Fundamentals

The sensation is undeniable. It is a shift in the very architecture of your body, a change in the way you carry weight, and a subtle but persistent alteration in your energy. You may feel that your metabolism, once a reliable furnace, now operates on a lower, more sluggish setting.

This experience, common to so many women navigating the menopausal transition, is a direct reflection of a profound internal recalibration. Your body is responding to a new set of biological instructions, and understanding this process is the first step toward reclaiming your sense of vitality.

The changes you are feeling are not a matter of willpower; they are a matter of physiology. They originate deep within your endocrine system, the body’s intricate communication network, which for decades has been orchestrated by the rhythmic rise and fall of specific hormonal signals.

At the center of this transition is the diminishing production of estrogen by the ovaries. For years, estrogen has performed a multitude of roles beyond its reproductive functions. It has acted as a master metabolic regulator, influencing how your cells utilize glucose for energy, where your body stores fat, and how your tissues respond to insulin.

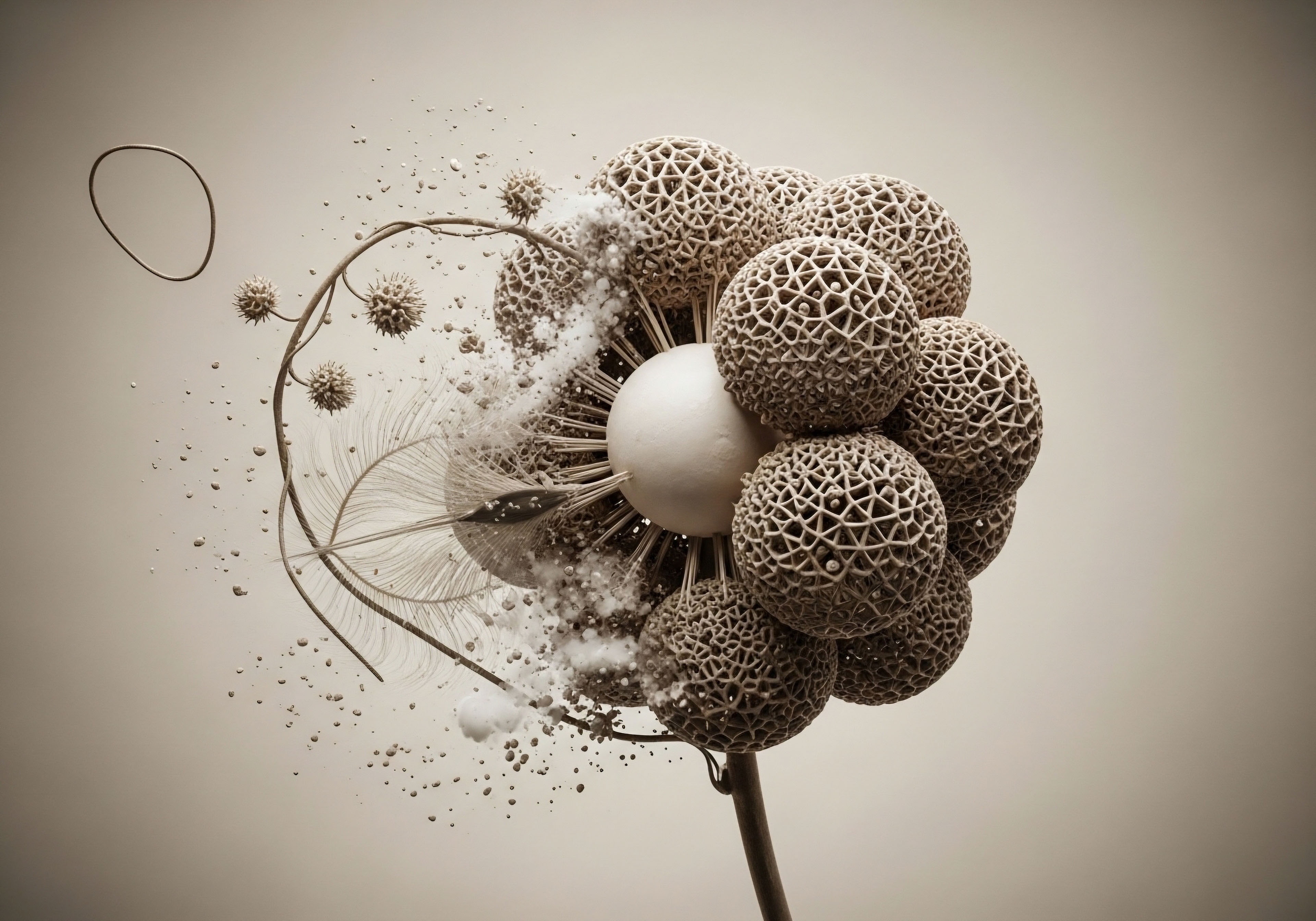

The decline in estrogen signals a systemic change, prompting a redistribution of adipose tissue. Fat storage patterns tend to move from the hips and thighs to the abdominal area. This visceral fat, packed around your internal organs, is metabolically active in a way that subcutaneous fat is not, releasing inflammatory signals that further disrupt metabolic balance. This is the biological reality behind the changes many women observe in their physique during this time.

The decline in estrogen during menopause directly alters the body’s fat storage patterns, shifting it toward the abdomen and impacting metabolic function.

This hormonal shift forms the foundation of the metabolic changes experienced during menopause. Your body’s response is a logical, programmed adaptation to a new internal environment. By understanding the key hormonal players and their roles, you can begin to see your body’s current state as a system in transition, one that can be supported and guided toward a new equilibrium.

This knowledge empowers you to move from a place of concern to a position of informed action, working with your biology to foster metabolic health for the long term.

The Primary Hormonal Architects of Metabolic Function

Three primary hormones orchestrate the symphony of female metabolic health ∞ estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone. While often discussed in the context of reproduction, their influence extends to every cell in the body, governing energy, mood, and body composition. During the menopausal transition, the fluctuating and eventual decline of these hormones creates a new biochemical landscape that your body must learn to navigate.

Estrogen the Master Regulator

Estrogen, specifically estradiol (E2), is a powerful metabolic conductor. It enhances insulin sensitivity, meaning it helps your cells efficiently take up glucose from the bloodstream for energy. This process keeps blood sugar levels stable and prevents the excess glucose from being stored as fat.

Estrogen also plays a direct role in regulating lipid metabolism, helping to maintain healthy levels of cholesterol. Its decline is a primary driver of the metabolic challenges of menopause, including increased insulin resistance and a shift in cholesterol profiles. The body, in response to lower estrogen, seeks to find a new metabolic steady state, a process that can manifest as weight gain and changes in energy.

Progesterone the Calming Counterpart

Progesterone works in concert with estrogen, and its decline also contributes to the menopausal experience. It has a calming effect on the nervous system, which can promote better sleep. Quality sleep is a cornerstone of metabolic health, as sleep deprivation is linked to increased cortisol levels and insulin resistance. The loss of progesterone can therefore indirectly affect metabolism by disrupting sleep patterns and contributing to stress, both of which can encourage fat storage and make weight management more difficult.

Testosterone the Anabolic Force

Though present in smaller quantities in women than in men, testosterone is vital for maintaining muscle mass, bone density, and metabolic rate. Muscle is a metabolically active tissue, meaning it burns calories even at rest. The age-related decline in testosterone, which accelerates during menopause, can lead to a loss of lean muscle mass, a condition known as sarcopenia.

This reduction in muscle tissue lowers the body’s overall metabolic rate, meaning fewer calories are needed to maintain the same weight. Supporting healthy testosterone levels is therefore a key aspect of maintaining a robust metabolism throughout the aging process.

The Central Command System the HPG Axis

These hormones do not operate in isolation. They are part of a sophisticated feedback loop known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. Think of this as the central command system for your reproductive and hormonal health. The hypothalamus in the brain releases Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH), which signals the pituitary gland to release Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH).

These hormones, in turn, travel to the ovaries and stimulate the production of estrogen and progesterone. During perimenopause, the ovaries become less responsive to LH and FSH. The brain, sensing low estrogen levels, sends out more and more FSH in an attempt to stimulate the ovaries.

This is why elevated FSH is a key marker of the menopausal transition. The eventual cessation of ovarian estrogen production marks the completion of this shift. Understanding this central mechanism reveals that menopause is a systemic event, orchestrated by the brain, that has profound effects on the entire body’s metabolic machinery.

Intermediate

The metabolic shifts experienced during menopause are rooted in specific, measurable changes at the cellular level. As estrogen levels decline, the intricate machinery that governs how your body processes and stores energy is fundamentally altered. This process is centered around the concept of insulin resistance, a state where the body’s cells become less responsive to the hormone insulin.

Understanding this mechanism provides a clear, scientific explanation for the weight gain, particularly around the midsection, and the increased risk for metabolic conditions that can accompany this life stage. It is a biological cascade, where one hormonal change triggers a series of metabolic consequences.

Estrogen directly facilitates the action of insulin. It helps to ensure that when you consume carbohydrates, the resulting glucose in your bloodstream is efficiently transported into your muscle and liver cells to be used for energy or stored as glycogen for later use. When estrogen levels fall, this process becomes less efficient.

The pancreas compensates by producing more insulin to try and force the cells to respond. This state of high insulin levels, known as hyperinsulinemia, is a hallmark of insulin resistance. Chronically elevated insulin sends a powerful signal to the body to store excess energy as fat, especially in the abdominal region.

This visceral adipose tissue (VAT) is not merely a passive storage depot; it is an active endocrine organ that secretes its own set of hormones and inflammatory molecules, further perpetuating a cycle of metabolic dysregulation.

The Clinical Manifestation of Hormonal Decline

The downstream effects of this estrogen-driven insulin resistance are observable and measurable. They represent a shift away from the metabolic profile of the premenopausal years and toward a pattern that requires a more conscious and targeted approach to health management. These clinical manifestations are interconnected, each one influencing the others in a complex web of metabolic interactions.

Increased Visceral Adipose Tissue

The most visible sign of menopausal metabolic change is often the accumulation of visceral fat. Estrogen promotes fat storage in the hips, thighs, and buttocks (gluteofemoral fat), which is less metabolically harmful. With the loss of estrogen, the body begins to favor fat deposition around the internal organs in the abdomen.

This visceral fat is strongly linked to an increased risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease because of the inflammatory substances it releases. This change in body composition is a direct result of the hormonal shift, explaining why many women find it difficult to lose weight from their midsection despite consistent diet and exercise efforts.

Dyslipidemia an Altered Cholesterol Profile

Estrogen helps to maintain a favorable lipid profile by supporting higher levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL), the “good” cholesterol, and lower levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL), the “bad” cholesterol. As estrogen declines, this balance can shift. Many women will see a rise in their LDL and triglyceride levels, and a decrease in their HDL levels during and after menopause.

This condition, known as dyslipidemia, is a significant risk factor for the development of atherosclerosis, the buildup of plaque in the arteries. This is a key reason why cardiovascular risk increases for women after menopause.

Sarcopenia and Reduced Metabolic Rate

The decline in both estrogen and testosterone contributes to the gradual loss of muscle mass. Since muscle is a primary site of glucose disposal and a major contributor to the body’s resting metabolic rate, losing muscle has a twofold negative effect. First, with less muscle, there are fewer places for glucose to go, which can worsen insulin resistance.

Second, a lower metabolic rate means the body burns fewer calories at rest, making it easier to gain weight even if caloric intake remains the same. Preserving and building lean muscle mass is therefore a critical strategy for combating menopausal metabolic changes.

Clinical Protocols for Metabolic Recalibration

Addressing these metabolic shifts requires a proactive and personalized approach. Modern clinical protocols focus on restoring hormonal balance and supporting the body’s metabolic machinery through targeted interventions. These strategies are designed to work with the body’s physiology, helping to mitigate the effects of hormonal decline and promote long-term metabolic health.

Hormonal Optimization for Women

Hormonal optimization protocols for women in perimenopause and postmenopause are designed to restore hormonal balance in a safe and physiologic manner. This involves replacing the hormones that have declined to alleviate symptoms and provide metabolic protection.

- Testosterone Cypionate ∞ For women, low-dose testosterone therapy can be a powerful tool for metabolic health. Typically administered via weekly subcutaneous injections of 10-20 units (0.1-0.2ml), it helps to preserve and build lean muscle mass. This directly counteracts sarcopenia, thereby supporting a higher resting metabolic rate and improving insulin sensitivity. By maintaining muscle, the body has a larger “sink” for glucose, which helps to keep blood sugar levels stable.

- Progesterone ∞ Progesterone is typically prescribed for women who have a uterus to protect the uterine lining when taking estrogen. It also has systemic benefits, including promoting restful sleep and having a calming effect. Given the strong link between poor sleep, elevated cortisol, and insulin resistance, progesterone can be an important component of a comprehensive metabolic health protocol.

- Pellet Therapy ∞ This is another delivery method for hormone therapy, where small pellets containing testosterone (and sometimes estradiol) are inserted under the skin. These pellets release a steady dose of hormones over several months. Anastrozole, an aromatase inhibitor, may be included to manage the conversion of testosterone to estrogen if needed, although this is more common in male protocols.

Targeted hormone therapy, including low-dose testosterone, helps preserve the muscle mass that is crucial for maintaining a healthy metabolic rate during menopause.

The goal of these protocols is to re-establish a hormonal environment that supports metabolic efficiency, lean body mass, and overall well-being. It is a process of fine-tuning the body’s internal signals to achieve a new, healthy equilibrium.

Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy

Peptide therapies represent a more targeted approach to supporting metabolic health. These are short chains of amino acids that act as signaling molecules in the body. Certain peptides can stimulate the body’s own production of growth hormone (GH) from the pituitary gland.

Growth hormone plays a key role in metabolism, helping to build muscle, break down fat, and regulate energy. As we age, natural GH production declines. Peptide therapy can help to restore more youthful levels of GH release, which has significant metabolic benefits.

The following table outlines some of the key peptides used for metabolic health and their primary mechanisms of action:

| Peptide | Primary Mechanism of Action | Key Metabolic Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Sermorelin | A Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone (GHRH) analogue. It stimulates the pituitary gland to produce and release more of the body’s own GH. | Promotes lipolysis (fat breakdown), increases lean muscle mass, improves sleep quality, and enhances overall energy levels. |

| Ipamorelin / CJC-1295 | A combination of a GHRH analogue (CJC-1295) and a Ghrelin mimetic (Ipamorelin). This dual action provides a strong, steady pulse of GH release. | Significant fat loss, particularly visceral fat, enhanced muscle growth and recovery, improved bone density, and better sleep. |

| Tesamorelin | A potent GHRH analogue that has been specifically studied and approved for the reduction of visceral adipose tissue. | Targets and reduces abdominal fat, which is a primary driver of metabolic dysfunction in menopause. Improves lipid profiles. |

These peptide protocols are often used in conjunction with hormonal optimization to create a synergistic effect. By supporting both the sex hormones and the growth hormone axis, it is possible to address the multiple facets of menopausal metabolic decline, leading to improved body composition, energy, and long-term health.

Academic

The metabolic sequelae of menopause represent a complex interplay of endocrine signaling, cellular bioenergetics, and gene expression. To appreciate the depth of this transition, one must look beyond systemic hormonal levels and examine the molecular mechanisms at play within key metabolic tissues such as adipose, muscle, and liver.

The decline in circulating 17β-estradiol (E2) is the initiating event, but the downstream consequences are propagated through intricate signaling cascades that govern insulin action, lipid flux, and inflammatory pathways. The shift from a gynoid to an android fat distribution pattern is a gross anatomical manifestation of these subtle, yet profound, changes in cellular physiology.

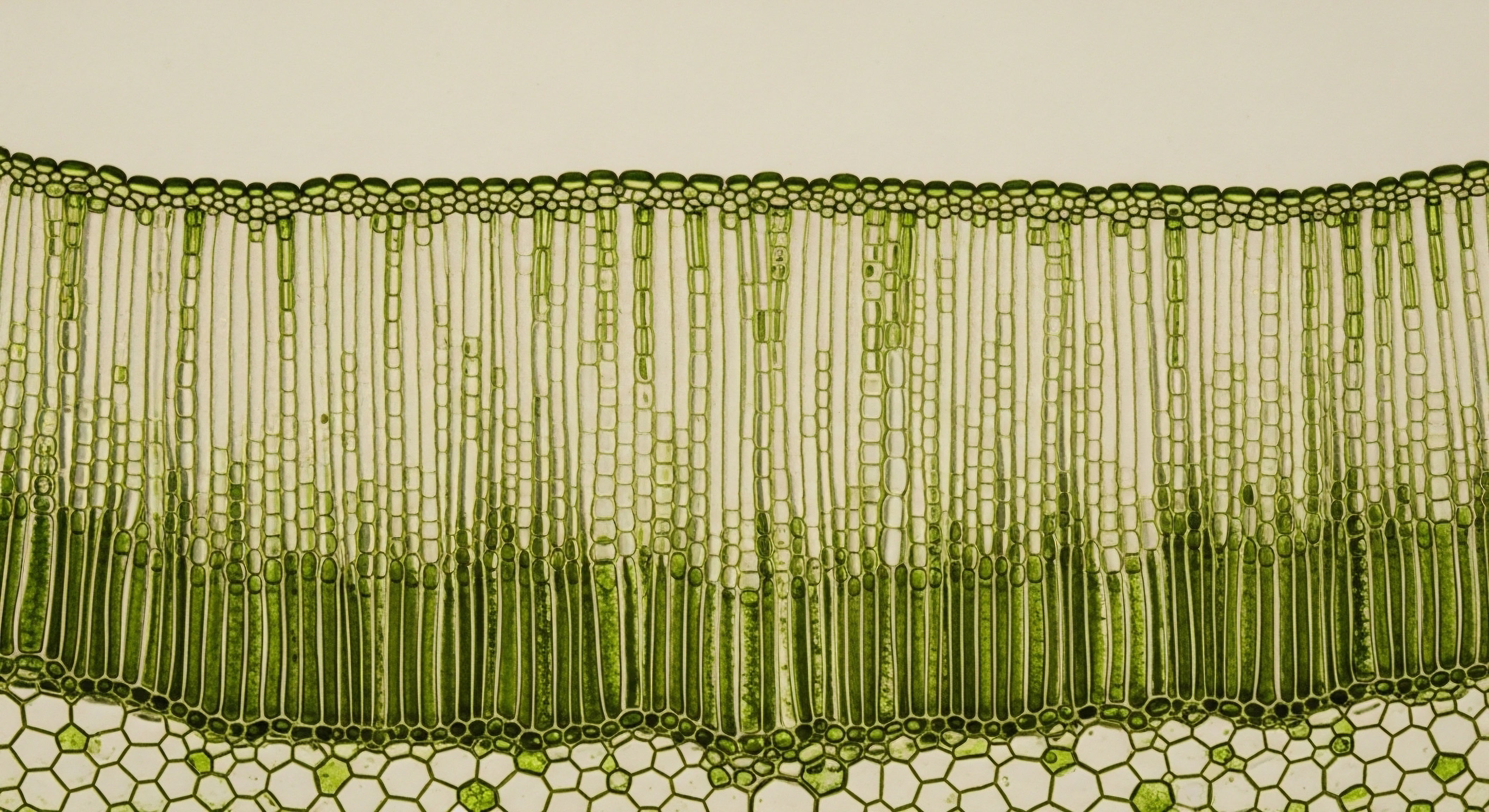

At the core of this metabolic dysregulation is the concept of tissue-specific estrogen action mediated by its receptors, Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ERα) and Estrogen Receptor Beta (ERβ). These receptors are expressed in metabolically active tissues, including pancreatic β-cells, hepatocytes, adipocytes, and skeletal myocytes.

In these cells, estrogen functions as a critical regulator of energy homeostasis. For instance, in skeletal muscle, ERα activation enhances glucose uptake by promoting the translocation of GLUT4 transporters to the cell membrane, a process that is synergistic with insulin signaling.

The loss of E2 signaling impairs this crucial step in glucose disposal, contributing directly to peripheral insulin resistance. Similarly, in the liver, estrogen helps to suppress gluconeogenesis, the production of glucose from non-carbohydrate sources. Its absence can lead to an overproduction of glucose by the liver, further elevating blood sugar levels.

Molecular Mechanisms of Menopausal Metabolic Shift

The transition to a postmenopausal state involves a fundamental reprogramming of metabolic pathways. This is not simply a passive response to the absence of a hormone, but an active adaptation that can, in some individuals, lead to a pathological state. Understanding these molecular details is essential for designing truly effective therapeutic interventions.

The Role of Adipose Tissue Inflammation

Visceral adipose tissue (VAT), which expands in the hypoestrogenic state, is a hotbed of low-grade, chronic inflammation. Adipocytes and resident immune cells (like macrophages) in VAT secrete a variety of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) and Interleukin-6 (IL-6). These cytokines can act locally and systemically to induce insulin resistance.

TNF-α, for example, can interfere with the insulin receptor signaling cascade by promoting the phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) at serine residues. This modification inhibits the normal downstream signaling through the PI3K/Akt pathway, effectively blocking insulin’s action in the cell. This creates a vicious cycle ∞ estrogen loss promotes VAT accumulation, which in turn drives inflammation and worsens insulin resistance, leading to further fat storage.

How Does Estrogen Deficiency Impact Mitochondrial Function?

Mitochondria, the powerhouses of the cell, are also targets of estrogen signaling. Estrogen promotes mitochondrial biogenesis (the creation of new mitochondria) and enhances the efficiency of the electron transport chain, the primary process of ATP production. In a hypoestrogenic environment, mitochondrial function can become impaired.

This leads to a decrease in cellular energy production and an increase in the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), or oxidative stress. This mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to insulin resistance and cellular aging. Peptide therapies, such as MOTS-c, are being explored for their ability to directly target and improve mitochondrial function, representing a novel approach to combating age-related metabolic decline.

The Intricacies of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin

Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) is a protein produced by the liver that binds to sex hormones, including testosterone and estrogen, in the bloodstream. Only the unbound, or “free,” portion of these hormones is biologically active. Oral estrogen therapies can increase the liver’s production of SHBG.

This can lead to a decrease in the amount of free testosterone available to the tissues. This is a key reason why transdermal (through the skin) delivery of estrogen is often preferred in clinical practice, as it bypasses the first-pass metabolism in the liver and has a much smaller effect on SHBG levels. This allows for the independent optimization of both estrogen and testosterone levels, which is critical for addressing the full spectrum of menopausal symptoms and metabolic changes.

Advanced Therapeutic Modalities and Their Rationale

The clinical protocols used to manage menopausal metabolic health are grounded in this deep understanding of physiology. They are designed to intervene at specific points in these biological pathways to restore a more favorable metabolic environment.

Understanding the molecular impact of estrogen on insulin signaling pathways is key to addressing the root cause of metabolic dysfunction in menopause.

The Synergistic Action of Hormonal and Peptide Therapies

A sophisticated approach to menopausal metabolic health often involves the combined use of hormonal optimization and peptide therapy. This strategy recognizes that multiple endocrine axes are affected by aging. While hormonal replacement addresses the decline in sex steroids, peptide therapies can support the Growth Hormone/IGF-1 axis.

For example, combining low-dose testosterone to preserve muscle with a peptide like Tesamorelin to specifically target visceral fat creates a powerful, multi-pronged attack on metabolic dysregulation. The testosterone helps maintain the body’s metabolic engine (muscle), while the Tesamorelin removes the primary source of metabolic inflammation (VAT). This integrated approach is a prime example of systems-biology thinking applied to clinical practice.

The following table provides a more detailed look at the evidence and rationale behind these advanced protocols.

| Therapeutic Agent | Molecular Target/Pathway | Evidence-Based Rationale and Clinical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Transdermal Estradiol | ERα and ERβ receptors in muscle, liver, adipose, and brain tissue. | Restores insulin sensitivity by enhancing GLUT4 translocation and suppressing hepatic gluconeogenesis. Improves lipid profiles. Transdermal delivery minimizes impact on SHBG, preserving free testosterone levels. |

| Micronized Progesterone | Progesterone receptors in the CNS and other tissues. | Promotes GABAergic activity in the brain, improving sleep quality. Improved sleep lowers cortisol and enhances insulin sensitivity. Essential for endometrial protection in women with a uterus taking estrogen. |

| Low-Dose Testosterone | Androgen receptors in muscle and bone. | Anabolic effects counteract sarcopenia, preserving resting metabolic rate and improving glucose disposal. A meta-analysis showed testosterone therapy improves sexual function, with some effects on lipid profiles that require monitoring. |

| CJC-1295/Ipamorelin | GHRH and Ghrelin receptors in the pituitary gland. | Stimulates endogenous pulsatile GH release, leading to increased levels of IGF-1. This promotes lipolysis and lean muscle accretion, effectively improving body composition and metabolic rate. |

| PT-141 (Bremelanotide) | Melanocortin receptors in the CNS. | While primarily used for sexual health (hypoactive sexual desire disorder), it highlights the role of central nervous system pathways in regulating aspects of health that are often affected during menopause. |

What Is the Future of Personalized Metabolic Management?

The future of managing menopausal metabolic health lies in personalization. This will involve not just measuring hormone levels, but also assessing genetic predispositions (e.g. polymorphisms in estrogen receptor genes), inflammatory markers (e.g. hs-CRP, TNF-α), and detailed metabolic testing.

For example, continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) can provide real-time feedback on an individual’s response to diet and therapies, allowing for precise adjustments. As our understanding of the molecular underpinnings of menopause deepens, we will be able to move beyond standardized protocols and toward truly individualized strategies that are tailored to each woman’s unique biology.

This approach promises to transform the management of menopause from a reactive process of symptom control to a proactive, lifelong strategy for optimal health and vitality.

References

- Davis, Susan R. et al. “Testosterone in Women ∞ a Clinical Review.” The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, vol. 3, no. 12, 2015, pp. 980-992.

- Mauvais-Jarvis, Franck, et al. “Estrogen and Androgen Receptors ∞ Regulators of Sex-Specific Intermediary Metabolism and Metabolic Diseases.” Physiological Reviews, vol. 100, no. 4, 2020, pp. 1581-1648.

- Gartoulla, P. et al. “Testosterone for peri- and postmenopausal women ∞ a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Maturitas, vol. 82, no. 3, 2015, pp. 249-258.

- Lizcano, F. and G. Guzmán. “Estrogen Deficiency and the Origin of Obesity during Menopause.” BioMed Research International, vol. 2014, 2014, Article ID 757461.

- Gupte, A. A. Pinsky, D. J. & Brinton, R. D. “Recent advances in understanding the neuroprotective actions of estrogen.” Therapeutic advances in chronic disease, vol. 1, no. 3, 2010, pp. 125 ∞ 137.

- Rettberg, J. R. Yao, J. & Brinton, R. D. “Estrogen ∞ a master regulator of bioenergetic systems in the brain and body.” Frontiers in neuroendocrinology, vol. 35, no. 1, 2014, pp. 8 ∞ 30.

- “The 2022 Hormone Therapy Position Statement of The North American Menopause Society.” Menopause, vol. 29, no. 7, 2022, pp. 767-794.

- Sigalos, J. T. & Pastuszak, A. W. “The Safety and Efficacy of Growth Hormone Secretagogues.” Sexual medicine reviews, vol. 6, no. 1, 2018, pp. 45 ∞ 53.

- Sattar, N. et al. “Cardiovascular Disease in Women ∞ a Clinical Update.” The Lancet, vol. 392, no. 10158, 2018, pp. 1016-1028.

- Sood, R. et al. “Prescribing menopausal hormone therapy ∞ an evidence-based approach.” International journal of women’s health, vol. 6, 2014, pp. 47 ∞ 57.

Reflection

Charting Your Own Biological Course

The information presented here serves as a map, detailing the intricate biological terrain of the menopausal transition. It illuminates the physiological reasons behind the changes you experience, connecting your personal feelings of shifting energy and vitality to the elegant, complex machinery of your endocrine system. This map provides the knowledge to understand the territory. It does not, however, dictate your specific path. Your journey is unique, shaped by your individual genetics, your health history, and your personal goals.

Consider this understanding as the beginning of a new, more informed conversation with your own body. The symptoms you feel are signals, messages from a system undergoing a profound recalibration. By learning the language of that system ∞ the language of hormones, metabolism, and cellular energy ∞ you gain the ability to listen more closely and respond more effectively.

The ultimate goal is to move forward with a sense of agency, equipped with the clarity to ask insightful questions and to partner with a knowledgeable clinician. This collaboration can help you chart a personalized course toward sustained wellness, transforming this period of change into a foundation for long-term strength and vitality.

Glossary

menopausal transition

adipose tissue

visceral fat

menopause

metabolic health

body composition

blood sugar levels stable

insulin sensitivity

insulin resistance

fat storage

lean muscle mass

metabolic rate

pituitary gland

visceral adipose tissue

dyslipidemia

resting metabolic rate

muscle mass

lean muscle

hormonal optimization

low-dose testosterone

blood sugar levels

hormone therapy

peptide therapies

growth hormone

peptide therapy

menopausal metabolic health