Fundamentals

The experience of diminished vitality, a subtle yet persistent shift in how your body feels and functions, often prompts a deeper inquiry into one’s biological systems. Perhaps you have noticed a decline in physical drive, a reduction in muscle tone, or a general sense of fatigue that simply was not present before.

These sensations are not merely isolated occurrences; they frequently signal changes within the intricate network of the body’s endocrine system, particularly concerning hormonal balance. Understanding these internal shifts is the initial step toward reclaiming a sense of robust health and functional capacity.

For many individuals, especially men, these symptoms can point toward a reduction in natural testosterone levels, a condition known as hypogonadism. When considering options to address such a decline, Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) frequently arises as a powerful intervention.

TRT involves introducing exogenous testosterone into the body to restore circulating levels to a healthy range, thereby alleviating a spectrum of symptoms from low energy to reduced libido. While TRT offers substantial benefits for overall well-being, it also introduces a significant consideration for those who value their reproductive potential ∞ the impact on testicular function and fertility.

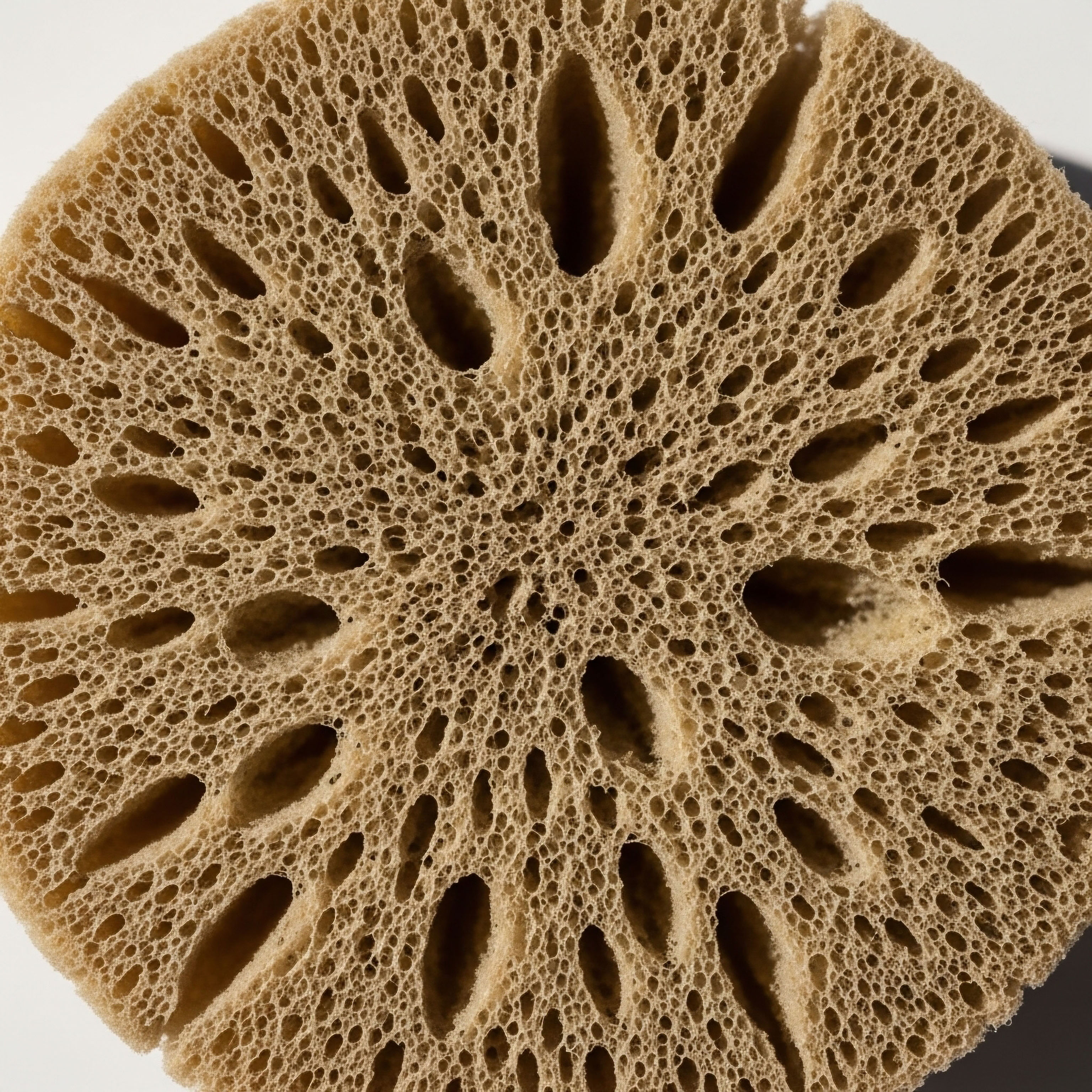

The body operates through sophisticated feedback mechanisms, much like a finely tuned internal thermostat. When external testosterone is introduced, the brain’s signaling centers, specifically the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, detect these elevated levels. This detection triggers a natural response to reduce the body’s own production of hormones that stimulate the testes.

This intricate communication pathway is known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. The hypothalamus releases Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH), which prompts the pituitary to secrete Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). LH then stimulates the Leydig cells in the testes to produce testosterone, while FSH supports the Sertoli cells in producing sperm.

When exogenous testosterone is administered, this delicate HPG axis experiences suppression. The brain perceives sufficient testosterone and consequently reduces its output of GnRH, leading to a decrease in LH and FSH from the pituitary. With less LH and FSH signaling, the testes receive fewer instructions to produce their own testosterone and sperm.

This physiological response can result in two primary outcomes ∞ a reduction in testicular size, often referred to as testicular atrophy, and a significant impairment of sperm production, potentially leading to infertility.

Testosterone replacement therapy, while beneficial for vitality, can suppress the body’s natural hormonal signals, affecting testicular size and sperm production.

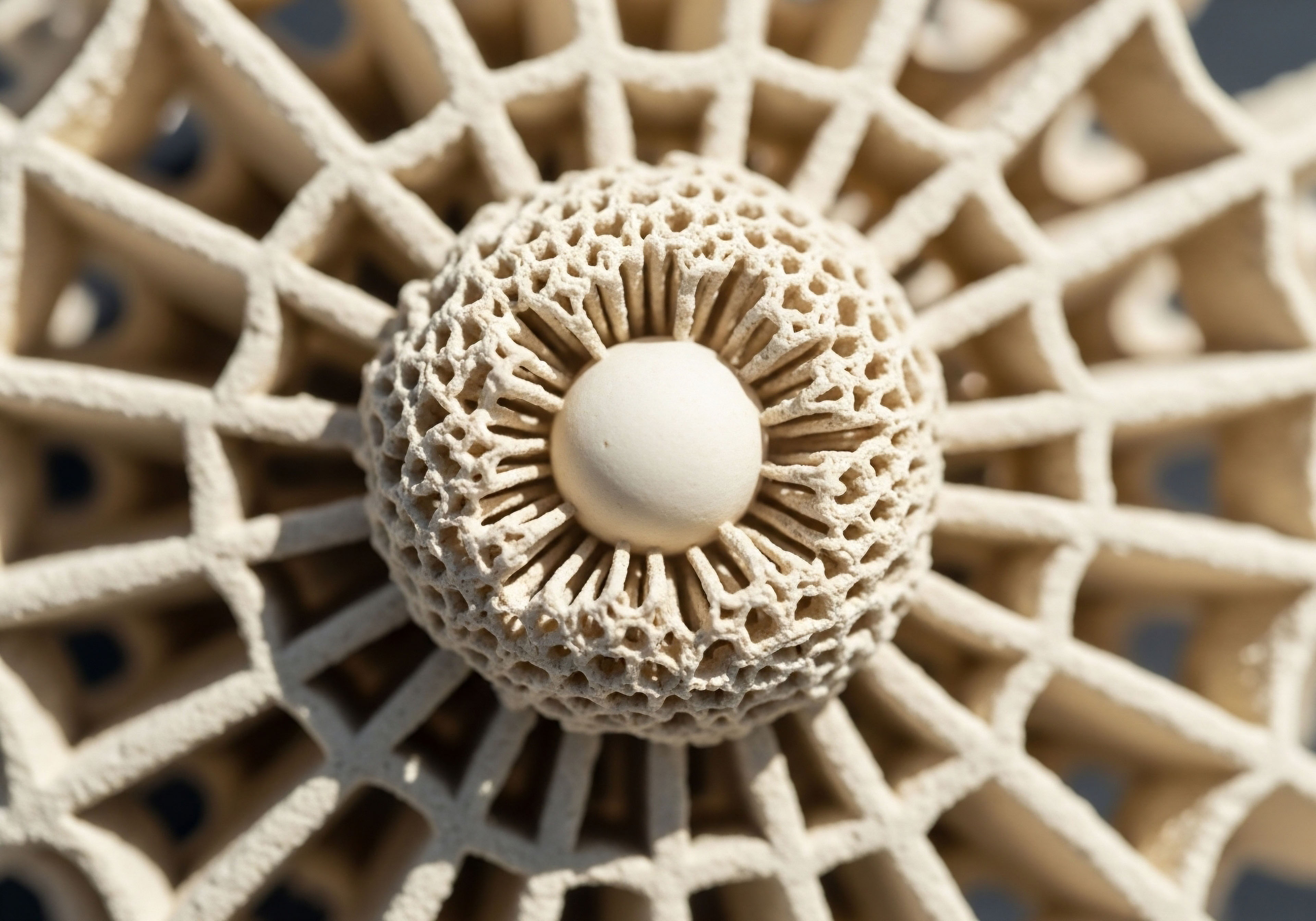

For individuals who are considering TRT but wish to preserve their testicular function or maintain fertility, this presents a genuine concern. Fortunately, medical science offers strategies to mitigate these effects. Two primary classes of compounds are often employed as adjunct therapies alongside TRT ∞ Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (HCG) and GnRH analogs, such as Gonadorelin.

These agents work through distinct yet related mechanisms to sustain testicular activity despite the presence of exogenous testosterone. Understanding how each of these compounds interacts with the HPG axis is vital for making informed decisions about personalized wellness protocols.

Intermediate

Navigating the complexities of hormonal optimization protocols requires a clear understanding of how various agents interact with the body’s internal communication systems. When considering testosterone replacement therapy, the goal extends beyond simply elevating circulating testosterone levels; it includes preserving the integrity and function of the entire endocrine network.

The suppression of the HPG axis by exogenous testosterone, leading to testicular atrophy and impaired spermatogenesis, is a well-documented physiological consequence. To counteract this, specific therapeutic agents are integrated into treatment plans.

How Does HCG Support Testicular Function during TRT?

Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (HCG) stands as a widely utilized adjunct therapy in male hormone optimization protocols. Its mechanism of action centers on its structural similarity to Luteinizing Hormone (LH). In the natural HPG axis, LH is the primary signal from the pituitary gland that prompts the Leydig cells within the testes to produce testosterone. When TRT suppresses endogenous LH production, HCG steps in as a substitute signal.

By binding to the same LH receptors on the Leydig cells, HCG directly stimulates the testes to continue their production of intratesticular testosterone. This localized testosterone is absolutely essential for the process of spermatogenesis, the creation of sperm. Without sufficient intratesticular testosterone, sperm production diminishes significantly, even if systemic testosterone levels are optimized by TRT. The sustained stimulation provided by HCG helps to maintain testicular volume and prevent the shrinkage that often accompanies TRT monotherapy.

Typical HCG protocols involve subcutaneous injections, often administered two to three times per week, alongside the regular testosterone injections. Dosing can vary, but common ranges include 250 to 500 International Units (IU) per injection. Clinical studies have demonstrated that even relatively low doses of HCG can effectively maintain intratesticular testosterone levels, significantly mitigating the suppressive effects of exogenous testosterone on sperm production and testicular size.

HCG acts as an LH mimic, directly stimulating testicular testosterone production to preserve size and sperm function during TRT.

While HCG is highly effective, it is important to monitor potential side effects. Because HCG stimulates Leydig cells to produce testosterone, and testosterone can be converted into estrogen via the aromatase enzyme, some individuals may experience elevated estrogen levels. This can lead to symptoms such as fluid retention or gynecomastia. Consequently, regular blood work to assess estrogen levels is a standard component of HCG protocols, and an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole may be prescribed if estrogen levels become too high.

What Role Do GnRH Analogs Play in Testicular Preservation?

GnRH analogs, such as Gonadorelin, represent a different strategy for testicular preservation during TRT. Unlike HCG, which bypasses the pituitary and acts directly on the testes, GnRH analogs work higher up the HPG axis, at the level of the hypothalamus and pituitary. Gonadorelin is a synthetic version of the naturally occurring Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH).

In a healthy system, GnRH is released in a pulsatile fashion from the hypothalamus, signaling the pituitary gland to release LH and FSH. When exogenous testosterone suppresses this natural pulsatile release, administering Gonadorelin in a pulsatile manner can effectively “trick” the pituitary into continuing its production and release of LH and FSH. This stimulation, in turn, maintains the downstream signaling to the testes, preserving their ability to produce both testosterone and sperm.

This approach is considered more “physiologic” because it aims to keep the entire HPG axis engaged, rather than bypassing a component of it. Gonadorelin is typically administered via subcutaneous injections, often multiple times per week or even daily, to mimic the natural pulsatile release of GnRH. While it is a newer option compared to HCG for this specific application, preliminary data and clinical experience suggest it can effectively sustain endogenous LH/FSH production and support testicular function.

One potential advantage of GnRH analogs over HCG is a potentially lower risk of estrogen elevation, as the stimulation of LH and FSH is more regulated by the body’s own feedback mechanisms, rather than a direct, supraphysiologic stimulation of Leydig cells. However, more extensive long-term studies are still emerging to fully delineate the comparative benefits and considerations of GnRH analogs in this context.

The decision between HCG and GnRH analogs often depends on individual patient factors, treatment goals, and physician preference. Both agents offer viable pathways to support testicular health and fertility while receiving the benefits of testosterone optimization.

- HCG Mechanism ∞ Mimics LH, directly stimulating Leydig cells in the testes.

- GnRH Analog Mechanism ∞ Stimulates the pituitary to release LH and FSH, maintaining the upstream HPG axis.

- Testicular Atrophy Prevention ∞ Both agents aim to prevent the reduction in testicular size caused by TRT.

- Fertility Preservation ∞ Both support spermatogenesis by maintaining intratesticular testosterone levels.

- Administration ∞ Both are typically administered via subcutaneous injections.

| Feature | Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (HCG) | GnRH Analogs (e.g. Gonadorelin) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Action Site | Directly on Leydig cells in testes | On pituitary gland (via hypothalamus) |

| Mimics Which Hormone? | Luteinizing Hormone (LH) | Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) |

| Impact on HPG Axis | Bypasses pituitary, direct testicular stimulation | Maintains pulsatile LH/FSH release from pituitary |

| Estrogen Conversion Risk | Potentially higher due to direct Leydig cell stimulation | Potentially lower, more physiologic regulation |

| Established Use | Well-established, long clinical history | Newer approach, emerging clinical data |

| Administration Frequency | Typically 2-3 times per week | Often multiple times per week or daily |

Academic

The sophisticated interplay of biochemical signals within the endocrine system represents a frontier of personalized wellness. When considering the long-term implications of exogenous testosterone administration, a deep understanding of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis becomes paramount.

The exogenous introduction of testosterone, while effective in ameliorating symptoms of hypogonadism, initiates a cascade of negative feedback that fundamentally alters the endogenous hormonal milieu. This suppression of the HPG axis leads to a reduction in gonadotropin secretion, specifically LH and FSH, which are indispensable for both Leydig cell steroidogenesis and Sertoli cell-mediated spermatogenesis.

How Do These Agents Modulate the Endocrine System?

The mechanisms by which HCG and GnRH analogs counteract this suppression, thereby preserving testicular function, reveal distinct yet complementary strategies. Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (HCG), a glycoprotein hormone, shares significant structural homology with LH, allowing it to bind to the same Luteinizing Hormone/Choriogonadotropin Receptor (LHCGR) on Leydig cells.

This direct agonistic action on the testicular Leydig cells stimulates the synthesis and secretion of intratesticular testosterone, which is critical for maintaining the local androgenic environment necessary for germ cell development. Studies have shown that even low-dose HCG, administered concomitantly with testosterone enanthate, can maintain intratesticular testosterone levels within the normal physiological range in healthy men undergoing gonadotropin suppression. This sustained intratesticular androgen concentration is a primary driver for preserving spermatogenesis and mitigating testicular atrophy.

Conversely, GnRH analogs, such as Gonadorelin, operate at a higher echelon of the HPG axis. Gonadorelin is a decapeptide identical to the endogenous Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) produced by the hypothalamus. Its therapeutic utility in this context hinges on its ability to stimulate the gonadotrophs in the anterior pituitary gland.

When administered in a pulsatile fashion, mimicking the natural hypothalamic release, Gonadorelin prompts the pituitary to secrete endogenous LH and FSH. This sustained pulsatile stimulation of the pituitary maintains the integrity of the entire neuroendocrine cascade, ensuring that the testes continue to receive the necessary trophic signals for both testosterone production and spermatogenesis.

HCG directly stimulates testicular cells, while GnRH analogs reactivate the brain’s signals to the testes, both aiming to preserve function.

The distinction in their points of action carries implications for their physiological effects and potential side effect profiles. HCG’s direct and potent stimulation of Leydig cells can lead to a more pronounced increase in intratesticular testosterone, which, while beneficial for fertility, may also result in higher systemic testosterone levels and, consequently, increased aromatization to estrogen. This necessitates careful monitoring of estradiol levels and, in some cases, the co-administration of an aromatase inhibitor to manage potential estrogenic side effects.

In contrast, GnRH analogs, by restoring the natural pulsatile release of LH and FSH, may offer a more physiologically regulated approach. The pituitary’s response to GnRH is subject to its own feedback mechanisms, potentially leading to a more controlled and less supraphysiologic stimulation of gonadal function.

This could theoretically translate to a lower incidence of estrogen-related side effects compared to HCG, although comprehensive comparative trials are still needed to fully substantiate this hypothesis in the context of TRT adjunct therapy.

What Are the Clinical and Research Implications?

The clinical application of these agents is primarily driven by the patient’s desire for fertility preservation or the prevention of testicular atrophy. For men actively seeking to conceive, the evidence supporting HCG’s role in maintaining spermatogenesis during TRT is robust. Studies have shown that combining HCG with testosterone therapy can prevent azoospermia (absence of sperm) and maintain sperm parameters.

The effectiveness of HCG in preserving intratesticular testosterone levels, even in the face of exogenous testosterone-induced gonadotropin suppression, underscores its clinical utility.

The role of GnRH analogs in this specific application, while promising, is still evolving. While GnRH agonists have been extensively studied in other reproductive contexts, such as assisted reproductive technologies, their specific application for testicular preservation during TRT is a more recent area of clinical exploration. The concept of maintaining the endogenous HPG axis through pulsatile GnRH administration is physiologically sound, offering a pathway to support natural testicular function.

Considerations for clinical decision-making extend beyond the primary mechanism of action. Patient adherence, cost, and individual response to therapy are all factors. HCG is generally more accessible and has a longer history of use in this context, making it a common first-line choice. GnRH analogs, while potentially offering a more “natural” stimulation, may require more frequent injections and could be less widely available or covered by insurance.

Choosing between HCG and GnRH analogs involves weighing their distinct mechanisms, potential side effects, and individual patient needs.

Future research will likely continue to refine our understanding of these agents, potentially identifying specific patient populations who may benefit more from one approach over the other. The long-term effects on testicular health, genetic integrity of sperm, and overall endocrine resilience remain areas of ongoing investigation. The goal remains to provide comprehensive hormonal optimization that not only alleviates symptoms but also preserves the intricate biological systems that underpin overall well-being.

- HCG Efficacy ∞ Proven to maintain intratesticular testosterone and sperm production during TRT.

- GnRH Analog Efficacy ∞ Emerging evidence suggests effectiveness in sustaining endogenous LH/FSH and testicular function.

- Estrogen Management ∞ HCG may necessitate more frequent monitoring and potential co-administration of aromatase inhibitors.

- Physiological Approach ∞ GnRH analogs offer a more upstream, physiologically aligned method of HPG axis maintenance.

- Clinical Choice ∞ Selection depends on patient goals, fertility desires, side effect profiles, and physician experience.

| Parameter | HCG (Human Chorionic Gonadotropin) | GnRH Analogs (e.g. Gonadorelin) |

|---|---|---|

| Receptor Target | Luteinizing Hormone/Choriogonadotropin Receptor (LHCGR) on Leydig cells | GnRH receptors on pituitary gonadotrophs |

| Direct vs. Indirect Action | Directly stimulates testicular steroidogenesis | Indirectly stimulates testicular function via pituitary LH/FSH release |

| Impact on Spermatogenesis | Maintains intratesticular testosterone, supporting Sertoli cells and germ cell development | Maintains FSH signaling to Sertoli cells and LH signaling to Leydig cells, supporting both aspects of spermatogenesis |

| Established Research Base | Extensive clinical data for fertility preservation in TRT users | Growing body of research, particularly for pulsatile administration in hypogonadism |

| Cost and Accessibility | Generally more widely available and often covered by insurance for this indication | May be less common, potentially higher cost, and less insurance coverage for this specific use |

| Monitoring Considerations | Requires monitoring of estradiol due to potential for increased aromatization | Requires monitoring of LH, FSH, and testosterone to ensure HPG axis engagement |

References

- Coviello, A. D. Matsumoto, A. M. Bremner, W. J. et al. Low-dose human chorionic gonadotropin maintains intratesticular testosterone in normal men with testosterone-induced gonadotropin suppression. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2005; 90(5) ∞ 2595-2602.

- Hsieh, T. C. Pastuszak, A. W. Hwang, K. et al. Concomitant intramuscular human chorionic gonadotropin preserves spermatogenesis in men undergoing testosterone replacement therapy. Journal of Urology, 2013; 189(2) ∞ 647-650.

- Johnson, D. H. et al. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist treatment for protection of spermatogenesis during chemotherapy. Cancer, 1985; 55(10) ∞ 2418-2422.

- Matthiesson, K. L. et al. Suppression of intratesticular testosterone by a GnRH antagonist in men. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2005; 90(7) ∞ 4218-4224.

- Meirow, D. et al. GnRH agonist treatment for fertility preservation in women undergoing chemotherapy. Human Reproduction Update, 2004; 10(6) ∞ 513-521.

- Redman, J. R. & Bajorunas, D. R. Testicular function after chemotherapy for Hodgkin’s disease. Annals of Internal Medicine, 1987; 107(6) ∞ 874-878.

- Shetty, G. et al. GnRH agonist treatment enhances recovery of spermatogenesis after cytotoxic damage in rats. Biology of Reproduction, 2002; 66(5) ∞ 1400-1406.

- Waxman, J. et al. The effect of chemotherapy on testicular function in patients with Hodgkin’s disease. Cancer, 1987; 59(9) ∞ 1590-1594.

- Zhengwei, Y. et al. GnRH antagonist-induced suppression of intratesticular testosterone in macaques. Journal of Andrology, 1998; 19(4) ∞ 456-462.

Reflection

The journey toward optimal health is deeply personal, marked by a continuous process of understanding and recalibration. As you consider the intricate mechanisms of hormonal health and the specific considerations surrounding testosterone optimization, remember that knowledge itself is a powerful tool. The insights gained into how GnRH analogs and HCG interact with your biological systems are not merely academic facts; they are guideposts for making choices that align with your individual goals for vitality and well-term well-being.

This exploration of endocrine recalibration underscores a fundamental truth ∞ your body possesses an inherent intelligence, and supporting its natural pathways can yield profound benefits. Whether your focus is on maintaining reproductive potential, preserving physical attributes, or simply ensuring the most harmonious hormonal environment, the available protocols offer avenues for personalized care. The path forward involves thoughtful dialogue with a knowledgeable practitioner, someone who can translate complex clinical science into actionable strategies tailored precisely for you.

Embrace this opportunity to become a more informed participant in your own health narrative. The ability to engage with these concepts, to ask discerning questions, and to seek out protocols that honor your body’s innate design represents a significant step toward reclaiming full function without compromise. Your well-being is a dynamic landscape, and with the right understanding and guidance, you can navigate it with confidence and clarity.