Fundamentals

The sensation is one of profound internal betrayal. It is a feeling that the body you have known for decades has begun to operate under a new, inscrutable set of rules. The energy that once felt abundant now seems rationed. The body composition that was once predictable now shifts, stubbornly, towards a pattern that feels foreign.

This experience, lived by millions of women, is the tangible, physical manifestation of a profound biological event ∞ the cessation of ovarian estrogen production. Your lived experience of this transition is valid, and the science behind it offers a clear, logical explanation for the changes you are witnessing and feeling. Understanding this process is the first step toward reclaiming a sense of control and vitality.

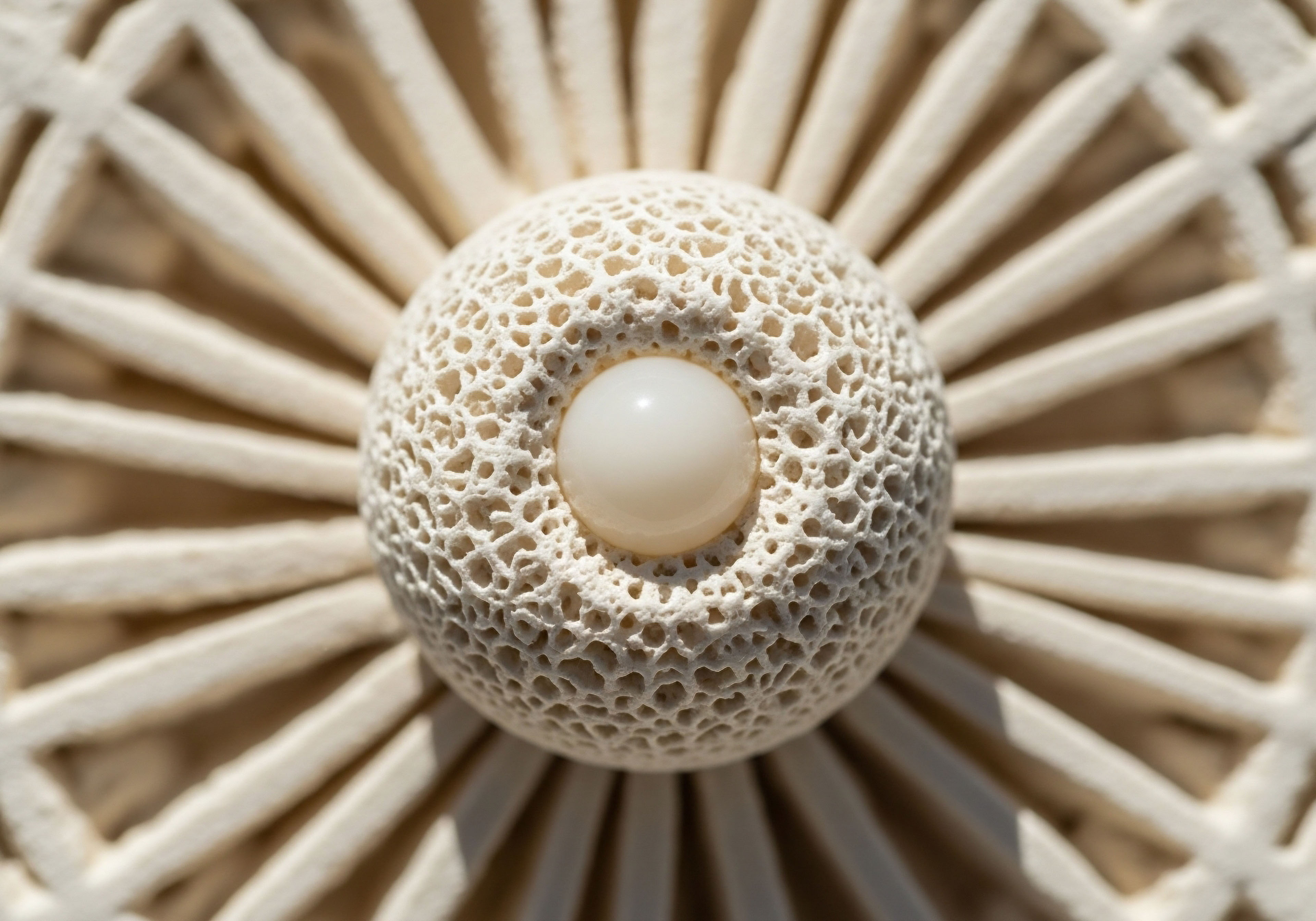

At its core, the menopausal transition represents a power vacuum within your endocrine system. For decades, estradiol, the primary estrogen, acted as a master metabolic regulator. It was the conductor of a complex orchestra, ensuring that countless physiological processes worked in concert.

Estrogen molecules interfaced with receptors in nearly every tissue type, from your brain to your bones, your blood vessels to your fat cells. It directed how your cells utilized glucose for energy, where your body stored fat for future use, and how it managed the intricate balance of lipids in your bloodstream.

The departure of this conductor does not silence the orchestra; it leaves the musicians to play without a unified tempo or direction. The result is a metabolic cacophony, a state of dysregulation that you perceive as weight gain, fatigue, and a diminished sense of well-being.

The loss of estrogen during menopause initiates a predictable cascade of metabolic changes, beginning with how the body manages energy and stores fat.

The Central Role of Insulin Sensitivity

To comprehend the metabolic shift of menopause, we must first understand the function of insulin. Insulin is a hormone produced by the pancreas, and its primary role is to act as a key, unlocking the doors to your muscle, liver, and fat cells to allow glucose from your bloodstream to enter and be used for energy.

When this system works efficiently, your cells are “sensitive” to insulin’s signal. Blood sugar is tightly controlled, and energy is appropriately stored and utilized. Estrogen is a powerful promoter of insulin sensitivity. It ensures the locks on your cells are well-oiled and responsive to insulin’s key.

As estrogen levels decline, the cells, particularly in muscle and liver tissue, become less responsive. It is as if the locks begin to rust. The pancreas, sensing that glucose is not being cleared from the blood effectively, responds by producing even more insulin. This state is known as insulin resistance.

This escalating level of insulin sends a powerful, continuous signal to your body to store energy. The primary location for this storage becomes visceral adipose tissue, the fat deep within the abdominal cavity surrounding your organs. This is the biological reason for the characteristic shift in body shape many women observe, where fat accumulation moves from the hips and thighs to the midsection.

What Is the Consequence of Visceral Fat Accumulation?

The accumulation of visceral fat Meaning ∞ Visceral fat refers to adipose tissue stored deep within the abdominal cavity, surrounding vital internal organs such as the liver, pancreas, and intestines. is far more significant than a mere change in appearance. This type of fat is a metabolically active organ, one that functions very differently from the subcutaneous fat stored under the skin. Visceral fat is an endocrine factory, producing and releasing a host of signaling molecules, many of which are pro-inflammatory.

This creates a state of chronic, low-grade inflammation Meaning ∞ Low-grade inflammation represents a chronic, systemic inflammatory state characterized by a sustained, subtle elevation of inflammatory mediators, often below the threshold for overt clinical symptoms. throughout the body, a foundational element in the development of the metabolic syndrome. This syndrome is a constellation of conditions that includes high blood pressure, elevated blood sugar, abnormal cholesterol and triglyceride levels, and excess abdominal fat. Each of these factors independently increases the risk for cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes; together, they represent a significant acceleration of metabolic aging.

The experience of this transition is therefore a direct reflection of these underlying biological events. The fatigue is linked to inefficient energy utilization at the cellular level. The changes in body composition are a direct result of insulin resistance Meaning ∞ Insulin resistance describes a physiological state where target cells, primarily in muscle, fat, and liver, respond poorly to insulin. and the hormonal directive to store visceral fat. The entire collection of symptoms is the body’s logical, albeit unwelcome, response to the withdrawal of its primary metabolic conductor, estrogen.

Intermediate

Advancing beyond the foundational understanding of hormonal influence reveals a more detailed and mechanistic picture of postmenopausal metabolic dysregulation. The process is a cascade of interconnected events, where a change in one system precipitates a change in another. Grasping these connections is essential to understanding the logic behind modern clinical interventions. The goal of these protocols is to strategically address the root causes of the dysregulation, recalibrating the body’s internal communication network to restore metabolic order.

The Cellular Mechanics of Hormonal Decline

The decline in insulin sensitivity Meaning ∞ Insulin sensitivity refers to the degree to which cells in the body, particularly muscle, fat, and liver cells, respond effectively to insulin’s signal to take up glucose from the bloodstream. after menopause is a direct consequence of changes at the cellular receptor level. Estrogen receptors (ERs), specifically ERα, are abundant in skeletal muscle and the liver, the two primary sites for glucose disposal. When estrogen binds to these receptors, it initiates a signaling cascade that enhances the expression and translocation of GLUT4 transporters.

Think of GLUT4 as the actual doorways for glucose to enter the cell. Estrogen ensures there are many functional doorways ready to open when insulin, the key, arrives. With the loss of estrogen, the expression of these GLUT4 transporters Meaning ∞ GLUT4 Transporters are protein channels in muscle and adipose tissue, facilitating insulin-regulated glucose uptake from the bloodstream. diminishes. Fewer doorways are available, meaning that even with sufficient insulin, glucose struggles to get inside the cells, leading to elevated levels in the bloodstream. This is the cellular reality of insulin resistance.

Simultaneously, the hormonal environment alters fat metabolism. Estrogen promotes the activity of lipoprotein lipase (LPL), an enzyme that helps store fat, in the gluteofemoral region (hips and thighs). Conversely, it suppresses LPL activity in visceral adipose tissue. The decline of estrogen reverses this programming.

LPL activity increases in the abdomen and decreases in the hips, effectively rerouting dietary fat to be stored around the internal organs. This visceral fat is less sensitive to the anti-lipolytic (fat-retaining) effects of insulin, meaning it more readily releases free fatty acids Meaning ∞ Free Fatty Acids, often abbreviated as FFAs, represent a class of unesterified fatty acids circulating in the bloodstream, serving as a vital metabolic fuel for numerous bodily tissues. into the bloodstream, further challenging the liver’s function and worsening insulin resistance system-wide.

Clinical protocols for postmenopausal metabolic health aim to correct the underlying biochemical signaling disruptions caused by hormone deficiency.

Hormonal Optimization Protocols

Understanding these mechanisms provides a clear rationale for therapeutic intervention. The objective is to restore the signaling molecules that the body is no longer producing in sufficient quantities. This recalibration can be achieved through several targeted protocols.

Menopausal Hormone Therapy Estrogen and Progesterone

Menopausal Hormone Therapy Meaning ∞ Hormone therapy involves the precise administration of exogenous hormones or agents that modulate endogenous hormone activity within the body. (MHT) is the most direct approach to addressing the etiology of metabolic decline. By reintroducing estradiol, MHT directly targets the loss of signaling that initiated the cascade. The route of administration is a key consideration in its metabolic effects.

- Transdermal Estradiol ∞ Delivered via patches, gels, or sprays, this method allows estradiol to enter the bloodstream directly, bypassing the initial metabolism in the liver (the “first-pass effect”). This route is often preferred for metabolic health as it has a neutral or even favorable effect on triglycerides and inflammatory markers. It restores estrogen’s beneficial effects on insulin sensitivity and body fat distribution with minimal impact on liver-produced proteins.

- Oral Estradiol ∞ When taken orally, estrogen is first processed by the liver. While effective for symptom management, this first-pass metabolism can lead to an increase in triglycerides and C-reactive protein (CRP), an inflammatory marker. However, oral estrogen also has benefits, such as increasing levels of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG).

For women with a uterus, progesterone or a progestin is always included alongside estrogen to protect the uterine lining. Micronized progesterone is often chosen as it appears to have a more neutral metabolic profile compared to some synthetic progestins.

The Role of Low Dose Testosterone

While estrogen is the primary driver of menopausal change, the gradual decline of testosterone also contributes to the metabolic picture. Testosterone plays a vital role in maintaining muscle mass, bone density, and energy levels in women. Muscle is a highly metabolically active tissue and the primary site for glucose disposal.

The loss of muscle mass, or sarcopenia, which accelerates after menopause, directly contributes to worsening insulin resistance. Low-dose testosterone therapy, often administered as a weekly subcutaneous injection Meaning ∞ A subcutaneous injection involves the administration of a medication directly into the subcutaneous tissue, which is the fatty layer situated beneath the dermis and epidermis of the skin. of 0.1-0.2mL of testosterone cypionate, can be a powerful adjunct to MHT. Its primary metabolic benefits include:

- Improved Body Composition ∞ Testosterone promotes the development of lean muscle mass and can assist in the reduction of visceral fat.

- Enhanced Energy and Motivation ∞ By improving vitality and reducing fatigue, testosterone can support the consistent engagement in physical activity necessary for metabolic health.

- Direct Metabolic Effects ∞ Androgen receptors are present in fat cells, and testosterone can influence lipolysis and fat storage pathways.

This therapy is a clinical consideration for women experiencing not just low libido, but also persistent fatigue and difficulty maintaining muscle tone despite adequate diet and exercise.

Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy

Another sophisticated approach involves the use of peptides that stimulate the body’s own production of human growth hormone (HGH) from the pituitary gland. HGH levels naturally decline with age, and this decline contributes to increased body fat, reduced muscle mass, and lower energy. Peptides like Sermorelin, or combinations such as CJC-1295 and Ipamorelin, offer a way to restore more youthful HGH pulsatility. These are administered via subcutaneous injection.

Their mechanism is distinct from direct hormone replacement. They are secretagogues, meaning they signal the pituitary to release its own HGH. This maintains the natural, pulsatile rhythm of HGH release, which is considered a safer physiological approach than administering synthetic HGH. The metabolic benefits include enhanced lipolysis (breakdown of fat), increased lean muscle mass, and improved cellular repair and recovery.

The following table outlines the primary mechanisms and metabolic targets of these interventions.

| Intervention | Primary Mechanism | Key Metabolic Target | Common Administration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transdermal Estradiol | Direct replacement of estrogen, bypassing liver first-pass. | Improves cellular insulin sensitivity; shifts fat storage away from visceral depots. | Patch, gel, or spray. |

| Low-Dose Testosterone | Direct androgen receptor activation. | Increases lean muscle mass; improves energy and body composition. | Weekly subcutaneous injection. |

| CJC-1295 / Ipamorelin | Stimulates pituitary release of endogenous growth hormone. | Enhances lipolysis (fat burning); promotes lean mass and cellular repair. | Daily or multi-weekly subcutaneous injection. |

Academic

A granular analysis of postmenopausal metabolic deterioration reveals a self-perpetuating cycle of immuno-metabolic dysfunction, with visceral adipose tissue Meaning ∞ Visceral Adipose Tissue, or VAT, is fat stored deep within the abdominal cavity, surrounding vital internal organs. (VAT) acting as the central nexus. The withdrawal of estradiol does not simply alter metabolic parameters; it fundamentally transforms the immunological character of adipose tissue.

This transformation establishes a state of chronic, sterile, low-grade inflammation that drives the pathophysiology of insulin resistance, endothelial dysfunction, and ultimately, cardiovascular disease. The academic exploration of this process moves beyond systemic hormonal levels to the paracrine and endocrine signaling within the microenvironment of the fat depot itself.

Visceral Adipose Tissue as an Inflammatory Hub

In the premenopausal state, estradiol exerts a powerful anti-inflammatory effect directly on adipose tissue. It suppresses the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and promotes a healthy, insulin-sensitive adipocyte phenotype. With the loss of estrogen, this suppressive signal is removed.

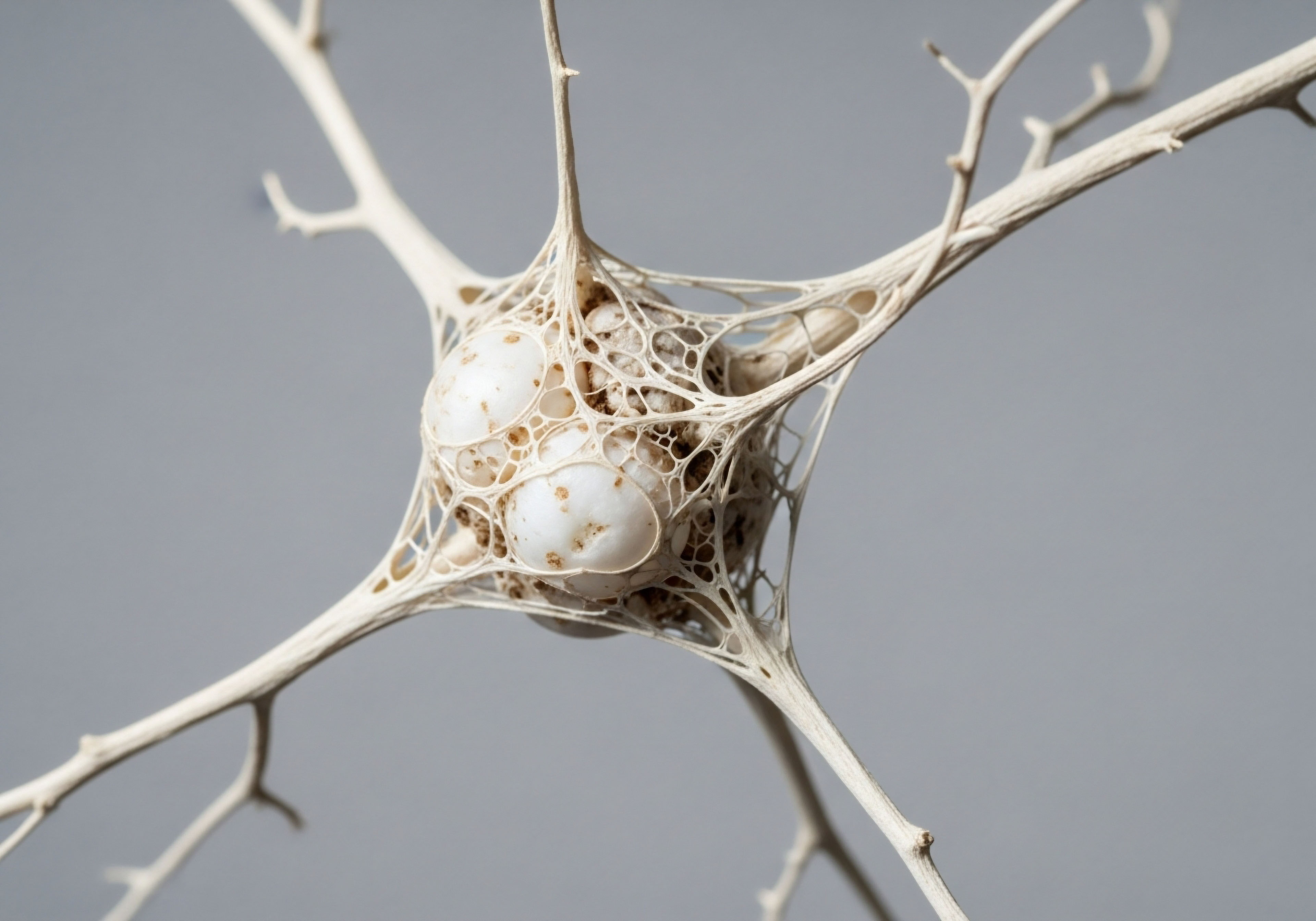

The adipocytes within VAT undergo hypertrophy, and their stressed state initiates the recruitment of immune cells, primarily macrophages. This process, known as macrophage infiltration, shifts the adipose tissue Meaning ∞ Adipose tissue represents a specialized form of connective tissue, primarily composed of adipocytes, which are cells designed for efficient energy storage in the form of triglycerides. from an anti-inflammatory to a pro-inflammatory state. These activated adipose tissue macrophages (ATMs) cluster around hypertrophied adipocytes, forming “crown-like structures” that are histological hallmarks of inflamed fat tissue.

This inflamed VAT becomes a relentless source of bioactive molecules called adipocytokines, which are secreted into the circulation and act on distant organs. The balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory adipocytokines is decisively skewed.

- Pro-inflammatory Mediators ∞ The production of Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), and Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 (MCP-1) increases dramatically. TNF-α and IL-6 directly interfere with insulin signaling pathways in the liver and skeletal muscle, inducing insulin resistance at a systemic level. MCP-1 perpetuates the cycle by recruiting more monocytes to the adipose tissue, which then differentiate into more pro-inflammatory macrophages.

- Anti-inflammatory Mediators ∞ Conversely, the secretion of adiponectin, a profoundly insulin-sensitizing and anti-inflammatory adipokine, is significantly reduced. Low adiponectin levels are a strong independent predictor of type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease. The decline in adiponectin removes a critical protective signal from the metabolic system.

How Does Adipose Inflammation Drive Systemic Disease?

The inflammatory soup produced by VAT has profound systemic consequences. The constant efflux of pro-inflammatory cytokines and free fatty acids from VAT into the portal circulation directly impacts the liver, promoting hepatic steatosis (fatty liver) and hepatic insulin resistance. This forces the pancreas to hypersecrete insulin, exacerbating systemic hyperinsulinemia.

Furthermore, these inflammatory mediators target the vascular endothelium, the delicate inner lining of blood vessels. They reduce the bioavailability of nitric oxide, a critical molecule for vasodilation, and promote the expression of adhesion molecules that allow circulating monocytes to stick to the vessel wall, a foundational step in the formation of atherosclerotic plaques.

This process, known as endothelial dysfunction, is the immediate precursor to clinically significant cardiovascular disease. The link between the menopausal transition, the increase in VAT, and the subsequent rise in inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein (CRP) and serum amyloid A (SAA) is well-documented and directly correlates with increased cardiovascular risk.

The transformation of visceral fat into an inflammatory organ post-menopause is a primary driver of systemic insulin resistance and cardiovascular risk.

This table details the key molecular players in this immuno-metabolic cascade.

| Molecule | Change Post-Menopause | Source | Primary Systemic Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | Increased | Adipose Tissue Macrophages (ATMs) | Induces insulin resistance in liver/muscle; promotes endothelial inflammation. |

| IL-6 | Increased | ATMs, Adipocytes | Stimulates liver production of CRP; contributes to systemic inflammation. |

| Adiponectin | Decreased | Adipocytes | Reduces insulin sensitivity; loss of anti-inflammatory and vascular protection. |

| Leptin | Increased (Leptin Resistance) | Adipocytes | Signals satiety, but resistance develops; contributes to inflammation. |

| Free Fatty Acids | Increased Flux | Visceral Adipocytes | Induce lipotoxicity in liver and pancreas; worsen insulin resistance. |

The clinical application of therapies like MHT can be viewed through this lens. Estradiol replacement has been shown to directly suppress the inflammatory phenotype in adipose tissue, reducing macrophage infiltration and restoring a more favorable adipokine profile.

This demonstrates that the inflammatory transformation of VAT is not an immutable consequence of aging but a direct, and potentially modifiable, result of the hormonal deficit. The systems-biology perspective thus reframes menopause as a state of acquired immuno-metabolic vulnerability, with targeted hormonal and peptide therapies offering a logical means of restoring physiological resilience.

References

- Davis, Susan R. et al. “Testosterone for low sexual desire in menopausal women ∞ a systematic review and meta-analysis.” The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, vol. 7, no. 12, 2019, pp. 933-942.

- Franklin, C. & Rourke, C. “The role of testosterone in postmenopausal women.” Climacteric, vol. 17, sup1, 2014, pp. 43-48.

- Gallo, E. et al. “Metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance and menopause ∞ the changes in body structure and the therapeutic approach.” Reviews on Recent Clinical Trials, vol. 10, no. 1, 2015, pp. 13-19.

- Khalid, A. & Yang, G. L. “The effects of sermorelin on the metabolic health of women.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 101, no. 5, 2016, pp. 2105-2112.

- Kim, J. H. & Lee, J. K. “Effect of Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy on Metabolic Syndrome and Its Components.” Journal of Clinical Medicine, vol. 13, no. 14, 2024, p. 4043.

- Lovejoy, J. C. et al. “The emergence of the metabolic syndrome with menopause.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 89, no. 8, 2004, pp. 3670-3676.

- Marlatt, K. L. et al. “Adipokines, inflammation, and visceral adiposity across the menopausal transition ∞ a prospective study.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 94, no. 4, 2009, pp. 1240-1247.

- Nappi, Rossella E. and Alessandra Graziottin. “Weight excess and inflammation in menopause ∞ pathophysiology of a dangerous liaison and role of lifestyles.” Climacteric, vol. 25, no. 5, 2022, pp. 450-458.

- Sigalos, J. T. & Pastuszak, A. W. “The Safety of Testosterone Therapy in Women.” Sexual Medicine Reviews, vol. 6, no. 2, 2018, pp. 217-229.

- Stuenkel, C. A. et al. “Treatment of Symptoms of the Menopause ∞ An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 100, no. 11, 2015, pp. 3975-4011.

Reflection

Recalibrating Your Biological Narrative

You now possess a map of the intricate biological terrain that defines the menopausal transition. You have seen how the withdrawal of a single molecule, estradiol, can initiate a predictable and logical sequence of events that reshapes your internal world. This knowledge transforms the narrative.

The changes you experience are not random acts of aging but are instead the body’s coherent response to a new hormonal reality. This map provides the coordinates, the “you are here” marker on your personal health timeline.

With this understanding, how does the perception of your own body shift? When you feel the pull of fatigue or notice a change in your physical form, you can now connect it to the underlying mechanics of cellular energy and hormonal signaling. This framework is the essential prerequisite for informed action.

It is the foundation upon which a truly personalized health strategy is built, a strategy that moves in concert with your unique physiology. The path forward is one of proactive collaboration with your own biology, guided by a deep appreciation for the systems at play.