Fundamentals

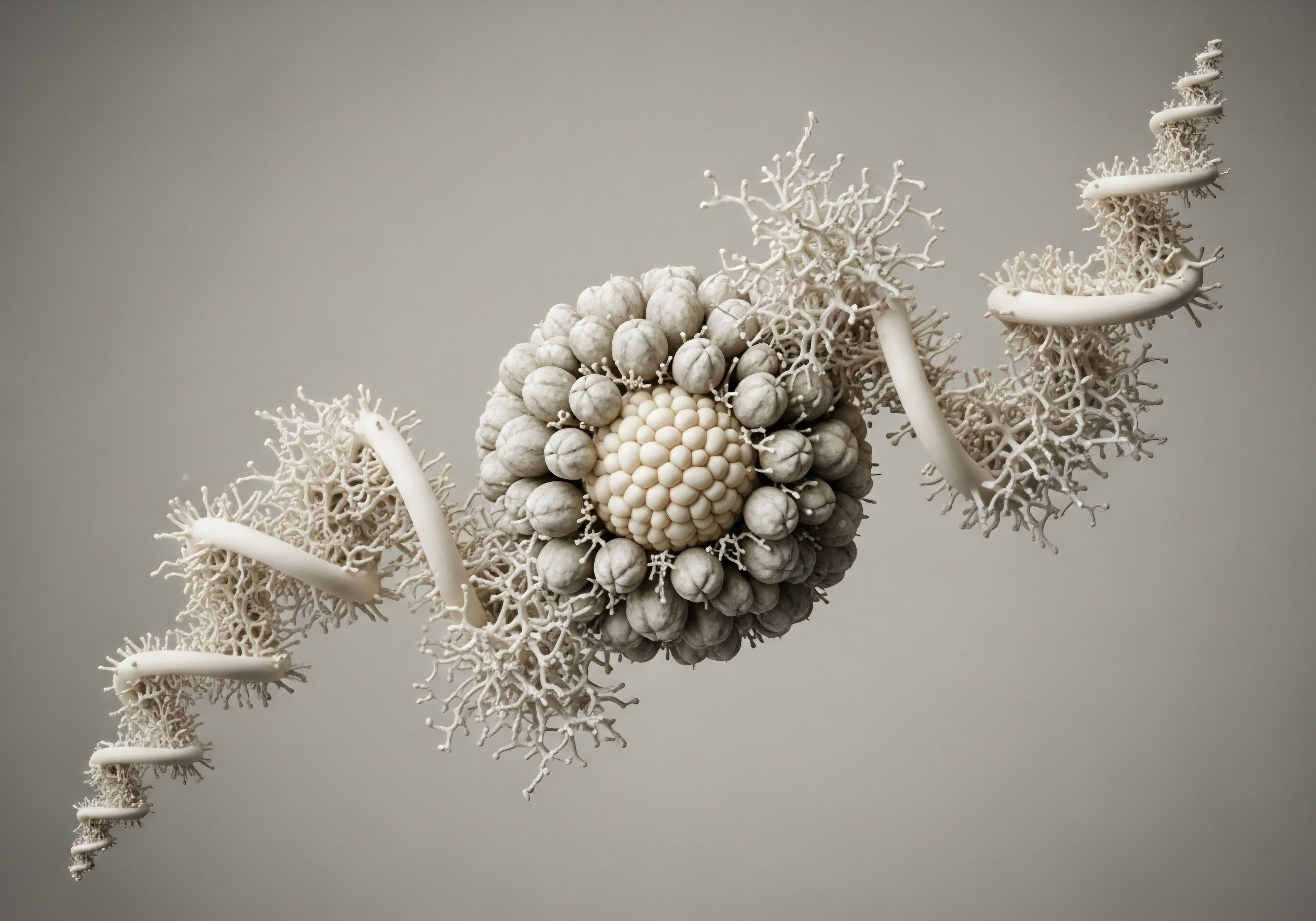

Your body is a complex, interconnected system. Every signal, from the subtle shifts in energy you feel throughout the day to the more pronounced changes that accompany different life stages, is part of a sophisticated biological dialogue.

At the center of this dialogue are your hormones, the chemical messengers that govern everything from your metabolism and mood to your reproductive health and resilience to stress. Understanding this internal ecosystem is the first step toward taking control of your health.

When you decide to engage with a workplace wellness program, you are essentially inviting a new partner into this journey. These programs can offer valuable tools, from health risk assessments to biometric screenings, designed to provide a clearer picture of your metabolic and hormonal health.

Yet, this invitation opens the door to a complex regulatory environment, one where two distinct sets of federal rules intersect ∞ those under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the interpretations set forth by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC).

At first glance, these regulations might seem like abstract legal frameworks, far removed from the personal quest for vitality. They are, however, the very rules that shape the design and implementation of the wellness programs you might consider.

They dictate how your employer can encourage you to participate, what information can be collected, and how that sensitive data about your unique biology must be protected. The core distinction between these two sets of rules lies in their primary purpose. HIPAA’s regulations, in this context, are fundamentally concerned with the structure of group health plans.

They provide a clear pathway for employers to offer financial incentives within wellness programs without violating nondiscrimination provisions. The EEOC’s rules, conversely, are rooted in civil rights law, specifically the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA). Their focus is on protecting employees from discrimination and ensuring that participation in any wellness program that involves medical inquiries is genuinely voluntary.

The essential difference is one of perspective ∞ HIPAA provides a structural safe harbor for health plan design, while the EEOC focuses on protecting individual rights and the voluntariness of participation.

This divergence in purpose leads to differing standards for incentives. Imagine a wellness program that offers a discount on your health insurance premiums for completing a biometric screening. This screening might measure your cholesterol, blood pressure, and glucose levels ∞ key indicators of your metabolic health.

HIPAA sets a clear percentage-based limit on the value of that discount, tying it to the total cost of your health insurance coverage. The EEOC, however, approaches the same scenario with a different question ∞ Is the incentive so substantial that an employee would feel compelled to participate and disclose their personal health information, even if they would otherwise prefer not to?

This question of what constitutes a “voluntary” program is where the interpretations diverge most significantly and has been the subject of considerable legal and regulatory debate. Understanding this tension is not merely an academic exercise. It directly impacts the choices available to you and the very nature of the wellness programs offered by your employer.

It shapes the boundary between encouragement and coercion, and it defines the safeguards that protect the privacy of your most personal health data, from your genetic predispositions to your current hormonal status.

The Two Pillars of Wellness Program Regulation

To truly grasp the landscape of workplace wellness programs, it is essential to understand the foundational philosophies of the two regulatory bodies that govern them. These are not overlapping sets of rules as much as they are distinct frameworks with different origins and objectives. One framework, HIPAA, was amended by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to create specific permissions for wellness incentives within health plans. The other, enforced by the EEOC, comes from a place of protecting fundamental employee rights.

HIPAA’s role is primarily to ensure that group health plans do not discriminate against individuals based on health factors. Its rules create specific “safe harbors” that allow employers to offer rewards for participation in wellness programs or for achieving certain health outcomes. These rules categorize wellness programs into two primary types:

- Participatory Programs ∞ These are programs where the reward is given simply for participating, without regard to any health outcome. Examples include attending a seminar on nutrition, completing a health risk assessment (HRA), or undergoing a biometric screening. Under HIPAA, there is no limit on the financial incentive that can be offered for participatory programs.

- Health-Contingent Programs ∞ These programs require an individual to meet a specific health-related standard to obtain a reward. They are further divided into two subcategories:

- Activity-Only Programs ∞ These involve completing a health-related activity, such as a walking program or a diet plan.

- Outcome-Based Programs ∞ These require an individual to attain or maintain a specific health outcome, such as achieving a certain BMI or cholesterol level. For these health-contingent programs, HIPAA sets a clear financial limit on the incentive, typically 30% of the total cost of health coverage, which can increase to 50% for programs designed to reduce tobacco use.

The EEOC’s authority, on the other hand, stems from laws designed to prevent discrimination in the workplace. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) prohibits discrimination based on disability and places strict limits on when an employer can make medical inquiries or require medical examinations.

The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) provides similar protections related to genetic information, which includes family medical history. When a wellness program asks questions about your health or requires a screening, it falls under the purview of the EEOC.

The central principle for the EEOC is that such programs must be “voluntary.” This concept of voluntariness is the source of the primary difference with HIPAA’s regulations. The EEOC’s concern is that a large financial incentive could effectively coerce an employee into disclosing information protected by the ADA or GINA, making the program involuntary in practice.

This has led the EEOC to propose stricter limits on incentives for any program that involves a medical exam or disability-related inquiry, viewing them through the lens of employee rights rather than health plan design.

What Defines a Voluntary Program?

The concept of “voluntariness” is the philosophical core of the distinction between HIPAA and EEOC rules, and it has profound implications for your journey toward personalized wellness through an employer-sponsored plan. While HIPAA provides a mathematical formula for incentives, the EEOC’s approach is more qualitative, centered on the employee’s experience.

A program is considered voluntary under the EEOC’s interpretation if it meets several key criteria. An employer cannot require an employee to participate in the wellness program. They also cannot deny an employee access to health coverage or take any adverse employment action if the employee chooses not to participate. The most contentious aspect of this definition, however, revolves around the size of the incentive.

The EEOC has long contended that an incentive can be so large that it renders a program involuntary. If the financial reward for participating in a biometric screening is so significant that a reasonable person would feel they cannot afford to turn it down, then the choice to participate is not truly free.

This is where the direct conflict with HIPAA’s more permissive incentive limits arises. For years, employers operated under the assumption that if they complied with HIPAA’s 30% or 50% incentive limits, they were safe. However, the EEOC challenged this assumption in court, arguing that such large incentives could be coercive under the ADA.

This led to a period of legal uncertainty, with courts weighing in and the EEOC issuing and then withdrawing proposed rules. The current state of affairs suggests that for a program to be considered voluntary by the EEOC, any incentive offered for simply participating in a program that includes a medical exam or inquiry must be minimal, or “de minimis.” This might mean a small gift card or a water bottle, a stark contrast to the thousands of dollars in premium reductions that could be permissible under HIPAA’s rules for health-contingent programs.

This distinction is critical for anyone seeking to understand their hormonal or metabolic health, as the very programs that provide this data are the ones subject to the strictest EEOC scrutiny.

Intermediate

Navigating the intricate landscape of wellness program regulations requires a deeper appreciation for the technical distinctions in how incentives are calculated and applied. For the individual engaged in a personal health journey, these details are far from academic; they directly influence the design of programs that could offer insights into metabolic function and hormonal balance.

The conflict between the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is not a simple disagreement but a fundamental variance in methodology, rooted in their different statutory missions. Understanding these mechanics illuminates why a wellness program might be structured in a particular way and what protections are in place for your sensitive health information.

The primary point of divergence is the calculation of the incentive limit. HIPAA’s rule is relatively straightforward. For health-contingent wellness programs, the total reward offered to an individual cannot exceed a specified percentage of the total cost of the health plan in which the individual is enrolled.

If an employee is enrolled in self-only coverage, the 30% limit is based on the total cost (both employer and employee contributions) of that self-only plan. If they are enrolled in family coverage, the same 30% is calculated against the much higher total cost of the family plan.

This allows for significantly larger incentives for employees with family coverage. Furthermore, HIPAA makes a clear distinction between participatory and health-contingent programs, applying no incentive limit whatsoever to programs that are purely participatory, even if they include a biometric screening or a health risk assessment.

The EEOC’s approach fundamentally alters this calculation by focusing on the principle of equal opportunity and the potential for coercion.

The EEOC’s interpretation, as outlined in its various proposed rules, establishes a different benchmark. It has consistently proposed that the 30% incentive limit for programs involving medical inquiries should be based only on the cost of self-only coverage, regardless of whether an employee has enrolled in family coverage.

The rationale behind this is to ensure that all employees are offered an incentive of similar value, preventing a situation where an employee with family coverage is offered a much larger sum of money to disclose their health information than an employee with self-only coverage.

This seemingly small change in the denominator of the equation has significant real-world consequences, often drastically reducing the maximum permissible incentive for a large portion of the workforce. This difference in calculation is a direct reflection of the agencies’ differing priorities ∞ HIPAA focuses on the cost of the specific health plan benefit, while the EEOC focuses on the potential for a financial reward to unduly influence an individual’s choice to disclose information protected by the ADA.

How Do Incentive Calculations Differ in Practice?

To fully comprehend the impact of these divergent regulatory approaches, a concrete comparison is necessary. Let us consider a hypothetical company that offers a wellness program with a biometric screening component. This screening provides valuable data points for an individual interested in their metabolic health, such as fasting glucose, lipid panels, and HbA1c levels. The company wants to offer a premium discount to encourage participation. The cost structures for their health plans are as follows:

- Total Cost of Self-Only Coverage ∞ $7,000 per year

- Total Cost of Family Coverage ∞ $20,000 per year

Now, let’s analyze how the maximum incentive would be calculated under the two different regulatory frameworks for an employee enrolled in family coverage.

Under the HIPAA framework, the calculation is based on the cost of the actual coverage tier the employee is enrolled in. Calculation ∞ 30% of $20,000 (Family Coverage Cost) = $6,000 In this scenario, the employer could offer the employee a premium discount of up to $6,000 per year for participating in the health-contingent wellness program.

Under the EEOC’s proposed framework, the calculation is based on the cost of self-only coverage, irrespective of the employee’s actual enrollment status. Calculation ∞ 30% of $7,000 (Self-Only Coverage Cost) = $2,100 Here, the maximum permissible incentive for the same employee participating in the same program would be only $2,100 per year.

The difference of $3,900 is substantial and illustrates the restrictive nature of the EEOC’s interpretation. This single change is intended to level the playing field and reduce the potential for what the agency views as economic coercion for those with more expensive family plans.

This table provides a clear, side-by-side comparison of the key differences in how these two regulatory bodies approach wellness program incentives.

| Feature | HIPAA Rules | EEOC Interpretations (based on proposed rules) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Legal Authority | Affordable Care Act (ACA) amending HIPAA’s nondiscrimination provisions. | Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA). |

| Core Objective | To provide a safe harbor for health plans to offer incentives without violating nondiscrimination rules. | To ensure employee participation in programs with medical inquiries is “voluntary” and to prevent discrimination. |

| Incentive Limit for Health-Contingent Programs | Up to 30% of the total cost of coverage (50% for tobacco cessation). | Generally limited to 30% of the cost of self-only coverage, regardless of the employee’s plan. |

| Incentive Limit for Participatory Programs (with medical inquiry) | No limit. | Must be “de minimis” (e.g. a water bottle or gift card of modest value). |

| Basis for Incentive Calculation | Based on the specific coverage tier in which the employee is enrolled (self-only, family, etc.). | Based only on the cost of the lowest-cost, self-only plan available from the employer. |

| “Gateway” Provisions | Permitted if the program is compliant with health-contingent rules. | Strictly prohibited; an employer cannot deny access to the health plan for non-participation in a wellness program with medical inquiries. |

What Is the Impact on Tobacco Cessation and Disease Management Programs?

The regulatory friction between HIPAA and the EEOC also creates complexity for specific types of wellness programs, such as those targeting tobacco use and chronic disease management. These programs are of particular interest from a metabolic health perspective, as both smoking and chronic conditions like diabetes have profound effects on the endocrine system.

HIPAA explicitly allows for a higher incentive ∞ up to 50% of the cost of coverage ∞ for tobacco cessation programs. This reflects a strong public health policy goal of reducing smoking rates. However, the EEOC’s rules introduce a critical distinction.

If the tobacco cessation program simply asks an employee whether they use tobacco, it is not considered a disability-related inquiry under the ADA, and the higher 50% incentive limit under HIPAA can apply without issue. If, however, the program requires a biometric test (like a cotinine test) to verify tobacco-free status, it becomes a medical examination subject to the ADA.

In this case, the EEOC’s more restrictive incentive limits would apply, effectively nullifying the higher 50% incentive that HIPAA otherwise permits.

This same logic extends to disease management programs. Many employers offer programs to help employees manage conditions like diabetes, which often involves regular monitoring of biomarkers like blood glucose. From a clinical perspective, these programs are highly valuable for improving metabolic health. Under HIPAA, these can be structured as health-contingent, outcome-based programs with a 30% incentive.

The EEOC, however, scrutinizes these programs closely. Because they invariably involve disability-related inquiries and medical monitoring, they must be voluntary. The EEOC has been particularly clear in prohibiting “gateway” models, where an employee is required to participate in a disease management program as a condition of being eligible for the primary health plan.

This ensures that an employee’s fundamental access to healthcare is not conditioned on their willingness to enroll in a specific wellness protocol. For the individual, this means that while your employer can strongly encourage you to participate in a program to manage your metabolic health, they cannot make it a prerequisite for receiving medical insurance.

Academic

The persistent divergence between the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act’s (HIPAA) wellness provisions and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s (EEOC) enforcement posture under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) represents a foundational conflict in U.S. health and employment policy.

This is not merely a technical dispute over incentive percentages; it is a manifestation of two competing legal philosophies. One philosophy, embodied in the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) amendments to HIPAA, prioritizes a population-based, public health objective, utilizing financial incentives as a behavioral economics tool to encourage healthier lifestyles and potentially control healthcare costs.

The other, rooted in the civil rights legacy of the ADA and GINA, prioritizes the protection of the individual from potentially discriminatory practices and coercive medical inquiries by their employer. An academic exploration of this issue must move beyond a simple comparison of rules and delve into the legal history, the statutory construction, and the long-term implications for employee health data privacy.

The genesis of this conflict can be traced to the ADA’s “voluntary” exception for employee health programs. The ADA generally forbids employers from requiring medical examinations or making inquiries about an employee’s disabilities.

However, it contains a safe harbor for “voluntary medical examinations, including voluntary medical histories, which are part of an employee health program.” The statute does not define “voluntary.” For years, this ambiguity was of little consequence.

With the passage of the ACA in 2010, which actively promoted workplace wellness programs by codifying HIPAA’s incentive structure, the definition of “voluntary” became a central point of contention. The ACA’s endorsement of incentives up to 30% (or 50% for tobacco programs) of the cost of health coverage created a direct statutory tension with the ADA’s requirement of voluntariness. The core legal question became ∞ at what point does a financial incentive, explicitly permitted by one federal statute, become coercive under another?

The legal history is defined by a cycle of regulatory action, litigation, and subsequent withdrawal, leaving employers and employees in a state of prolonged uncertainty.

This tension culminated in the EEOC’s 2016 regulations. In an attempt to harmonize the two statutes, the EEOC largely adopted HIPAA’s 30% incentive limit, applying it to both health-contingent and participatory programs that included medical inquiries. However, this attempt at reconciliation was challenged in court by the AARP ( AARP v. EEOC, 2017).

The AARP argued that an incentive of up to 30% of the total cost of coverage ∞ which could amount to several thousand dollars ∞ was so high as to be coercive, effectively forcing employees to disclose protected health information. The U.S.

District Court for the District of Columbia agreed, finding that the EEOC had failed to provide a reasoned explanation for why it believed the 30% threshold was consistent with the term “voluntary.” The court vacated the incentive limit provisions of the rules, plunging the regulatory landscape back into uncertainty.

This judicial action underscores a critical point ∞ the EEOC cannot simply defer to HIPAA’s standards. It must independently justify its rules based on the statutory language and purpose of the ADA and GINA.

The subsequent withdrawal of the 2016 rules and the issuance of new, more restrictive proposed rules in 2021 ∞ which advocated for a “de minimis” standard for many programs ∞ signals a significant retreat from the harmonization effort and a reassertion of the EEOC’s primary role as a protector of employee civil rights.

What Is the Statutory Basis for the EEOC’s Position?

The EEOC’s restrictive stance on wellness incentives is grounded in the specific language and legislative intent of the ADA and GINA. The ADA’s purpose is “to provide a clear and comprehensive national mandate for the elimination of discrimination against individuals with disabilities.” Its prohibition on non-job-related medical inquiries is a cornerstone of this protection.

The rationale is that employers should not have access to information about an employee’s health conditions, as this information could be used to make discriminatory employment decisions regarding hiring, firing, or promotion. The “voluntary” employee health program exception is a narrow carve-out.

The EEOC’s interpretation is that this exception must be construed narrowly to avoid swallowing the rule. If a large financial penalty for non-participation (or a large reward for participation) is permitted, the program ceases to be truly voluntary, and the employer effectively gains access to the very information the ADA was designed to shield.

Similarly, GINA was enacted to allay public fears that genetic information would be used by employers or insurers to discriminate against them. It prohibits employers from requesting, requiring, or purchasing genetic information of an employee or their family members. Like the ADA, GINA includes a narrow exception for voluntary wellness programs.

The EEOC applies the same logic here ∞ a significant financial incentive to disclose family medical history (which is considered genetic information) would undermine the voluntary nature of the program and violate the spirit of GINA.

The agency’s focus on a “de minimis” incentive standard for any program that is not part of a HIPAA-regulated health-contingent plan is a direct result of this statutory interpretation. It reflects a belief that the only way to ensure true voluntariness is to remove any significant financial pressure from the employee’s decision-making process.

How Does This Conflict Impact the Future of Personalized Health?

The unresolved conflict between these regulatory frameworks has profound implications for the future of personalized and preventative health, particularly as it intersects with workplace wellness. The increasing sophistication of biometric technology and genetic testing makes it possible to gain unprecedented insight into an individual’s predisposition to certain conditions and their real-time metabolic and hormonal status.

Workplace wellness programs are a logical and efficient vector for deploying these technologies at scale. However, the legal uncertainty creates a chilling effect on innovation and adoption.

Employers are caught between two competing directives. On one hand, they are encouraged by public health policy and rising healthcare costs to implement robust wellness programs that produce measurable health improvements. Such programs often require the collection of detailed health data and the use of financial incentives to drive engagement.

On the other hand, they face the risk of litigation from the EEOC if those incentives are deemed coercive. This regulatory risk may lead employers to offer only superficial wellness programs that do not involve meaningful data collection, or to abandon incentives altogether, which could dramatically reduce participation rates.

For the individual who is seeking to proactively manage their health, this could mean fewer opportunities to access valuable health information and coaching through their workplace. A program that might offer advanced hormonal panels to screen for perimenopausal changes or detailed metabolic analysis for pre-diabetes might be deemed too risky for an employer to implement due to the sensitivity of the data and the ambiguity surrounding incentive rules.

The table below outlines the legal and philosophical underpinnings of this regulatory conflict, providing a deeper analysis of the competing paradigms.

| Analytical Dimension | HIPAA/ACA Framework | EEOC (ADA/GINA) Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophical Premise | Utilitarian / Public Health. Aims to improve population health and control costs through behavioral incentives. | Deontological / Civil Rights. Aims to protect individual autonomy and prevent discrimination, regardless of the collective benefit. |

| Primary Regulated Entity | Group Health Plans. The rules are part of the regulation of insurance benefits. | Employers. The rules are part of the regulation of the employment relationship. |

| Interpretation of “Incentive” | A permissible tool for encouraging participation in health-contingent programs. | A potential instrument of coercion that could render a program “involuntary.” |

| View of Employee Health Data | A necessary input for risk assessment and the proper functioning of a health-contingent wellness program. | Highly sensitive, protected information that an employer has no right to access outside of narrow, voluntary exceptions. |

| Legal Justification for Rules | Explicit statutory authority granted by the ACA to create incentive-based wellness programs. | Interpretation of the term “voluntary” within the ADA and GINA, supported by legislative history focused on preventing employer overreach. |

| Long-Term Policy Goal | A healthier, more productive workforce and lower national healthcare expenditures. | An employment landscape free from discrimination based on disability or genetic information. |

Ultimately, resolving this conflict will likely require an act of Congress to create a single, unified standard for all workplace wellness programs. Such legislation would need to carefully balance the legitimate public health goal of promoting wellness with the equally important civil rights goal of protecting employees from discrimination and coercion.

Until then, the legal landscape will remain fragmented, and the full potential of workplace wellness programs to contribute to personalized, preventative health will be constrained by regulatory uncertainty. The ongoing dialogue between these two frameworks serves as a crucial reminder that the pursuit of health, especially when it involves the collection and use of personal biological data, is a complex endeavor with legal and ethical dimensions that are as important as the clinical ones.

References

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. “Proposed Rule on Wellness Programs.” Federal Register, vol. 86, no. 5, 11 Jan. 2021, pp. 2135-2157.

- Departments of Health and Human Services, Labor, and Treasury. “Final Rules for Grandfathered Plans, Preexisting Condition Exclusions, Lifetime and Annual Limits, Rescissions, Dependent Coverage, Appeals, and Patient Protections Under the Affordable Care Act.” Federal Register, vol. 75, no. 116, 17 June 2010, pp. 34538-34571.

- AARP v. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 267 F. Supp. 3d 14 (D.D.C. 2017).

- Schmidt, H. and Voigt, K. “The trouble with wellness incentives ∞ are they fair?” Preventive Medicine, vol. 106, 2018, pp. 213-217.

- Madison, K. M. “The tension between wellness and voluntariness.” The American Journal of Law & Medicine, vol. 42, no. 2-3, 2016, pp. 383-405.

- U.S. Department of Labor. “Fact Sheet ∞ The Affordable Care Act’s Wellness Program Rules.” 2013.

- “The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990,” Pub. L. No. 101-336, 104 Stat. 327 (1990).

- “The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008,” Pub. L. No. 110-233, 122 Stat. 881 (2008).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Workplace Wellness Programs ∞ A Guide for Employers.” 2017.

- Horwitz, J. R. “HIPAA and the new world of health care.” Health Affairs, vol. 24, no. 6, 2005, pp. 1493-1502.

Reflection

You began this exploration seeking to understand a set of rules, but what you have uncovered is a conversation about values. The journey into the regulatory world of wellness programs reveals a deep societal dialogue about the balance between collective well-being and individual autonomy.

The knowledge you have gained about HIPAA and the EEOC is more than just a map of legal boundaries; it is a lens through which to view your own health journey in a broader context. Your personal biology, your unique hormonal signature, and your metabolic function are yours alone. Yet, when you engage with systems designed to support your health, you become part of this larger conversation.

Where Does Your Personal Health Journey Intersect with These Broader Systems?

Consider the data points that chart your path to vitality ∞ the lab results, the biometric markers, the subtle feedback from your own body. These are the elements of your personal health narrative. As you move forward, think about how you want to share that narrative and with whom.

The regulations discussed here are the gatekeepers of that sharing in the workplace context. They shape the questions that can be asked, the incentives that can be offered, and the protections that must be afforded to your most private information. Understanding their structure gives you the power to engage with these programs on your own terms, with full awareness of the framework in which they operate.

What Does True Partnership in Health Look like for You?

Ultimately, the path to sustained health is a collaborative one, built on trust and informed choice. Whether your partners are clinicians, coaches, or the wellness programs offered to you, the foundation of that partnership is your own understanding.

The complexities of the endocrine system and the nuances of metabolic health are mirrored by the complexities of the systems we build to manage them. By embracing this knowledge, you are not just learning the rules; you are preparing yourself to be an active, empowered participant in the lifelong project of stewarding your own well-being. The journey forward is one of continued learning, personal discovery, and the confident application of that knowledge to build a life of vitality.