Fundamentals

Your body’s internal chemistry tells a story. Every fluctuation in energy, mood, and physical experience is a chapter in the intricate narrative of your endocrine system. When you use a wellness application to track your sleep, nutrition, or menstrual cycle, you are recording the footnotes to this story.

This data, which feels deeply personal, is a direct reflection of your hormonal and metabolic function. Understanding who has access to this story and how it is protected is central to reclaiming your vitality. The conversation about data privacy, specifically the divergence between the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), is a conversation about the sanctity of your biological information.

These two regulatory frameworks govern the disclosure of health data, yet they operate from different philosophical starting points, particularly for non-clinical wellness applications that fall outside traditional healthcare settings. HIPAA was designed to protect patient information within the clinical ecosystem of healthcare providers, insurance companies, and their direct business associates.

Its protections are specific to the healthcare industry. GDPR, conversely, is a sweeping data privacy law that protects the personal data of all EU residents, regardless of the industry collecting it. It sees your wellness data not just as a medical record, but as a fundamental piece of your personal identity that requires robust protection everywhere.

The core distinction arises from scope ∞ HIPAA protects designated health information within the US healthcare system, while GDPR protects all personal data for EU residents across all sectors.

This distinction has profound implications for the data you generate daily. Information logged into a fertility tracker or a metabolic health monitor, while intimately tied to your endocrine health, may not be covered by HIPAA if the application has no formal relationship with a healthcare provider.

Under GDPR, this same information is explicitly defined as “data concerning health” and is granted a higher level of protection known as “special category data,” requiring your explicit consent for any processing. The divergence is not merely technical; it reflects two different views on the nature of personal wellness data and where the boundary of privacy should be drawn.

Intermediate

To appreciate the functional differences between HIPAA and GDPR for your wellness data, we must examine the mechanics of consent and data rights. Your endocrine system operates on a principle of feedback loops; a hormonal signal is sent, a response is generated, and that response informs the next signal.

Similarly, these legal frameworks are built on feedback loops of consent and control, but the sensitivity of their triggers varies significantly. GDPR is constructed around the principle of explicit and informed consent for each specific processing activity. This means a wellness app must clearly state what data it is collecting and for what purpose, and you must actively agree to each purpose. The power to grant or withhold consent rests firmly with you.

What Is the Practical Difference in Consent Models?

HIPAA’s consent model is more contextual. While it requires authorization for uses outside of core healthcare functions like marketing, it permits the use and disclosure of your Protected Health Information (PHI) without explicit consent for treatment, payment, and healthcare operations. The challenge for non-clinical wellness apps is that they often exist in a gray area.

If an app is not a “covered entity” or a “business associate” under HIPAA, its data handling practices are not governed by HIPAA’s rules at all. GDPR makes no such distinction; if an app processes the data of an EU resident, it is subject to GDPR’s stringent consent requirements, period.

GDPR grants individuals a suite of enforceable rights, including data access, correction, and erasure, that are more extensive than those provided by HIPAA.

This divergence extends to the rights you have over your data. GDPR provides a set of clearly defined individual rights that are transformative for personal data ownership. These are often referred to as foundational data subject rights.

- The Right to Access ∞ You can request a copy of all personal data a company holds on you.

- The Right to Rectification ∞ You have the right to correct inaccurate personal data.

- The Right to Erasure (The Right to be Forgotten) ∞ You can request the deletion of your personal data under certain circumstances.

- The Right to Data Portability ∞ This allows you to obtain your data in a structured, machine-readable format to move it from one controller to another.

HIPAA provides a right to access and amend your health records held by covered entities, but it does not contain a universal “right to be forgotten” or the same broad portability rights. The implications for your wellness journey are direct. Under GDPR, you have the explicit right to demand that a wellness company delete the years of menstrual cycle or blood glucose data you have logged, a powerful tool for managing your digital footprint.

Comparing Key Disclosure Requirements

The structural differences in how each regulation treats health data are best understood through a direct comparison.

| Feature | HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) | GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) |

|---|---|---|

| Protected Data | Protected Health Information (PHI) held by covered entities and business associates. | All personal data, with “data concerning health” treated as a special category requiring extra protection. |

| Scope | Applies to US healthcare providers, health plans, and their business associates. | Applies to any organization processing the personal data of individuals residing in the EU, regardless of the organization’s location. |

| Consent for Disclosure | Authorization is required for uses outside of treatment, payment, and healthcare operations. | Explicit, unambiguous, and specific consent is required for each data processing activity. |

| Right to Erasure | Does not include a “right to be forgotten.” Data is retained based on medical record laws. | Includes a “right to be forgotten,” allowing individuals to request data deletion. |

| Breach Notification | Affected individuals must be notified within 60 days; the Department of Health and Human Services must be notified if over 500 individuals are affected. | The relevant data protection authority must be notified within 72 hours of breach discovery. |

Academic

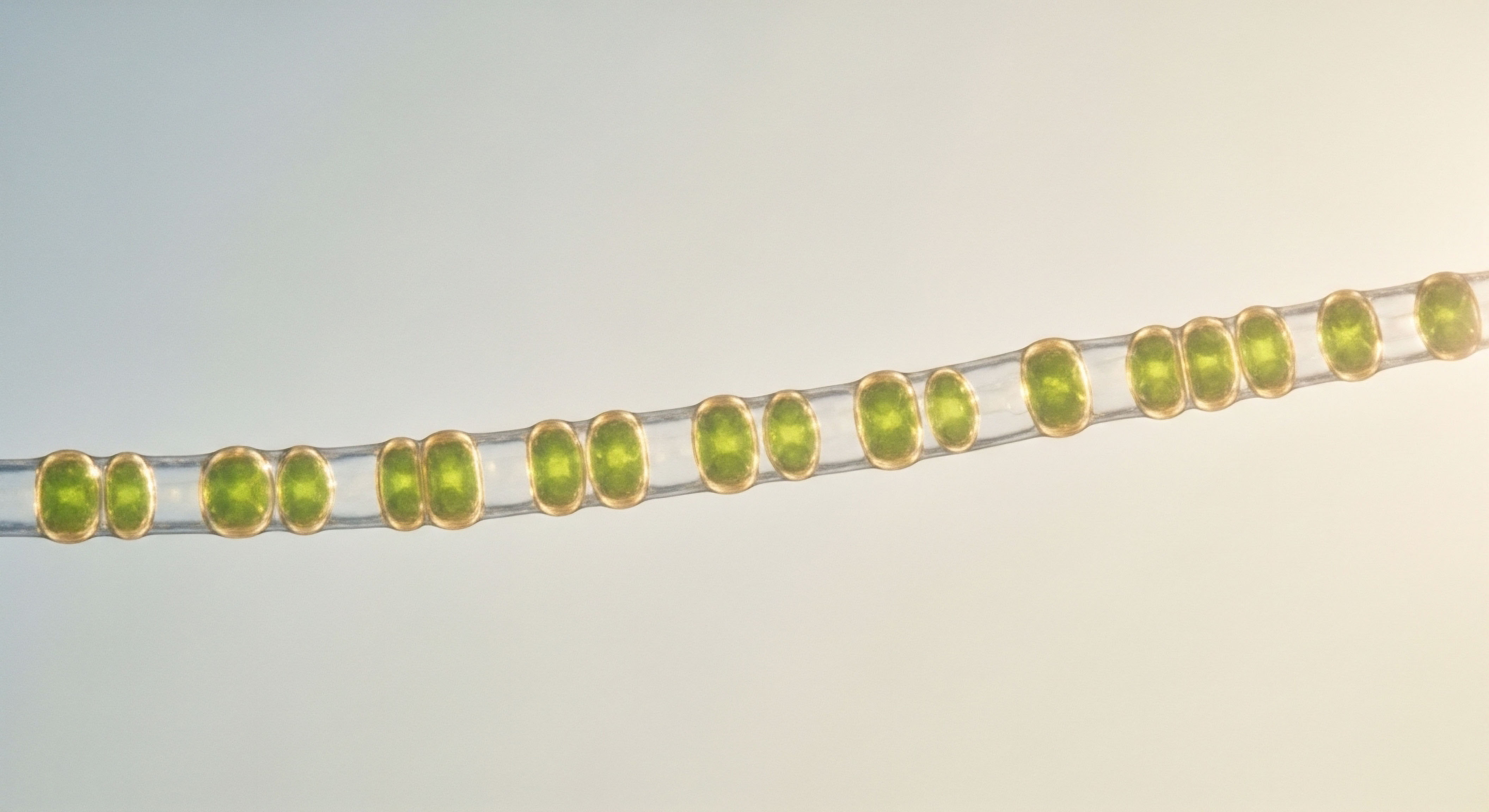

The divergence between HIPAA and GDPR reaches its most critical point in the complex realities of data anonymization. From a systems-biology perspective, the data collected by wellness applications is a high-fidelity proxy for the activity of your neuroendocrine system. This is not static information.

It is a dynamic, longitudinal dataset reflecting the pulsatile release of hormones, the circadian rhythm of cortisol, and the cyclical nature of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. The very richness that makes this data valuable for personal wellness also makes it profoundly difficult to truly anonymize.

Why Is Hormonal Data so Hard to Anonymize?

Both HIPAA and GDPR have provisions for data to be used for research or other purposes once it has been de-identified (HIPAA) or anonymized (GDPR). HIPAA provides specific “safe harbor” methods for de-identification, such as the removal of 18 specific identifiers. GDPR, however, holds a much higher standard. For data to be considered truly anonymous under GDPR, the risk of re-identification must be effectively zero. This is a formidable threshold when dealing with physiological data.

Consider the data generated by tracking the menstrual cycle. This data stream includes cycle length, body temperature fluctuations, and user-logged symptoms. This pattern is a direct output of the complex interplay between Luteinizing Hormone (LH), Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH), estrogen, and progesterone. Each individual’s cycle has a unique signature, a specific cadence and variability.

When this uniquely identifying time-series data is combined with other seemingly innocuous data points like location or device ID, the potential for re-identification becomes substantial. A dataset stripped of name and email can still point to a single individual when their unique biological rhythm is visible.

The unique, time-series nature of endocrine data challenges the very concept of anonymization, particularly under the stringent standards set by GDPR.

This has significant implications for how non-clinical wellness companies can use aggregated data. A company operating under GDPR’s framework must be far more cautious when using customer data for research or product development, as the bar for successful anonymization is exceptionally high.

HIPAA’s de-identification standard, while robust, was not designed for the era of machine learning and high-dimensional biometric data, where algorithms can find patterns and re-identify individuals from datasets that would meet the safe harbor criteria.

Data Sovereignty and Biological Identity

The core philosophical divergence can be framed as a question of data sovereignty. GDPR operates from a rights-based framework, establishing data protection as a fundamental human right. It endows individuals with a form of sovereignty over their personal information, including their biological data. Your health data is an extension of you, and you have the ultimate say in how it is used and the right to retract it.

HIPAA approaches the issue from a security and industry-regulation perspective. Its goal is to ensure that regulated entities within the healthcare system secure patient data properly and use it for permissible purposes. This is a critical function, but it was not designed to govern the vast ecosystem of wellness technologies that now capture data of equal or greater sensitivity.

The result is a regulatory gap in the United States, where the intimate details of your metabolic and endocrine function, logged into a non-clinical app, may receive fewer protections than a billing record at a hospital. This divergence underscores a central question for the future of personalized wellness ∞ who is the ultimate steward of your most personal biological story?

| Anonymization Aspect | HIPAA De-Identification | GDPR Anonymization |

|---|---|---|

| Standard | Removal of 18 specified identifiers (Safe Harbor) or expert determination of low re-identification risk. | Data must be rendered in such a way that the data subject is not or is no longer identifiable. High threshold. |

| Re-identification Risk | Focuses on removing direct identifiers. Risk of re-identification with modern data science techniques remains. | Requires that the risk of re-identification by any means reasonably likely to be used is effectively eliminated. |

| Application to Wellness Data | May allow for broader use of “de-identified” datasets that could still contain unique physiological patterns. | Severely restricts the use of datasets for secondary purposes unless true, robust anonymization can be proven. |

| Philosophical Basis | A procedural approach to removing specific personal data points. | A principles-based approach focused on irrevocably breaking the link to an individual. |

References

- Cohen, I. Glenn, and Michelle M. Mello. “HIPAA and the Evolving Health Data Landscape.” JAMA, vol. 320, no. 3, 2018, pp. 239-240.

- Price, W. Nicholson, and I. Glenn Cohen. “Privacy in the Age of Medical Big Data.” Nature Medicine, vol. 25, no. 1, 2019, pp. 37-43.

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. “Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation).” Official Journal of the European Union, L 119/1, 2016.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. “Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule.” HHS.gov, 2013.

- Vayena, Effy, et al. “The International Landscape of Health Data Regulation.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 378, no. 12, 2018, pp. 1152-1160.

- Mantelero, Alessandro. “The GDPR and the Digital Transformation of Healthcare.” European Journal of Health Law, vol. 25, no. 5, 2018, pp. 495-515.

- Finck, Michèle. “De-Identification, Anonymisation and Pseudonymisation.” The Cambridge Handbook of Consumer Privacy, edited by Evan Selinger et al. Cambridge University Press, 2018, pp. 238-254.

Reflection

The information you gather about your body is the raw material for profound self-knowledge and biological optimization. Each data point is a clue to the underlying systems that govern your vitality. Understanding the legal frameworks that protect this data is the first step toward becoming an active, informed steward of your own health narrative.

As you continue on your path, consider the digital extensions of your biological self. Ask how your story is being stored, who has access to the chapters, and what it means to truly own the narrative of your own well-being. This awareness is the foundation upon which a truly personalized and empowered health journey is built.