Fundamentals

The experience of carrying excess weight is often framed as a personal failure, a deficit of willpower. You may feel a profound sense of frustration, as if your body is working against your most determined efforts. This internal battle is a common narrative, yet it overlooks the sophisticated biological systems that govern our weight.

Your body operates on a complex network of hormonal signals, a constant conversation between your gut, your fat cells, and your brain. This is where the story of modern weight management begins, with an understanding of your own physiology.

At the center of this regulation is a concept known as the metabolic set point. Think of it as a thermostat for your body fat. Your brain, specifically a region called the hypothalamus, has a weight range it considers normal and works diligently to maintain.

When you lose weight through caloric restriction, the body perceives this as a threat. In response, it deploys powerful countermeasures. It increases the production of hunger hormones like ghrelin, making you feel ravenous. Simultaneously, it decreases metabolic rate, meaning you burn fewer calories at rest.

This is a survival mechanism, honed over millennia, and it is the primary reason why traditional dieting so often results in weight regain. The feeling of fighting an uphill battle is real; you are contending with a deeply ingrained biological drive.

Understanding that weight regulation is a physiological process, not a moral one, is the first step toward finding a sustainable solution.

The Hormonal Orchestra of Energy Balance

Your body’s management of energy is conducted by an orchestra of hormones. Each plays a specific role in signaling hunger, satiety, and energy storage. Key players in this system include:

- Leptin This hormone is produced by fat cells and acts as a long-term satiety signal. In theory, more body fat means more leptin, which should tell the brain to decrease appetite and increase energy expenditure. In obesity, a state of “leptin resistance” can develop, where the brain becomes deaf to these signals.

- Ghrelin Often called the “hunger hormone,” ghrelin is produced in the stomach. Its levels rise before meals to stimulate appetite and fall after eating. In many individuals with obesity, the post-meal drop in ghrelin is less pronounced, leading to a quicker return of hunger.

- Insulin Released by the pancreas in response to rising blood sugar, insulin’s primary job is to help cells absorb glucose for energy. It also promotes fat storage and inhibits the breakdown of fat. Insulin resistance, a hallmark of metabolic syndrome, disrupts this entire process.

It is within this intricate hormonal dialogue that new interventions find their purpose. They are designed to work with your body’s signaling pathways, recalibrating the conversation rather than simply overriding it with force.

Introducing GLP-1 Receptor Agonists

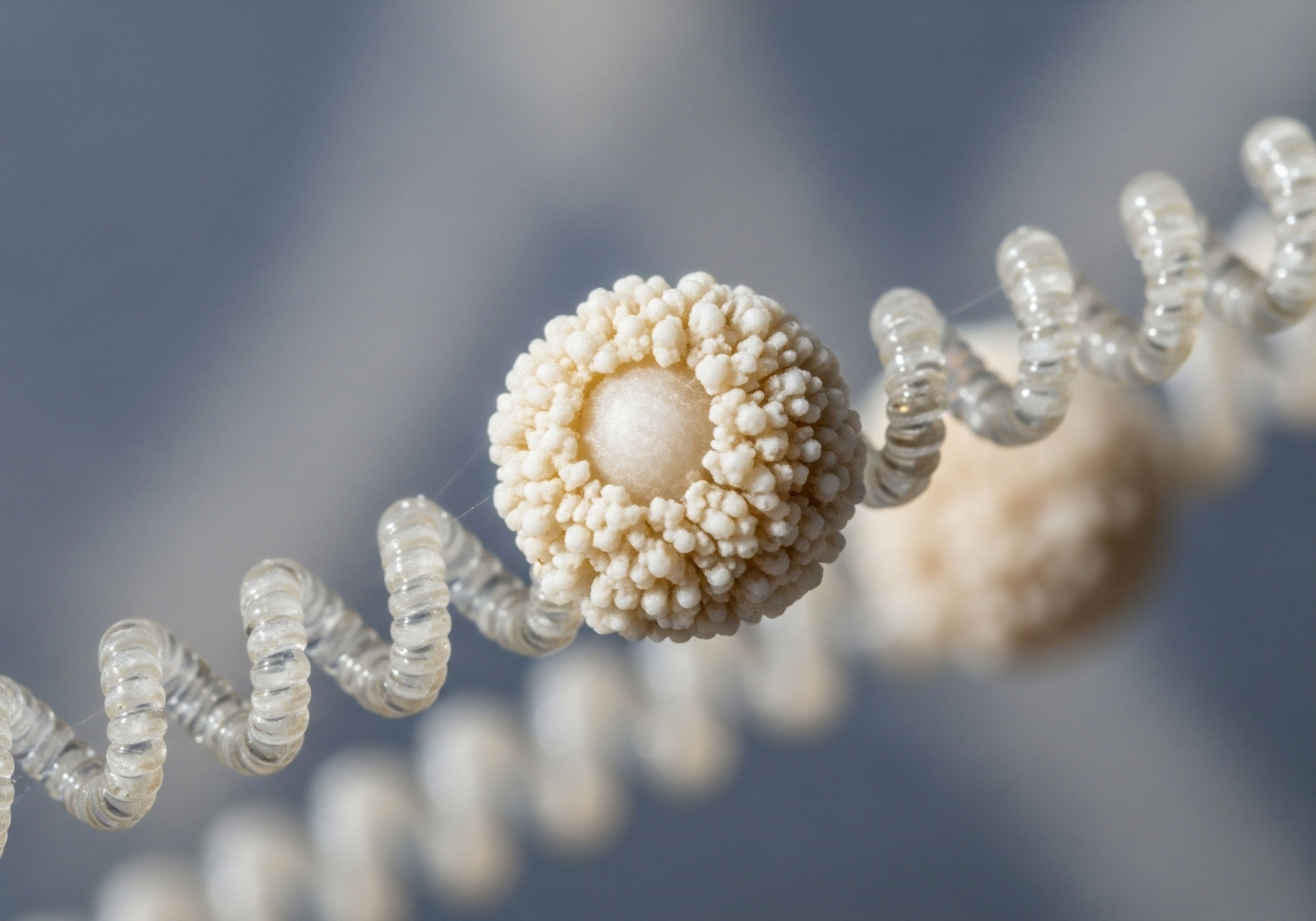

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is a natural hormone produced in your gut in response to food. It is a key messenger in the gut-brain axis, the communication superhighway that tells your brain you have eaten and are satisfied. GLP-1 medications are synthetic versions of this hormone.

They work by activating the same receptors as your natural GLP-1, but they are designed to last much longer, providing a sustained and powerful signal. Their action is multifaceted, addressing several aspects of the body’s energy regulation system. They slow down gastric emptying, which means food stays in your stomach longer, contributing to a prolonged feeling of fullness.

They also act directly on the appetite centers in the brain, reducing hunger signals and food cravings. This approach helps to lower the body’s perceived set point, allowing for weight loss without triggering the intense hormonal backlash associated with traditional dieting.

A Spectrum of Interventions

GLP-1 medications represent one powerful tool, but they exist on a spectrum of weight management strategies. Each approach has a different mechanism, level of efficacy, and role in a personalized health protocol.

- Lifestyle and Behavioral Modification This is the foundation of any health plan. It involves optimizing nutrition, engaging in regular physical activity, and developing behavioral strategies for long-term adherence. While essential, for many with chronic obesity, lifestyle changes alone are often insufficient to overcome the body’s powerful compensatory mechanisms. A modest weight loss of 5-10% is a successful outcome with this approach and yields significant health benefits.

- Older Pharmacotherapy Medications like phentermine have been used for decades. Phentermine acts as a stimulant to suppress appetite. Its use is typically limited to the short term due to its mechanism and side effect profile. Orlistat works differently, by blocking the absorption of dietary fat in the gut.

- Bariatric Surgery Procedures like sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass represent the most effective and durable intervention for severe obesity. These surgeries physically alter the digestive system, but their primary power comes from the profound hormonal changes they induce, including a significant increase in the body’s own GLP-1 production. This makes surgery a metabolic intervention as much as a physical one.

Choosing the right intervention requires a deep understanding of your individual biology, your health history, and your goals. The journey begins with acknowledging the complex science at play and moving away from a model of blame toward one of biological understanding and empowerment.

Intermediate

Moving beyond foundational concepts, a clinical comparison of weight management interventions requires a detailed look at their mechanisms, expected outcomes, and the specific patient profiles for which they are best suited. The decision between a GLP-1 agonist, a different class of medication, or a surgical procedure is a clinical one, grounded in data from large-scale trials and guided by an individual’s complete metabolic and hormonal profile.

How Do GLP-1 Agonists Compare Mechanistically?

GLP-1 receptor agonists (RAs) have a unique mechanism that sets them apart from older anti-obesity medications. Their function is to mimic and amplify the body’s natural post-meal satiety signals. This integrated physiological approach leads to a different clinical experience and outcome profile compared to other pharmacological options.

GLP-1 RAs Vs. Stimulant Appetite Suppressants

The most common older class of weight management medication includes sympathomimetic amines like phentermine. The comparison reveals two fundamentally different strategies for influencing energy balance.

| Feature | GLP-1 Receptor Agonists (e.g. Semaglutide) | Stimulant Appetite Suppressants (e.g. Phentermine) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Mimics the endogenous hormone GLP-1, activating receptors in the brain, pancreas, and gut. This reduces appetite, slows gastric emptying, and improves glucose control. | Increases the release of norepinephrine in the brain, which suppresses appetite through a central nervous system stimulant effect. |

| Therapeutic Approach | Metabolic regulation. It works within the body’s existing hormonal feedback loops to promote satiety and regulate insulin. | Neurochemical stimulation. It directly acts on brain chemistry to reduce hunger signals. |

| Duration of Use | Approved for long-term, chronic weight management. | Typically approved for short-term use (up to 12 weeks) due to potential for tolerance and cardiovascular side effects. |

| Metabolic Benefits | Significant improvements in glycemic control, blood pressure, and lipid profiles, independent of weight loss. | Metabolic benefits are primarily a secondary effect of weight loss itself. |

| Common Side Effects | Gastrointestinal issues are most common, including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, especially during dose escalation. | Increased heart rate, elevated blood pressure, insomnia, anxiety, and dry mouth. |

The clinical data underscores these differences. Trials for semaglutide (STEP trials) and tirzepatide (a dual GLP-1/GIP agonist; SURMOUNT trials) show average weight loss ranging from 15% to over 22% of total body weight. Phentermine’s efficacy is more modest and its short-term indication makes it a tool for initiating weight loss, not for sustained management.

The Endocrine Society clinical practice guidelines recommend pharmacotherapy as an adjunct to lifestyle modifications for individuals with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m², or a BMI ≥ 27 kg/m² with at least one weight-related comorbidity.

The choice between these medication classes depends on the therapeutic goal ∞ initiating a short-term weight loss effort versus implementing a long-term metabolic regulation strategy.

Pharmacotherapy versus Surgical Intervention

Bariatric surgery has long been the gold standard for profound and durable weight loss. With the advent of highly effective GLP-1 agonists, the comparison between these two powerful interventions has become a central topic in metabolic medicine. While both are effective, they differ significantly in the magnitude of weight loss, durability of results, and risk profile.

Recent systematic reviews and head-to-head studies provide a clear picture of their comparative efficacy. Bariatric procedures like Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and sleeve gastrectomy (SG) consistently produce greater weight loss than pharmacotherapy. One year after surgery, patients can expect an average total body weight loss of 29-32% for SG and RYGB, respectively. This effect is remarkably durable, with weight loss of approximately 25% maintained for up to ten years post-surgery.

In contrast, GLP-1 medications, while highly effective, show a different trajectory. Weight loss with tirzepatide can reach 22.5% and with semaglutide up to 15%, but these results plateau around 17-18 months of continuous treatment. A critical distinction is the effect of discontinuation. Upon stopping GLP-1 therapy, patients typically regain a significant portion, around 50%, of the lost weight within a year.

Surgical outcomes, by contrast, are sustained without ongoing intervention. This highlights a fundamental difference ∞ surgery physically and hormonally alters the system for the long term, while medication manages the system for as long as it is administered.

What Is the Role of Hormonal Optimization in Weight Management?

A comprehensive approach to weight management must also consider the patient’s broader endocrine health. Hormonal imbalances, particularly in sex hormones, can be both a cause and a consequence of obesity and metabolic dysfunction, creating a vicious cycle. Addressing these underlying issues is often a key component of a successful, personalized protocol.

In men, there is a well-established bidirectional relationship between low testosterone and obesity. Adipose tissue, particularly visceral fat, contains the enzyme aromatase, which converts testosterone into estradiol. Increased fat mass leads to higher aromatase activity, lowering testosterone levels. In turn, low testosterone promotes the storage of fat and reduces muscle mass, further exacerbating obesity.

This creates a self-perpetuating cycle. For men with diagnosed hypogonadism and metabolic syndrome, Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) can be a critical intervention. By restoring testosterone to optimal levels, TRT can improve insulin sensitivity, increase lean body mass, and reduce visceral adiposity, making it a powerful adjunct to other weight management strategies.

In women, the hormonal shifts of perimenopause and menopause contribute significantly to changes in body composition. The decline in estrogen is associated with a shift in fat storage from the hips and thighs to the abdominal area, increasing visceral fat and the risk of metabolic syndrome.

The concurrent decline in testosterone can contribute to loss of muscle mass and lower metabolic rate. Judicious use of hormone replacement therapy, potentially including low-dose testosterone, can help mitigate these changes, supporting metabolic health and facilitating weight management during this life stage.

Therefore, a truly personalized wellness protocol integrates weight management interventions like GLP-1s or surgery with a thorough assessment and optimization of the entire endocrine system. This systems-based approach addresses the interconnected nature of metabolic and hormonal health.

Academic

An academic exploration of weight management interventions moves into the realm of systems biology, examining the intricate interplay between neurohormonal signaling pathways, cellular metabolism, and long-term clinical outcomes. The comparison of GLP-1 receptor agonists to other strategies is analyzed not just by percentage of weight loss, but by their differential effects on the complex machinery of human metabolic regulation, including the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis and the gut-brain axis.

Deep Dive into Neurohormonal Mechanisms

The efficacy of GLP-1 RAs is rooted in their ability to modulate the gut-brain axis, a bidirectional communication network that is fundamental to energy homeostasis. When endogenous GLP-1 is released from L-cells in the intestine after a meal, it acts on local vagal afferent nerves and also enters circulation to act directly on key nuclei within the brainstem and hypothalamus.

Specifically, GLP-1 RAs influence neurons in the area postrema and nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) in the brainstem, which then project to hypothalamic areas responsible for appetite regulation, such as the arcuate nucleus (ARC).

Within the ARC, these medications potentiate the activity of pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons, which promote satiety, and inhibit Agouti-related peptide (AgRP) and Neuropeptide Y (NPY) neurons, which drive hunger. This neurochemical modulation is the primary driver of the profound appetite suppression seen with these agents.

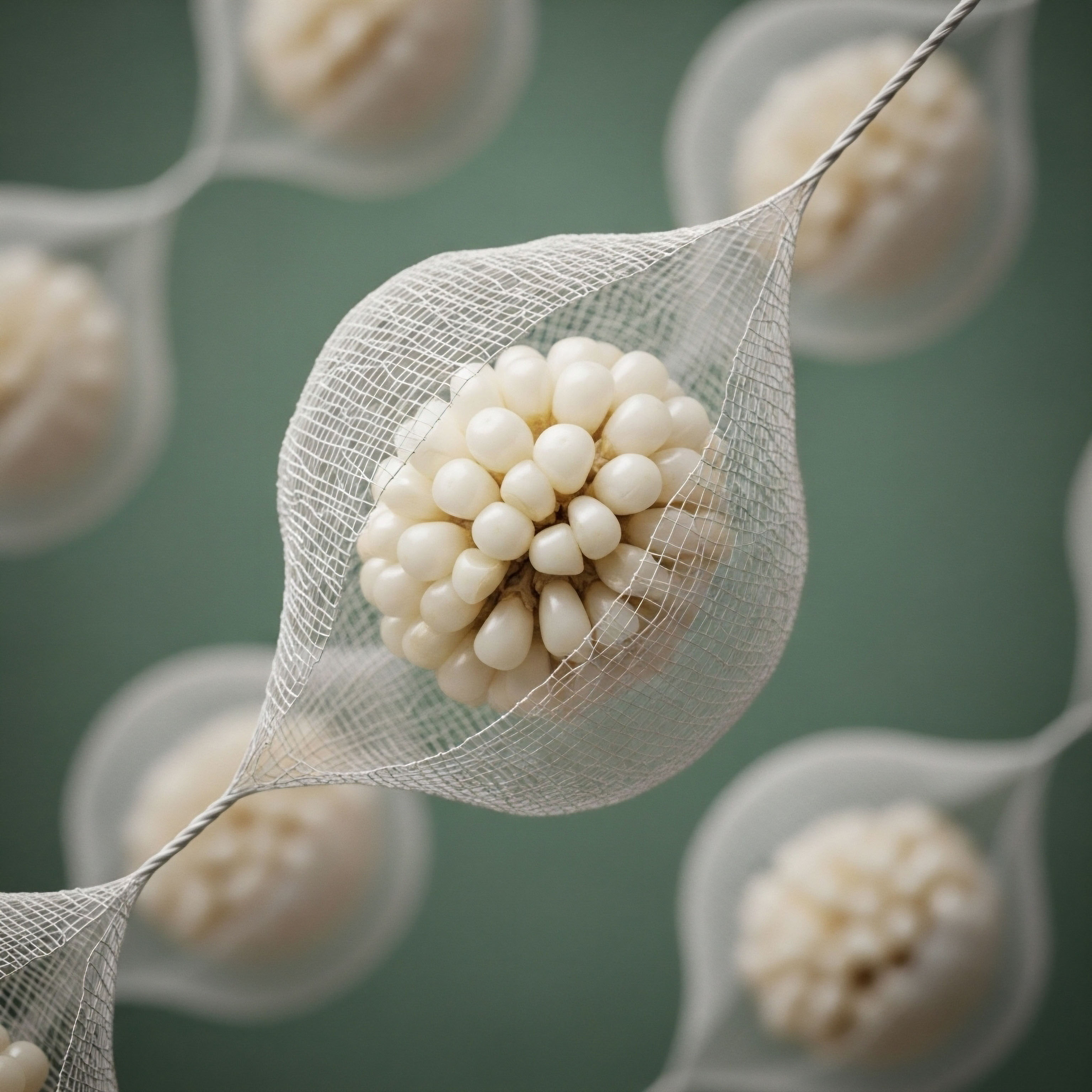

Bariatric surgery achieves its superior and more durable effects by inducing a more profound and permanent alteration of this same axis. Procedures like RYGB result in an exaggerated and sustained postprandial release of endogenous GLP-1 and other gut hormones like Peptide YY (PYY).

This is due to the rapid transit of nutrients to the distal small intestine, leading to a supraphysiological stimulation of L-cells. The result is a durable recalibration of the gut-brain signaling that mirrors, and in fact exceeds, the pharmacological effect of exogenous GLP-1 RAs. This explains why surgery is often referred to as a “metabolic” procedure; its primary mechanism is hormonal, not simply restrictive or malabsorptive.

Why Does Weight Regain Occur after Stopping GLP-1 Therapy?

The phenomenon of weight regain following the cessation of GLP-1 RA therapy is a direct consequence of their pharmacological nature. These medications do not permanently alter the underlying physiology of weight regulation. They act as a continuous external signal that manages the system.

When the medication is withdrawn, the body’s homeostatic mechanisms, which were being pharmacologically overridden, re-assert themselves. The brain’s metabolic set point, which was effectively lowered by the drug, reverts to its original, higher level. The powerful compensatory responses to weight loss ∞ increased ghrelin, decreased leptin sensitivity, and reduced metabolic rate ∞ are unmasked.

This is a critical distinction from bariatric surgery, where the anatomical changes create a new, lasting physiological state with chronically altered gut hormone secretion. The current clinical paradigm for GLP-1 RAs is one of chronic disease management, analogous to statins for hypercholesterolemia or antihypertensives for high blood pressure, requiring continuous therapy to maintain the benefit.

The durability of an intervention is directly related to its ability to induce permanent physiological change versus providing temporary pharmacological management.

The Intersection of Metabolic and Gonadal Endocrinology

A sophisticated understanding of weight management must integrate the influence of the HPG axis. The link between hypogonadism and metabolic syndrome is not merely correlational; it is mechanistically intertwined. Testosterone exerts direct effects on key metabolic tissues. In adipose tissue, androgens inhibit lipoprotein lipase (LPL), an enzyme that promotes fat storage, and stimulate lipolysis.

They also influence adipocyte differentiation, favoring the development of smaller, more insulin-sensitive fat cells. In muscle, testosterone has an anabolic effect, promoting protein synthesis and increasing lean body mass, which is a primary determinant of resting metabolic rate.

The “Hypogonadal-Obesity-Adipocytokine Hypothesis” provides a framework for this vicious cycle. Obesity increases the expression of aromatase in fat tissue, which converts testosterone to estradiol, suppressing the HPG axis. The resulting low testosterone further promotes adipogenesis, creating a feedback loop. This cycle is also fueled by adipocytokines like leptin and inflammatory cytokines (e.g. TNF-α, IL-6) released from hypertrophied adipocytes, which further inhibit hypothalamic GnRH and pituitary LH secretion.

From a therapeutic standpoint, this suggests a multi-pronged approach. For a hypogonadal male with obesity, treatment with a GLP-1 RA can effectively reduce adiposity. This reduction in fat mass can decrease aromatase activity and inflammation, potentially improving endogenous testosterone production.

Concurrently, initiating TRT can directly address the low testosterone, enhancing lean mass, improving insulin sensitivity, and further promoting fat loss. This combined protocol targets both sides of the cycle, potentially leading to a more robust and holistic improvement in metabolic health than either intervention alone.

| Intervention | Primary Target Axis | Mechanism of Action | Durability | Associated Hormonal Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLP-1 RAs | Gut-Brain Axis | Pharmacological activation of GLP-1 receptors, reducing appetite and improving glucose homeostasis. | Low (Requires continuous use). | May indirectly improve HPG axis function by reducing adiposity and inflammation. |

| Bariatric Surgery | Gut-Brain Axis | Anatomical alteration leading to supraphysiological, chronic release of endogenous GLP-1 and PYY. | High (Sustained long-term). | Often leads to significant improvement or resolution of hypogonadism and other comorbidities. |

| Testosterone Therapy | HPG Axis | Exogenous replacement of testosterone to restore physiological levels. | Medium (Requires continuous use). | Directly improves lean mass, reduces fat mass, and enhances insulin sensitivity. |

| Lifestyle Modification | General Metabolism | Creates a caloric deficit and improves insulin sensitivity through diet and exercise. | Very Low (High rate of regain). | Modest weight loss can lead to improvements in both metabolic and gonadal hormone profiles. |

What Are the Future Directions in Metabolic Intervention?

The field is evolving toward more nuanced and combination therapies. The success of tirzepatide, a dual GLP-1/GIP agonist, demonstrates the potential of targeting multiple hormonal pathways simultaneously for an additive or synergistic effect. Future research is exploring triple-agonist therapies (GLP-1, GIP, and glucagon) and combining GLP-1 RAs with other molecules that target different aspects of metabolism, such as amylin analogues.

Furthermore, the integration of pharmacotherapy with hormonal optimization protocols, such as TRT or peptide therapies (e.g. Sermorelin, Ipamorelin) aimed at preserving lean mass, represents a more complete, systems-based approach to not just weight loss, but the comprehensive restoration of metabolic health and optimal body composition.

References

- Apovian, Caroline M. et al. “Pharmacological management of obesity ∞ an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 100.2 (2015) ∞ 342-362.

- Byrne, James P. “Bariatric surgery more effective than GLP-1 agonist weight loss drugs, study finds.” The Pharmaceutical Journal (2024).

- Saad, Farid, et al. “The role of testosterone in the metabolic syndrome ∞ a review.” The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology 114.1-2 (2009) ∞ 40-43.

- Kelly, Daniel M. and T. Hugh Jones. “Testosterone ∞ a metabolic hormone in health and disease.” Journal of Endocrinology 217.3 (2013) ∞ R25-R45.

- American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. “Head-to-head Study Shows Bariatric Surgery Superior to GLP-1 Drugs for Weight Loss.” Press Release (2025).

- Jones, T. Hugh. “Testosterone, obesity, diabetes and the metabolic syndrome.” Testosterone. Cambridge University Press, 2009. 157-172.

- Kapoor, D. et al. “Testosterone and the metabolic syndrome.” Therapeutic Advances in Endocrinology and Metabolism 2.4 (2011) ∞ 137-145.

- Activ8 Health. “Semaglutide vs. Phentermine ∞ Which Is Better for Weight Loss.” (2025).

- Wadden, Thomas A. et al. “Weight regain after stopping semaglutide treatment for obesity.” New England Journal of Medicine 386.14 (2022) ∞ 1369-1371.

- Samakar, Kamran and Vidmar, Alaina. “When Should Kids Get Bariatric Surgery? Obesity Medicine Experts Share the Science.” Children’s Hospital Los Angeles (2025).

Reflection

Charting Your Own Biological Path

You have now journeyed through the complex science of metabolic regulation, from the hormonal signals that govern hunger to the clinical data comparing powerful therapeutic tools. This knowledge is the starting point. It transforms the conversation from one of frustration and self-blame to one of strategic, informed action. Your body is not a simple machine; it is a dynamic, interconnected system with its own history and its own unique biological tendencies.

Consider the information presented here as a map. It shows the different routes available ∞ the steady path of pharmacological management, the profound and durable change offered by metabolic surgery, the foundational support of hormonal optimization. The map provides the terrain, but it cannot choose your destination. That is the work of a personalized health journey, one undertaken with a clinical guide who can help you interpret your own biological signals, from lab results to your lived experience.

The ultimate goal extends beyond a number on a scale. It is about restoring function, vitality, and the feeling of being at home in your own body. It is about recalibrating the system so that it works with you. As you move forward, the most important step is to ask how this new understanding applies to your unique physiology and to seek a partnership that can help you translate this knowledge into your own story of reclaimed health.

Glossary

weight management

metabolic set point

metabolic rate

weight regain

metabolic syndrome

gut-brain axis

weight loss

phentermine

sleeve gastrectomy

bariatric surgery

weight management interventions

glp-1 receptor agonists

semaglutide

tirzepatide

endocrine society clinical practice

low testosterone

hypogonadism and metabolic syndrome

testosterone replacement therapy

metabolic regulation

receptor agonists

hypogonadism

hpg axis

insulin sensitivity