable absorption. | Absorption can be inefficient and inconsistent. Subcutaneous fat can affect penetration. | Requires consistent daily routine. Risk of transference to others. |

How Does Metabolic Health Affect Female Hormone Protocols?

The same principles apply to women undergoing hormonal optimization, although the dosages and goals are different. Women may be prescribed low-dose Testosterone Cypionate subcutaneously or via pellets to address symptoms like low libido, fatigue, and cognitive changes. Progesterone is also a key component, particularly for peri- and post-menopausal women.

Metabolic dysfunction in women, especially the insulin resistance seen in conditions like Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), dramatically impacts hormone balance. Low SHBG in women with PCOS can lead to higher levels of free androgens, contributing to symptoms. When prescribing testosterone, a clinician must account for this baseline metabolic state. A steady-release method like pellets might be preferable to avoid exacerbating androgenic symptoms with the peaks of an injection.

Academic

A sophisticated understanding of therapeutic endocrinology requires moving beyond simple hormone replacement and into a systems-biology perspective. The efficacy of a testosterone delivery protocol is determined by a complex interplay between the pharmacokinetics of the exogenous hormone and the host’s metabolic milieu.

The nexus of this interaction can be most clearly observed through the integrated functions of adipose tissue, the aromatase enzyme, and Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG). This triad forms a powerful regulatory axis that can either support or subvert the goals of hormonal therapy, particularly in the context of obesity and metabolic syndrome.

The Adipose-Aromatase-SHBG Axis

Adipose tissue is a highly active endocrine organ. In states of excess adiposity, it becomes a primary site for the peripheral conversion of androgens to estrogens via the aromatase enzyme. This process is not a minor metabolic footnote; it is a central driver of the hormonal dysregulation seen in obesity.

A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials has shown that while TRT can improve lean body mass, its effects on weight and metabolic markers are heavily influenced by baseline conditions and can be heterogeneous. The administration of exogenous testosterone in an individual with high adiposity provides a direct substrate for aromatization, leading to supraphysiological estradiol levels.

This iatrogenic hormonal imbalance can produce side effects such as gynecomastia, fluid retention, and mood disturbances, while simultaneously failing to resolve the primary symptoms of hypogonadism.

The Influence of Insulin on the Axis

The entire axis is further modulated by insulin. Chronic hyperinsulinemia, the hallmark of insulin resistance, exerts direct genomic effects on the liver, suppressing the transcription of the SHBG gene. This reduction in circulating SHBG has two major consequences. First, it decreases the binding capacity of the plasma, leading to a higher percentage of free testosterone and free estradiol.

Second, it accelerates the metabolic clearance rate of these hormones. An injection of testosterone enanthate or cypionate into an insulin-resistant individual results in a rapid, high-amplitude spike in free testosterone, followed by an equally rapid decline as the hormone is quickly metabolized and cleared.

This creates a state of high hormonal volatility. The elevated free testosterone is also more available for uptake into adipocytes, where it is promptly converted to estradiol by the abundant aromatase, further skewing the androgen-to-estrogen ratio.

The choice of testosterone delivery system must be considered a strategic intervention into the patient’s specific metabolic cascade.

Implications for Delivery System Selection

This systems-level view provides a clear rationale for personalizing delivery methods based on metabolic parameters. The selection process becomes a clinical decision aimed at mitigating the negative effects of the patient’s underlying metabolic dysfunction.

- Injectable Esters ∞ For an obese, insulin-resistant male, the large bolus from a weekly 200mg injection of Testosterone Cypionate can saturate the aromatase pathway, leading to a significant rise in estradiol. While co-administration of an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole is standard practice to manage this, the underlying pharmacokinetic challenge remains. The rapid clearance due to low SHBG can also lead to end-of-cycle troughs that compromise symptomatic relief.

- Subcutaneous Pellets ∞ Pellet therapy offers a potential advantage in this scenario. By releasing testosterone in a steady, zero-order fashion, it avoids the high-amplitude peaks of injections. This constant, lower-level release may be less likely to overwhelm the aromatase pathway at any single point in time, leading to more manageable estradiol levels. Furthermore, the stable serum testosterone concentration can help normalize the free hormone fraction in the presence of low SHBG, providing more consistent physiological effects and symptomatic control.

- Transdermal Systems ∞ Transdermal gels and creams present the highest degree of pharmacokinetic variability. Absorption is dependent on skin condition and can be inefficient. For an individual with obesity, the thickness of the subcutaneous fat layer can further impede consistent delivery, making it a less reliable option for achieving stable therapeutic targets.

| Metabolic Parameter | Associated Hormonal State | Predicted Response to Bolus Injection | Predicted Response to Pellet Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Adiposity (>30% Body Fat) | High aromatase activity; tendency for elevated estradiol. | Significant, rapid conversion of testosterone to estradiol, requiring management. | More gradual and manageable increase in estradiol due to steady release. |

| Insulin Resistance (Low SHBG) | Low SHBG; high free testosterone fraction; rapid hormone clearance. | High initial peak of free T, followed by a sharp trough. Hormonal volatility. | Stable serum T levels provide a more consistent free T level, mitigating volatility. |

| Lean and Insulin Sensitive (Normal SHBG) | Normal SHBG and aromatase activity. | Predictable pharmacokinetics with manageable estradiol conversion. | Provides very stable hormonal environment. Highly effective. |

Ultimately, the clinical decision-making process must integrate the patient’s metabolic phenotype into the selection of a delivery system. Laboratory data, including markers for insulin resistance (fasting insulin, HOMA-IR), inflammation (hs-CRP), and body composition, are as critical as the baseline hormone panel.

A therapeutic protocol, such as those including Gonadorelin to maintain endogenous testicular function or peptide therapies like Sermorelin to support the growth hormone axis, must be layered upon a foundational strategy that matches the testosterone delivery vehicle to the individual’s unique biological environment. This systems-based approach is the cornerstone of effective, personalized hormonal optimization.

References

- Corona, G. et al. “Testosterone replacement therapy for late-onset hypogonadism ∞ a meta-analysis and review of the literature.” Journal of sexual medicine 8.6 (2011) ∞ 1562-1576.

- Saad, F. et al. “Long-term testosterone therapy in hypogonadal men with obesity reverses the metabolic syndrome and improves glycemic control.” Obesity Facts 13.4 (2020) ∞ 384-395.

- Ding, E. L. et al. “Association of testosterone and sex hormone ∞ binding globulin with metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance in men.” Diabetes care 29.6 (2006) ∞ 1243-1248.

- Kelleher, S. et al. “Pharmacokinetic evaluation and dosing of subcutaneous testosterone pellets.” Journal of andrology 33.5 (2012) ∞ 927-937.

- Pastuszak, A. W. et al. “Comparison of the effects of testosterone gels, injections, and pellets on serum hormones, erythrocytosis, lipids, and prostate-specific antigen.” Sexual medicine 3.3 (2015) ∞ 165-173.

- Al-Qahtani, S. M. et al. “Effectiveness of testosterone replacement in men with obesity ∞ a systematic review and meta-analysis.” European Journal of Endocrinology 185.6 (2021) ∞ 799-813.

- Selvin, E. et al. “The burden of obesity and the value of weight loss.” The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 5.11 (2017) ∞ 877-885.

- Barbonetti, A. et al. “Testosterone replacement therapy.” Andrology 8.6 (2020) ∞ 1551-1566.

- Poudyal, H. et al. “SHBG and insulin resistance.” Journal of diabetes and its complications 32.1 (2018) ∞ 111-117.

- Wikipedia contributors. “Pharmacokinetics of testosterone.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 15 Jul. 2024. Web. 25 Jul. 2024.

Reflection

Charting Your Biological Path Forward

The information presented here is designed to serve as a map, translating the complex terrain of your internal chemistry into a more understandable form. You have learned that your symptoms are real data and that your unique metabolic health is the primary context for any therapeutic outcome.

The feelings of fatigue, the mental fog, the changes in your body ∞ these are not isolated events. They are interconnected signals emerging from the deep biological systems that regulate your vitality. This knowledge is the first and most critical tool in your possession.

The path to hormonal balance and renewed function is a collaborative one. It involves a partnership between your lived experience and the objective data from clinical assessment. Consider this a starting point for a more informed and empowered conversation with a qualified clinician.

How might this understanding of your own metabolic signature shape the questions you ask? What possibilities open up when you view your health not as a series of problems to be fixed, but as a system to be understood and intelligently recalibrated? Your biology has a story to tell, and you are now better equipped to listen.