Fundamentals

Your biology tells a story. The intricate dance of hormones, the efficiency of your metabolism, the very code inscribed in your DNA ∞ these elements form the narrative of your health. When you seek to understand this story, whether through a hospital visit or a private wellness service, you generate data.

This information is more than a series of numbers on a page; it is a digital translation of your most personal physiological processes. The question of how this sensitive information is protected, managed, and utilized is central to your journey of health discovery.

The systems governing data in a traditional hospital setting and those in the emerging world of private wellness companies operate under distinctly different philosophies and regulations. Understanding these differences is the first step toward becoming a conscious steward of your own biological information.

In the established medical world, the handling of your health data is governed by a foundational piece of federal legislation ∞ the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, or HIPAA. This law creates a standardized framework for the protection of what is termed Protected Health Information, or PHI.

PHI includes any information in your medical record that can be used to identify you, from your name and birth date to your diagnoses, lab results, and treatment plans. The entities bound by HIPAA, known as “covered entities,” are your doctors, hospitals, clinics, and health insurance providers.

The law’s primary objective is to ensure the confidentiality and security of your data within the context of medical treatment, payment for services, and healthcare operations. It establishes a baseline of privacy, creating a secure container for the information generated when you are a patient within the healthcare system.

What Is the Core Principle of Hospital Data Protection?

The philosophy underpinning HIPAA is one of safeguarding information related to medical care. It grants you, the patient, a specific set of rights. You have the right to access your own medical records, to request corrections to them, and to receive a clear, written notice of how your information is being used.

A central tenet of the HIPAA Privacy Rule is the “minimum necessary” standard. This principle dictates that covered entities should only use or disclose the minimum amount of PHI necessary to accomplish a specific purpose. For instance, when a hospital bills an insurance company, it should only share the information required for that transaction, not your entire medical history.

This structure is designed to keep your health data tightly controlled and tethered to its original purpose ∞ facilitating your medical care and the administration of that care.

Your health information within the hospital system is protected by a federal law designed to secure data related to medical treatment and payment.

The private wellness sector operates within a different paradigm. Companies offering services like advanced hormone panels, genetic analysis, or personalized supplement plans are often not considered “covered entities” under HIPAA. Their relationship with you is defined not by a federal health mandate, but by the terms of service and privacy policy you agree to when you sign up for their service.

This is a commercial agreement. The data collected, which can be just as sensitive and comprehensive as that gathered in a hospital, is subject to the rules laid out in these documents. These companies are typically regulated by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which protects consumers from unfair or deceptive business practices, and a growing patchwork of state-level privacy laws.

This distinction creates two separate models for data governance. The hospital model, under HIPAA, is built around the concept of protecting data generated in the course of treating illness or injury. The private wellness model is built around a consumer relationship, where data is the key to providing a personalized product or service.

While leading companies in the wellness space have adopted voluntary best practices to build consumer trust, the foundational legal obligations differ significantly from the hospital environment. This divergence in governing principles has profound implications for how your biological story is read, shared, and preserved.

Intermediate

Advancing from a foundational awareness to an intermediate understanding requires a closer look at the operational mechanics of data handling in both hospital and private wellness settings. The divergence is not merely philosophical; it manifests in the day-to-day processes that dictate who can see your information, for what purpose, and with whom it can be shared.

The architecture of data flow in a hospital’s Electronic Health Record (EHR) system is fundamentally different from the data ecosystems built by direct-to-consumer wellness companies. These structural differences directly impact your control and the potential trajectory of your personal health information.

Within the hospital system, HIPAA’s Privacy Rule permits the use and disclosure of your Protected Health Information (PHI) without your explicit, case-by-case authorization for three main activities ∞ treatment, payment, and healthcare operations. Treatment encompasses the coordination and management of your care between doctors, nurses, specialists, and laboratories.

Payment involves the activities required to bill and collect for services, such as submitting claims to your insurer. Healthcare operations are the administrative, legal, and quality improvement activities necessary to run the healthcare organization.

These permissions are what allow a hospital to function efficiently, ensuring that a consulting physician can access your records or that the billing department can process your claim without requiring you to sign a new consent form at every step. Anything outside of these core functions, such as using your information for marketing purposes, requires your specific written authorization.

How Do Patient Rights Compare across Systems?

The rights afforded to you under HIPAA are robust and legally enforceable. They form a critical part of the patient-provider relationship. A direct comparison with the typical framework of a private wellness company reveals the distinct nature of each system. The wellness company’s obligations are defined by its own privacy policy and applicable consumer protection laws, which can vary in strength and scope.

| Right or Practice | Hospital System (Under HIPAA) | Private Wellness Company (Typical Model) |

|---|---|---|

| Governing Framework | The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). A federal law with civil and criminal penalties for violations. | Company’s Privacy Policy, Terms of Service, FTC regulations, and various state consumer privacy laws. |

| Right to Access Data | Legally enforceable right to inspect and obtain a copy of your medical records in a designated record set. | Generally provided, but governed by the company’s policy. The format and completeness may vary. |

| Right to Amend Data | You have the right to request an amendment to incorrect or incomplete information in your record. The entity must respond within a set timeframe. | Practices vary. Some companies may allow you to update account information, but amending core generated data (like genetic results) is typically not possible. |

| Data Sharing for Core Services | Permitted without specific authorization for treatment, payment, and healthcare operations under the “minimum necessary” standard. | Governed by broad consent to the privacy policy. Data is used to provide the service, for internal analytics, and to improve products. |

| Data Sharing with Third Parties | Requires your explicit written authorization for most disclosures outside of treatment, payment, and operations (e.g. for marketing). | May share or sell de-identified or aggregated data with research partners or other third parties if permitted by the privacy policy you agreed to. |

| Right to Deletion | Limited. A covered entity is not required to delete information from a medical record, as it is a legal document that must be maintained for a specific period. | Many companies offer a path to delete your account and data, though data already used in research may be impossible to retract. |

Private wellness companies, by contrast, operate on a consent-based model. When you purchase a hormone optimization package or a genetic ancestry test, you actively agree to the company’s privacy policy. This policy often grants the company broad permissions to use your data.

While the primary use is to deliver the service you purchased, the terms frequently include clauses that permit the use of your de-identified data for other purposes. De-identification is a process where overt identifiers like your name and address are removed from your data.

This de-identified data can then be aggregated with data from thousands of other users and used for internal research, to develop new products, or even be licensed or sold to external partners, such as pharmaceutical companies or academic researchers. Your initial consent is the gateway for these subsequent uses.

The hospital model limits data use to specific, defined functions unless you authorize otherwise, while the wellness model often relies on your upfront consent for a wider range of potential data applications.

This creates a critical distinction in the concept of data ownership and control. In the hospital system, the record is owned by the provider, but you retain a robust set of rights to control its use and disclosure.

In the private wellness system, by agreeing to the terms, you grant the company a license to use your data in ways specified by their policy. You may have the right to delete your account, but you often cannot retract the data that has already been incorporated into aggregated research datasets.

This structure positions your biological information not just as a record of your health, but as a valuable asset for research and development, an asset you provide access to when you click “I agree.”

- Protected Health Information (PHI) ∞ This is the specific term under HIPAA for individually identifiable health information held by covered entities. It is the data that the law is designed to protect.

- De-identified Data ∞ In the wellness sector, this refers to health data that has had personal identifiers removed. Companies often use this type of data for research, as it is subject to fewer restrictions than identifiable data.

- Informed Consent ∞ While this term is used in both contexts, its application differs. In a hospital, it often refers to consent for a specific procedure. In the wellness context, it refers to your agreement to a broad privacy policy that governs all subsequent uses of your data.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of the comparative data privacy practices between hospitals and private wellness companies requires moving beyond a simple regulatory comparison into the realms of bioethics, data economics, and cybersecurity. The fundamental difference lies in the conceptualization of the data itself.

Within the HIPAA framework, Protected Health Information (PHI) is positioned as an artifact of a clinical encounter, a component of a legal medical record whose protection is paramount to patient trust and safety.

In the private wellness ecosystem, user-generated biological data functions as a dual-purpose asset ∞ it is both the raw material for delivering a personalized consumer product and a valuable, scalable commodity for secondary markets. This distinction in the economic and ethical status of the data shapes every aspect of its governance.

The Commodification of the Personal Biomarker

The business model of many direct-to-consumer (DTC) wellness companies is predicated on the value of aggregated biological data. While the initial transaction involves a fee for a specific analysis, such as a hormone panel or a genomic sequence, the long-term value proposition for the company often resides in the creation of massive, proprietary datasets.

These databases, when stripped of direct identifiers, become powerful tools for machine learning, drug discovery, and population-level health research. Pharmaceutical companies and academic institutions may pay significant sums for access to this information, as it provides a rich resource for identifying novel therapeutic targets or understanding the genetic underpinnings of disease. Your consent, embedded within the terms of service, is the legal mechanism that facilitates this transformation of your personal biological information into a commercial research asset.

This model stands in stark contrast to the hospital environment. While de-identified hospital data is also used for research, the process is typically governed by Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) and the HIPAA Privacy Rule’s specific provisions for research.

These provisions require either patient authorization or a waiver of authorization from an IRB, which must determine that the research poses minimal risk to patient privacy. The commercial incentive structure is different; the primary mission of the hospital is patient care, with research being a secondary, albeit vital, function. For many wellness companies, the collection and subsequent monetization of data is a primary operational goal, co-equal with the delivery of the initial consumer service.

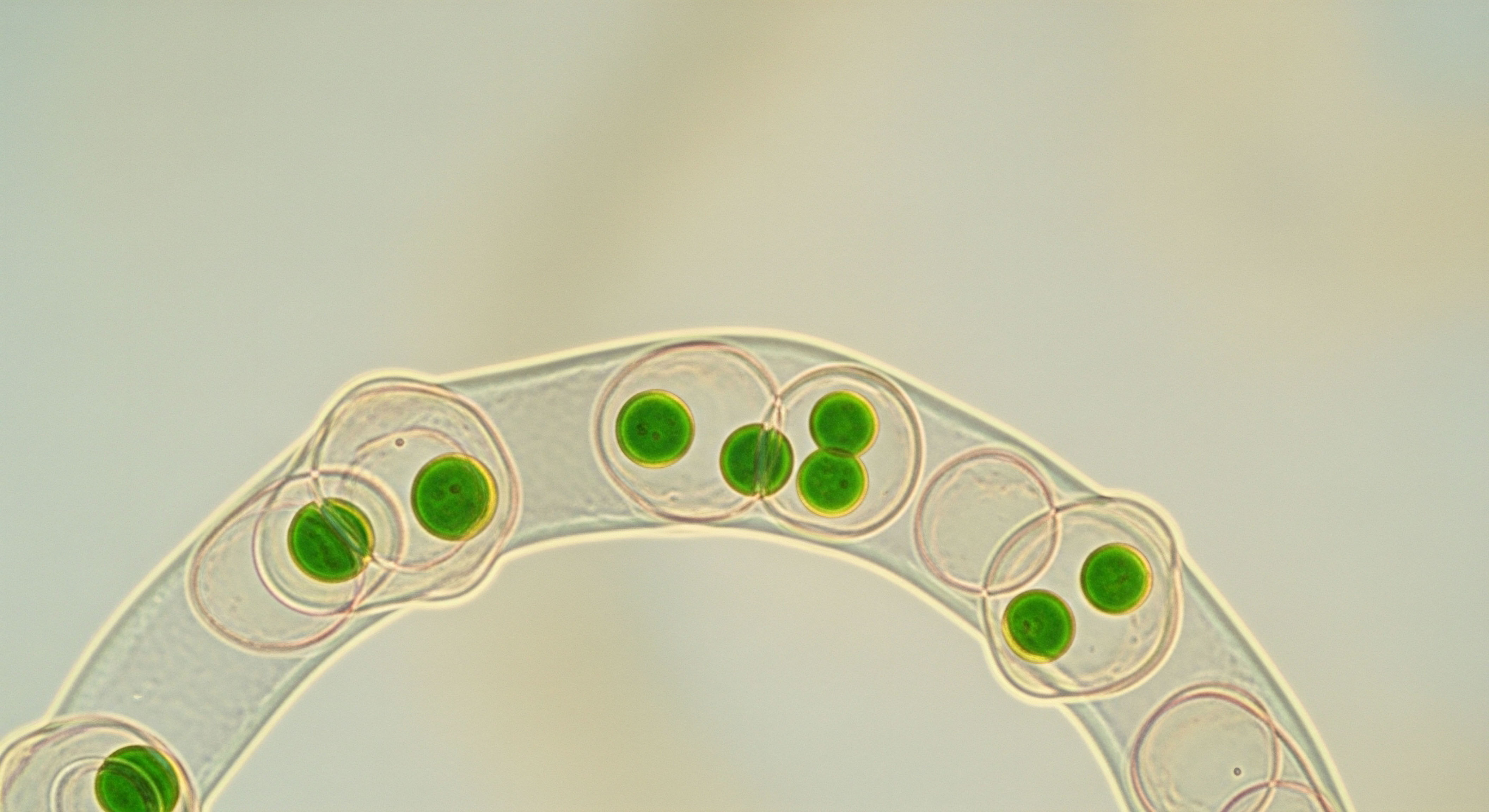

Can De-Identified Biological Data Truly Be Anonymous?

A critical point of academic debate centers on the efficacy of data de-identification, particularly for rich biological datasets containing hormonal and genetic information. The process of removing direct identifiers (name, address, social security number) as stipulated by the HIPAA Safe Harbor method may be insufficient to guarantee anonymity.

A person’s genomic sequence, for example, is inherently identifiable. Researchers have demonstrated that by cross-referencing supposedly anonymous genetic data with publicly available information, such as genealogical databases or voter rolls, re-identification is possible. This has profound implications for privacy, as it could expose not only the individual but also their biological relatives to unwanted scrutiny.

The very nature of comprehensive biological data, especially genetic information, challenges the traditional concept of de-identification, raising complex ethical questions about long-term privacy risks.

The data collected during a personalized wellness protocol, such as Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) or peptide therapy, presents a similar challenge. A detailed longitudinal record of specific hormone levels, metabolic markers, and prescribed compounds creates a unique physiological signature that could also be vulnerable to re-identification through advanced analytics.

| Data Point in a Wellness Protocol | Description | Potential for Re-identification |

|---|---|---|

| Full Genetic Sequence | The complete DNA makeup of an individual. | High. Inherently unique and can be cross-referenced with public databases to identify individuals and their relatives. |

| Longitudinal Hormone Levels | Regular measurements of Testosterone, Estradiol, SHBG, LH, FSH over time. | Moderate to High. A unique pattern of hormonal fluctuation and response to therapy creates a distinct “fingerprint.” |

| Specific Peptide Protocol | Use of compounds like Sermorelin, Ipamorelin, or PT-141. | Moderate. The specific combination and timing of less common therapies can contribute to a unique user profile. |

| Continuous Glucose Monitoring Data | A dense stream of blood glucose readings over days or weeks. | Moderate to High. Individual metabolic responses to food and activity are highly personalized and create a unique data signature. |

| Microbiome Analysis | Composition of an individual’s gut bacteria. | High. Research suggests the human microbiome is unique enough to be used as a forensic identifier. |

Regulatory Gaps and the Path Forward

The current regulatory landscape was not designed for the era of big data and personalized wellness. HIPAA was enacted before the widespread adoption of the internet and long before consumer genomics became a billion-dollar industry. Its focus on “covered entities” leaves a significant portion of the health data ecosystem, including wellness apps, wearables, and DTC testing companies, outside its direct purview.

While laws like the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) offer protections against the use of genetic information by health insurers and employers, they do not cover its use for life, disability, or long-term care insurance. Furthermore, they do not restrict the way companies collect, use, and share this information for research or marketing.

The resulting regulatory patchwork creates ambiguity and potential risk for individuals seeking to proactively manage their health. As personalized medicine advances, the line between clinical care and wellness optimization will continue to blur. This evolution necessitates a new conversation about data governance, one that may require a harmonization of principles from both the HIPAA and consumer protection worlds.

Future frameworks may focus less on who is holding the data and more on the sensitivity of the data itself, applying consistent, robust protections for all biological information, regardless of whether it was generated in a hospital or purchased online. This approach would ensure that as you take ownership of your health narrative, the very data that constitutes that story remains unequivocally yours to control.

- Institutional Review Board (IRB) ∞ A committee that reviews and monitors biomedical and behavioral research involving human subjects. An IRB has the authority to approve, require modifications in, or disapprove research, serving as an important ethical oversight body.

- Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) ∞ A federal law that protects individuals from genetic discrimination in health insurance and employment. It has notable limitations and does not apply to other forms of insurance.

- Data Triangulation ∞ The process of combining different data sources to produce a more complete picture. In the context of privacy, it is the method by which de-identified data can be cross-referenced with other datasets to re-identify an individual.

References

- Nass, Sharyl J. et al. editors. Beyond the HIPAA Privacy Rule ∞ Enhancing Privacy, Improving Health Through Research. National Academies Press, 2009.

- Gostin, Lawrence O. and James G. Hodge Jr. “Personal Privacy and Common Goods ∞ A Framework for Balancing in Public Health.” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 101, no. S1, 2011, pp. S311-S316.

- Hazel, J. W. & Slobogin, C. “Who Knows What, and When? ∞ A Survey of the Privacy Policies Proffered by U.S. Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Testing Companies.” Journal of Law and the Biosciences, vol. 5, no. 2, 2018, pp. 257-283.

- Majumder, Mary A. et al. “Privacy in Consumer Genetic Testing ∞ A Public Statement from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics.” Genetics in Medicine, vol. 23, no. 8, 2021, pp. 1425-1427.

- Annas, George J. “HIPAA Regulations ∞ A New Era of Medical-Record Privacy?” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 348, no. 15, 2003, pp. 1486-1490.

- McGuire, Amy L. and Richard A. Gibbs. “No Longer De-Identified.” Science, vol. 312, no. 5772, 2006, p. 370.

- Ness, Roberta B. “Influence of the HIPAA Privacy Rule on Health Research.” JAMA, vol. 298, no. 18, 2007, pp. 2164-2170.

Reflection

The Stewardship of Your Biological Narrative

You have now traversed the distinct landscapes of data governance that define modern health and wellness. You have seen the structured, regulated fortress of the hospital system and the dynamic, consent-driven marketplace of private wellness. The knowledge of how your biological story is recorded, protected, and utilized is itself a form of power. It transforms you from a passive subject into an active participant in your own health journey. This understanding is the critical first instrument in your toolkit.

The path toward reclaiming vitality and function is deeply personal. It involves choices not only about protocols and treatments but also about trust and information. As you move forward, consider the nature of the data you share. See it not as an abstract collection of files, but as a living extension of your own physiology.

Each data point is a word, each lab panel a sentence, and each longitudinal report a chapter in your unique biological narrative. Who do you entrust to be the custodian of this story? What uses of this narrative align with your personal values and goals?

The answers to these questions are as individual as your own genetic code. The journey ahead is one of continued learning, conscious decision-making, and the profound realization that you are the ultimate author of your own well-being.